The wild yak (Bos mutus) is a large, wild bovine native to the Himalayas. It is the ancestor of the domestic yak (Bos grunniens).

| Wild yak Temporal range: Early Pliocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Stuffed specimen in the ANSP, Pennsylvania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bos |

| Species: | B. mutus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bos mutus Przewalski, 1883

| |

| |

| Distribution of wild yak | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editThe ancestor of the wild and domestic yak is thought to have diverged from Bos primigenius at a point between one and five million years ago.[2] The wild yak is now normally treated as a separate species from the domestic yak (Bos grunniens).[3] Based on genomic evidence, the closest relatives of yaks are considered to be bison, which have historically been considered members of their own titular genus, rendering the genus Bos paraphyletic.[4]

Relationships of members of the genus Bos based on nuclear genomes after Sinding, et al. 2021.[5]

| Bos |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

editThe wild yak is among the largest extant bovid species. Adults stand about 1.6 to 2.05 m (5.2 to 6.7 ft) tall at the shoulder, and weigh 500–1,200 kg (1,100–2,600 lb). The head and body length is 2.4 to 3.8 m (7.9 to 12 ft), not counting the tail of 60 to 100 cm (24 to 39 in).[6] The females are about one-third the weight and are about 30% smaller in their linear dimensions when compared to bull wild yaks. Domesticated yaks are somewhat smaller.[7][8][9][10]

They are heavily built animals with a bulky frame, sturdy legs, and rounded cloven hooves. To protect against the cold, the udder in females and the scrotum in males are small, and covered in a layer of hair. Females have four teats. Both sexes have long shaggy hair, with a dense woolly undercoat over the chest, flanks, and thighs for insulation against the cold. In males especially, this undercoat may form a long "skirt" that can reach the ground. The tail is long and horse-like, rather than tufted like the tails of cattle or bison. The coat is typically black or dark brown, covering most of the body, with a grey muzzle (although some wild golden-brown individuals have been reported). Wild yaks with gold coloured hair are known as the wild golden yak (Chinese: 金色野牦牛; pinyin: jīnsèyě máoniú). They are considered an endangered subspecies in China, with an estimated population of 170 left in the wild.[11]

Two morphological types have been identified, so-called Qilian and Kunlun.[6]

Distribution and habitat

editWild yaks once ranged up to southern Siberia to the east of Lake Baikal,[12] with fossil remains of them being recovered from Denisova Cave,[13] but became extinct in Russia around the 17th century.[14] Today, wild yaks are found primarily in northern Tibet and western Qinghai, with some populations extending into the southernmost parts of Xinjiang, and into Ladakh in India. Small, isolated populations of wild yak are also found farther afield, primarily in western Tibet and eastern Qinghai. In historic times, wild yaks were also found in Bhutan, but they are now considered extinct there.[1]

The primary habitat of wild yaks consists of treeless uplands between 3,000 and 5,500 m (9,800 and 18,000 ft), dominated by mountains and plateaus. They are most commonly found in alpine tundra with a relatively thick carpet of grasses and sedges rather than the more barren steppe country.[15]

The wild yak was thought to be regionally extinct in Nepal in the 1970s, but was rediscovered in Humla in 2014.[16][17] This discovery later made the species to be painted on Nepal's currency.[18]

Behaviour and ecology

editThe diet of wild yaks consists largely of grasses and sedges, such as Carex, Stipa, and Kobresia. They also eat a smaller amount of herbs, winterfat shrubs, and mosses, and have even been reported to eat lichen. Historically, the main natural predator of the wild yak has been the Himalayan wolf, but Himalayan black bears, Himalayan brown bears and snow leopards have also been reported as predators in some areas, likely of young or infirm wild yaks.[11]

Thubten Jigme Norbu, the elder brother of the 14th Dalai Lama, reported on his journey from Kumbum in Amdo to Lhasa in 1950:

Before long I was to see the vast herds of drongs with my own eyes. The sight of those beautiful and powerful beasts who from time immemorial have made their home on Tibet's high and barren plateaux never ceased to fascinate me. Somehow these shy creatures manage to sustain themselves on the stunted grass roots which is all that nature provides in those parts. And what a wonderful sight it is to see a great herd of them plunging head down in a wild gallop across the steppes. The earth shakes under their heels and a vast cloud of dust marks their passage. At nights they will protect themselves from the cold by huddling up together, with the calves in the centre. They will stand like this in a snow-storm, pressed so close together that the condensation from their breath rises into the air like a column of steam. The nomads have occasionally tried to bring up young drongs as domestic animals, but they have never entirely succeeded. Somehow once they live together with human beings they seem to lose their astonishing strength and powers of endurance; and they are no use at all as pack animals, because their backs immediately get sore. Their immemorial relationship with humans has therefore remained that of game and hunter, for their flesh is very tasty.

— Thubten Norbu, Tibet is My Country[19]

Wild yaks are herd animals. Herds can contain several hundred individuals, although many are much smaller. Herds consist primarily of females and their young, with a smaller number of adult males. On average female yaks graze 100m higher than males. Females with young tend to choose grazing ground on high, steep slopes.[20] The remaining males are either solitary, or found in much smaller groups, averaging around six individuals. Groups move into lower altitude ranges during the winter.[1] Although wild yaks can become aggressive when defending young, or during the rut, they generally avoid humans, and may flee for great distances if approached.[11]

Reproduction

editWild yaks mate in summer and give birth to a single calf the following spring.[21] Females typically only give birth every other year.[11]

Conservation

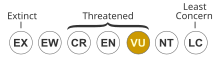

editThe wild yak is currently listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. It was previously classified as Endangered, but was downlisted in 1996 based on the estimated rate of population decline and current population sizes. The latest assessment in 2008 suggested a total population of no more than 10,000 mature individuals.[1]

The wild yak is experiencing threats applied by several sources. Poaching, including commercial poaching, has remained the most serious threat; males are particularly affected because of their more solitary habits. Disturbance by and interbreeding with livestock herds is also common. This may include the transmission of cattle-borne diseases, although no direct evidence of this has yet been found. Conflicts with herders themselves, as in preventive and retaliatory killings for abduction of domestic yaks by wild herds, also occur but appear to be relatively rare. Recent protection from poaching particularly appears to have stabilized or even increased population sizes in several areas, leading to the IUCN downlisting in 2008. In both China and India, the species is officially protected; in China it is present in a number of large nature reserves.[1]

Impact on humans

editThe wild yak is a reservoir for zoonotic diseases of both bacterial and viral origins. Such bacterial diseases include anthrax, botulism, tetanus, and tuberculosis.[22]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Buzzard, P. & Berger, J. (2016). "Bos mutus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T2892A101293528. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T2892A101293528.en. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Guo, S.; et al. (2006). "Taxonomic placement and origin of yaks: implications from analyses of mtDNA D-loop fragment sequences". Acta Theriologica Sinica. 26 (4): 325–330. Archived from the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (2003). "Opinion 2027. Usage of 17 specific names based on wild species which are predated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): conserved". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 60: 81–84. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Wang, Kun; Lenstra, Johannes A.; Liu, Liang; Hu, Quanjun; Ma, Tao; Qiu, Qiang; Liu, Jianquan (19 October 2018). "Incomplete lineage sorting rather than hybridization explains the inconsistent phylogeny of the wisent". Communications Biology. 1: 169. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0176-6. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6195592. PMID 30374461.

- ^ Sinding, M.-H. S.; Ciucani, M. M.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Carmagnini, A.; Rasmussen, J. A.; Feng, S.; Chen, G.; Vieira, F. G.; Mattiangeli, V.; Ganjoo, R. K.; Larson, G.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Petersen, B.; Frantz, L.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2021). "Kouprey (Bos sauveli) genomes unveil polytomic origin of wild Asian Bos". iScience. 24 (11): 103226. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j3226S. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.103226. PMC 8531564. PMID 34712923.

- ^ a b Han Jianlin, M. Melletti, J. Burton, 2014, Wild yak (Bos mutus Przewalski, 1883), Ecology, Evolution and Behavior of Wild Cattle: Implications for Conservation, Chapter 1, p.203, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Nowak, R. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World, 6th Edition, Volume II. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press (quoted in Oliphant, M. 2003. "Bos grunniens" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed 4 April 2009 Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Boitani, Luigi (1984). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Mammals. Simon & Schuster/Touchstone Books, ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1

- ^ "Bos grunniens (Linnaeus). zsienvis.nic.in". Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Wild yak photo – Bos mutus – G13952 . ARKive. Retrieved on 19 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Leslie, D.M.; Schaller, G.B. (2009). "Bos grunniens and Bos mutus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)". Mammalian Species. 836: 1–17. doi:10.1644/836.1.

- ^ Stanley J. Olsen, 1990, Fossil Ancestry of the Yak, Its Cultural Significance and Domestication in Tibet, p.75, Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

- ^ Puzachenko, A.Yu.; Titov, V.V.; Kosintsev, P.A. (20 December 2021). "Evolution of the European regional large mammals assemblages in the end of the Middle Pleistocene – The first half of the Late Pleistocene (MIS 6–MIS 4)". Quaternary International. 605–606: 155–191. Bibcode:2021QuInt.605..155P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.08.038. Retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Daniel J Miller, Gui Quan. Cai, Richard B. Harris, 1994, Wild yaks and their conservation on the Tibetan plateau, Ecology, Evolution and Behavior of Wild Cattle: Implications for Conservation, Chapter 12, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Schaller, G.B.; Liu, W. (1996). "Distribution, status, and conservation of wild yak Bos grunniens". Biological Conservation. 76 (1): 1–8. Bibcode:1996BCons..76....1S. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(96)85972-6.

- ^ "Extinct Wild Yak found in Nepal". 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Raju Acharya, Yadav Ghimirey, Geraldine Werhahn, Naresh Kusi, Bidhan Adhikary, Binod Kunwar, 2015, Wild yak Bos mutus in Nepal: rediscovery of a flagship species

- ^ Josua Learn, 2019, Snapping the Yak: How an Iconic Photo Ended Up on Nepal's Currency Archived 11 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tibet is My Country: Autobiography of Thubten Jigme Norbu, Brother of the Dalai Lama as told to Heinrich Harrer, p. 151. First published in German in 1960. English translation by Edward Fitzgerald, published 1960. Reprint, with updated new chapter, (1986). Wisdom Publications, London. ISBN 0-86171-045-2.

- ^ Berger, J.; Cheng, E.; Kang, A.; Krebs, M.; Li, L.; Lu, Z.X.; Buqiong; B.; Schaller, G.B. (2014). "Sex differences in ecology of wild yaks at high elevation in the Kekexili Reserve, Tibetan Qinghai Plateau, China". Journal of Mammalogy. 95 (3): 638–645. doi:10.1644/13-MAMM-A-154.

- ^ Wiener, G.; Jianlin, H.; Ruijun, L. (2003). "4 The Yak in Relation to Its Environment" Archived 1 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Yak, Second Edition. Bangkok: Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ISBN 92-5-104965-3. Accessed 8 August 2008.

- ^ Dubal, Z; Khan, M. H.; Dubal, P. B. (2013). "Bacterial and Viral Zoonotic Diseases of Yak" (PDF). International Journal of Bio-resource and Stress Management. 4 (2): 288–292. S2CID 51834203. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.