Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam.

Pre-Islamic Arabia شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام (Arabic) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

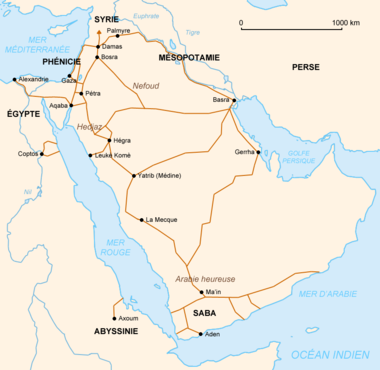

Nabataean trade routes in Pre-Islamic Arabia | |||||||

| |||||||

Pre-Islamic Arabia included both nomadic and settled populations. Several settled populations developed distinctive civilizations. From around the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE, Southern Arabia was the home to a number of kingdoms, such as the Sabaeans and the Minaeans, and Eastern Arabia was inhabited by Semitic-speaking peoples who presumably migrated from the southwest, such as the so-called Samad population.[1] From 106 CE to 630 CE, Arabia's most northwestern areas were controlled by the Roman Empire, which governed it as Arabia Petraea.[2] A few nodal points were controlled by the Iranian peoples, first under the Parthians and then under the Sasanians.

Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia was diverse; although polytheism was prevalent for most of its history (especially in forms related to ancient Semitic religions), monotheism came to dominate in the region in the centuries leading up to the origins of Islam. There were also large pre-Islamic Christian and Jewish communities, especially in the north and south. More speculatively, Iranian religions may have played a role as well.[3]

Sources

editDetailed literary accounts from within pre-Islamic Arabia are absent. "There is no Arabian Tacitus or Josephus to furnish us with a grand narrative."[4] Information has to be pieced together from a variety of sources, all of them suffering from issues that may include incompleteness, lateness, or bias. One type of later source are accounts whose traditions were collected and codified during the Islamic period. This includes the Quran, Arab oral traditions, and collections of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. Contemporary sources from pre-Islamic Arabia mainly include pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions and other information that can be discovered from archaeological excavations, plus literary accounts from observers beyond the peninsula, specifically in works composed by Assyrians, Babylonians, Israelites, Greeks, Romans, and Persians.[5][6] Because large-scale excavations in the region have only recently begun, no firm chronology has yet been established for the material evidence coming out of the region.[7]

The earliest documentation in written sources of any region of Arabia is from 2500 BCE, of Eastern Arabia. The earliest written documentation of North and South Arabia is from 900 BCE.[8]

Eastern Arabia

editEastern Arabia is a geographic region that generally refers to the territories covered by modern-day Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the east coast of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman.[8] The main language in this region among sedentary peoples was Aramaic, Arabic, and to some degree, Persian. The Syriac language also came to be spoken as a liturgical language.[9]

Many religions were practiced in the area. Practitioners included Arab Christians (including the tribe of Abd al-Qays), Aramean Christians, Persian-speaking Zoroastrians[10] and Jewish agriculturalists.[11] One hypothesis holds that the contemporary Baharna are descendants of Arameans, Jews, and Persians from the area.[11][12] Zoroastrianism was also present in Eastern Arabia.[13][14][15] The Zoroastrians of Eastern Arabia were known as "Majoos" in pre-Islamic times.[16] The sedentary dialects of Eastern Arabia, including Bahrani Arabic, were influenced by Akkadian, Aramaic and Syriac languages.[17][18]

Dilmun

editDilmun is the earliest recorded civilization from Eastern Arabia, mentioned in written records in the 3rd millennium BCE,[19] with archaeological evidence indicating activity from the fourth to first millennia BCE, its importance faltering after 1800.[20][21] Dilmun is regarded as one of the oldest ancient civilizations in the Middle East in general.[22][23]

The land of Dilmun covered modern-day Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the adjacent coast of Saudi Arabia. Its capital was located in Bahrain. The Dilmun civilization was an important trading center[20] which at the height of its power controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[20] This was enabled by a number of natural advantages to the region, and part of this was its abundant underground water supplies and easy anchorages for ships. It became a center for long-distance trade and all types of commodities passed through it (trade extending to areas as far as the Indus Valley[23]), including a variety of exotic goods. As a result, Dilmun became legendary in Mesopotamian literature.[19] The Sumerians regarded Dilmun as holy land.[24] The Sumerians described Dilmun as a paradise garden in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[25] The Sumerian tale of the garden paradise of Dilmun may have been an inspiration for the Garden of Eden story.[25] Dilmun, sometimes described as "the place where the sun rises" and "the Land of the Living", is the scene of some versions of the Eridu Genesis, and the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim (Ziusudra), was taken by the gods to live forever. Thorkild Jacobsen's translation of the Eridu Genesis calls it "Mount Dilmun" which he locates as a "faraway, half-mythical place".[26]

Dilmun was mentioned in two letters dated to the reign of Burna-Buriash II (c. 1370 BCE) recovered from Nippur, during the Kassite dynasty of Babylon. These letters were from a provincial official, Ilī-ippašra, in Dilmun to his friend Enlil-kidinni in Mesopotamia. The names referred to are Akkadian. These letters and other documents, hint at an administrative relationship between Dilmun and Babylon at that time. Following the collapse of the Kassite dynasty, Mesopotamian documents make no mention of Dilmun with the exception of Assyrian inscriptions dated to 1250 BCE which proclaimed the Assyrian king to be king of Dilmun and Meluhha. Assyrian inscriptions recorded tribute from Dilmun. There are other Assyrian inscriptions during the first millennium BCE indicating Assyrian sovereignty over Dilmun.[27] Dilmun was also later on controlled by the Kassite dynasty in Mesopotamia.[28]

In 19th and early 20th centuries, some historians believed that the Phoenicians originated from Eastern Arabia, particularly Dilmun. However, this theory has since been abandoned.[29]

Gerrha

editGerrha was an ancient city of Eastern Arabia, on the west side of the Persian Gulf. Soon after the conquests of Alexander the Great, it became the most important center of trader for the Hellenistic world in the Gulf region, known for its transport of Arabian aromatics and goods from India further away. It retained its prominence until the first centuries of the common era.[30] While there is no certainty as to which archaeological site the Gerrha of Greek sources can be identified with, the most prominent candidates have been Thaj and Hagar (modern-day Hofuf).[31]

Bahrain (Tylos)

editBahrain was referred to by the Greeks as Tylos, the center of pearl trading, when Nearchus came to discover it serving under Alexander the Great.[32] From the 6th to 3rd century BCE Bahrain was included in Persian Empire by Achaemenians, an Iranian dynasty.[33] The Greek admiral Nearchus is believed to have been the first of Alexander's commanders to visit this islands, and he found a verdant land that was part of a wide trading network; he recorded: "That in the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton tree, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, a very different degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive. The use of these is not confined to India, but extends to Arabia."[34] The Greek historian, Theophrastus, states that much of the islands were covered in these cotton trees and that Tylos was famous for exporting walking canes engraved with emblems that were customarily carried in Babylon.[35] Ares was also worshipped by the ancient Baharna and the Greek empires.[36]

It is not known whether Bahrain was part of the Seleucid Empire, although the archaeological site at Qalat Al Bahrain has been proposed as a Seleucid base in the Persian Gulf.[37] Alexander had planned to settle the eastern shores of the Persian Gulf with Greek empires, and although it is not clear that this happened on the scale he envisaged, Tylos was very much part of the Hellenised world: the language of the upper classes was Greek (although Aramaic was in everyday use), while Zeus was worshipped in the form of the Arabian sun-god Shams.[38] Tylos even became the site of Greek athletic contests.[39]

Beth Qatraye

editIn antiquity, Syriac Christians referred to a region in northeast Arabia as Beth Qatraye, or the "region of the Qataris". This region encompassed a territory that, today, includes Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, Al-Hasa, Qatar, and possibly the United Arab Emirates.[40] The region was also sometimes called "the Isles".[41]

By the 5th century, Beth Qatraye was a major centre for Nestorian Christianity, which had come to dominate the southern shores of the Persian Gulf.[42][43] As a sect, the Nestorians were often persecuted as heretics by the Byzantine Empire, but eastern Arabia was outside the Empire's control offering some safety. Several notable Nestorian writers originated from Beth Qatraye, including Isaac of Nineveh, Dadisho Qatraya, Gabriel of Qatar and Ahob of Qatar.[42][44] Christianity's significance was diminished by the arrival of Islam in Eastern Arabia by 628.[45] In 676, the bishops of Beth Qatraye stopped attending synods; although the practice of Christianity persisted in the region until the late 9th century.[42]

The dioceses of Beth Qatraye did not form an ecclesiastical province, except for a short period during the mid-to-late seventh century.[42] They were instead subject to the Metropolitan of Fars.

Beth Mazunaye

editOman and the United Arab Emirates comprised the ecclesiastical province known as Beth Mazunaye. The name was derived from 'Mazun', the Persian name for Oman and the United Arab Emirates.[41]

Persian Empires

editFrom the founding of the Parthian Empire in the 3rd century BCE, to the dissolution of the Sasanian Empire in the 7th century CE, Persian dynasties exerted significant political and, at times, territorial control and influence over Eastern Arabia.

After the death of Alexander the Great, the Seleucid Empire was carved out in a region of West Asia and was a major entity on the border of Eastern Arabia. By about 250 BCE, the Seleucids had lost the territory they held adjacent to Arabia to Parthia, an Iranian tribe from Central Asia. Parthian influence extended over the Persian Gulf and reached as far as Oman. Garrisons were established at the southern coast of the Gulf to help extend their power.[46]

In the 3rd century CE, the Sasanians succeeded the Parthians and held the area until the rise of Islam four centuries later.[46] Ardashir I, the first ruler of this dynasty marched down the Persian Gulf to Oman and Bahrain and defeated Sanatruq [47] (or Satiran[33]), probably the Parthian governor of Eastern Arabia.[48] He appointed his son Shapur I as governor of Eastern Arabia. Shapur constructed a new city there and named it Batan Ardashir after his father.[33] At this time, Eastern Arabia incorporated the southern Sasanian province covering the Persian Gulf's southern shore plus the archipelago of Bahrain.[48] The southern province of the Sasanians was subdivided into three districts of Haggar (Hofuf, Saudi Arabia), Batan Ardashir (al-Qatif province, Saudi Arabia), and Mishmahig (Muharraq, Bahrain; also referred to as Samahij)[33] (In Middle-Persian/Pahlavi means "ewe-fish".[49]) which included the Bahrain archipelago that was earlier called Aval.[33][48] The name, meaning 'ewe-fish' would appear to suggest that the name /Tulos/ is related to Hebrew /ṭāleh/ 'lamb' (Strong's 2924).[50]

South Arabia

editSouth Arabia roughly corresponds to modern-day Yemen, with Oman being designated as part of Eastern Arabia.[8] The earliest kingdoms from the area known today emerged in the late second millennium BCE, and these included the Kingdom of Ma'in, Saba, Hadhramaut, Aswan, and Qataban. In the third century CE, the Kingdom of Himyar emerged and conquered its neighbours to exert complete political domination over South Arabia. This situation persisted for several centuries, until the Himyarite polity unravelled over the course of the sixth century CE and experienced a societal collapse. The exact cause is not definitively known, but there is evidence that a group of coinciding events helped bring this situation about. Epidemically, an inscription from the 550s about an epidemic indicates that the Plague of Justinian struck the area. Militarily, the Aksumite invasion of Himyar fragmented contributed to the fragmentation of existing political structures. Severe climactic changes are also known from this time. These included the abrupt appearance of severe droughts from about 500 to 530 CE, and the appearance of the Late Antique Little Ice Age in the years approaching the mid-6th century. Different regions of Arabia were impacted in different ways, but the bulk of the effect was in the South, and there, especially the Southwest. By the 550s and 560s, Himyar's decline was completed, as it faced military incursions from Central and Northwest Arabia, as well as insurrections from home. In 559 CE, the final Himyarite inscription was recorded. The collapse of the traditional order is indicated by the breakdown of the Marib Dam over the course of the 570s. A creeping in of influence from the Persian Sasanian Empire is evident towards the end of the 6th century.[51][52]

Kingdom of Ma'in (10th century BCE – 150 BCE)

editDuring Minaean rule, the capital was at Karna (now known as Sa'dah). Their other important city was Yathill (now known as Baraqish). The Minaean Kingdom was centered in northwestern Yemen, with most of its cities lying along Wādī Madhab. Minaean inscriptions have been found far afield of the Kingdom of Maīin, as far away as al-'Ula in northwestern Saudi Arabia and even on the island of Delos and Egypt. It was the first of the Yemeni kingdoms to end, and the Minaean language died around 100 CE .[53][54][55]

Kingdom of Saba (1200 BCE – 275 CE)

editDuring Sabaean rule, trade and agriculture flourished, generating much wealth and prosperity. The Sabaean kingdom was located in Yemen, and its capital, Ma'rib, is located near what is now Yemen's modern capital, Sana'a.[56] According to South Arabian tradition, the eldest son of Noah, Shem, founded the city of Ma'rib.[1]

During Sabaean rule, Yemen was called "Arabia Felix" by the Romans, who were impressed by its wealth and prosperity. The Roman emperor Augustus sent a military expedition to conquer the "Arabia Felix", under the command of Aelius Gallus. After an unsuccessful siege of Ma'rib, the Roman general retreated to Egypt, while his fleet destroyed the port of Aden in order to guarantee the Roman merchant route to India.

The success of the kingdom was based on the cultivation and trade of spices and aromatics including frankincense and myrrh. These were exported to the Mediterranean, India, and Abyssinia, where they were greatly prized by many cultures, using camels on routes through Arabia, and to India by sea.

During the 8th and 7th century BCE, there was a close contact of cultures between the Kingdom of Dʿmt in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia and Saba. Though the civilization was indigenous and the royal inscriptions were written in a sort of proto-Ethiosemitic, there were also some Sabaean immigrants in the kingdom as evidenced by a few of the Dʿmt inscriptions.[57][58]

Kingdom of Hadhramaut (8th century BCE – 3rd century CE)

editThe first known inscriptions of Hadramaut are known from the 8th century BCE. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Hadramaut, Yada`'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Hadramaut became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing Yemeni kingdom of Himyar toward the end of the 1st century BCE, but it was able to repel the attack. Hadramaut annexed Qataban in the second half of the 2nd century CE, reaching its greatest size. The kingdom of Hadramaut was eventually conquered by the Himyarite king Shammar Yahri'sh around 300 CE, unifying all of the South Arabian kingdoms.[59]

Kingdom of Awsan (8th century BCE – 6th century BCE)

editThe ancient Kingdom of Awsan in South Arabia (modern Yemen), with a capital at Ḥagar Yaḥirr in the wadi Markhah, to the south of the Wādī Bayḥān, is now marked by a tell or artificial mound, which is locally named Ḥajar Asfal.

Kingdom of Qataban (4th century BCE – 3rd century CE)

editQataban was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms which thrived in the Beihan valley. Like the other Southern Arabian kingdoms, it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense, which were burned at altars. The capital of Qataban was named Timna and was located on the trade route which passed through the other kingdoms of Hadramaut, Saba and Ma'in. The chief deity of the Qatabanians was Amm, or "Uncle" and the people called themselves the "children of Amm".

Kingdom of Himyar (late 2nd century BCE – 525 CE)

editThe Himyarites rebelled against Qataban and eventually united Southwestern Arabia (Hejaz and Yemen), controlling the Red Sea as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. From their capital city, Ẓafār, the Himyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east as eastern Yemen and as far north as Najran[60] Together with their Kindite allies, it extended maximally as far north as Riyadh and as far east as Yabrin.

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. Gadarat (GDRT) of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba, and a Himyarite text notes that Hadramaut and Qataban were also allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Aksumite Empire was able to capture the Himyarite capital of Thifar in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha`ir Awtar of Saba unexpectedly turned on Hadramaut, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Himyar then allied with Saba and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Thifar, which had been under the control of Gadarat's son Beygat, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihama.[61][62] The standing relief image of a crowned man, is taken to be a representation possibly of the Jewish king Malkīkarib Yuhaʾmin or more likely the Christian Esimiphaios (Samu Yafa').[63]

Aksumite occupation of Yemen (525 – 570 CE)

editThe Aksumite intervention is connected with Dhu Nuwas, a Himyarite king who changed the state religion to Judaism and began to persecute the Christians in Yemen. Outraged, Kaleb, the Christian King of Aksum with the encouragement of the Byzantine Emperor Justin I invaded and annexed Yemen. The Aksumites controlled Himyar and attempted to invade Mecca in the year 570 CE. Eastern Yemen remained allied to the Sasanians via tribal alliances with the Lakhmids, which later brought the Sasanian army into Yemen, ending the Aksumite period.

Sasanian period (570 – 630 CE)

editThe Persian king Khosrau I sent troops under the command of Vahriz (Persian: اسپهبد وهرز), who helped the semi-legendary Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan to drive the Aksumites out of Yemen. Southern Arabia became a Persian dominion under a Yemenite vassal and thus came within the sphere of influence of the Sasanian Empire. After the demise of the Lakhmids, another army was sent to Yemen, making it a province of the Sasanian Empire under a Persian satrap. Following the death of Khosrau II in 628, the Persian governor in Southern Arabia, Badhan, converted to Islam and Yemen followed the new religion.

Western Arabia (Hejaz)

editKingdom of Lihyan/Dedan (5th century BCE - 1st century BCE)

editLihyan, also called Dadān or Dedan, was a powerful and highly organized ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language. Significant controversy exists concerning the range of the existence of this civilization, with estimates as early as the 5th century BCE for when it was founded, and estimates as late as the 1st century BCE for when it ended. The cause of its end is unclear: it has been proposed either that the Nabataeans annexed the area in the 1st century BCE, or that the area declined for other causes in this time, with the Nabataeans annexing the place in the face of a power vacuum in the succeeding century.[64]

Thamud

editThe Thamud (Arabic: ثمود) was an ancient civilization in Hejaz, documented in sources from the eighth century BCE until the fifth century CE. They are attested in contemporaneous Mesopotamian and Classical, and Arabic inscriptions from the eighth century BCE, all the way until the fifth century CE, when they served as Roman auxiliaries. They are also later remembered in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry and Islamic-era sources, including the Quran. Prominently, they appear in the Ruwafa inscriptions discovered in a temple constructed circa 165–169 CE in honor of the local deity, ʾlhʾ.

Thamud appears twenty-six times in the Quran where the tribe is presented as an example of an ancient polytheistic people destroyed by God for their rejection of God's prophet Salih.[65] Thamud is associated in the Quran into its grander history of a pattern of rebellion and destruction of past groups of people. This is done the most times with Ad, but others as well like Lot and Noah. When Salih calls Thamud to serve one God, they demand a sign from him. He presents them with a miraculous she-camel. Thamud, unconvincing, injures the camel: for this God destroys them, except Salih and his followers. This account is embellished with a more detailed background in the Islamic exegetical tradition. Some traditions locate them in northwestern Arabia at Hegra and in others they are identified as Nabataeans.[66] Islamic genealogy describes the Thamud as among the true Arab tribes, as opposed to the "Arabicized Arabs".[67]

North Arabia

editKingdom of Qedar (8th century BCE – ?)

editThe most organized of the Northern Arabian tribes, at the height of their rule in the 6th century BCE, the Kingdom of Qedar spanned a large area between the Persian Gulf and the Sinai.[69] An influential force between the 8th and 4th centuries BCE, Qedarite monarchs are first mentioned in inscriptions from the Assyrian Empire. Some early Qedarite rulers were vassals of that empire, with revolts against Assyria becoming more common in the 7th century BCE. It is thought that the Qedarites were eventually subsumed into the Nabataean state after their rise to prominence in the 2nd century CE.

The Achaemenids in Northern Arabia

editAchaemenid Arabia corresponded to the lands between Nile Delta (Egypt) and Mesopotamia, later known to Romans as Arabia Petraea. According to Herodotus, Cambyses did not subdue the Arabs when he attacked Egypt in 525 BCE. His successor Darius the Great does not mention the Arabs in the Behistun inscription from the first years of his reign, but does mention them in later texts. This suggests that Darius might have conquered this part of Arabia[70] or that it was originally part of another province, perhaps Achaemenid Babylonia, but later became its own province.

Arabs were not considered as subjects to the Achaemenids, as other peoples were, and were exempt from taxation. Instead, they simply provided 1,000 talents of frankincense a year. They participated in the Second Persian invasion of Greece (479-480 BCE) while also helping the Achaemenids invade Egypt by providing water skins to the troops crossing the desert.[71]

Nabateans

editThe Nabataeans are not to be found among the tribes that are listed in Arab genealogies because the Nabatean kingdom ended a long time before the coming of Islam. They settled east of the Syro-African rift between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea, that is, in the land that had once been Edom. And although the first sure reference to them dates from 312 BCE, it is possible that they were present much earlier.

Petra (from the Greek petra, meaning 'of rock') lies in the Jordan Rift Valley, east of Wadi `Araba in Jordan about 80 km (50 mi) south of the Dead Sea. It came into prominence in the late 1st century BCE through the success of the spice trade. The city was the principal city of ancient Nabataea and was famous above all for two things: its trade and its hydraulic engineering systems. It was locally autonomous until the reign of Trajan, but it flourished under Roman rule. The town grew up around its Colonnaded Street in the 1st century and by the middle of the 1st century had witnessed rapid urbanization. The quarries were probably opened in this period, and there followed virtually continuous building through the 1st and 2nd centuries CE.

Roman Arabia

editThere is evidence of Roman rule in northern Arabia dating to the reign of Caesar Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE). During the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE), the already wealthy and elegant north Arabian city of Palmyra, located along the caravan routes linking Persia with the Mediterranean ports of Roman Syria and Phoenicia, was made part of the Roman province of Syria. The area steadily grew further in importance as a trade route linking Persia, India, China, and the Roman Empire. During the following period of great prosperity, the Arab citizens of Palmyra adopted customs and modes of dress from both the Iranian Parthian world to the east and the Graeco-Roman west. In 129, Hadrian visited the city and was so enthralled by it that he proclaimed it a free city and renamed it Palmyra Hadriana.

The Roman province of Arabia Petraea was created at the beginning of the 2nd century by emperor Trajan. It was centered on Petra, but included even areas of northern Arabia under Nabatean control.

Recently evidence has been discovered that Roman legions occupied Mada'in Saleh in the Hijaz mountains area of northwestern Arabia, increasing the extension of the "Arabia Petraea" province.[72]

The desert frontier of Arabia Petraea was called by the Romans the Limes Arabicus. As a frontier province, it included a desert area of northeastern Arabia populated by the nomadic Saraceni.

Later polities

editCentral Arabia

editKingdom of Kindah

editKindah was an Arab kingdom by the Kindah tribe, the tribe's existence dates back to the second century BCE.[73] The Kindites established a kingdom in Najd in central Arabia unlike the organized states of Yemen; its kings exercised an influence over a number of associated tribes more by personal prestige than by coercive settled authority. Their first capital was Qaryat Dhāt Kāhil, today known as Qaryat Al-Fāw.[74]

The Kindites were polytheistic until the 6th century CE, with evidence of rituals dedicated to the idols Athtar and Kāhil found in their ancient capital in south-central Arabia (present day Saudi Arabia). It is not clear whether they converted to Judaism or remained pagan, but there is a strong archaeological evidence that they were among the tribes in Dhū Nuwās' forces during the Jewish king's attempt to suppress Christianity in Yemen.[75] They converted to Islam in mid 7th century CE and played a crucial role during the Arab conquest of their surroundings, although some sub-tribes declared apostasy during the ridda after the death of Muḥammad.

Ancient South Arabian inscriptions mention a tribe settling in Najd called kdt, who had a king called rbˁt (Rabi'ah) from ḏw ṯwr-m (the people of Thawr), who had sworn allegiance to the king of Saba' and Dhū Raydān.[76] Since later Arab genealogists trace Kindah back to a person called Thawr ibn 'Uqayr, modern historians have concluded that this rbˁt ḏw ṯwrm (Rabī'ah of the People of Thawr) must have been a king of Kindah (kdt); the Musnad inscriptions mention that he was king both of kdt (Kindah) and qhtn (Qaḥṭān). They played a major role in the Himyarite-Ḥaḑramite war. Following the Himyarite victory, a branch of Kindah established themselves in the Marib region, while the majority of Kindah remained in their lands in central Arabia.

The first Classical author to mention Kindah was the Byzantine ambassador Nonnosos, who was sent by the Emperor Justinian to the area. He refers to the people in Greek as Khindynoi (Greek Χινδηνοι, Arabic Kindah), and mentions that they and the tribe of Maadynoi (Greek: Μααδηνοι, Arabic: Ma'ad) were the two most important tribes in the area in terms of territory and number. He calls the king of Kindah Kaïsos (Greek: Καισος, Arabic: Qays), the nephew of Aretha (Greek: Άρεθα, Arabic: Ḥārith).

Genealogical tradition

editArab traditions relating to the origins and classification of the Arabian tribes is based on biblical genealogy. The general consensus among 14th-century Arabic genealogists was that Arabs were three kinds:

- "Perishing Arabs": These are the ancients of whose history little is known. They include ʿĀd, Thamud, Tasm, Jadis, Imlaq and others. Jadis and Tasm perished because of genocide. ʿĀd and Thamud perished because of their decadence. Some people in the past doubted their existence, but Imlaq is the singular form of 'Amaleeq and is probably synonymous to the biblical Amalek.

- "Pure Arabs" (Qahtanite): These are traditionally considered to have originated from the progeny of Ya'rub bin Yashjub bin Qahtan so were also called Qahtanite Arabs.[77]

- "Arabized Arabs" (Adnanite): They are traditionally seen as having descended from Adnan.[77][78][79]

Modern historians believe that these distinctions were created during the Umayyad period, to support the cause of different political factions.[77]

Religion

editReligion in pre-Islamic Arabia included pre-Islamic Arabian polytheism, ancient Semitic religions, and Abrahamic religions such as Christianity and Judaism. Other religions that may have existed in pre-Islamic Arabia are Samaritanism, Mandaeism, and Iranian religions like Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism. Arabian polytheism was, according to Islamic tradition, the dominant form of religion in pre-Islamic Arabia, based on veneration of deities and spirits. Worship was directed to various gods and goddesses, including Hubal and the goddesses al-Lāt, Al-'Uzzá and Manāt, at local shrines and temples, maybe such as the Kaaba in Mecca. Deities were venerated and invoked through a variety of rituals, including pilgrimages and divination, as well as ritual sacrifice. Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in Meccan religion. Many of the physical descriptions of the pre-Islamic gods are traced to idols, especially near the Kaaba, which is said to have contained up to 360 of them in Islamic tradition.

Other religions were represented to varying, lesser degrees. The influence of the adjacent Roman and Aksumite resulted in Christian communities in the northwest, northeast and south of Arabia. Christianity in pre-Islamic Arabia made a lesser impact, but secured some conversions, in the remainder of the peninsula. With the exception of Nestorianism in the northeast and the Persian Gulf, the dominant form of Christianity was Miaphysitism. The peninsula had been a destination for Jewish migration since pre-Roman times, which had resulted in a diaspora community supplemented by local converts. Additionally, the influence of the Sasanian Empire resulted in Iranian religions being present in the peninsula. While Zoroastrianism existed in the eastern and southern Arabia, there was no existence of Manichaeism in Mecca.[80][81] From the fourth-century onwards, monotheism became increasingly prevalent in pre-Islamic Arabia, as is attested in texts like the inscriptions from Jabal Dabub, Ri al-Zallalah, and the Abd Shams inscription.[82]

Literacy

editAccording to a classification system for understanding literary in pre-Islamic Arabia established by Michael C.A. MacDonald, societies where writing is used can be divided into literate and non-literate societies, depending on the role that writing played within the functioning of the society. A nonliterate society is one where the ability to write is widespread without any place allocated for writing in the administration of a society (in the use of official inscriptions, legal contracts, etc). By contrast, a literate society relies on writing for the administrative functioning of a society.[83]

Literacy was widespread in pre-Islamic Arabia among both nomads and settled peoples. Nomadic Arab societies in northern Arabia and the southern Levant are classified as non-literate. This is because, while the capacity for writing was common among individuals in these populations, writing itself was primarily used for entertainment and passing the time as opposed to administrative or legal utility. South Arabia was a literate society, as indicated by the discovery of thousands of public inscriptions. The presence of thousands of graffiti also suggest that writing was widespread among the common people and not just the upper echelon. The major oases towns in North and West Arabia were also literate societies.[84][85]

Hellenization

editThere is evidence of Hellenization in pre-Islamic Arabia, including in parts of the Hejaz. Roman rule had long been imposed on Arabic-speaking populations in Syria, the Transjordan, Palestine, and the northern Hejaz (the Roman province of Arabia Petraea, established in 106 AD by the conquest of the Nabataean Kingdom).[86] Roman military encampments have been found at Hegra as well as in Ruwafa, reflected by a set of second-century Greek-Arabic bilingual inscriptions from northwestern Arabia known as the Ruwafa inscriptions.[87] More recent Latin inscriptions have revealed a Roman military presence as far south as the Farasan Islands, in southwestern Saudi Arabia.[88] At Qaryat al-Faw, capital of the ancient Kingdom of Kinda, statues of Greek deities such as Artemis, Heracles, and Harpocrates have been discovered. The Roman emperor is also mentioned repeatedly in Safaitic inscriptions. Arabic-speaking tribes were gradually converting to Christianity or becoming foederati of the emperor, resulting in increasing integration into the Roman world over time. In the mid-sixth century, for example, Justinian I was closely allied with the Ghassanids, a Hellenized Christian Arab kingdom.[86] The Letter of the Archimandrites dating to 569/570, composed in Greek but preserved in Syriac, demonstrates the presence and distribution of episcopal sees from its 137 Archimandrite signatories from the province of Roman Arabia.[89] Hellenization is also seen in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry.[90]

Art

editThe art is similar to that of neighbouring cultures. Pre-Islamic Yemen produced stylized alabaster (the most common material for sculpture) heads of great aesthetic and historic charm.

-

Votive alabaster figurines from Yemen that represent seated women and female heads; 3rd-1st century BC; National Museum of Oriental Art (Rome, Italy)

-

Stele, male wearing a baldric – an iconic artwork for pre-Islamic Arabia; 4th millennium BCE, Al-'Ula (Saudi Arabia); exhibition at the National Museum of Korea (Seoul)

-

Another anthropomorphic stele from pre-Islamic Saudi Arabia

-

South Arabian stele, bust of female raising her hand, with the donor's name, Rathadum, written below; 1st century BC-1st century AD; calcite-alabaster; 32.1 cm (12.6 in) x 23.3 cm (9.1 in) x 3.5 cm (1.3 in); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore).

-

Bas-relief with a palm tree; Sana'a, ancient Yemen, alabaster.

-

Miniature gate; Zafar, Yemen, 2rd-3rd century AD.

-

Pergamon Museum (Berlin). Exhibition "Roads of Arabia": Funeral mask and glove (1st century AD), gold, from Thaj, Tell Al-Zayer (National Museum, Riyadh)

-

Dhamar Ali Yahbur II, King of Himyarite

Late Antiquity

editThe early 7th century in Arabia began with the longest and most destructive period of the Byzantine–Sasanian Wars. It left both the Byzantine and Sasanian empires exhausted and susceptible to third-party attacks, particularly from nomadic Arabs united under a newly formed religion. According to historian George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Persian conflict opened the way for Islam".[91]

The demographic situation also favoured Arab expansion: overpopulation and lack of resources encouraged Arabs to migrate out of Arabia.[92]

Fall of the Empires

editBefore the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, the Plague of Justinian had erupted (541–542), spreading through Persia and into Byzantine territory. The Byzantine historian Procopius, who witnessed the plague, documented that citizens died at a rate of 10,000 per day in Constantinople.[93] The exact number; however, is often disputed by contemporary historians. Both empires were permanently weakened by the pandemic as their citizens struggled to deal with death as well as heavy taxation, which increased as each empire campaigned for more territory.

Despite almost succumbing to the plague, Byzantine emperor Justinian I (reigned 527–565) attempted to resurrect the might of the Roman Empire by expanding into Arabia. The Arabian Peninsula had a long coastline for merchant ships and an area of lush vegetation known as the Fertile Crescent which could help fund his expansion into Europe and North Africa. The drive into Persian territory would also put an end to tribute payments to the Sasanians, which resulted in an agreement to give 11,000 lb (5,000 kg) of tribute to the Persians annually in exchange for a ceasefire.[94]

However, Justinian could not afford further losses in Arabia. The Byzantines and the Sasanians sponsored powerful nomadic mercenaries from the desert with enough power to trump the possibility of aggression in Arabia. Justinian viewed his mercenaries as so valued for preventing conflict that he awarded their chief with the titles of patrician, phylarch, and king – the highest honours that he could bestow on anyone.[95] By the late 6th century, an uneasy peace remained until disagreements erupted between the mercenaries and their patron empires.

The Byzantines' ally was a Christian Arabic tribe from the frontiers of the desert known as the Ghassanids. The Sasanians' ally; the Lakhmids, were also Christian Arabs, but from what is now Iraq. However, denominational disagreements about God forced a schism in the alliances. The Byzantines' official religion was Orthodox Christianity, which believed that Jesus Christ and God were two natures within one entity.[96] The Ghassanids, as Monophysite Christians from Iraq, believed that God and Jesus Christ were only one nature.[97] This disagreement proved irreconcilable and resulted[when?] in a permanent break in the alliance.

Meanwhile, the Sasanian Empire broke its alliance with the Lakhmids due to false accusations that the Lakhmids' leader had committed treason; the Sasanians annexed the Lakhmid kingdom in 602.[98] The fertile lands and important trade routes of Iraq were now open ground for upheaval.

Rise of Islam

editWhen the military stalemate was finally broken and it seemed that Byzantium had finally gained the upper hand in battle, nomadic Arabs invaded from the desert frontiers, bringing with them a new social order that emphasized religious devotion over tribal membership.

The political apparatus created by Muhammad (d. 632) was able to conquer Arabia within a few years of his death. Afterwards, this group invaded the Near East into both Sasanian and Byzantine territory. Within a few decades, the Sasanian empire had fallen entirely, with Byzantine territories in the Levant, the Caucasus, Egypt, Syria and North Africa also taken.[91][need quotation to verify] By the end of the seventh century, an empire stretching from the Pyrenees Mountains in Europe to the Indus River valley in South Asia had been established.[99]

See also

edit- Ancient Near East

- Arab (etymology)

- Arabian mythology

- Dilmun

- History of Saudi Arabia

- History of Bahrain

- History of the Arabic alphabet

- History of the United Arab Emirates

- Incense Route

- Jahiliyyah

- Pre-Islamic Arab trade

- Pre-Islamic calendar

- Rahmanism

- Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam

- Women in pre-Islamic Arabia

Notes

edit- ^ a b Kenneth A. Kitchen The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110

- ^ Taylor, Jane (2005). Petra. London: Aurum Press Ltd. pp. 25–31. ISBN 9957-451-04-9.

- ^ Lindstedt 2023, p. 1–144.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Munt 2014, p. 21–22.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 8–9.

- ^ MacDonald 2015, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Hoyland 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Cameron, Averil (1993). The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity. Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 9781134980819. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 5. BRILL. 1993. p. 98. ISBN 978-9004097919. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. BRILL. pp. XXIV–XXVI. ISBN 978-9004107632. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Robert Bertram Serjeant (1968). "Fisher-folk and fish-traps in al-Bahrain". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 31 (3): 486–514. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00125522. JSTOR 614301. S2CID 128833964.

- ^ Patricia Crone (2005). Medieval Islamic Political Thought. p. 371. ISBN 9780748621941. Archived from the original on 2021-06-14. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ G. J. H. van Gelder (2005). Close Relationships: Incest and Inbreeding in Classical Arabic Literature. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 110. ISBN 9781850438557. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ Matt Stefon (2009). Islamic Beliefs and Practices. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 36. ISBN 9781615300174.

- ^ Zanaty, Anwer Mahmoud. Glossary Of Islamic Terms. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Jastrow, Otto (2002). Non-Arabic Semitic elements in the Arabic dialects of eastern Arabia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 270–279. ISBN 9783447044912. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. BRILL. pp. XXIX–XXX. ISBN 978-9004107632. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ a b Hoyland 2002, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Jesper Eidema, Flemming Højlundb (1993). "Trade or diplomacy? Assyria and Dilmun in the eighteenth century BC". World Archaeology. 24 (3): 441–448. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980218.

- ^ Crawford, Harriet E. W. (1998). Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbours. Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780521586795.

- ^ "Bahrain digs unveil one of oldest civilisations". BBC News. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Qal'at al-Bahrain – Ancient Harbour and Capital of Dilmun". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Rice, Michael (1991). Egypt's Making: The Origins of Ancient Egypt 5000-2000 BC. Routledge. p. 230. ISBN 9781134492633.

- ^ a b Edward Conklin (1998). Getting Back Into the Garden of Eden. University Press of America. p. 10. ISBN 9780761811404. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ Thorkild Jacobsen (23 September 1997). The Harps that once--: Sumerian poetry in translation, p. 150. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ Larsen 1983, p. 50-51.

- ^ Crawford, Harriet; Rice, Michael (2000). Traces of Paradise: The Archaeology of Bahrain, 2500 BC to 300 AD. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 217. ISBN 9781860647420. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Magee, Peter (2014). The Archaeology of Prehistoric Arabia: Adaptation and Social Formation from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0-521-86231-8.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 24–26.

- ^ Retsö, Jan (2014). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. Taylor & Francis. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-0-7007-1679-1.

- ^ Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarcheology of an Ancient Society By Curtis E. Larsen p. 13

- ^ a b c d e Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography By Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, page 119

- ^ Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren, Historical Researches Into the Politics, Intercourse, and Trade of the Principal Nations of Antiquity, Henry Bohn, 1854 p38

- ^ Arnold Heeren, ibid, p441

- ^ See Ares, Ares in the Arabian Peninsula section

- ^ Morris, Ian (1994). Classical Greece: Ancient Histories and Modern Archaeologies. Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Phillip Ward, Bahrain: A Travel Guide, Oleander Press p68

- ^ W. B. Fisher et al. The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press 1968 p40

- ^ "AUB academics awarded $850,000 grant for project on the Syriac writers of Qatar in the 7th century AD" (PDF). American University of Beirut. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Nestorian Christianity in the Pre-Islamic UAE and Southeastern Arabia" Archived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, Peter Hellyer, Journal of Social Affairs, volume 18, number 72, winter 2011, p. 88

- ^ a b c d "Christianity in the Gulf during the first centuries of Islam" (PDF). Oxford Brookes University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984.

- ^ Kozah, Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim. p. 1.

- ^ Fromherz, Allen (13 April 2012). Qatar: A Modern History. Georgetown University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-58901-910-2.

- ^ a b Bahrain By Federal Research Division, page 7

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge 2001p28

- ^ a b c Conflict and Cooperation: Zoroastrian Subalterns and Muslim Elites in ... By Jamsheed K. Choksy, 1997, page 75

- ^ Yoma 77a and Rosh Hashbanah, 23a

- ^ Strong's Hebrew and Aramaic Dictionary of Bible Words

- ^ Haldon, John; Fleitmann, Dominik (2024). "A Sixth-Century CE Drought in Arabia New Palaeoclimate Data and Some Historical Implications". Journal of Late Antique, Islamic and Byzantine Studies. 3 (1–2): 1–45. doi:10.3366/jlaibs.2023.0024. ISSN 2634-2367.

- ^ Fleitmann, Dominik; Haldon, John; Bradley, Raymond S.; Burns, Stephen J.; Cheng, Hai; Edwards, R. Lawrence; Raible, Christoph C.; Jacobson, Matthew; Matter, Albert (2022-06-17). "Droughts and societal change: The environmental context for the emergence of Islam in late Antique Arabia". Science. 376 (6599): 1317–1321. doi:10.1126/science.abg4044. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Nebes, Norbert. "Epigraphic South Arabian", Encyclopaedia: D-Ha pp. 334; Leonid Kogan and Andrey Korotayev: Ṣayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian) // Semitic Languages. London: Routledge, 1997, p. 157–183.

- ^ "Yemen's history and its originality:Report. - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ Minaeans.

- ^ "Dead link". Archived from the original on 2007-11-12.

- ^ Sima, Alexander. "Dʿmt" in Siegbert Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 185.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart. Aksum: a Civilization of Late Antiquity, (Edinburgh: University Press, 1991), p. 58.

- ^ Müller, Walter W. "Ḥaḍramawt"Encyclopaedia: D-Ha, pp. 965–66.

- ^ Yule, Paul. Himyar Spätantike im Jemen Late Antique Yemen 2007, pp. map. p. 16 Fog. 3,45–55.

- ^ Sima, Alexander. "GDR(T)", Encyclopaedia: D-Ha, p. 718–9.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 72.

- ^ Yule, Paul, A Late Antique christian king from Ẓafār, southern Arabia, Antiquity 87, 2013, 1124-35.

- ^ Rohmer & Charloux 2015, p. 297.

- ^ Mackintosh-Smith 2019, p. 29.

- ^ Firestone 2006.

- ^ Mackintosh-Smith 2019, p. 30.

- ^ DNa - Livius. p. DNa inscription Line 27. Archived from the original on 2021-03-25. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N.; Langer, William Leonard (2001), The Encyclopedia of world history: ancient, medieval, and modern, chronologically arranged (6th, illustrated ed.), Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 41, ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4

- ^ "Arabia". Archived from the original on 2013-09-01. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Encyclopædia Iranica Archived November 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Saudi Aramco World : Well of Good Fortune". Saudiaramworld.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ D. H. Müller, Al-Hamdani, 53, 124, W. Caskel, Entdeckungen In Arabien, Koln, 1954, S. 9. Mahram, P.318

- ^ History of Arabia – Kindah Archived 2015-04-03 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Le Muséon, 3-4, 1953, P.296, Bulletin Of The School Of Oriental And African Studies, University Of London, Vol., Xvi, Part: 3, 1954, P.434, Ryckmans 508

- ^ Jamme 635. See: Jawād 'Alī: Al-Mufaṣṣal fī Tārīkh al-'Arab Qabl al-Islam, Part 39.

- ^ a b c Parolin, Gianluca P. (2009). Citizenship in the Arab World: Kin, Religion and Nation-State. Amsterdam University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-9089640451. "The 'arabicised or arabicising Arabs', on the contrary, are believed to be the descendants of Ishmael through Adnan, but in this case the genealogy does not match the Biblical line exactly. The label 'arabicised' is due to the belief that Ishmael spoke Hebrew until he got to Mecca, where he married a Yemeni woman and learnt Arabic. Both genealogical lines go back to Sem, son of Noah, but only Adnanites can claim Abraham as their ascendant, and the lineage of Mohammed, the Seal of Prophets (khatim al-anbiya'), can therefore be traced back to Abraham. Contemporary historiography unveiled the lack of inner coherence of this genealogical system and demonstrated that it finds insufficient matching evidence; the distinction between Qahtanites and Adnanites is even believed to be a product of the Umayyad Age, when the war of factions (al-niza al-hizbi) was raging in the young Islamic Empire."

- ^ Reuven Firestone (1990). Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. SUNY Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780791403310. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ Göran Larsson (2003). Ibn García's Shuʻūbiyya Letter: Ethnic and Theological Tensions in Medieval al-Andalus. BRILL. p. 170. ISBN 978-9004127401. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ "MANICHEISM v. MISSIONARY ACTIVITY AND TECHNIQUE: Manicheism in Arabia". Archived from the original on 2019-11-16. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

That Manicheism went further on to the Arabian peninsula, up to the Hejaz and Mecca, where it could have possibly contributed to the formation of the doctrine of Islam, cannot be proven. A detailed description of Manichean traces in the Arabian-speaking regions is given by Tardieu (1994).

- ^ M. Tardieu, "Les manichéens en Egypte," Bulletin de la Société Française d'Egyptologie 94, 1982, pp. 5-19.

- ^ Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Sidky, Hythem (2022). "A Paleo-Arabic inscription on a route north of Ṭāʾif". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 33 (1): 202–215. doi:10.1111/aae.12203. ISSN 0905-7196.

- ^ MacDonald 2015, p. 29.

- ^ Al-Jallad 2020.

- ^ Van Putten 2023.

- ^ a b Cole 2020.

- ^ MacDonald 2015b, p. 44–56.

- ^ Villeneuve 2004.

- ^ Millar 2009.

- ^ Klasova 2023, p. 3–4.

- ^ a b Liska, George (1998). Expanding Realism: The Historical Dimension of World Politics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 9780847686797. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

- ^

Compare:

Ibrahim, Hayder (1979). "The Region: Time and Space". The Shaiqiya: the cultural and social change of a Northern Sudanese riverain people. Studien zur Kulturkunde. Vol. 49. Steiner. p. 7. ISBN 9783515029070. Retrieved 2018-02-08.

There was a continuous migration from Arabia to the neighbouring regions, because the Arabian peninsula was overpopulated and lacked resources and periodic drought drove the people out of the region. [...] The overflow of migration accelerated during the Islamic expansion [...].

- ^ "Bury, John.", "A history of the later Roman empire: from Arcadius to Irene.", "(New York: 1889)", "401"

- ^ "Sicker, Martin", "The Pre-Islamic Middle East","(Connecticut:2000)", "201."

- ^ "Egger, Vernon", "Origins" in A History of the Muslim World to 1405: The Making of a Civilization", "(New Jersey: 2005)", "10"

- ^ "Ware, Timothy", "The Orthodox Church", "(New York:1997)", "67 – 69"

- ^ "Bowersock", "Brown", and "Grabar", ""Alphabetical Guide" in Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Post-Classical World", "(Cambridge: 2000)", "469".

- ^ "Singh, Nagendra", "International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties", "(India: 2005)", "75"

- ^ "Egger", "2005", "33"

Bibliography

edit- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2020). "The Linguistic Landscape of pre-Islamic Arabia: Context for the Qur'an". In Shah, Mustafa; Haleem, M.A.S. Abdel (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Qur'anic Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 111–127.

- Cole, Juan (2020). "Muhammad and Justinian: Roman Legal Traditions and the Qurʾān". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 79 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1086/710188.

- Firestone, Reuven (2006), "Thamūd", in McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān, Volume Five, Brill, pp. 252–254, ISBN 978-9004123564.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2002), Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-64634-0

- Kaizer, Ted (2008), The Variety of Local Religious Life in the Near East: In the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-16735-3

- Klasova, Pamela (2023). "Arabic Poetry in Late Antiquity: The Rāʾiyya of Imruʾ al-Qays". In Fakhreddine, Huda; Stetkevych, Suzanne Pinckney (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Poetry. Routledge. pp. 1–26.

- Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim (2014), The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century, Gorgias Press, LLC, ISBN 978-1-4632-0355-9

- Lindstedt, Ilkka (2023). Muhammad and His Followers in Context: The Religious Map of Late Antique Arabia. Brill.

- MacDonald, Michael C.A. (2015). "On the Uses of Writing in Ancient Arabia and the Role of Palaeography in Studying Them". Arabian Epigraphic Notes. 1: 1–50.

- MacDonald, Michael (2015b). "Arabs and Empires before the Sixth Century". In Fisher, Greg (ed.). Arabs and Empires before Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 11–89.

- Mackintosh-Smith, Tim (2019). Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires. Yale University Press.

- Millar, Fergus (2009). "Christian Monasticism in Roman Arabia at the Birth of Mahomet". Semitica et Classica. 2: 97–115. doi:10.1484/J.SEC.1.100512.

- Munt, Thomas (2014). The Holy City of Medina: Sacred Space in Early Islamic Arabia. Cambridge University Press.

- Rohmer, Jérôme; Charloux, Guillaume (2015). "From Liḥyān to the Nabataeans: Dating the End of the Iron Age in Northwestern Arabia". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 45: 297–320.

- Stein, Peter (2009). "Literacy In Pre-Islamic Arabia: An Analysis of The Epigraphic Evidence". In Marx, Michael; Neuwirth, Angelika; Sinai, Nicolai (eds.). The Qurʾān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu. Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān. Vol. 6. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 255–280. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004176881.i-864.58. ISBN 978-90-04-17688-1. ISSN 1567-2808. S2CID 68889318.

- Sykes, Egerton (2014), Who's Who in Non-Classical Mythology, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-41437-4

- Van Putten, Marijn (2023). "The Development of the Hijazi Orthography". Millennium. 20 (1): 107–128. doi:10.1515/mill-2023-0007. hdl:1887/3715910.

- Villeneuve, François (2004). "Une inscription latine sur l'archipel Farasân, Arabie Séoudite, sud de la mer Rouge". Année. 148 (1): 419–429.

- Waardenburg, Jean Jacques (2003), "The Earliest Relations of Islam with Other Religions: The Meccan Polytheists", Muslims and Others: Relations in Context, Religion and Reason, vol. 41, Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 89–91, doi:10.1515/9783110200959, ISBN 978-3-11-017627-8

Further reading

edit- Berkey, Jonathan P. (2003), The Formation of Islam, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-58813-3

- Bulliet, Richard W. (1975), The Camel and the Wheel, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-09130-6

- Donner, Fred (1981), The Early Islamic Conquests, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-10182-8

- Hawting, G. R. (1999), The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65165-3

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2001), Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-19535-5

- Korotayev, Andrey (1995), Ancient Yemen, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922237-7

- Korotayev, Andrey (1996), Pre-Islamic Yemen, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-03679-5

- Yule, Paul Alan (2007), Himyar–Die Spätantike im Jemen/Himyar Late Antique Yemen, Aichwald: Linden, ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6

- Arabia Antica Archived 2006-02-16 at the Wayback Machine: Portal of Pre-Islamic Arabian Studies, University of Pisa - Dipartimento Civiltà e Forme del Sapere