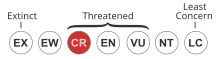

The whitefin swellshark (Cephaloscyllium albipinnum) is a species of catshark, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae, endemic to southeastern Australia. It is found 126–554 m (413–1,818 ft) down, on the outer continental shelf and upper continental slope. Reaching 1.1 m (3.6 ft) in length, this shark has a very thick body and a short, broad, flattened head with a large mouth. It is characterized by a dorsal color pattern of dark saddles and blotches over a brown to gray background, and light fin margins. When threatened the whitefin swellshark can inflate itself with water or air to increase its size.[2] Reproduction is oviparous. As of 2019 The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Critically Endangered due to the significant decline of the population.

| Whitefin swellshark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Scyliorhinidae |

| Genus: | Cephaloscyllium |

| Species: | C. albipinnum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cephaloscyllium albipinnum | |

Taxonomy

editEarly specimens of the whitefin swellshark were often mistaken for the Australian swellshark (C. laticeps) or the draughtsboard shark (C. isabellum). In 1994, it was identified as a new species and known provisionally as Cephaloscyllium "sp. A", until it was formally described by Peter Last, Hiroyuki Motomura, and William White, in a 2008 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) publication.[3] Its specific epithet albipinnum comes from the Latin albi meaning "white", and pinna meaning "fin", referring to its distinctive white fin margins. The type specimen is a 1.0 m (3.3 ft) long adult male caught near Maria Island, Tasmania.[3]

Description

editThe whitefin swellshark is a stocky species measuring up to 1.1 m (3.6 ft) long.[4] The head is short, very wide, and greatly flattened, with a broadly rounded snout. The slit-like eyes are positioned high on the head, and are followed by tiny spiracles. The nostrils are preceded by laterally expanded flaps of skin that do not reach the mouth. The mouth is large and strongly arched, without furrows at the corners. There are 90–116 upper tooth rows and 97–110 lower tooth rows; each tooth has three central cusps and often 1–2 additional small, lateral cusplets. The upper teeth are exposed when the mouth is closed. The fourth and fifth pairs of gill slits lie over the pectoral fin bases and are shorter than the first three.[3]

The pectoral fins are large and broad, with gently concave posterior margins. The first dorsal fin is rounded and originates over the forward half of the pelvic fin bases. The second dorsal fin is much smaller and somewhat triangular, originating over the anal fin. The pelvic fins are small; males have very long claspers. The anal fin is larger than the second dorsal fin and is rounded in juveniles, becoming more angular in adults. The large caudal fin has a distinct lower lobe and a deep ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe. The skin is thick and made rough by widely spaced, arrowhead-shaped dermal denticles with three horizontal ridges. The dorsal coloration is brown to gray with 9–10 dark saddles closely alternating with lateral blotches, including a large round blotch encompassing the gill slits; the fins are dark above with variably pale margins. The underside is lighter than the back, sometimes with darker or lighter blotches. Juveniles have more regular and better-defined blotches than adults.[3][4]

Distribution and habitat

editThe whitefin swellshark is found off southeastern Australia from Batemans Bay, New South Wales to the Great Australian Bight as far as Eucla, Western Australia, including southern Tasmania from Maria Island to Point Hibbs. It is a bottom-dweller that inhabits the outer continental shelf and upper continental slope, at a depth of 126–554 m (413–1,818 ft).[3]

Biology and ecology

editLike other members of its genus, the whitefin swellshark can swallow water or air to dramatically increase its girth, as a defense against predators.[4] It is oviparous; the eggs are enclosed in smooth, light yellow flask-shaped capsules 9.8–11.6 cm (3.9–4.6 in) long and 5 cm (2.0 in) wide, with flanged edges and short horns at the corners that support long, coiled tendrils. The smallest known mature males and females measure 70 cm (28 in) and 98 cm (39 in) long respectively.[3][4]

Human interactions

editThe whitefin swellshark resides in a heavily fished region and while not a commercially targeted fish, are commonly captured as bycatch in trawls.[2] The Australian South East Trawl Fishery, which operates off New South Wales, over a third of this shark's range reported that its catch rate dropped over 30% between 1967–77 and 1996–97. The South East Trawl Fishery Observer Program off southern Australia has also reported a slight population decline. As a result, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the whitefin swellshark as critically endangered, and recommended close monitoring of bycatch levels.[1] It is one of four species identified as threatened with extinction by trawling in a 2021 report.[5]

References

edit- ^ a b Pardo, S.A.; Dulvy, N.K.; Barratt, P.J.; Kyne, P.M. (2019). "Cephaloscyllium albipinnum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T42706A68615830. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T42706A68615830.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b White, Wil; Bray, Dianne. "Whitefin Swellshark, Cephaloscyllium albipinnum". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Last, P.R., H. Motomura, and W. T. White (2008). "Cephaloscyllium albipinnum sp. nov., a new swellshark (Carcharhiniformes: Scyliorhinidae) from southeastern Australia" in Last, P.R., W.T. White and J.J. Pogonoski (eds). Descriptions of new Australian Chondrichthyans. CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research Paper No. 022: 147–157. ISBN 0-1921424-1-0 (corrected) ISBN 1-921424-18-2 (invalid, listed in publication).

- ^ a b c d Last, P.R. and J.D. Stevens (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed). Harvard University Press. p. 209. ISBN 0-674-03411-2.

- ^ Readfearn, Graham (15 March 2021). "Threatened Australian shark and skates at 'extreme risk' of being wiped out". Guardian Online. Retrieved 17 March 2021.