Zero Dark Thirty is a 2012 American political action thriller film directed and produced by Kathryn Bigelow, and written and produced by Mark Boal. The film dramatizes the nearly decade-long international manhunt for Osama bin Laden, leader of the terrorist network Al-Qaeda, after the September 11 attacks. This search leads to the discovery of his compound in Pakistan and the U.S. military raid where bin Laden was killed on May 2, 2011.

| Zero Dark Thirty | |

|---|---|

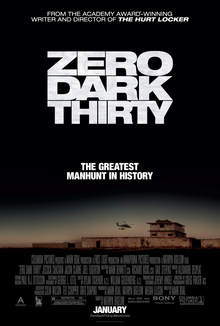

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Kathryn Bigelow |

| Written by | Mark Boal |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Greig Fraser |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 157 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $40–52.5 million[2][4] |

| Box office | $132.8 million[2] |

Jessica Chastain stars as Maya, a fictional CIA intelligence analyst, with Jason Clarke, Joel Edgerton, Reda Kateb, Mark Strong, James Gandolfini, Kyle Chandler, Stephen Dillane, Chris Pratt, Édgar Ramírez, Fares Fares, Jennifer Ehle, John Barrowman, Mark Duplass, Harold Perrineau, and Frank Grillo in supporting roles.[5][6] It was produced by Boal, Bigelow, and Megan Ellison, and independently financed by Ellison's Annapurna Pictures. The film premiered in Los Angeles on December 10, 2012, and had its wide release on January 11, 2013.[7]

Zero Dark Thirty received critical acclaim for its acting, direction, screenplay, sound design, and editing, and was a major box office success, grossing $132 million worldwide. It appeared on 95 critics' top ten lists of 2012. It was also nominated in five categories at the 85th Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actress for Chastain, Best Original Screenplay, Best Film Editing, and Best Sound Editing, which it won in a tie with Skyfall. It earned four Golden Globe Award nominations, including Best Actress in a Motion Picture (Drama) for Chastain, who won.

The film was accused of being pro-torture by U.S. senators John McCain, Dianne Feinstein and Carl Levin.

Plot

editMaya is a CIA analyst tasked with finding the al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. In 2003, she is stationed at the U.S. embassy in Pakistan. She and CIA officer Dan Fuller attend the black site interrogations of Ammar (Reda Kateb), a detainee with suspected links to several of the hijackers in the September 11 attacks and who is subjected to approved enhanced interrogation techniques. Ammar provides unreliable information on a suspected attack in Saudi Arabia, but reveals the name of the personal courier for bin Laden, Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. Other detainee intelligence connects courier traffic by Abu Ahmed between Abu Faraj al-Libbi and bin Laden. In 2005, Faraj denies knowing about a courier named Abu Ahmed; Maya interprets this as an attempt by Faraj to conceal the importance of Abu Ahmed.

In 2009, Maya's fellow officer and friend Jessica travels to a US base in Afghanistan to meet a Jordanian doctor, highly placed in al-Qaeda, who has offered to become a US spy for $25 million. Instead, he turns out to be a triple agent loyal to al-Qaeda, and Jessica is killed, along with several other CIA officers, when he detonates a suicide vest in what will come to be known as the Camp Chapman attack, the worst attack on CIA personnel in 25 years.

Thomas, an analyst who linked the Abu Ahmed lead, shares with Maya an interrogation of a Jordanian detainee claiming to have buried Abu Ahmed in 2001. Maya learns what the CIA was told five years earlier: Ibrahim Sayeed traveled under the name of Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti. Realizing her lead may be alive, Maya contacts Dan, now a senior officer at the CIA headquarters. She speculates that the CIA's photograph of Ahmed is that of his brother, Habeeb, who was killed in Afghanistan. Maya says that their beards and native clothes make the brothers look alike, explaining the account of Ahmed's "death" in 2001.

A Kuwaiti prince trades the phone number of Sayeed's mother to Dan for a Lamborghini Gallardo Bicolore. Maya and her CIA team in Pakistan use electronic methods to eventually pinpoint a caller in a moving vehicle who exhibits behaviors that delay confirmation of his identity (which Maya calls tradecraft, thus confirming that the subject is likely a senior courier). They track the vehicle to a large urban compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. After gunmen attack Maya while she is in her vehicle, she is recalled to Washington, D.C. as her cover is believed blown.

The CIA puts the compound under surveillance but obtains no conclusive identification of bin Laden. The President's National Security Advisor tasks the CIA with creating a plan to capture or kill bin Laden. Before briefing President Barack Obama, the CIA director holds a meeting of his senior officers, who estimate that bin Laden is 60–80% likely to be in the compound. Maya, also in the meeting, places her confidence at 100%.

On May 2, 2011, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment flies two stealth helicopters from Afghanistan into Pakistan with members of DEVGRU (SEAL Team Six) and the CIA's Special Activities Division to raid the compound. The SEALs gain entry and kill several people in the compound, including a man whom they believe is bin Laden. At a U.S. base in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, Maya confirms the identity of the corpse.

She boards a military transport back to the U.S., the sole passenger. She is asked where she wants to go and begins to cry.

Cast

editCIA

- Jessica Chastain as Maya, a CIA intelligence analyst (a composite character modeled in part after Alfreda Frances Bikowsky)

- Jason Clarke as Dan Fuller, a CIA intelligence officer

- Jennifer Ehle as Jessica Karley, a senior CIA analyst

- Mark Strong as George, a senior CIA supervisor

- Kyle Chandler as Joseph Bradley, Islamabad CIA Station Chief

- James Gandolfini as CIA Director Leon Panetta

- Harold Perrineau as Jack Fuller, a CIA analyst

- Mark Duplass as Steve Bradley, a CIA analyst

- Fredric Lehne as Fred "The Wolf" Guerrero, a CIA section chief

- John Barrowman as Jeremy Karley, a CIA executive

- Jessie Collins as Debbie Stone, a CIA analyst

- Édgar Ramírez as Larry Handley, a CIA SAD/SOG operative

- Fares Fares as Hakim, a CIA SAD/SOG operative

- Scott Adkins as John Simmons, a CIA SAD/SOG operative

- Jeremy Strong as Thomas, a CIA analyst

US Navy

- Joel Edgerton as Patrick Grayston, DEVGRU (SEAL Team 6) team leader

- Chris Pratt as Justin Lenihan, DEVGRU operator.

- Callan Mulvey as Saber Till, DEVGRU operator.

- Taylor Kinney as Jared Bradley, DEVGRU operator

- Mike Colter as Mike, DEVGRU operator

- Frank Grillo as DEVGRU Commanding officer

- Christopher Stanley as JSOC Commander Vice Admiral Bill McRaven[N 1]

Other

- Stephen Dillane as National Security Advisor Tom Donilon

- Mark Valley as C-130 pilot

- John Schwab as Deputy National Security Advisor

- Reda Kateb as Ammar, a terrorist who is tortured for information

- Homayoun Ershadi as Hassan Ghul

- Yoav Levi as Abu Farraj al-Libbi

- Ricky Sekhon as Osama bin Laden, leader and founder of Al Qaeda

- Ali Marhyar as interrogator on monitor

Production

editTitles

editThe film's working title was For God and Country.[8] The title Zero Dark Thirty was officially confirmed at the end of the film's teaser trailer.[9] Bigelow has explained that "it's a military term for early morning before dawn, and it refers also to the darkness and secrecy that cloaked the entire decade-long mission."[10]

Writing

editKathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal had initially worked on and finished a screenplay centered on the December 2001 Battle of Tora Bora, and the long, unsuccessful efforts to find Osama bin Laden in the region. The two were about to begin filming when news broke that bin Laden had been killed.

They immediately shelved the film they had been working on and redirected their focus, essentially starting from scratch. "But a lot of the homework I'd done for the first script and a lot of the contacts I made, carried over," Boal remarked during an interview with Entertainment Weekly. He added, "The years I had spent talking to military and intelligence operators involved in counter-terrorism was helpful in both projects. Some of the sourcing I had developed long, long ago continued to be helpful for this version."[10]

Along with painstakingly recreating the historic night-vision raid on the Abbottabad compound, the script and the film stress the little-reported role of the tenacious young female CIA officer who tracked down Osama bin Laden. Screenwriter Boal said that while researching for the film, "I heard through the grapevine that women played a big role in the CIA in general and in this team. I heard that a woman was there on the night of the raid as one of the CIA's liaison officers on the ground – and that was the start of it." He then turned up stories about a young case officer who was recruited out of college, who had spent her entire career chasing bin Laden. Maya's tough-minded, monomaniacal persona, Boal said, is "based on a real person, but she also represents the work of a lot of other women."[11] In December 2014 Jane Mayer of The New Yorker wrote that "Maya" was modeled in part after CIA officer Alfreda Frances Bikowsky.[12]

Filming

editZero Dark Thirty producers built a real compound in Jordan, based on what they could learn (from diagrams and reporting) about the building where the CIA's pursuit ended. The production designer—Jeremy Hindle, who had never made a feature film before—was responsible for making the building as real as possible. The cinder blocks with which the building was made, for example, were distressed so that they didn't look new. Parts of the film were shot at PEC University of Technology in Chandigarh, India.[13][14] Some parts of Chandigarh were designed to look like Lahore and Abbottabad in Pakistan, where Osama bin Laden was found and killed on May 2, 2011.[15] Parts of the film were shot in Mani Majra.[16] Local members of right-wing parties protested, expressing anti-bin Laden and anti-Pakistan sentiments as they objected to Pakistani locations being portrayed on Indian soil.[17][18] For a lone scene shot in Poland, the city of Gdańsk was reportedly offended for depicting it as a location for the CIA's clandestine and dark operations.[19]

National security expert Peter Bergen, who reviewed an early cut of the film as an unpaid adviser, said at the time that the film's torture scenes "were overwrought". Boal said they were "toned down" in the final cut.[20]

Music

editAlexandre Desplat composed and conducted the film's score.[21] The score, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, was released as a soundtrack album by Madison Gate Records on December 19, 2012.[22]

Release

editDistribution

editColumbia Pictures distributed the film in the United States with Annapurna Pictures' international sales arm Panorama Media handling international rights, Universal Pictures International co-distributed the film with Panorama in select European territories and South Africa. Icon Film Distribution distributed the film in Australia and Entertainment One distributed the film in Canada.

Marketing

editElectronic Arts promoted Zero Dark Thirty in its video game Medal of Honor: Warfighter by offering downloadable maps of locations depicted in the film. Additional maps for the game were made available on December 19, to coincide with the film's initial release. Electronic Arts donates $1 to nonprofit organizations that support veterans for each Zero Dark Thirty map pack sold.[23]

Theatrical

editThe film premiered in Los Angeles on December 10, 2012.[7] It had a limited theatrical release on December 19, 2012, before expanding wide on January 11, 2013.

Home media

editZero Dark Thirty was released on DVD[24] and Blu-ray Disc on March 26, 2013.[25]

Reception

editBox office

editThe limited release of Zero Dark Thirty grossed $417,150 in the United States and Canada in only five theaters.[26] A wide release followed on January 11.

Entertainment Weekly wrote, "The controversial Oscar contender easily topped the chart in its first weekend of wide release with $24.4 million."[27] Zero Dark Thirty grossed $95,720,716 in the U.S. and Canada, along with $37,100,000 in other countries, for a worldwide total of $132,820,716.[2] It was the top-grossing film of its wide release premiere weekend.[28]

Critical response

editOn Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 91% based on 302 reviews, with an average rating of 8.60/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Gripping, suspenseful, and brilliantly crafted, Zero Dark Thirty dramatizes the hunt for Osama bin Laden with intelligence and an eye for detail."[29] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 95 out of 100, based on 46 critics, indicating "universal acclaim". It was the site's best-reviewed film of 2012.[30] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[31]

New York Times critic Manohla Dargis, who designated the film a New York Times critics' pick, said that the film "shows the dark side of that war. It shows the unspeakable and lets us decide if the death of Bin Laden was worth the price we paid."[32]

Richard Corliss's review in Time magazine called it "a fine" movie and "a police procedural on the grand scale", saying it "blows Argo out of the water".[33] Calling Zero Dark Thirty "a milestone in post-Sept. 11 cinema", critic A. O. Scott of The New York Times listed the film at number six of the top 10 films of 2012.[34]

The New Yorker film critic David Denby lauded the filmmakers for their approach. "The virtue of Zero Dark Thirty", wrote Denby, "is that it pays close attention to the way life does work; it combines ruthlessness and humanity in a manner that is paradoxical and disconcerting yet satisfying as art." But Denby faulted the filmmakers for getting lodged on the divide between fact and fiction.[35]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars out of four.[36] He believed the "opening scenes are not great filmmaking", but Ebert thought Zero Dark Thirty eventually proved itself with the quiet determination of Chastain's performance and a gripping portrayal of the behind-the-scenes detail that led to bin Laden's death.

Top ten lists

editZero Dark Thirty was listed on many critics' top ten lists. According to Metacritic the film appeared on 95 critics' top ten lists of 2012, 17 of which placed the film at No. 1.[37][38][39]

- 1st – Richard Roeper

- 1st – David Denby, The New Yorker (tied with Lincoln)

- 1st – Lisa Schwarzbaum, Entertainment Weekly

- 1st – Michael Phillips, Chicago Tribune

- 1st – Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post

- 1st – Scott Foundas, Village Voice

- 1st – Mary Pols, Time

- 1st – David Edelstein, New York

- 1st – Peter Knegt & Nigel M. Smith, Indiewire

- 1st – Christopher Orr, The Atlantic

- 1st – Keith Phipps, The A.V. Club

- 2nd – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 2nd – Eric Kohn, Indiewire

- 2nd – Stephanie Zacharek, Film.com

- 2nd – Joshua Rothkopf, Time Out New York

- 2nd – A.A. Dowd and Ben Kenigsberg, Time Out Chicago

- 2nd – Noel Murray, The A.V. Club

- 2nd – Gregory Ellwood, Hitfix

- 2nd – Scott Mantz, Access Hollywood

- 2nd – James Berardinelli, Reelviews

- 3rd – Stephen Holden, The New York Times

- 3rd – Ty Burr, The Boston Globe

- 3rd – Betsy Sharkey, Los Angeles Times

- 3rd – Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle

- 3rd – Elizabeth Weitzman, New York Daily News

- 3rd – Bill Goodykoontz, The Arizona Republic

- 3rd – Anne Thompson & Caryn James, IndieWire

- 3rd – Tasha Robinson, The A.V. Club

- 4th – Andrew O'Hehir, Salon.com

- 4th – Glenn Kenny, MSN Movies

- 4th – Marlow Stern, The Daily Beast

- 5th – Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly

- 5th - Christy Lemire, Associated Press

- 5th – Drew McWeeny, HitFix

- 5th – Todd McCarthy, The Hollywood Reporter

- 6th – Richard Corliss, Time

- 6th – A.O. Scott, The New York Times

- 7th – Kevin Jagernauth, IndieWire

- 7th – Lisa Kennedy, The Denver Post

- 7th – Alison Willmore, The A.V. Club

- 8th – Scott Tobias, The A.V. Club

- 9th – Keith Uhlich, Time Out New York

- 9th – Joe Neumaier, New York Daily News

- 10th – Steven Rea, The Philadelphia Inquirer

- 10th – Dana Stevens, Slate

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Richard Lawson, The Atlantic

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Manohla Dargis, The New York Times

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Calvin Wilson, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Joe Morgenstern, The Wall Street Journal

- Best of 2012 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times

In 2016, Zero Dark Thirty was voted the 57th greatest film to be released since 2000 in a critics' poll conducted by the BBC.[40]

Accolades

editZero Dark Thirty was nominated for five Academy Awards at the 85th Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Original Screenplay, Best Sound Editing and Best Film Editing. Paul N. J. Ottosson won the Academy Award for Best Sound Editing, tying with Skyfall. This was only the sixth tie in Academy Awards history, and the first since 1994. Zero Dark Thirty was nominated for four Golden Globe Awards at the 70th Golden Globe Awards, including Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director, Best Screenplay, with Chastain winning Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama.

The Washington D.C. Area Film Critics Association's award for Best Director was given to Bigelow, the second time the honor has gone to a woman (the first also being Bigelow for The Hurt Locker). The film swept critics groups' awards for Best Director and Best Picture including the Washington D.C., New York Film Critics Online, Chicago and Boston film critics associations.[41]

Historical accuracy

editZero Dark Thirty has received criticism for historical inaccuracy. Former Assistant Secretary of Defense Graham T. Allison has stated that the film is inaccurate in three important regards: the overstatement of the positive role of torture, the understatement of the role of the Obama administration, and the portrayal of the efforts as being driven by one agent battling against the CIA "system".[42]

Steve Coll criticized the early depictions in the film that portrayed it as "journalism" with the use of composite characters. He took issue with the film's using the names of historical figures and details of their lives for characters, such as using details for "Ammar" to suggest that he was Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, whose nom de guerre was Ammar al-Baluchi. Coll said the facts about him were different from what was portrayed in the film, which suggests the detainee will never leave the black site. Al-Baluchi was transferred to Guantanamo in 2006 for a military tribunal.[43]

It was also criticized for its stereotypical portrayal of Pakistan as well as the inaccurate portrayal of Pakistani nationals speaking Arabic instead of Urdu and other regional languages, and locals wearing obsolete headgear.[44]

Controversies

editAllegations of partisanship

editPartisan political controversy related to the film arose before shooting began.[10] Opponents of the Obama Administration charged that Zero Dark Thirty was scheduled for an October release just before the November presidential election to support his re-election.[45][46] Sony denied that politics was a factor in release scheduling and said the date was the best available spot for an action-thriller in a crowded lineup. The film's screenwriter added, "the president is not depicted in the movie. He's just not in the movie."[47]

The distributor, Columbia Pictures, sensitive to political perceptions, considered rescheduling the film release for as late as early 2013. It set a limited-release date for December 19, 2012, well after the election and rendering moot any alleged political conflict.[8][48][49][50][51] The nationwide release date was pushed back to January 11, 2013, moving it out of the crowded Christmas period and closer to the Academy Awards.[52] After the film's limited release, given the controversy related to the film's depiction of torture and its role in gaining critical information, The New York Times columnist Frank Bruni concluded that the film is "a far, far cry from the rousing piece of pro-Obama propaganda that some conservatives feared it would be".[53] Two months later, the paper's columnist Roger Cohen wrote that the film was "a courageous work that is disturbing in the way that art should be". Cohen disagreed with Steve Coll's critique of the screenwriter's stated effort not to "play fast and loose with history", writing that "Boal has honored those words". Cohen ended with a note about a Timothy Garton Ash analysis of George Orwell mixing fact and "invented" stories in Down and Out in Paris and London – as further support for Boal's method.[54]

Allegations of improper access to classified information

editSeveral Republican sources charged the Obama Administration of improperly providing Bigelow and her team access to classified information during their research for the film. These charges, along with charges of other leaks to the media, became a prevalent election season talking point by conservatives. The Republican national convention party platform even claimed Obama "has tolerated publicizing the details of the operation to kill the leader of Al Qaeda."[49] No release of these details has been proven according to the Navy Times.[55]

The Republican congressman Peter T. King requested that the CIA and the U.S. Defense Department investigate if classified information was inappropriately released; both departments said they would look into it.[56] The CIA responded to Congressman King writing, "the protection of national security equities – including the preservation of our ability to conduct effective counterterrorism operations – is the decisive factor in determining how the CIA engages with filmmakers and the media as a whole."[57]

The conservative watchdog group Judicial Watch publicized CIA and U.S. Defense Department documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, and alleged that "unusual access to agency information" was granted to the filmmakers. An examination of the documents showed no evidence that classified information was leaked to the filmmakers. In addition, CIA records did not show any involvement by the White House in relation to the filmmakers.[8][49] The filmmakers have said they were not given access to classified details about Osama bin Laden's killing.[58] In 2012, Judicial Watch released an article stating the Obama Administration admitted that the information provided to the production team could pose an "unnecessary security and counterintelligence risk" if the information were to be released to the public. Judicial Watch also found emails containing information on five CIA and military operatives that were involved in the Bin Laden operations. These emails were provided to the filmmakers, as was later confirmed by the Obama Administration in a sworn declaration.[59]

In January 2013, Reuters reported that the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence would review the contacts between the CIA and the filmmakers to find out whether Bigelow and Boal had inappropriate access to classified information.[60] In February, Reuters reported that the inquiry had been dropped.[61]

In June 2013, information was released in regards to an unreleased U.S. Defense Department Inspector General's office report. It stated that in June 2011, while giving a speech at a CIA Headquarters event honoring the people involved in the Osama Bin Laden raid, CIA Director Leon Panetta disclosed information classified as "Secret" and "Top Secret" regarding personnel involved in the raid on the Bin Laden compound.[62] He identified the unit that conducted the raid as well as naming the ground commander that was in charge. Panetta also revealed DoD information during his speech that was classified as "Top Secret". Unknown to him, screenwriter Mark Boal was among the around 1300 present during the ceremony.[63]

Allegations of pro-torture stance

editThe film has been both criticized and praised for its handling of its subject matter, including the portrayal of the harsh "enhanced interrogation techniques", commonly classified as torture. The use of these techniques was long kept secret by the Bush administration. (See Torture Memos, The Torture Report.) Glenn Greenwald, in The Guardian, stated that the film takes a pro-torture stance, describing it as "pernicious propaganda" and stating that it "presents torture as its CIA proponents and administrators see it: as a dirty, ugly business that is necessary to protect America."[64] Critic Frank Bruni concluded that the film appears to suggest "No waterboarding, no Bin Laden".[53] Jesse David Fox writes that the film "doesn't explicitly say that torture caught bin Laden, but in portraying torture as one part of the successful search, it can be read that way."[65] Emily Bazelon said, "The filmmakers didn't set out to be Bush-Cheney apologists", but "they adopted a close-to-the-ground point of view, and perhaps they're in denial about how far down the path to condoning torture this led them."[66]

Journalist Michael Wolff slammed the film as a "nasty piece of pulp and propaganda" and Bigelow as a "fetishist and sadist" for distorting history with a pro-torture viewpoint. Wolff disputed the efficacy of torture and the claim that it contributed to the discovery of bin Laden.[67] In an open letter, social critic and feminist Naomi Wolf criticized Bigelow for claiming the film was "part documentary" and speculated over the reasons for Bigelow's "amoral compromising" of film-making, suggesting that the more pro-military a film, the easier it is to acquire Pentagon support for scenes involving expensive, futuristic military equipment. Wolf likened Bigelow to the acclaimed director and propagandist for the Nazi regime Leni Riefenstahl, saying: "Like Riefenstahl, you are a great artist. But now you will be remembered forever as torture's handmaiden."[68] Author Karen J. Greenberg wrote that "Bigelow has bought in, hook, line, and sinker, to the ethos of the Bush administration and its apologists" and called the film "the perfect piece of propaganda, with all the appeal that naked brutality, fear, and revenge can bring".[69] Peter Maass of The Atlantic said the film "represents a troubling new frontier of government-embedded filmmaking".[70]

Jane Mayer of The New Yorker, who has published The Dark Side, a book about the use of torture during the Bush administration, criticized the film, saying that Bigelow was

milk[ing] the U.S. torture program for drama while sidestepping the political and ethical debate that it provoked ... [By] excising the moral debate that raged over the interrogation program during the Bush years, the film also seems to accept almost without question that the CIA's 'enhanced interrogation techniques' played a key role in enabling the agency to identify the courier who unwittingly led them to bin Laden.[71]

Author Greg Mitchell wrote that "the film's depiction of torture helping to get bin Laden is muddled at best – but the overall impression by the end, for most viewers, probably will be: Yes, torture played an important (if not the key) role."[72] Filmmaker Alex Gibney called the film a "stylistic masterwork" but criticized the "irresponsible and inaccurate" depiction of torture, writing:

there is no cinematic evidence in the film that EITs led to false information – lies that were swallowed whole because of the misplaced confidence in the efficacy of torture. Most students of this subject admit that torture can lead to the truth. But what Boal/Bigelow fail to show is how often the CIA deluded itself into believing that torture was a magic bullet, with disastrous results.[73]

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek, in an article for The Guardian, criticized what he perceived as a "normalization" of torture in the film, arguing that the mere neutrality on an issue many see as revolting is already a type of endorsement per se. Žižek proposed that if a similar film were made about a brutal rape or the Holocaust, such a movie would "embody a deeply immoral fascination with its topic, or it would count on the obscene neutrality of its style to engender dismay and horror in spectators." Žižek further panned Bigelow's stance of coldly presenting the issue in a rational manner, instead of being dogmatically rejected as a repulsive, unethical proposition.[74]

Journalist Steve Coll, who has written on foreign policy, national security and the bin Laden family, criticized the filmmakers for saying the film was "journalistic", which implies that it is based in fact. At the same time, they claimed artistic license, which he described "as an excuse for shoddy reporting about a subject as important as whether torture had a vital part in the search for bin Laden".[43] Coll wrote that "arguably, the film's degree of emphasis on torture's significance goes beyond what even the most die-hard defenders of the CIA interrogation regime ... have argued", as he said it was shown as critical at several points.[43]

U.S. Senator John McCain, who was tortured during his time as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, said that the film left him sick – "because it's wrong". In a speech in the Senate, he said, "Not only did the use of enhanced interrogation techniques on Khalid Sheikh Mohammed not provide us with key leads on bin Laden's courier, Abu Ahmed, it actually produced false and misleading information."[75] McCain and fellow senators Dianne Feinstein and Carl Levin sent a critical letter to Michael Lynton, chairman of the film's distributor, Sony Pictures Entertainment, stating, "[W]ith the release of Zero Dark Thirty, the filmmakers and your production studio are perpetuating the myth that torture is effective. You have a social and moral obligation to get the facts right."[76]

Michael Morell, the CIA's acting director, sent a public letter on December 21, 2012, to the agency's employees, which said that Zero Dark Thirty

takes significant artistic license, while portraying itself as being historically accurate ... [The film] creates the strong impression that the enhanced interrogation techniques that were part of our former detention and interrogation program were the key to finding Bin Ladin. That impression is false. ... [T]he truth is that multiple streams of intelligence led CIA analysts to conclude that Bin Ladin was hiding in Abbottabad. Some came from detainees subjected to enhanced techniques, but there were many other sources as well. And, importantly, whether enhanced interrogation techniques were the only timely and effective way to obtain information from those detainees, as the film suggests, is a matter of debate that cannot and never will be definitively resolved.[77]

The Huffington Post writer G. Roger Denson countered this, saying that the filmmakers were being made scapegoats for information openly admitted by government and intelligence officials. Denson said that Leon Panetta, three days after Osama bin Laden's death, seemed to say that waterboarding was a means of extracting reliable and crucial information in the hunt for bin Laden.[78] Denson noted Panetta speaking as the CIA chief in May 2011, saying that "enhanced interrogation techniques were used to extract information that led to the mission's success". Panetta said waterboarding was among the techniques used.[79] In a Huffington Post article written a week later, Denson cited other statements from Bush government officials saying that torture had yielded information to locate bin Laden.[78]

Human Rights Watch criticized the film for "wrongly suggest[ing] that torture was an ugly but useful tactic in the fight against terrorism", and for falsely depicting the use of torture as critical to leading to locating bin Laden, citing statements by McCain, Feinstein, Levin and Morell. The article also called for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence to declassify the report on torture adopted by the committee in December 2012 in order to "counter misinformation about the supposed value of “enhanced interrogation techniques” and to provide the public with a full accounting of past US government policy and practice."[80] Laura Pitter, the former deputy director of the US Program at HRW, criticized CIA counterterrorism chief Jose Rodriguez's response to the film, stating "[the film]... has spawned a wide array of commentary. None is as misleading or morally disturbing, however, as the one from... Rodriguez, who seized on the film as an opportunity to defend—and completely distort—the CIA torture program he supervised. This from the guy who, ignoring instructions from the White House and CIA, destroyed 92 videotapes depicting the waterboarding of detainees in CIA custody..." Pitter also wrote of the discussion around the film, "We would not even be having this debate, and this film probably would not have even been made in the way it was, had the U.S. government not gone to such great lengths over the past 11 years to cover up the tracks of its crimes and bury the facts..."[81]

National security reporter Spencer Ackerman said the film "does not present torture as a silver bullet that led to bin Laden; it presents torture as the ignorant alternative to that silver bullet".[82] Critic Glenn Kenny said that he "saw a movie that subverted a lot of expectations concerning viewer identification and empathy" and that "rather than endorsing the barbarity, the picture makes the viewer in a sense complicit with it", which is "[a] whole other can of worms".[83] Writer Andrew Sullivan said, "the movie is not an apology for torture, as so many have said, and as I have worried about. It is an exposure of torture. It removes any doubt that war criminals ran this country for seven years".[84] Filmmaker Michael Moore similarly said, "I left the movie thinking it made an incredible statement against torture", and noted that the film showed the abject brutality of torture.[85] Critic Andrew O'Hehir said that the filmmaker's position on torture in the film is ambiguous, and creative choices were made and the film poses "excellent questions for us to ask ourselves, arguably defining questions of the age, and I think the longer you look at them the thornier they get".[86]

Screenwriter Boal described the pro-torture accusations as "preposterous", stating that "it's just misreading the film to say that it shows torture leading to the information about bin Laden", while director Bigelow added: "Do I wish [torture] was not part of that history? Yes. But it was."[87] In February 2013 in The Wall Street Journal, Boal responded to the Senate critics, being quoted as saying "[D]oes that mean they can use the movie as a political platform to talk about what they've been wanting to talk about for years and years and years? Do I think that Feinstein used the movie as a publicity tool to get a conversation going about her report? I believe it, ..." referring to the intelligence committee's report on enhanced interrogations. He also said the senators' letter showed they were still concerned about public opinion supporting the effectiveness of torture and didn't want the movie reinforcing that. Boal said, though, "I don't think that [effectiveness] issue has really been resolved" if there is a suspect with possible knowledge of imminent attack who will not talk.[88]

In an interview with Time magazine, Bigelow said: "I'm proud of the movie, and I stand behind it completely. I think that it's a deeply moral movie that questions the use of force. It questions what was done in the name of finding bin Laden."[89]

Objections over the use of recordings of 9/11 victims

editAn extensive clip of the phone call to headquarters from Betty Ong, a flight attendant on one of the hijacked American Airlines planes, was used in the beginning of the film without attribution.[90] Ong's family requested that, if the film won any awards, the filmmakers apologize at the Academy Awards ceremony for using the clip without getting her heirs' consent. Her family also asked that the film's U.S. distributors make a charitable donation in Ong's name, and should go on record that the Ong family does not endorse the use of torture, which is depicted in the film during the search for Osama bin Laden.[90] Neither the filmmakers nor the U.S. distributors ever heeded any of the Ong family's requests.[91]

Mary and Frank Fetchet, parents of Brad Fetchet, who worked on the 89th floor of the World Trade Center's south tower, criticized the filmmakers for using a recording of their son's voicemail without permission. The recording has previously been heard in broadcast TV news reports and in testimony for the 9/11 Commission.[92]

See also

edit- List of films featuring the United States Navy SEALs

- Seal Team Six: The Raid on Osama Bin Laden

- No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account of the Mission that Killed Osama bin Laden

Notes

edit- ^ This is the spelling used by the film's end credits

References

edit- ^ a b c "AFI|Catalog - Zero Dark Thirty". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Zero Dark Thirty (2012)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on June 12, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "ZERO DARK THIRTY (15)". British Board of Film Classification. November 28, 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ "Zero Dark Thirty (2012) - Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ^ Child, Ben (January 6, 2012). "Kathryn Bigelow's Bin Laden film to star Joel Edgerton". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ "UPI takes territories on Kathryn Bigelow's 'Zero Dark Thirty'" Archived November 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine; Screen Daily; May 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Derschowitz, Jessica (December 11, 2012). ""Zero Dark Thirty" premieres in Los Angeles". Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c No conspiracy: New documents explain Pentagon, CIA cooperation on 'Zero Dark Thirty' Archived August 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine; Entertainment Weekly; August 28, 2012.

- ^ Bin Laden movie trailer is out; filmmakers are talking; azcentral.com; August 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c Anthony Breznican (August 6, 2012). "Bin Laden movie 'Zero Dark Thirty' shows hunt for 9/11 mastermind". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Hill, Logan (January 11, 2013). "Secrets of 'Zero Dark Thirty'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Mayer, Jane (December 18, 2014). "The Unidentified Queen of Torture". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ "The dream set". The Tribune. April 1, 2012. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Kabir Khan recreates Pakistan in Punjab for 'Phantom' - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ "Chandigarh turns Lahore". The Times of India. March 3, 2012. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ "Manimajra residents hope 'Zero Dark Thirty' will win Oscar". The Times of India. February 12, 2013. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "VHP, Shiv Sena protest against Osama film". The Times of India. March 3, 2012. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Matthias (March 7, 2012). "Hindus protest bin Laden film shoot in north India". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ "Scene location for CIA Black Site". Filmapia. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ Bergen, Peter (December 11, 2012). "'Zero Dark Thirty': Did torture really net bin Laden?". CNN. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Alexandre Desplat to Score Kathryn Bigelow's 'Zero Dark Thirty'". Film Music Reporter. Archived from the original on November 24, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ "'Zero Dark Thirty' Soundtrack Details". Film Music Reporter. December 10, 2012. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ 'Zero Dark Thirty' to be promoted in 'Medal of Honor' video game Archived September 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine; Los Angeles Times; September 10, 2012.

- ^ "Zero Dark Thirty DVD release". March 19, 2013. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ "Zero Dark Thirty Blu-ray and DVD release". March 2, 2013. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ Subers, Ray. "Weekend Report: 'Hobbit' Plummets, Holds Off Slew of Newcomers". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Chart". Entertainment Weekly. New York . January 25 – February 1, 2013. p. 102.

- ^ "Weekend Report: Controversial 'Zero Dark Thirty' Claims Top Spot". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Zero Dark Thirty (2012)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ "Zero Dark Thirty Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 26, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ Nikki Finke (January 13, 2013). "#1 'Zero Dark Thirty' Widens For $24M, 'Haunted House' Beats Disappointing 'Gangster Squad' For #2; 'Silver Linings', 'Lincoln', 'Life Of Pi' Get Oscar Bumps". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (December 17, 2012). "By Any Means Necessary: Jessica Chastain in 'Zero Dark Thirty'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Zero Dark Thirty: The Girl Who Got bin Laden". Time. November 25, 2012. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (December 14, 2012). "25 Favorites from a Year When 10 Aren't Enough". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ Denby, David (December 24, 2012). "Dead Reckoning". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 2, 2013). "Zero Dark Thirty". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ "2012 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Indiewire (December 27, 2012). "IndieWire's Editors and Bloggers Pick Their Top 10 Films of 2012 - IndieWire". www.indiewire.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Uhlich, Keith (December 13, 2012). "Keith Uhlich's Ten Best Movies of 2012". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on November 24, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ "Golden Globe winners list". USA Today. January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Allison, Graham (February 22, 2013). "'Zero Dark Thirty' has the facts wrong – and that's a problem, not just for the Oscars". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c Coll, Steve. "'Disturbing' & 'Misleading'". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ^ Nadeem F. Paracha (January 31, 2013). "Zero IQ Thirty". dawn.com.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (May 23, 2012). "WH leaks for propaganda film". Salon. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ "Barack Obama campaigns in Hollywood style". The Times of India. May 2, 2012. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ "First look at the Osama bin Laden movie" Archived 2018-08-21 at the Wayback Machine; CNN; August 7, 2012.

- ^ Hudson, John (May 17, 2012). "Is Harvey Weinstein Plotting an October Surprise for Obama?". The Atlantic Wire. Archived from the original on May 20, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Government communicated with "Zero Dark Thirty" makers"; Chicago Tribune; August 29, 2012.

- ^ "Bin Laden Movie Gets Pushed Back" Archived 2018-08-21 at the Wayback Machine; IGN Entertainment; October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Release Date of Bin Laden Film May Change" Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine; New York Times; October 19, 2011.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (November 1, 2012). "Kathryn Bigelow's 'Zero Dark Thirty' wide release delayed". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 2, 2012. [permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Bruni, Frank (December 8, 2012). "Bin Laden, Torture and Hollywood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Cohen, Roger, "Why 'Zero Dark Thirty' Works" Archived 2018-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, February 11, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ^ "Special Operators to Anti-Obama Groups: Zip It"; AP News, Navy Times; August 22, 2012.

- ^ Cieply, Michael (January 6, 2012). "Film About the Hunt for Bin Laden Leads to a Pentagon Investigation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Letter from the CIA to King re: possible leaks" Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine; House website; November 8, 2011.

- ^ Child, Ben (August 11, 2011). "Kathryn Bigelow denies White House favoritism over Bin Laden film". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ Watch, Judicial (November 15, 2012). "Obama Administration Admits Information Released to Zero Dark Thirty Filmmakers Might Pose an 'Unnecessary Security and Counterintelligence Risk' if Publicly Disclosed". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Hosenball, Mark (January 2, 2013). "Senate panel to examine CIA contacts with 'Zero Dark Thirty' filmmakers". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ Hosenball, Mark (February 25, 2013). "Senate Intelligence Committee drops bin Laden film probe". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ Zagorin, Adam, Hilzenrath, David S. (June 4, 2013). "Report: Panetta disclosed top secret info to "Zero Dark Thirty" filmmaker". POGO. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gerstein, Josh (June 5, 2013). "Leon Panetta revealed classified SEAL unit info". Politico. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (December 14, 2012). "Zero Dark Thirty: CIA hagiography, pernicious propaganda". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Fox, Jesse David (December 10, 2012). "Does Zero Dark Thirty Endorse Torture?". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Bazelon, Emily (December 11, 2012). "Does Zero Dark Thirty Advocate Torture?". Slate. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Wolff, Michael (December 24, 2012). "The truth about Zero Dark Thirty: this torture fantasy degrades us all". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ Wolf, Naomi (January 4, 2013). "A letter to Kathryn Bigelow on Zero Dark Thirty's apology for torture". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ Greenberg, Karen, J. (January 10, 2013). "Learning to Love Torture, Zero Dark Thirty-Style". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maass, Peter (December 13, 2012). "Don't Trust 'Zero Dark Thirty'". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Mayer, Jane (December 14, 2012). "ZERO CONSCIENCE IN "ZERO DARK THIRTY"". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ Mitchell, Greg (December 12, 2012). "My View: 'Zero Dark Thirty' Shows Torture Playing Key Role in Getting bin Laden". The Nation. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ Gibney, Alex (December 21, 2012). "Zero Dark Thirty's Wrong and Dangerous Conclusion". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 24, 2012. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ Slavoj Žižek (January 25, 2013). "Zero Dark Thirty: Hollywood's gift to American power". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Sen. McCain rejects torture scene in 'Zero Dark Thirty'". Entertainment Weekly. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Daunt, Tina (December 19, 2012). "Senators Call 'Zero Dark Thirty' 'Grossly Inaccurate' in Letter to Sony Pictures". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 31, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ^ Daunt, Tina (December 21, 2012). "Acting CIA Director Disputes 'Zero Dark Thirty' Accuracy in Rare Public Statement". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 22, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Denson, G. Roger (December 31, 2012). "Zero Dark Thirty Account of Torture Verified by Media Record of Legislators and CIA Officials". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Denson, G. Roger (December 25, 2012). "Zero Dark Thirty: Why the Film's Makers Should Be Defended And What Deeper bin Laden Controversy Has Been Stirred". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 25, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ^ "US: Zero Dark Thirty and the Truth About Torture | Human Rights Watch". January 11, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ "US: Zero Dark Torture | Human Rights Watch". January 11, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Ackerman, Spencer (December 10, 2012). "Two Cheers for 'Zero Dark Thirty's' Torture Scenes". Wired. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Kenny, Glenn (December 17, 2012). ""Zero Dark Thirty:" Perception, reality, perception again, and "the art defense"". Some Come Running. Archived from the original on December 25, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (December 14, 2012). "Kathryn Bigelow: Not A Torture Apologist". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Michael Moore On 'Zero Dark Thirty' & Torture: Movie Doesn't Condone Enhanced Interrogation Archived 2017-03-20 at the Wayback Machine; Huffington Post; January 25, 2013.

- ^ O'Hehir, Andrew (December 1, 2012). "Is feminism worth defending with torture?". Salon. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Pond, Steve (December 11, 2012). "'Zero Dark Thirty' Steps into the Line of Fire, Answers Critics". The Warp. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Kaminsky, Matthew, "The Art and Politics of 'Zero Dark Thirty'" Archived 2018-09-09 at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, February 15, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ Winter, Jessica (January 24, 2013). "Cover Story: Kathryn Bigelow's Art of Darkness". Time. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Michael Cieply (February 23, 2013). "9-11 victim's family raises objection to Zero Dark Thirty". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013.

The Ong family is also asking that the filmmakers donate to a charitable foundation that was set up in Ms. Ong's name. Further, they want Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is distributing Zero Dark Thirty in the United States, to include a credit for Ms. Ong and a statement on both its Web site and on home entertainment versions of the film making clear that the Ong family does not endorse torture, which is depicted in the film, an account of the search for Osama bin Laden.

- ^ Skyfall and Zero Dark Thirty Win Sound Editing: 2013 Oscars, March 5, 2013, archived from the original on February 21, 2021, retrieved April 25, 2020

- ^ "9/11 families upset over "Zero Dark Thirty" recordings". CBS News. February 25, 2013. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

Further reading

edit- "FAREED ZAKARIA GPS The Myth of America's Social Mobility; How Accurate is 'Zero Dark Thirty'?; Interview with Neil deGrasse Tyson; Internal Iranian Politics." (transcript) CNN. February 24, 2013

- Why Zero Dark Thirty divides the media in half (December 18, 2012), Alissa Quart, Reuters. "The thriller Zero Dark Thirty exposed a wide gap between film critics and their counterparts in politics."

- Schlag, Gabi (2021). "Representing torture in Zero Dark Thirty (2012): Popular culture as a site of norm contestation". Media, War & Conflict. 14 (2): 174–190. doi:10.1177/1750635219864023. S2CID 201386160.