In mathematics, a cardinal number, or cardinal for short, is what is commonly called the number of elements of a set. In the case of a finite set, its cardinal number, or cardinality is therefore a natural number. For dealing with the case of infinite sets, the infinite cardinal numbers have been introduced, which are often denoted with the Hebrew letter (aleph) marked with subscript indicating their rank among the infinite cardinals.

Cardinality is defined in terms of bijective functions. Two sets have the same cardinality if, and only if, there is a one-to-one correspondence (bijection) between the elements of the two sets. In the case of finite sets, this agrees with the intuitive notion of number of elements. In the case of infinite sets, the behavior is more complex. A fundamental theorem due to Georg Cantor shows that it is possible for infinite sets to have different cardinalities, and in particular the cardinality of the set of real numbers is greater than the cardinality of the set of natural numbers. It is also possible for a proper subset of an infinite set to have the same cardinality as the original set—something that cannot happen with proper subsets of finite sets.

There is a transfinite sequence of cardinal numbers:

This sequence starts with the natural numbers including zero (finite cardinals), which are followed by the aleph numbers. The aleph numbers are indexed by ordinal numbers. If the axiom of choice is true, this transfinite sequence includes every cardinal number. If the axiom of choice is not true (see Axiom of choice § Independence), there are infinite cardinals that are not aleph numbers.

Cardinality is studied for its own sake as part of set theory. It is also a tool used in branches of mathematics including model theory, combinatorics, abstract algebra and mathematical analysis. In category theory, the cardinal numbers form a skeleton of the category of sets.

History

editThe notion of cardinality, as now understood, was formulated by Georg Cantor, the originator of set theory, in 1874–1884. Cardinality can be used to compare an aspect of finite sets. For example, the sets {1,2,3} and {4,5,6} are not equal, but have the same cardinality, namely three. This is established by the existence of a bijection (i.e., a one-to-one correspondence) between the two sets, such as the correspondence {1→4, 2→5, 3→6}.

Cantor applied his concept of bijection to infinite sets[1] (for example the set of natural numbers N = {0, 1, 2, 3, ...}). Thus, he called all sets having a bijection with N denumerable (countably infinite) sets, which all share the same cardinal number. This cardinal number is called , aleph-null. He called the cardinal numbers of infinite sets transfinite cardinal numbers.

Cantor proved that any unbounded subset of N has the same cardinality as N, even though this might appear to run contrary to intuition. He also proved that the set of all ordered pairs of natural numbers is denumerable; this implies that the set of all rational numbers is also denumerable, since every rational can be represented by a pair of integers. He later proved that the set of all real algebraic numbers is also denumerable. Each real algebraic number z may be encoded as a finite sequence of integers, which are the coefficients in the polynomial equation of which it is a solution, i.e. the ordered n-tuple (a0, a1, ..., an), ai ∈ Z together with a pair of rationals (b0, b1) such that z is the unique root of the polynomial with coefficients (a0, a1, ..., an) that lies in the interval (b0, b1).

In his 1874 paper "On a Property of the Collection of All Real Algebraic Numbers", Cantor proved that there exist higher-order cardinal numbers, by showing that the set of real numbers has cardinality greater than that of N. His proof used an argument with nested intervals, but in an 1891 paper, he proved the same result using his ingenious and much simpler diagonal argument. The new cardinal number of the set of real numbers is called the cardinality of the continuum and Cantor used the symbol for it.

Cantor also developed a large portion of the general theory of cardinal numbers; he proved that there is a smallest transfinite cardinal number ( , aleph-null), and that for every cardinal number there is a next-larger cardinal

His continuum hypothesis is the proposition that the cardinality of the set of real numbers is the same as . This hypothesis is independent of the standard axioms of mathematical set theory, that is, it can neither be proved nor disproved from them. This was shown in 1963 by Paul Cohen, complementing earlier work by Kurt Gödel in 1940.

Motivation

editIn informal use, a cardinal number is what is normally referred to as a counting number, provided that 0 is included: 0, 1, 2, .... They may be identified with the natural numbers beginning with 0. The counting numbers are exactly what can be defined formally as the finite cardinal numbers. Infinite cardinals only occur in higher-level mathematics and logic.

More formally, a non-zero number can be used for two purposes: to describe the size of a set, or to describe the position of an element in a sequence. For finite sets and sequences it is easy to see that these two notions coincide, since for every number describing a position in a sequence we can construct a set that has exactly the right size. For example, 3 describes the position of 'c' in the sequence <'a','b','c','d',...>, and we can construct the set {a,b,c}, which has 3 elements.

However, when dealing with infinite sets, it is essential to distinguish between the two, since the two notions are in fact different for infinite sets. Considering the position aspect leads to ordinal numbers, while the size aspect is generalized by the cardinal numbers described here.

The intuition behind the formal definition of cardinal is the construction of a notion of the relative size or "bigness" of a set, without reference to the kind of members which it has. For finite sets this is easy; one simply counts the number of elements a set has. In order to compare the sizes of larger sets, it is necessary to appeal to more refined notions.

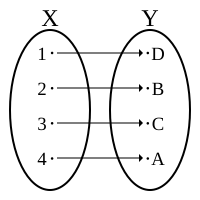

A set Y is at least as big as a set X if there is an injective mapping from the elements of X to the elements of Y. An injective mapping identifies each element of the set X with a unique element of the set Y. This is most easily understood by an example; suppose we have the sets X = {1,2,3} and Y = {a,b,c,d}, then using this notion of size, we would observe that there is a mapping:

- 1 → a

- 2 → b

- 3 → c

which is injective, and hence conclude that Y has cardinality greater than or equal to X. The element d has no element mapping to it, but this is permitted as we only require an injective mapping, and not necessarily a bijective mapping. The advantage of this notion is that it can be extended to infinite sets.

We can then extend this to an equality-style relation. Two sets X and Y are said to have the same cardinality if there exists a bijection between X and Y. By the Schroeder–Bernstein theorem, this is equivalent to there being both an injective mapping from X to Y, and an injective mapping from Y to X. We then write |X| = |Y|. The cardinal number of X itself is often defined as the least ordinal a with |a| = |X|.[2] This is called the von Neumann cardinal assignment; for this definition to make sense, it must be proved that every set has the same cardinality as some ordinal; this statement is the well-ordering principle. It is however possible to discuss the relative cardinality of sets without explicitly assigning names to objects.

The classic example used is that of the infinite hotel paradox, also called Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel. Supposing there is an innkeeper at a hotel with an infinite number of rooms. The hotel is full, and then a new guest arrives. It is possible to fit the extra guest in by asking the guest who was in room 1 to move to room 2, the guest in room 2 to move to room 3, and so on, leaving room 1 vacant. We can explicitly write a segment of this mapping:

- 1 → 2

- 2 → 3

- 3 → 4

- ...

- n → n + 1

- ...

With this assignment, we can see that the set {1,2,3,...} has the same cardinality as the set {2,3,4,...}, since a bijection between the first and the second has been shown. This motivates the definition of an infinite set being any set that has a proper subset of the same cardinality (i.e., a Dedekind-infinite set); in this case {2,3,4,...} is a proper subset of {1,2,3,...}.

When considering these large objects, one might also want to see if the notion of counting order coincides with that of cardinal defined above for these infinite sets. It happens that it does not; by considering the above example we can see that if some object "one greater than infinity" exists, then it must have the same cardinality as the infinite set we started out with. It is possible to use a different formal notion for number, called ordinals, based on the ideas of counting and considering each number in turn, and we discover that the notions of cardinality and ordinality are divergent once we move out of the finite numbers.

It can be proved that the cardinality of the real numbers is greater than that of the natural numbers just described. This can be visualized using Cantor's diagonal argument; classic questions of cardinality (for instance the continuum hypothesis) are concerned with discovering whether there is some cardinal between some pair of other infinite cardinals. In more recent times, mathematicians have been describing the properties of larger and larger cardinals.

Since cardinality is such a common concept in mathematics, a variety of names are in use. Sameness of cardinality is sometimes referred to as equipotence, equipollence, or equinumerosity. It is thus said that two sets with the same cardinality are, respectively, equipotent, equipollent, or equinumerous.

Formal definition

editFormally, assuming the axiom of choice, the cardinality of a set X is the least ordinal number α such that there is a bijection between X and α. This definition is known as the von Neumann cardinal assignment. If the axiom of choice is not assumed, then a different approach is needed. The oldest definition of the cardinality of a set X (implicit in Cantor and explicit in Frege and Principia Mathematica) is as the class [X] of all sets that are equinumerous with X. This does not work in ZFC or other related systems of axiomatic set theory because if X is non-empty, this collection is too large to be a set. In fact, for X ≠ ∅ there is an injection from the universe into [X] by mapping a set m to {m} × X, and so by the axiom of limitation of size, [X] is a proper class. The definition does work however in type theory and in New Foundations and related systems. However, if we restrict from this class to those equinumerous with X that have the least rank, then it will work (this is a trick due to Dana Scott:[3] it works because the collection of objects with any given rank is a set).

Von Neumann cardinal assignment implies that the cardinal number of a finite set is the common ordinal number of all possible well-orderings of that set, and cardinal and ordinal arithmetic (addition, multiplication, power, proper subtraction) then give the same answers for finite numbers. However, they differ for infinite numbers. For example, in ordinal arithmetic while in cardinal arithmetic, although the von Neumann assignment puts . On the other hand, Scott's trick implies that the cardinal number 0 is , which is also the ordinal number 1, and this may be confusing. A possible compromise (to take advantage of the alignment in finite arithmetic while avoiding reliance on the axiom of choice and confusion in infinite arithmetic) is to apply von Neumann assignment to the cardinal numbers of finite sets (those which can be well ordered and are not equipotent to proper subsets) and to use Scott's trick for the cardinal numbers of other sets.

Formally, the order among cardinal numbers is defined as follows: |X| ≤ |Y| means that there exists an injective function from X to Y. The Cantor–Bernstein–Schroeder theorem states that if |X| ≤ |Y| and |Y| ≤ |X| then |X| = |Y|. The axiom of choice is equivalent to the statement that given two sets X and Y, either |X| ≤ |Y| or |Y| ≤ |X|.[4][5]

A set X is Dedekind-infinite if there exists a proper subset Y of X with |X| = |Y|, and Dedekind-finite if such a subset does not exist. The finite cardinals are just the natural numbers, in the sense that a set X is finite if and only if |X| = |n| = n for some natural number n. Any other set is infinite.

Assuming the axiom of choice, it can be proved that the Dedekind notions correspond to the standard ones. It can also be proved that the cardinal (aleph null or aleph-0, where aleph is the first letter in the Hebrew alphabet, represented ) of the set of natural numbers is the smallest infinite cardinal (i.e., any infinite set has a subset of cardinality ). The next larger cardinal is denoted by , and so on. For every ordinal α, there is a cardinal number and this list exhausts all infinite cardinal numbers.

Cardinal arithmetic

editWe can define arithmetic operations on cardinal numbers that generalize the ordinary operations for natural numbers. It can be shown that for finite cardinals, these operations coincide with the usual operations for natural numbers. Furthermore, these operations share many properties with ordinary arithmetic.

Successor cardinal

editIf the axiom of choice holds, then every cardinal κ has a successor, denoted κ+, where κ+ > κ and there are no cardinals between κ and its successor. (Without the axiom of choice, using Hartogs' theorem, it can be shown that for any cardinal number κ, there is a minimal cardinal κ+ such that ) For finite cardinals, the successor is simply κ + 1. For infinite cardinals, the successor cardinal differs from the successor ordinal.

Cardinal addition

editIf X and Y are disjoint, addition is given by the union of X and Y. If the two sets are not already disjoint, then they can be replaced by disjoint sets of the same cardinality (e.g., replace X by X×{0} and Y by Y×{1}).

Zero is an additive identity κ + 0 = 0 + κ = κ.

Addition is associative (κ + μ) + ν = κ + (μ + ν).

Addition is commutative κ + μ = μ + κ.

Addition is non-decreasing in both arguments:

Assuming the axiom of choice, addition of infinite cardinal numbers is easy. If either κ or μ is infinite, then

Subtraction

editAssuming the axiom of choice and, given an infinite cardinal σ and a cardinal μ, there exists a cardinal κ such that μ + κ = σ if and only if μ ≤ σ. It will be unique (and equal to σ) if and only if μ < σ.

Cardinal multiplication

editThe product of cardinals comes from the Cartesian product.

κ·0 = 0·κ = 0.

κ·μ = 0 → (κ = 0 or μ = 0).

One is a multiplicative identity κ·1 = 1·κ = κ.

Multiplication is associative (κ·μ)·ν = κ·(μ·ν).

Multiplication is commutative κ·μ = μ·κ.

Multiplication is non-decreasing in both arguments: κ ≤ μ → (κ·ν ≤ μ·ν and ν·κ ≤ ν·μ).

Multiplication distributes over addition: κ·(μ + ν) = κ·μ + κ·ν and (μ + ν)·κ = μ·κ + ν·κ.

Assuming the axiom of choice, multiplication of infinite cardinal numbers is also easy. If either κ or μ is infinite and both are non-zero, then

Division

editAssuming the axiom of choice and, given an infinite cardinal π and a non-zero cardinal μ, there exists a cardinal κ such that μ · κ = π if and only if μ ≤ π. It will be unique (and equal to π) if and only if μ < π.

Cardinal exponentiation

editExponentiation is given by

where XY is the set of all functions from Y to X.[6] It is easy to check that the right-hand side depends only on and .

- κ0 = 1 (in particular 00 = 1), see empty function.

- If 1 ≤ μ, then 0μ = 0.

- 1μ = 1.

- κ1 = κ.

- κμ + ν = κμ·κν.

- κμ · ν = (κμ)ν.

- (κ·μ)ν = κν·μν.

Exponentiation is non-decreasing in both arguments:

- (1 ≤ ν and κ ≤ μ) → (νκ ≤ νμ) and

- (κ ≤ μ) → (κν ≤ μν).

2|X| is the cardinality of the power set of the set X and Cantor's diagonal argument shows that 2|X| > |X| for any set X. This proves that no largest cardinal exists (because for any cardinal κ, we can always find a larger cardinal 2κ). In fact, the class of cardinals is a proper class. (This proof fails in some set theories, notably New Foundations.)

All the remaining propositions in this section assume the axiom of choice:

- If κ and μ are both finite and greater than 1, and ν is infinite, then κν = μν.

- If κ is infinite and μ is finite and non-zero, then κμ = κ.

If 2 ≤ κ and 1 ≤ μ and at least one of them is infinite, then:

- Max (κ, 2μ) ≤ κμ ≤ Max (2κ, 2μ).

Using König's theorem, one can prove κ < κcf(κ) and κ < cf(2κ) for any infinite cardinal κ, where cf(κ) is the cofinality of κ.

Roots

editAssuming the axiom of choice and, given an infinite cardinal κ and a finite cardinal μ greater than 0, the cardinal ν satisfying will be .

Logarithms

editAssuming the axiom of choice and, given an infinite cardinal κ and a finite cardinal μ greater than 1, there may or may not be a cardinal λ satisfying . However, if such a cardinal exists, it is infinite and less than κ, and any finite cardinality ν greater than 1 will also satisfy .

The logarithm of an infinite cardinal number κ is defined as the least cardinal number μ such that κ ≤ 2μ. Logarithms of infinite cardinals are useful in some fields of mathematics, for example in the study of cardinal invariants of topological spaces, though they lack some of the properties that logarithms of positive real numbers possess.[7][8][9]

The continuum hypothesis

editThe continuum hypothesis (CH) states that there are no cardinals strictly between and The latter cardinal number is also often denoted by ; it is the cardinality of the continuum (the set of real numbers). In this case

Similarly, the generalized continuum hypothesis (GCH) states that for every infinite cardinal , there are no cardinals strictly between and . Both the continuum hypothesis and the generalized continuum hypothesis have been proved to be independent of the usual axioms of set theory, the Zermelo–Fraenkel axioms together with the axiom of choice (ZFC).

Indeed, Easton's theorem shows that, for regular cardinals , the only restrictions ZFC places on the cardinality of are that , and that the exponential function is non-decreasing.

See also

editReferences

editNotes

- ^ Dauben 1990, pg. 54

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Cardinal Number". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- ^ Deiser, Oliver (May 2010). "On the Development of the Notion of a Cardinal Number". History and Philosophy of Logic. 31 (2): 123–143. doi:10.1080/01445340903545904. S2CID 171037224.

- ^ Enderton, Herbert. "Elements of Set Theory", Academic Press Inc., 1977. ISBN 0-12-238440-7

- ^ Friedrich M. Hartogs (1915), Felix Klein; Walther von Dyck; David Hilbert; Otto Blumenthal (eds.), "Über das Problem der Wohlordnung", Math. Ann., Bd. 76 (4), Leipzig: B. G. Teubner: 438–443, doi:10.1007/bf01458215, ISSN 0025-5831, S2CID 121598654, archived from the original on 2016-04-16, retrieved 2014-02-02

- ^ a b c Schindler 2014, pg. 34

- ^ Robert A. McCoy and Ibula Ntantu, Topological Properties of Spaces of Continuous Functions, Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1315, Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Eduard Čech, Topological Spaces, revised by Zdenek Frolík and Miroslav Katetov, John Wiley & Sons, 1966.

- ^ D. A. Vladimirov, Boolean Algebras in Analysis, Mathematics and Its Applications, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bibliography

- Dauben, Joseph Warren (1990), Georg Cantor: His Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691-02447-2

- Hahn, Hans, Infinity, Part IX, Chapter 2, Volume 3 of The World of Mathematics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956.

- Halmos, Paul, Naive set theory. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1960. Reprinted by Springer-Verlag, New York, 1974. ISBN 0-387-90092-6 (Springer-Verlag edition).

- Schindler, Ralf-Dieter (2014). Set theory : exploring independence and truth. Universitext. Cham: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-06725-4. ISBN 978-3-319-06725-4.

External links

edit- "Cardinal number", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]