Wikipedia:WikiProject Military history/News/January 2016/Op-ed

|

Over Our Dead Bodies, Apparently |

- By TomStar81

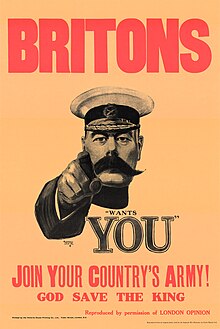

In January 1916, the British Empire reevaluated the state of the war, comparing military requirements and the size of its armed forces. It came to a conclusion that would alter the home front for the remainder of the war. Determining that since the outbreak of the war on mainland Europe the Empire had been bled sufficiently to require more troops, but finding that volunteers for the military had dropped off since hostilities had commenced some 18 months earlier, the Ministry of Defence introduced the Derby Scheme to entice personnel to enlist and serve in the UK. By January 1916 even this measure could not keep up with the demand for new soldiers. Consequently, Parliament passed the Military Service Act 1916 and, in so doing, introduced conscription for the war effort.

Conscription has been practiced by virtually every nation or region to have existed on the earth. In ancient times, conscription would have been inevitable, as cavemen and others who lived in societies that were either highly mobile or highly at risk no doubt relied on the whole of its parts for defensive and offensive capabilities. As societies evolved, so to did the concept of military service. For some in classical times, the military was seen as a way to escape trouble; for others, a route to glory; and in some cases such as Sparta the military was so much ingrained into the society that the two merged to form an almost indistinguishable hybrid. As time went on through the Dark Ages and into the Age of Enlightenment, then to the Industrial Revolution, the armed forces in the West increasingly began to rely solely on volunteer service to fill ranks. Accordingly, it was then possible to live in European society and never fear being called up for war service since the fighting could be left to the people who had chosen that particular occupation.

While an all-volunteer force seems preferable on paper, there are times when this simply is not possible. In those times, governments introduce conscription to artificially inflate the size of the services to better meet the demand placed on them by conflict. Inevitably, in the modern age, this results in two separate camps forming among conscripts: those who reluctantly head off to fight and those who huddle under the umbrella of the conscientious objector and are instead put to work at home supporting the war effort overseas.

The decision by the British Government to introduce conscription marked the first time in the 20th Century that it had resorted to compelling military service from its able-bodied men, and would be the first of only two occasions in the 20th Century that such a measure would be implemented for war effort. Under the terms of the Military Service Act of 1916, men from 18 to 41 years old were liable to be called up for service in the army unless they were married, widowed with children, serving in the Royal Navy, a minister of religion, or working in one of several "reserved occupations". A second Act in May 1916 extended liability for military service to married men, and a third Act in 1918 extended the upper age limit to 51. Men or employers who objected to an individual's call-up could apply to a local Military Service Tribunal. These bodies could grant an exemption from service, which was usually conditional or temporary. There was right of appeal to a County Appeal Tribunal.

The British act applied only to England, Scotland, and Wales. Canada and New Zealand also eventually implemented conscription but in Australia proposals for compulsory overseas service were twice defeated at the ballot box. While a non-factor at the time, the United States also resorted to conscription in World War I to help shore up its military strength.

|