This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Contains unidentified or uninterpreted Chinese characters. (July 2022) |

The Yellow River Map, Scheme, or Diagram, also known by its Chinese name as the Hetu, is an ancient Chinese diagram that appears in myths concerning the invention of writing by Cangjie and other culture heroes. It is usually paired with the Luoshu Square—named in reference to the Yellow River's Luo tributary—and used with the Luoshu in various contexts involving Chinese geomancy, numerology, philosophy, and early natural science.[1]

| Yellow River Map (Hetu) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 河圖 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 河图 | ||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Hétú | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | River Diagram/Picture | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Geographical background

editThe Yellow River (Chinese: Huang He) flows from the Tibetan Plateau to the Bay of Bohai over a course of 5,464 kilometers (3,395 mi), making it the second-longest river in Asia and the sixth-longest in the world. Its ancient name was simply He before that character was broadened to be used in reference to most moderately sized rivers. The River Map has thus always been understood to be particularly in reference to the Yellow River and sometimes taken as a diagram of its course or the forces acting upon it.[citation needed]

Astrological background

editThe concept of the Yellow River Map has a contextual apparatus associated with ancient Chinese cosmology. Various myths or legends are connected with the idea of mapping, involving correspondences between the earth, the sky, and/or abstract diagrams. The idea of a simple division of a flat/square earth into the very basic 3x3, (9-square) grid is historically attested in literature as early as the Tian Wen's "Heavenly Questions", together with a suggested corresponding mapping solution for a round heaven/the sky (Hawkes, 136–137 [notes to Tian wen]). This text from the Chu Ci dates to pre-221 BCE. This basic grid is associated with the plan of Yu to control the Great Flood of China.[2]

Legendary accounts

editMyths of the Yellow River Map go back to earliest stages of the recorded history of Chinese culture.

Fu Xi

editFu Xi or Fuxi was a half-snake deity and protoplast who has appeared with his sister Nüwa in accounts of the creation of humanity and invention of civilization since at least the Zhou dynasty. Among the stories told about him is one in which, inspired by spider webs and other natural phenomena,[3] he created the River Map and then used it to devise the trigrams that comprise the later I Ching.

Great Flood

editYellow River floods were a constant occurrence throughout ancient, medieval, and early modern Chinese history, sometimes covering entire provinces and even shifting between the north and south sides of the Shandong Peninsula. The Great Flood was a foundational myth of Chinese culture concerning a major flood said to have lasted at least two generations amid storms and famines. Chinese legend traditionally places it during the third millennium BCE reign of the Emperor Yao. The River Map typically plays an important role in Yu the Great's eventual successful control over the flooding waters c. 2200–2100 BCE.[citation needed]

He Bo

editThe personification or deity of the Yellow River holds the rank of count or earl (bo) in the celestial bureaucracy and is accordingly known as He Bo. In some accounts, he is involved in providing the River Map.[citation needed]

Houtu

editHoutu (后土) is a male, female, or non-gendered divinity depending on the source, although the image of a Sacred Mother Earth deity is now common. Houtu is worshiped in Chinese popular religion, with her birthday on the 18 day of the third month of the Chinese lunar calendar. Sacrifice and prayer to Houtu are believed to be efficacious for problems of weather, reproduction and family, wealth, and boating safety on the Yellow River.[4] According to one account, when Yu the Great was attempting to channel the Yellow River and so avoid its flooding, he began by trying to open it to the west towards the mountains and away from the sea. Observing this, Houtu is said to have created and studied the River Map, after which she sent divine messenger birds to Yu to tell him to open up the river to the east instead. Yu's new dredging was a success, the flood waters drained into the eastern sea, and Yu's former dredging project toward the west was named the "River Wrongly Opened".[5] In this story, Houtu and the River Map were key to the successful engineering solution to the flood problem.

Historical evidence

editThe River Map is attested to in the Gu Ming section of the Book of Documents, one of its "new text" sections. Supposedly, the River Map was put on display during the Zhou dynasty. However, this has also been interpreted to mean a depiction of the 8 trigrams (bagua).[6] This incident is recorded to have been during the reign of the Zhou Kangwang, who reigned either about 1020–996 BCE or 1005–978 BCE.

Literature

editInterpretation

editInterpretation

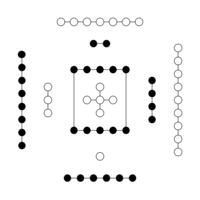

editOne way of analyzing the Yellow River Map is by comparison with the Luoshu. Wolfram Eberhard says that the River Plan is proven "beyond a reasonable doubt" to be a magic square.[7] He connects it to the mingtang halls of worship, saying that they share a division into 9 fields: these in turn are correlated with the 9 celestial objects—the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Mars, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Rahu, and Ketu—introduced from and according to Indian astronomy. Other sources emphasize these points for the Luoshu. Another interpretation of the River Diagram has to do with the 5 elements (wuxing) and the 5 Asian cardinal directions. Anyway, according to James Legge the earliest versions appear to no longer be extant, with received versions going back only to Song dynasty (early Twelfth Century); concluding, "If we had the original form of 'the River Map,' we should probably find it a numerical trifle, not more difficult, not more supernatural, than the Lo Shu Magic Square",[8] a companion piece to the River Map. Nevertheless, Legge finds it of interest in interpreting the I Ching.

First of all, Legge notes that the little bright circles of the "Map" correspond with the "whole" (yang) lines of the I Ching and that the little dark circles of the "Map" correspond with the "divided" (yin) lines thereof.[9]

Tables

edit| fire (火) 7 (extinction) 2(generation) |

||

| wood (木) 8 (extinction) 3 (generation) |

earth (土) 5 (generation) 10(extinction) |

metal (金) 4 (generation) 9 (extinction) |

| 1 (generation) 6 (extinction) water (水) |

- Notes:

- Extinction is: 成數, which could also be translated as "completion".

- Generation is: 生數, which could also be translated as "birth".

- 10 is represented in the Chinese (as are the other numerals) with a (different) single character: 十.

Cardinal directions [citation needed]

editOdd number order (1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

edit| x | 7(west, 西) | x |

| 3(south, 南) | 5(center, 中) | 9(north, 北) |

| x | 1(east, 東) | x |

Even number order (2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

edit| x | 2(west, 西) | x |

| 8(north, 北) | 10(center, 中) | 4(south, 南) |

| x | 6(east, 東) | x |

Places

editCertain places in modern China use Hétú (河图) as part of their proper place names. These include 河图镇 (岳西县), 河图镇 (保山市), and 河图乡.

See also

edit- Longma, dragon-horse creature, mythological delivery beast of the Yellow River Map

- Luo River (Henan)

- Luoshu Square

- Mount Buzhou, an important geographic feature, in relevant mythology

References

edit- ^ a b Wu 1982, p. 52.

- ^ Hawkes 2011, p. 139.

- ^ Yang & An 2005, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Yang & An 2005, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Yang & An 2005, p. 137.

- ^ Wu 1982, pp. 52–53 & 102.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram, "Square", Dictionary of Chinese Symbols, p. 276.

- ^ Legge 1963, pp. xv–xviii.

- ^ Legge 1963, p. xvi.

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (2003 [1986 (German version 1983)]), A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00228-1

- Hawkes, David (2011) [1985]. The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2.

- The I Ching: The Book of Changes. Translated by Legge, James (Second ed.). New York: Dover. 1963 [1899]. LCCN 63-19508.

- Wu, K. C. (1982). The Chinese Heritage. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54475X.

- Yang, Lihui; An, Deming (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6.