Whittier is a neighborhood within the Powderhorn community in the U.S. city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, bounded by Franklin Avenue on the north, Interstate 35W on the east, Lake Street on the south, and Lyndale Avenue on the west. It is known for its many diverse restaurants, coffee shops and Asian markets, especially along Nicollet Avenue (also known as "Eat Street"). The neighborhood is home to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and the Children's Theatre Company.

Whittier | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: Eat Street | |

| Motto: The International Neighborhood | |

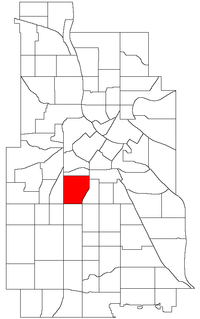

Location of Whittier within the U.S. city of Minneapolis | |

| Coordinates: 44°57′20″N 93°16′40″W / 44.95556°N 93.27778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Hennepin |

| City | Minneapolis |

| Community | Powderhorn |

| Founded | 1849 |

| Established | 1977 |

| Founded by | John Blaisdell |

| Named for | John Greenleaf Whittier |

| City Council Ward | 10 |

| Government | |

| • Council Member | Aisha Chughtai |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.816 sq mi (2.11 km2) |

| Elevation | 866 ft (264 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 14,483 |

| • Density | 18,000/sq mi (6,900/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Postal code | 55404, 55405, 55408 |

| Area code | 612 |

| Website | http://www.whittieralliance.org/ |

While the neighborhood is officially part of the greater Powderhorn community, it is separated from most of those areas by Interstate 35W, and also lies further north than the rest of the community area. Most of Powderhorn is east of Interstate 35W and south of Lake Street; the Whittier neighborhood is west of I-35W and north of Lake Street. Whittier is often associated with adjacent neighborhoods, such as Lowry Hill East in the Calhoun-Isles community to the west and Stevens Square neighborhood in the Central community to the north.

History

editIn the 1800s, Mdewakanton Dakota occupied the area from Saint Anthony Falls toward the Minnesota River following their migration from Mille Lacs Lake and the onward expansion of the quarreling Ojibwa. Temporary Dakota camps were photographed in Whittier which are in the MNHS catalog.

In 1849 at the age of 21, John T. Blaisdell moved from Maine and squatted on land just south of downtown Minneapolis. His brothers eventually came and together they lived in a log house which became Blaisdell School.[3]

Following the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux which expropriated lands to the United States, Blaisdell developed the area south of Downtown Minneapolis into Blaisdell's Addition. For capital, he sold timber to the booming lumber industry and leased land for the Morrison Farm in the east, which the Morrisons eventually purchased.[4]

Blaisdell to Whittier

editAfter the Blaisdell brothers returned from the Civil War in 1865, Minneapolis began growing in population again. Annexations in 1867 and 1883 turned Blaisdell's Addition into South Minneapolis.[5] Entrepreneurs and businessmen soon moved out of Downtown East and built their mansions in the present Washburn-Fair Oaks Mansion District. Much of the Morrison's farm was sold for this expansion. Fair Oaks Park, at the center of this district, was formerly the site of William D. Washburn's mansion. Meanwhile, the southern end of Whittier grew as an agricultural and industrial job center with working-class housing along the Hastings and Dakota tracks of the Milwaukee Road rail line along 29th Street which shipped grain from southern Minnesota. Blaisdell Road became Blaisdell Avenue, extending past the neighborhood to the southern boundaries.

In 1882, Blaisdell built his manor at Nicollet and 24th Street West. The family moved out of Blaisdell School. A year later, Blaisdell, Longfellow and Irving Schools across the southern prairie were annexed to the Minneapolis school system from Hennepin County.[3] In naming tradition with the other schools, the board renamed the school Whittier after the 19th century poet and abolitionist, John Greenleaf Whittier. Like other areas of the city, families would soon call their neighborhoods after the primary school. Called the "millionaire pioneer of the city" by the New York Times, John T. Blaisdell died in 1898.[6]

Into the 20th century, Thomas Lowry and his partners assumed control of the insolvent McCrory's Motor Line. Whittier filled along Lowry's new Nicollet Ave. and 4th Ave. streetcar routes. The increasingly residential nature of southern Minneapolis brought contention with the Milwaukee Road as neighbors petitioned the City Council from 1905 to 1909 to alleviate the effects of the crossings which was blamed for several deaths.[7] The Milwaukee Road offered a failed proposal to elevate the tracks and returned with a $1.3 million plan to depress the tracks and construct a dozen road bridges. After a legal battle with the businesses affected by loss of rail access, the project was upheld and completed in 1916. [8]

Post-War Decline

editThe neighborhood maintained a dense population and high rental occupancy up towards the city's population peak in the 1950s. The latter 20th century followed with other inner core neighborhoods as the postwar boom of the 1960s depleted Whittier's population. The routing of Interstate 35W was modified following city concerns over expensive land acquisition of apartments and mansions including the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.[9] In November 1967, Interstate 35W was built around the neighborhood to spare the Mansion District which was later preserved in its current historic district.

Whittier experienced decline as middle-class residents moved out. The demolition of Nicollet Ball Park in Lyndale neighborhood led to retail failure on the neighborhood's south end. Abandoned buildings and adult bookstores prompted the city to establish the Nicollet/Lake Economic Development District in 1972.[10] Several years passed without activity as Target and Herberger's refused to build. K-Mart finally agreed to become a tenant on the grounds that the City close Nicollet Avenue at Lake Street, and the project was done in 1978.

However a boon for the city, the closing accelerated the neighborhood's problems and Nicollet north of Lake Street was stifled of car traffic. Crime and prostitution became common. Neighbors who stayed had formed a neighborhood association in response to bitter protests over the K-Mart project. The Whittier Alliance (WA) was established in 1977 to monitor the weakened community and rehabilitate housing. WA operated as a Community Development Corporation, developing housing for many years in order to sustain its operations in community outreach. The City attempted to bring about a citizen participation model to assist neighborhoods until with the Legislature's assistance created the Neighborhood Revitalization Program in 1987 to formally address urban issues with funding. The city began designating official neighborhood boundaries at this time and Whittier was formalized.

Millennial rebirth

editSeveral factors had sown seeds for Whittier's comeback from the post-war suburban flight. Nicollet Avenue had not suffered completely. An authentic German restaurant, the Black Forest Inn, opened in 1965 at the corner of 26th and Nicollet, becoming the avenue's main restaurant anchor for decades. As Whittier gained a bohemian culture for its cheap housing, the Artist Quarter jazz club was opened in the 1970s on the adjoining corner establishing a music anchor in the region. During this time, Chinese and Vietnamese businesses began opening on Nicollet following the Vietnam War. The Hip Sing Tong branch headquarters at 2633 Nicollet may explain the presence. Mexican businesses too opened but later in the 1980s on as they became a growing proportion of the immigrant population.

Recognizing the street's potential, the Whittier Alliance and Business Association created a new branding scheme called Eat Street. It was completed in 1997 with a street scape reconstruction along the entire corridor. The abandoned Milwaukee Road trench also gained renewed interest during this time for re-use as a rails to trails transportation corridor.[11] The Midtown Community Works and Midtown Greenway Coalition formed and federal funds were acquired for redevelopment. The first phase of the new Midtown Greenway was built in 1999 and entirely finished in Minneapolis by 2005. In the 2000s, after nearly two decades of private sector disinvestment, three major condominium projects were completed along Nicollet Avenue. In 2011 a major development came to the corner of 26th and Nicollet including a major indoor climbing facility and several new restaurants.[12][13] In 2012, Whittier Alliance and the City of Minneapolis began working to move Kmart and restore Nicollet Avenue including a possible streetcar system.[14] In 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, K-Mart shuttered their doors, closing the last remaining store in the state.[15][16] In 2023, the K-Mart was demolished and as of April 2024, plans are underway for new Nicollet Redevelopment.[17][18]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 12,729 | — | |

| 1990 | 13,051 | 2.5% | |

| 2000 | 15,247 | 16.8% | |

| 2010 | 13,689 | −10.2% | |

| 2020 | 14,483 | 5.8% |

The population of Whittier is 14,483. The neighborhood is 52.8% non-Hispanic White, 23.3% Black, 13.6% Hispanic or Latino, 3.5% Asian, and 6.8% other.[19] The top five single ancestries in 2000 were German (1,780 people), Subsaharan African (1,070 people), Norwegian (870 people), Irish (830 people), and Somali (490 people).

About 82% of households rent.[19] Whittier is the most populous neighborhood in Minneapolis, and second only in density to its neighbor Stevens Square.

Government

editWhittier was part of Ward 6 until redistricting in 2013, which placed Whittier in Ward 10. Ward 10 is currently represented by Minneapolis City Council Member Aisha Chughtai.[20] The neighborhood is currently officially represented by the Whittier Alliance, a community organization founded in 1977, which is recognized by the City of Minneapolis and its Neighborhood Revitalization Program (NRP). These NRP funds allow the Whittier Alliance to work with individuals, families, and businesses to build the community in terms of safety, economic development, and livability. Another informal organization is the Whittier Neighbors, founded in 1996. The Fifth Police Precinct serves the neighborhood under Sector One.

Whittier is in Minnesota Senate District 62, represented by Omar Fateh, and in Minnesota House district 62A, represented by Aisha Gomez.[21] Minneapolis Public Schools Area 23.

Education

editThe Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) is in Whittier.

In the 1990s, the City of Lakes Waldorf School and Watershed High School moved into Whittier. Both schools renovated the American Hardware Mutual Insurance Company building (constructed 1922) at the corner of 24th Street and Nicollet Avenue. Behind this building, at the corner of 24th Street and Blaisdell Avenue, the "play yard" occupies the former site of a Dayton's family mansion. Whittier School had moved to Blaisdell Avenue and closed in the 1960s. [citation needed]

After the departure of Whittier High, the Whittier Alliance led an effort with its NRP capital to build the new Whittier International Elementary School, constructed on the east half of Whittier Park in 2001. This public school serves a population of 350 students in grades K-5.[22]

The Minneapolis Japanese School, a weekend Japanese educational program designated by the Japanese Ministry of Education,[23] previously held its classes at MCAD.[24]

References

edit- ^ "Whittier neighborhood in Minneapolis, Minnesota (MN), 55408, 55405, 55408 detailed profile". City-Data. 2011. Retrieved 2013-11-12.

- ^ "Whittier neighborhood data". Minnesota Compass. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ a b Researched by: Beverly Blaisdell Hochstetter and Margaret Laird / Written by: LynEllen Lacy (1975-06-01). "History of Whittier Elementary School "An Era That is Past"". Whittier Elementary. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ Horace Bushnell Hudson (1908). A Half Century of Minneapolis. Hudson Pub. Co. Original from the University of Virginia. p. 36.

John T. Blaisdell.

- ^ "A History of Minneapolis: Governance and Infrastructure". Minneapolis Library. 2001. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ "DUPED BY HIS ATTORNEY; J. F. COLLOM FORGES THE NAME OF A CLIENT. JOHN T. BLAISDELL AMAZED TO FIND $227,000 OF HIS PAPER AFLOAT-- THE LAWYER ADMITS HIS GUILT". New York Times. August 8, 1889. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "The Evolution of the Midtown Greenway" (PDF). Midtown Community Works. May 2001. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ Eden Spencer (1905–1914). "From Neighborhood Activism to City Power". Minneapolis Journal.

- ^ Liddy J. Howard (May 1997). "Stevens Square-Loring Heights "A Community Defined"". Center for Urban and Regional Affairs University of Minnesota.

- ^ "Urban Renewal at Lake and Nicollet". Midtown Community Works. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- ^ Kari Linder (June 8, 1999). "Neighborhoods consider green space goals for Midtown Greenway". SW Journal. Archived from the original on December 30, 2004. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Scaling New Heights". Southwest Journal.

- ^ "A New Hangout on Nicollet". Southwest Journal.

- ^ "Minneapolis looks to move Kmart, restore Nicollet Avenue". Star Tribune.

- ^ Lisicky, Michael. "Kmart Continues To Serve And Divide A South Minneapolis Community". Forbes. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ "Why Kmart still stands at Lake and Nicollet as other Minnesota outlets close down". MPR News. 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ "K-Mart Development and Nicollet Reopening". Whittier Alliance. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ "Watch former Minneapolis Kmart building demolition". MPR News. 2023-11-17. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ a b "Whittier". Minnesota Compass. Retrieved 2024-05-31.

- ^ "Find My Ward". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Rep. Aisha Gomez". Minnesota House of Representatives. Minnesota Legislature. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Whittier International". US News and World Report. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "日本人学校及び日本語補習授業校のご案内" (Archive). Consulate General of Japan in Chicago. Retrieved on April 8, 2015.

- ^ "English Page" (Archive). Minneapolis Japanese School. October 6, 2001. Retrieved on April 8, 2015.

Further reading

edit- Nicollet urban plans

- Minneapolis City Coordinator's Office 1972 Nicollet Lake Development District Plan. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis City Coordinator's Office.

- Barton-Aschman Associates 1994 Nicollet Avenue Corridor Study. Minneapolis, MN: Barton-Aschman Associates.

- CPED, Nicollet Avenue Task Force 2000 Nicollet Avenue: The Revitalization of Minneapolis’ Main Street. Minneapolis.

- BKV Group 2001 Nicollet Avenue: … vision for the present and future. 2001 Development Plan. 10/15/01.

- Corridor Revitalization, Minneapolis Case Studies 2005?

- Whittier urban plans

- Holt, Wexler, Farnam 1995 Whittier Alliance Organizational Assessment. 3/17/95.

- Minneapolis City Planning Commission. 1960. Comprehensive Planning for the Whittier Neighborhood. Minneapolis, MN: City of Minneapolis Planning Commission.

- Minneapolis Department of Planning and Development 1976 Whittier East Design Study. Minneapolis.

- Team 70 Architects 1977 Whittier urban design framework. Minneapolis.

- Whittier Alliance 1978 Whittier Urban Design Framework: program implementation guide. Minneapolis.

- McNamara, John 1979 Whittier Alliance Program Activities Year 2 Action Plan. Minneapolis.

- McNamera, John, Ranae Hanson, and Dayton-Hudson Foundation 1981 Partners. Minneapolis: Dayton-Hudson.

- Minneapolis Planning Department, NRP 1991 Whittier: planning information base. Minneapolis MN: Office of city coordinator.

- Whittier Alliance 1992 Whittier Neighborhood Phase I Action Plan. Minneapolis, MN: Neighborhood Revitalization Program.

- Whittier Alliance, and Change Architects. 2001. A Decade of Change: The Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program & The Whittier Neighborhood. Minneapolis, MN: Whittier Alliance & Change Architects.

- Whittier Alliance 2002 Whittier Neighborhood NRP Phase II Action Plan.

- Whittier Alliance 2005 Whittier Neighborhood NRP Phase II Neighborhood Action Plan.

- Heritage Preservation Commission (Gail Bronner) 1976 Washburn-Fair Oaks: A study for preservation.

- Research articles

- Allen, Jeffrey 2003 Affordable Housing in the Whittier Neighborhood. Minneapolis: Whittier Alliance.

- Arwade, Jennifer 2000 Citizen Participation in City Planning: how much is enough? The Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program and Trenton, New Jersey. A senior thesis submitted to the Department of Politics for B.A. Princeton NJ: Princeton University. (Whittier case study is p. 42-46).

- Dowdell, Richard, Amy Jeu, and Marcus Martin 2001 Whittier Analysis of Impacts on Residential Property Values. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs

- Fagotto, Elena and Archon Fung 2005 The Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program: an experiment in empowered participatory government

- Fagotto, Elena and Archon Fung 2005 Appendix to The Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program

- Fagotto, Elena and Archon Fung 2006 Empowered Participation in Minneapolis: The Neighborhood Revitalization Program. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 30, No. 3: 638-55

- Goetz, Edward and Mara Sidney 1994 Neighborhood Revitalization for Whom? CURA Reporter, June 94:11-15. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Goetz, Edward and Mara Sidney 1994 Impact of the Minneapolis Neighborhood Revitalization Program on Neighborhood Organizations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Goetz, Edward and Mara Sidney 1994 Revenge of the property owners: community development and the politics of property. Journal of Urban Affairs 16(4):319-334.

- Goetz, Edward, Hin Kin Lam, and Anne Heitlinger 1996 There Goes the Neighborhood? Subsidized Housing in Urban Neighborhoods. CURA Reporter April 96:1-6. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Goetz, Edward, Hin Kin Lam, and Anne Heitlinger 1996 There Goes the Neighborhood? The Impact of Subsidized Multi-Family Housing on Urban Neighborhoods. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Goetz, Edward and Brian Schaffer 2004 An Evaluation of the Minneapolis Neighborhood Information System. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- HACER 1998 Latino Realities: A Vibrant Community Emerges in South Minneapolis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs

- Institute on Race and Poverty 1998 Neighborhood Atlas for the building better futures initiative: Whitter. 7/17/98. Minneapolis: Institute on Race and Poverty.

- Jacobson, Justin 2005 Eat Street. Geography Department Master’s Thesis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Malaby, Elizabeth and Tom Brady-Leighton 1994 Whittier Homeownership Center Targeting Project. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs. (the focus group discussions provided insights into Whittier Alliance efforts to attract new homeowners and retain current ones)

- Matson, Jeffrey Minneapolis Neighborhood Information System 2002 Whittier Supportive Housing Project. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs. (simple maps and stats for supportive Housing in the Lydia area

- Mielke, Andrew (for the Whittier Housing Corporation) 1998 Housing in the Whittier Neighborhood. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Pike, Ronald 1989 Multi-Family Housing change in the Whittier Neighborhood: responses to a 1960s building boom of 2 ½ story walkups. Department of Geography, University of Minnesota.

- Rohe, W Learning from Adversity, Whittier housing corp

- Sage-Martinson, Jonathon 1998 Whittier Works Business Survey. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs

- Ramirez, Shannon and David Scheie 1991 Cops and Neighbors: An evaluation of the Whittier Community Based Policing Project. St. Paul MN: Rainbow Research.

- Smith, Rebecca Lou 1980 Whittier: A Revitalization Effort in the Inner City. CURA Reporter 10(3):10-12. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Smith, Rebecca Lou 1982 Neighborhood Inside and Out: Comparative Perspectives on the Meaning of "Neighborhood." Dissertation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Smith, Rebecca Lou and Thomas Anding 1980 Community Involvement in the Whittier Neighborhood: An Analysis of Neighborhood Conditions and Neighborhood Change. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- History

- Adams, John S., and Barbara VanDrasek 1993 Minneapolis-St. Paul: People, place and public life. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. (historical for Nicollet)

- Dipman, David, and Hila Dipman 1974 Whittier's Early Beginnings. Notes for the Whittier Day Celebration, September 8, 1974. Minneapolis, MN.

- Hart, Joseph 1997 How Little Asia Was Born. City Pages, Minneapolis/St. Paul. March 12.

- Martin, Judith 1983 Minneapolis Survey: How the City Grew and What Should be Preserved. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs.

- Olson, Russell L. 1976. The Electric Railways of Minnesota. Hopkins, MN: Minnesota Transportation Museum. (includes Nicollet Ave line)

- Thornley, Stew. 1988. On To Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Millers. Minneapolis, MN: Nodin Press. (includes history of the old Nicollet line out to the ballpark)

- Whittier Alliance (John Share, Carol Anderson, Sally Grans, Lisa Kugler) 1985 History of 2-1/2 Story Walk-up Apartments in Whittier. Minneapolis, MN: Whittier Alliance.

- News articles

- Hammond, Ruth 1977 There's an effort underway to improve Whittier neighborhood's poor self-image. Minneapolis Tribune. December 10.

- Hammond, Ruth 1982 When Dayton's became a pal to Whittier, the whole neighborhood brightened up. Minneapolis Tribune. April 3.

- Inskip, Leonard 1982 Whittier: a model partnership for improvement. Minneapolis Tribune. March 9.

- Inskip, Leonard 1984 Grant leaves Whittier neighbors a stronger, more effective group. Minneapolis Star and Tribune. April 25.

- Leydon, Peter 1992 Homeowners Take Over Board. Star Tribune 11/5/92. Minneapolis.

- Leydon, Peter 1992 Whittier’s Vision, city agenda in conflict. Star Tribune 2/25/92. Minneapolis.

- Buchta, Jim 1993 Spotlight on Whittier. Star Tribune Home Section 11/2/93.

- Iggers, Jeremy 1997 Eat Street. Minneapolis Star-Tribune. January 3.

- Jossi, Frank 2002 Neighbors plan Nicollet's facelift. The Business Journal, Minneapolis - St. Paul. May 17.

- Smith, Scott D. 2002 'Eat Street' plans more retail. The Business Journal, Minneapolis - St. Paul. May 15.