Yixianornis (meaning "Yixian Formation bird"[1]) is a bird genus from the early Cretaceous period. Its remains have been found in the Jiufotang Formation at Chaoyang (People's Republic of China) dated to the early Aptian age, around 120 million years ago.[2] Only one species, Yixianornis grabaui, is known at present. The specific name, grabaui, is named after American paleontologist Amadeus William Grabau, who surveyed China in the early 20th century.

| Yixianornis Temporal range: Early Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

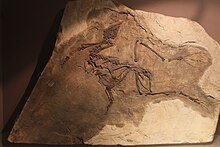

| Type specimen, Paleozoological Museum of China | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Avialae |

| Family: | †Songlingornithidae |

| Genus: | †Yixianornis |

| Species: | †Y. grabaui

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Yixianornis grabaui Zhou & Zhang, 2001

| |

Description

editThe type specimen (and only specimen found to date) of Yixianornis, catalog number IVPP V12631 in the collections of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, is one of the most well-preserved bird fossils known from the Jehol group. It is nearly complete and, unlike many other fossils, the bones are mostly uncrushed and were not split in half when the stone slabs were initially separated. It is also one of the few known Mesozoic ornithuran bird specimens that preserve clear impressions of the wing and tail feathers.[3]

Yixianornis was moderately sized compared to other yanornithiformes, at about the size of a chicken. IVPP V12631 was measured approximately 19 to 20 centimetres (7.5 to 7.9 in) long (excluding feathers),[1][4] 11.5 centimetres (4.5 in) tall at the hips,[4] with a wingspan of about 40 cm (16 in).[3] Its body weight has been estimated to have been 200 to 350 grams (0.44 to 0.77 lb).[4][5] Yixianornis was grossly similar to its close relatives Yanornis and Songlingornis. All three had teeth, though in Yixianornis the tips of the jaws were toothless and pockmarked with small pits and grooves, possibly indicating the presence of a beak. The teeth were small and peg-like, and lacked any serrations. The lower jaw was thin and delicate.[3]

The breastbone bore a strong keel for the attachment of flight muscles, and contained a distinct opening or fenestra, a unique characteristic of yanornithiformes. The upper and lower arm were about the same length. Like other ornithurines, Yixianornis had a highly fused hand, with many wrist bones joined that are free in more primitive birds.[3]

The hips and hind limbs preserved more primitive features than the forelimbs, supporting the idea that the modern adaptations in the locomotion seen in modern birds evolved after the many specializations needed for flight. The hallux, or reversed, perching toe of modern birds, is noticeably pointed backward in the fossil. However, there is no clear evidence that the bone itself was twisted, which would indicate that the toe was permanently reversed.[3]

Yixianornis differed from related birds only in small skeletal characteristics. For example, the teeth in the lower jaw of Yixianornis were confined to a smaller space, while they lined more of the jaw in related species. The wishbone (furcula) of Yixianornis was more narrow than in its relatives, and its shoulder blade was much shorter, only half the length of the upper arm bone (humerus).[3]

The flight feathers of Yixianornis are well preserved in the only known specimen. There were about five primary feathers on each wing, the longest measuring about 6.7 cm (2.6 in). Unlike in many more basal species, the feathers did not become narrower or more pointed at the tip. Rather, the feathers were very broad and rounded. There were eight tail feathers, up to 9.2 cm (3.6 in) long, anchored to a pygostyle and rectrical bulb (see below) as in modern birds.[3]

Biology and ecology

editThe feathers of Yixianornis are unique among those preserved in other Mesozoic bird specimens, and have allowed scientists to infer its probable lifestyle. The wings were broad and rounded, with similarly large, rounded feathers. The tail feathers were arranged in a graduated series, with the outer feathers anchored closer to the base of the tail. This would have given the tail a slightly rounded silhouette. Additionally, carbonized tissue impressions show that it had a rectrical bulb, the muscles around the tail which allow the tail feathers to be fanned out during flight, and retraced when at rest.[3]

These adaptations are rare among Mesozoic birds, many of which are known to have had long, pointed wings and very few, if any, long tail feathers. The rectrical bulb and plough-shaped pygostyle allowing for tail fanning is also a unique characteristic of ornithurine birds, of which Yixianornis is among the earliest known.[3] In a 2006 study, Julia Clarke, Zhou Zhonghe and Zhang Fucheng found that the ability to fan the tail, along with the broad wings, show that it probably preferred environments with dense vegetation, where high maneuverability in flight would be necessary.[3]

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Yixianornis and modern birds and reptiles indicate that it may have been diurnal, similar to most modern birds.[6]

Classification

editIt was a close relative of Yanornis and together with this and Songlingornis forms a clade of early modern birds. Clarke et al. found that Yixianornis was the most primitive bird to display an essentially modern pygostyle and fan of tail feathers.[7] Later, an enantiornithine called Shanweiniao was found to have a fan tail as well, though it may have evolved independently of modern birds.[8]

References

edit- ^ a b Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2022.

Winter 2011 Appendix

- ^ He, H.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Zhou, Z.H.; Wang, F.; Boven, A.; Shi, G.H.; Zhu, R.X. (2004). "Timing of the Jiufotang Formation (Jehol Group) in Liaoning, northeastern China, and its implications". Geophysical Research Letters. 31 (13): 1709. Bibcode:2004GeoRL..3112605H. doi:10.1029/2004GL019790.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Clarke, J.A.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. (2006). "Insight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui". Journal of Anatomy. 208 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00534.x. PMC 2100246. PMID 16533313.

- ^ a b c Molina-Pérez, R.; Larramendi, A. (2019). Dinosaurs Facts and Figures: The Theropods and Other Dinosauriformes. Princeton University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-691-18031-1.

- ^ Xu, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, R.; Dong, L.; Lin, M.; Xu, X.; Tang, J.; You, H.; Zhou, G.; Wang, L.; He, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Z. (2023). "A new avialan theropod from an emerging Jurassic terrestrial fauna". Nature. 621 (7978): 336–343. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06513-7. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407.

- ^ Clarke, Julia A.; Zhou, Zhonghe; Zhang, Fucheng (2006). "Insight into the evolution of avian flight from a new clade of Early Cretaceous ornithurines from China and the morphology of Yixianornis grabaui". Journal of Anatomy. 208 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00534.x. PMC 2100246. PMID 16533313.

- ^ Jingmai K. O’connor, Xuri Wang, Luis M. Chiappe, Chunling Gao, Qingjin Meng,Xiaodong Cheng, And Jinyuan Liu (2009). "Phylogenetic support for a specialized clade of Cretaceous enantiornithine birds with information from a new species" Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(1):188–204, March 2009# 2009 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

- Mortimer, Michael (2004): The Theropod Database: Phylogeny of taxa. Retrieved 2013-MAR-02.