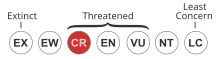

The western chimpanzee or West African chimpanzee[1] (Pan troglodytes verus) is a Critically Endangered subspecies of the common chimpanzee. It inhabits western Africa, specifically Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Senegal, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, but has been extirpated in three countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, and Togo.[1]

| Western chimpanzee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Pan |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | P. t. verus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Pan troglodytes verus Schwarz, 1934

| |

| |

Etymology

editThe taxonomical genus Pan is derived from the Greek god of fields, groves, and wooded glens, Pan. The species name troglodytes is Greek for 'cave-dweller', and was coined by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his Handbuch der Naturgeschichte (Handbook of Natural History) published in 1779. Verus is Latin for 'true', and was given to this subspecies in 1934 by Ernst Schwarz, who originally named it as Pan satyrus verus.[2]

Taxonomy and genetics

editThe western chimpanzee (P. t. verus) is a subspecies of the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), along with the central chimpanzee (P. t. troglodytes), the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (P. t. ellioti), and the eastern chimpanzee (P. t. schweinfurthii).[3] The western chimpanzee last shared a common ancestor with P. t. ellioti between 0.4 and 0.6 million years ago (mya) and with P. t. troglodytes and P. t. schweinfurthii 0.38–0.55 mya.[4]

Western chimpanzees are the most genetically differentiated and homozygous subspecies of the common chimpanzee.[5]

Distribution and habitat

editThe population of the western chimpanzee once spanned from southern Senegal all the way east to the Niger River.[1][6] Today, the largest populations remaining are found in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.[1][7]

Behavior

editDiet and hunting

editMale and female western chimpanzees differ in their prey. In Fongoli, Senegal, Senegal bushbabies account for 75% of females' prey and 47% of the males'. While males will prey more on monkeys, such as green monkeys (27%) and Guinea baboons (18%), only males were observed to hunt patas monkeys and only females were observed to hunt banded mongooses. Both will occasionally hunt bushbucks, preferring fawns, when given the chance. Adult, adolescent, and juvenile females are slightly more likely to hunt with tools than males of the same age group.[8] Chimpanzees near Kédougou, Senegal have been observed to create spears by breaking straight limbs off trees, stripping them of their bark and side branches, and sharpening one end with their teeth. They then used the weapons to hunt galagos sleeping in hollows.[9]

Unique behaviors

editWestern chimpanzees have unique behaviors never observed in any of the other subspecies of the chimpanzee. In fact, their behaviour is so diverged from that of their fellow subspecies of chimpanzee that it has been proposed West African chimpanzees may be a distinct species in their own right.[10] They make wooden spears to hunt other primates, use caves as homes, share plant foods with each other, and travel and forage during the night. They also submerge themselves in water and play in it to stay cool in the oppressive heat.[10][11][12]

Female west African chimpanzees are quite gregarious and often support one another in conflicts with males, resulting in a more gender-balanced hierarchy than that of the rigidly patriarchal east african chimpanzees.[citation needed] Female West African chimpanzees have been observed hunting and accompany males on territorial patrols, playing a more important role in social dynamics than other chimpanzee subspecies.[13] While it was traditionally accepted that only female chimpanzees immigrate and males remain in their natal troop for life, western chimpanzees uniquely exhibit female and male immigration between groups, suggesting males are less territorial and more willing to accept unfamiliar males.[14] Paternity tests indicate males frequently mate with females from several different communities, siring infants from them. There are even cases of solitary male western chimpanzees, while in any other population, a chimpanzee couldn't survive alone.[15] Male West African chimpanzees generally are respectful of females and do not forcibly confiscate food from them,[16] which may at least partly stem from the gregarious females forming alliances.[17] Among the Tai forest community, infants are often adopted by unrelated adults, with both sexes adopting infants in equal measure.[18] Female western chimpanzees also can rebuff the unwanted advances of males and select males to breed with on their own terms. This further is in line with the active and possibly co-dominant role female western chimpanzees play in their communities.[19]

Conservation status

editThe IUCN lists the western chimpanzee as Critically Endangered on the Red List of Threatened Species.[1] There are an estimated 21,300 to 55,600 individuals in the wild.[1] The primary threat to the western chimpanzee is habitat loss, although it is also killed for bushmeat.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Humle, T.; Boesch, C.; Campbell, G.; Junker, J.; Koops, K.; Kuehl, H.; Sop, T. (2016) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Pan troglodytes ssp. verus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T15935A102327574. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T15935A17989872.en. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Meder, A. (1995). "Men who named the African apes". Gorilla Journal (11). Germany.

- ^ Hof, J.; Sommer, V. (2010). Apes Like Us: Portraits of a Kinship. Mannheim: Edition Panorama. p. 114. ISBN 978-3-89823-435-1.

- ^ Gonder, M. K.; Locatelli, S.; Ghobrial, L.; Mitchell, M. W.; Kujawski, J. T.; Lankester, F. J.; Stewart, C.-B.; Tishkoff, S. A. (2011). "Evidence from Cameroon reveals differences in the genetic structure and histories of chimpanzee populations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (12): 4766–4771. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015422108. PMC 3064329. PMID 21368170.

- ^ de Manuel, M.; Kuhlwilm, M.; Frandsen, P.; et al. (2016). "Supplementary materials for chimpanzee genomic diversity reveals ancient admixture with bonobos". Science. 354 (6311): 1–129. doi:10.1126/science.aag2602. PMC 5546212. PMID 27789843.

- ^ "Western chimpanzee - population & distribution". Panda.org. World Wide Fund for Nature. 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "Regional action plan for the conservation of western chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) 2020–2030" (PDF). westernchimp.org/the-plan-overview. IUCN. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Pruetz, J. D.; Bertolani, P.; Ontl, K. B.; Lindshield, S.; Shelley, M.; Wessling, E. G. (15 April 2015). "New evidence on the tool-assisted hunting exhibited by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in a savannah habitat at Fongoli, Sénégal". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (4). Royal Society Publishing: 140507. Bibcode:2015RSOS....240507P. doi:10.1098/rsos.140507. PMC 4448863. PMID 26064638.

- ^ Pruetz, Jill D.; Bertolani, Paco (2007). "Savanna Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, Hunt with Tools". Current Biology. 17 (5): 412–417. Bibcode:2007CBio...17..412P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.042. PMID 17320393. S2CID 16551874.

- ^ a b Last, C. "Are western chimpanzees a new species of Pan?". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Almost human". National Geographic. 15 May 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Fongoli chimps spearing. National Geographic.

- ^ Lemoine, S.; Boesch, C.; Preis, A.; Samuni, L.; Crockford, C.; Wittig, R. M. (2020). "Group dominance increases territory size and reduces neighbour pressure in wild chimpanzees". Royal Society Open Science. 7 (5): 200577. Bibcode:2020RSOS....700577L. doi:10.1098/rsos.200577. PMC 7277268. PMID 32537232.

- ^ Sugiyama, Y.; Koman, J. (1979). "Social structure and dynamics of wild chimpanzees at Bossou, Guinea". Primates. 20 (3): 323–339. doi:10.1007/BF02373387. S2CID 9267686.

- ^ Sugiyama, Y. (1999). "Socioecological factors of male chimpanzee migration at Bossou, Guinea". Primates. 40 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1007/BF02557702. PMID 23179532. S2CID 24529322.

- ^ Larson, S. "Female chimps more likely than males to hunt with tools". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ^ van Leeuwen, K. L. (28 October 2013). Bisexual bonding in West African chimpanzees: implications for the evolution of human sociality (Thesis). hdl:1874/285302.

- ^ Moskowitz, C. (26 January 2010). "Altruistic chimpanzees adopt orphans". livescience.com. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Stumpf, R. M.; Boesch, C. (October 2006). "The efficacy of female choice in chimpanzees of the Taï Forest, Côte d'Ivoire". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 60 (6): 749–765. doi:10.1007/s00265-006-0219-8. S2CID 986042.