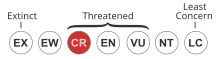

Zamia inermis is a species of plant in the family Zamiaceae. It is endemic to Actopan, Veracruz state, in eastern Mexico. It is a Critically endangered species, threatened by habitat loss to make way for farming, as well as other factors such as frequent wildfires, the possible disappearance of its pollinators, exposure to pesticides from crops, soil erosion, and being over-harvested for decorative purposes.[1]

| Zamia inermis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Zamia inermis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnospermae |

| Division: | Cycadophyta |

| Class: | Cycadopsida |

| Order: | Cycadales |

| Family: | Zamiaceae |

| Genus: | Zamia |

| Species: | Z. inermis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zamia inermis Vovides, J.D.Rees & Vázq.Torres

| |

It was estimated that there were 300-350 individuals in 2020.[1]

Description

editZamia inermis has a stem 15 to 43 centimetres (5.9 to 16.9 in) tall and 8.6 to 26.4 centimetres (3.4 to 10.4 in) in diameter, greyish in color. The stem is often branched in older plants. There are 10 to 25 compound-leaves on a crown, standing upright. Emergent leaves are light to yellowish-green. Mature leaves are 30 to 95 centimetres (12 to 37 in) long and 43.5 to 60 centimetres (17.1 to 23.6 in) wide. The petiole (stalk) is 18 to 41 centimetres (7.1 to 16.1 in) long and the leaf axis is 15 to 19 centimetres (5.9 to 7.5 in) long. Both are smooth, with no prickles. There are 27 to 32 pairs of leaflets which are linear-lanceolate in shape with smooth edges. Leaflets in the middle of the leaf are 20 to 30.5 centimetres (7.9 to 12.0 in) long and 0.9 to 1.2 centimetres (0.35 to 0.47 in) wide.[2]

Like all Zamias, Zamia inermis is dioecious, with each plant being either male or female. There are usually one or two, sometimes up to six, male strobili (cones) on a plant. They are cylindrical, upright, up to 9.1 centimetres (3.6 in) long, up to 2.8 centimetres (1.1 in) in diameter, and beige-yellowish in color. They sit on peduncles (stalks) that are up to 4.5 centimetres (1.8 in) tall, covered with thick light-yellow hairs. There are usually one or two female cones on a plant, which are erect, cylindrical, 13 to 23 centimetres (5.1 to 9.1 in) tall, 8 to 9.8 centimetres (3.1 to 3.9 in) in diameter, and covered with light-brown to beige hairs. The female cones sit on peduncles that are 6 to 8 centimetres (2.4 to 3.1 in) long, 1.2 to 1.4 centimetres (0.47 to 0.55 in) in diameter, and covered with brown hairs. Seeds are ovoid, 1.7 to 2.5 centimetres (0.67 to 0.98 in) long and 1.4 to 2.1 centimetres (0.55 to 0.83 in) in diameter. The sarcotesta (pulpy seed coat) is smooth, starting pink and turning red when mature. The chromosome number is 2n=16.[3][4]

The species name inermis refers to the complete lack of prickles on the leaves.[5]

Zamia inermis is part of the Fischeri clade.

Habitat and distribution

editZamia inermis originally grew in deciduous tropical dry forests, primarily inhabiting steep slopes located in low mountainous regions at altitudes ranging from 200 to 300 meters. The plants grow in thin, arid volcanic soils with limited organic content, adapting to the challenges of such environments. Their presence is not confined to level ground, as they also grow on steep slopes within their designated habitat.[1]

Zamia inermis is endemic to central Veracruz state. The known natural population is found in small, scattered patches making up three sub-populations on two hills within a 9.7 square kilometres (3.7 sq mi) area.[6] In 2017, the wild population was reported to consist of 654 plants. Only 63 seedlings appeared over the three years up to 2017, 80% of which died.[7]

Threats

editThe well-being of Zamia inermis is significantly influenced by a range of factors including habitat degradation due to agricultural expansion, frequent and excessive wildfires, the potential extinction of essential pollinators, crop-spraying activities, soil erosion, and the excessive collection of individuals for ornamental use. These combined factors pose notable challenges to the species' survival and population sustainability.[1]

The natural pollinator of Zamia inermis, a beetle, may have been much reduced in population or exterminated in the area in which the plant grows wild. As is typical in cycads, the beetles that pollinate the species live in and feed on male pollen cones. The diapause larval stage of the beetle spends the winter in cones that have fallen off and become part of the litter surrounding the plants. All of the known wild population of Z. inermis is on a private ranch, and the land is periodically burned for clearance and weed control, consuming the litter. Another cause for loss of pollinators may be the application of pesticides to neighboring fields. As a result of the loss of the beetle population, the population of Z. inermis is falling. It is popular as an ornamental plant, and is being propagated in commercial nurseries in the United States and Mexico. Seed production in the wild plants is very poor, and few of the seeds that are produced are viable. On the other hand, seed production in Z. inermis plants in gardens and nurseries, when hand-pollinated, is robust, with almost 100% germination.[8][9]

Zamia inermis lost 75% of its population in the 50 years up to 2017. A study that year found a low genetic diversity in the only known wild population of the species. Plants grown in a nursery from seeds collected from wild plants five years earlier showed significantly less genetic diversity than the wild population, likely due, in part, to the fact that those plants were grown from seeds from just five viable cones.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Bösenberg, J.D. (2023) [errata version of 2022 assessment]. "Zamia inermis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2024 (2): e.T42111A69833031. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ Nicolalde-Morejón, Vovides & Stevenson 2009, p. 313.

- ^ Nicolalde-Morejón, Vovides & Stevenson 2009, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Octavio-Aguilar et al. 2017, p. 788.

- ^ Nicolalde-Morejón, Vovides & Stevenson 2009, p. 314.

- ^ Octavio-Aguilar et al. 2017, p. 789.

- ^ Iglesias-Andreu et al. 2017, p. 716.

- ^ Octavio-Aguilar et al. 2017, pp. 788, 793.

- ^ Iglesias-Andreu et al. 2017, p. 715.

- ^ Iglesias-Andreu et al. 2017, pp. 715, 720.

Sources

edit- Octavio-Aguilar, Pablo; Rivera-Fernández, Andrés; Iglesias-Andreu, Lourdes Georgina; Vovides, P. Andrew; de Cáceres-González, Francisco F. Núñez (April 2017). "Extinction risk of Zamia inermis: a demographic study in its single natural population". Biodiversity and Conservation. 26 (4): 787–800. doi:10.1007/s10531-016-1270-z. ISSN 1572-9710.

- Iglesias-Andreu, Lourdes G.; Octavio-Aguilar, Pablo; Vovides, Andrew P.; Meerow, Alan W.; de Cáceres-González, Francisco N.; Galván-Hernández, Dulce María (November–December 2017). "Extinction Risk of Zamia inermis (Zamiaceae): A Genetic Approach for the Conservation of Its Single Natural Population". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 178 (9): 715–723. doi:10.1086/694080. ISSN 1058-5893.

- Nicolalde-Morejón, Fernando; Vovides, Andrew P.; Stevenson, Dennis W. (December 2009). "Taxonomic revision of Zamia in Mega-Mexico". Brittonia. 61 (4): 301–335. doi:10.1007/s12228-009-9077-9. ISSN 1938-436X.