The yellow brick road is a central element in the 1900 children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by American author L. Frank Baum. The road also appears in the several sequel Oz books such as The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) and The Patchwork Girl of Oz (1913).

| Yellow brick road | |

|---|---|

| The Oz series location | |

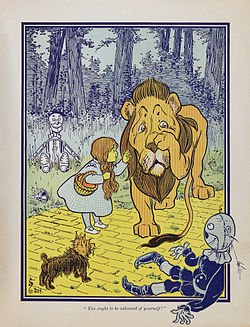

Dorothy and her companions befriend the Cowardly Lion, while traveling on the yellow brick road--illustration by W. W. Denslow (1900). | |

| Created by | L. Frank Baum |

| Genre | Classics children's books |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Road paved with yellow bricks, leading to its destination--Emerald City |

The road's most notable depiction is in the classic 1939 MGM musical film The Wizard of Oz, loosely based on Baum's first Oz book. In the novel's first edition, the road is mostly referred to as the "Road of Yellow Bricks". In the original story and in later films based on it such as The Wiz (1978), Dorothy Gale must find the road before embarking on her journey, as the tornado did not deposit her farmhouse directly in front of it as in the 1939 film.

Road's history

editThe following is an excerpt from the third chapter of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, in which Dorothy sets off to see the Wizard:

There were several roads nearby, but it did not take Dorothy long to find the one paved with yellow bricks. Within a short time, she was walking briskly toward the Emerald City; her Silver Shoes tinkling merrily on the hard, yellow roadbed.

The road is first introduced in the third chapter of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The road begins in the heart of the eastern quadrant called Munchkin Country in the Land of Oz. and leads to the imperial capital of Oz, Emerald City, which is located in the exact center of the continent. The book's protagonist Dorothy is forced to search for the road before she can begin her quest to seek the Wizard, eventually finding out after meeting with the Munchkins and the Good Witch of the North. Later in the book, Dorothy and her companions, the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman and Cowardly Lion discover that the road has fallen into disrepair in some parts of the land, having several broken chasms ending at dangerous cliffs with deadly drops. At the end of the book, Dorothy learns that neither Emerald City nor the yellow brick road existed prior to Oz's arrival. When Oscar Diggs arrived in Oz via hot-air balloon that had been swept away in a storm, the people of the land were convinced he was a great "Wizard" who had finally come to fulfill a long-awaited prophecy. In the power vacuum left by the recent fall of Oz's mortal King Pastoria and the mysterious disappearance of his baby daughter Princess Ozma, Diggs immediately proclaimed himself as Oz's new dominant ruler and had his people build the road as well as the city in his honor.

In the second Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz, Tip and his companion Jack Pumpkinhead likewise follow a yellow brick road to reach Emerald City while traveling from Oz's northern quadrant, the Gillikin Country.[1] In the book The Patchwork Girl of Oz, it is revealed that there are two yellow brick roads from Munchkin Country to the Emerald City: according to the Shaggy Man, Dorothy took the longer and more dangerous one in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[1]

In the 1939 film, a red brick road can be seen intertwined with the yellow brick road, both spiraling out from the same point but leading in different directions. In the 1985 film Return to Oz, Dorothy returns to Oz long after being sent back home to Kansas from her first visit; she finds the yellow brick road in ruins by the hands of the evil Nome King who also conquered the Emerald City. She defeats him and the city is restored to its original glory, and presumably the road is as well.

Real yellow brick roads

editThere are various accounts of what inspired the yellow brick road. One account says it is a brick road in Peekskill, New York, where L. Frank Baum attended Peekskill Military Academy.[2] Other accounts say it was inspired by a road paved with yellow bricks near Holland, Michigan, where Baum spent summers.[3] Ithaca, New York, also makes a claim for being Frank Baum's inspiration. He opened a road tour of his musical, The Maid of Arran, in Ithaca, and he met his future wife Maud Gage Baum while she was attending Cornell University. At the time, yellow bricks paved local roads.[4] Portions of U.S. Route 54 within the state of Kansas have been designated "the yellow brick road".[5] Dallas, Texas makes a claim that Baum once stayed at a downtown hotel during his newspaper career (located near what is now the Triple Underpass) at a time when the streets were paved with wooden blocks of Bois D'Arc also known as Osage Orange. Supposedly, after a rainstorm the sun came out and he saw a bright yellow brick road from the window of his room.[citation needed]

Two direct, published references to the origin of the yellow brick road came from Baum's own descendants: his son Frank Joslyn Baum in To Please A Child and the other by Roger S. Baum, the great-grandson of L. Frank Baum who stated, "Most people don't realize that the Wizard of Oz was written in Chicago, and the Yellow Brick Road was named after winding cobblestone roads in Holland, Michigan, where great-grandfather spent vacations with his family."

The Vision Oz Fund was established in November 2009 to raise funds that will be used to help increase the awareness, enhancement, and further development of Oz-related attractions and assets in Wamego, Kansas. The first fundraiser is under way and includes selling personalized engraved yellow bricks, which will become part of the permanent walkway (aka "The Yellow Brick Road") in downtown Wamego.[6]

In 2019, a commemorative yellow brick road was installed in Chicago's Humboldt Park at the site of L. Frank Baum's 1899 residence.[7]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b L. Frank Baum, Michael Patrick Hearn, The Annotated Wizard of Oz, p 107, ISBN 0-517-50086-8

- ^ Banjo, Shelly (31 May 2011). "Historian Believes if You Follow the Yellow Brick Road, You End Up in Peekskill". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Castanier, Bill (13 June 2019). "Holland honors 'Wizard of Oz' author despite controversy". City Pulse. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "Facts & Trivia About Ithaca". VisitIthaca.com. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "K.S.A. 68-1029". Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Wamego Community Foundation". Thewcf.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Bloom, Mina (4 November 2019). "Yellow Brick Road Built Where L. Frank Baum Wrote 'Wizard Of Oz,' Delighting Humboldt Park Residents". Block Club Chicago. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

Further reading

edit- Dighe, Ranjit S. ed. The Historian's Wizard of Oz: Reading L. Frank Baum's Classic as a Political and Monetary Allegory (2002)

- Hearn, Michael Patrick (ed). (2000, 1973) The Annotated Wizard of Oz. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-04992-2

- Ritter, Gretchen. "Silver slippers and a golden cap: L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and historical memory in American politics." Journal of American Studies (August 1997) vol. 31, no. 2, 171–203. online at JSTOR

- Rockoff, Hugh. "The 'Wizard of Oz' as a Monetary Allegory," Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 739-60 online at JSTOR