The water-energy nexus is the relationship between the water used for energy production,[1] including both electricity and sources of fuel such as oil and natural gas, and the energy consumed to extract, purify, deliver, heat/cool, treat and dispose of water (and wastewater) sometimes referred to as the energy intensity (EI). Energy is needed in every stage of the water cycle from producing, moving, treating and heating water to collecting and treating wastewater.[2] The relationship is not truly a closed loop as the water used for energy production need not be the same water that is processed using that energy, but all forms of energy production require some input of water making the relationship inextricable.

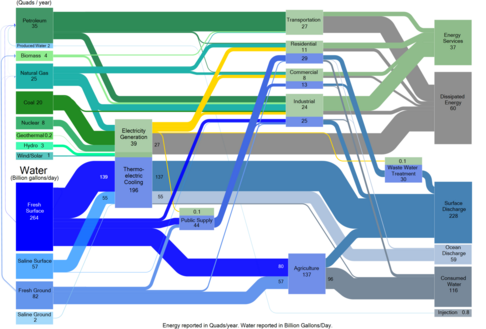

Among the first studies to evaluate the water and energy relationship was a life-cycle analysis conducted by Peter Gleick in 1994 that highlighted the interdependence and initiated the joint study of water and energy.[3] In 2014 the US Department of Energy (DOE) released their report on the water-energy nexus citing the need for joint water-energy policies and better understanding of the nexus and its susceptibility to climate change as a matter of national security.[4] The hybrid Sankey diagram in the DOE's 2014 water-energy nexus report summarizes water and energy flows in the US by sector, demonstrating interdependence as well as singling out thermoelectric power as the single largest user of water, used mainly for cooling.

Water used in the energy sector

editAll types of power generation consume water either to process the raw materials used in the facility, constructing and maintaining the plant, or to just generate the electricity itself. Renewable power sources such as photovoltaic solar and wind power, which require little water to produce energy, require water in processing the raw materials to build. Water can either be used or consumed, and can be categorized as fresh, ground, surface, blue, grey or green among others.[1] Water is considered used if it does not reduce the supply of water to downstream users, i.e. water that is taken and returned to the same source (instream use), such as in thermoelectric plants that use water for cooling and are by far the largest users of water.[4] While used water is returned to the system for downstream uses, it has usually been degraded in some way, mainly due to thermal or chemical pollution, and the natural flow has been altered which does not factor into an assessment if only the quantity of water is considered. Water is consumed when it is removed completely from the system, such as by evaporation or consumption by crops or humans. When assessing water use all these factors must be considered as well as spatiotemporal considerations making precise determination of water use very difficult. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), water stress also poses risks to the transport of fuels and materials. In 2022, droughts and severe heatwaves led to low water levels in key European rivers such as the Rhine, limiting barge transport of coal, chemicals and other materials.[5]

Spang et al. (2014) conducted a study looking at the water consumption for electricity production (WCEP) internationally that both showed the variation in energy types produced across countries as well as the vast differences in efficiency of power production per unit of water use (Figure 1).[1] Operations of water distribution systems and power distribution systems under emergency conditions of limited power and water availability is an important consideration for improving the overall resilience of the water – energy nexus. Khatavkar and Mays (2017a) present a methodology for control of water distribution and power distribution systems under emergency conditions of drought and limited power availability to ascertain at least minimal supply of cooling water to the power plants.[6] Khatavkar and Mays (2017) applied an optimization model for water – energy nexus system for a hypothetical regional level system which showed an improved resilience for several contingency scenarios.[7]

Increasingly controversial has been the use of water resources for hydraulic fracturing of shale gas and tight oil reserves. Many environmentalists are deeply concerned about the potential for such operations to exacerbate local water scarcity (since the water volumes required are large) and to produce considerable volumes of polluted water (both directly through pollution of fracking water, and indirectly through contamination of groundwater).[8] With rising energy prices in North America and Europe in the 2020s it is likely that government and industry interest in hydraulic fracturing will grow.

Energy intensity

editThe operation of urban water systems requires substantial energy support. Key processes such as water transfer,[9] consumption,[10] and wastewater treatment[11] consume significant amounts of energy, sparking discussions about the energy intensity and carbon emissions of water systems.

US (California)

editIn 2001, operating water systems in the US consumed approximately 3% of the total annual electricity (~75 TWh).[12] The California's State Water Project (SWP) and Central Valley Project (CVP) are together the largest water system in the world with the highest water lift, over 2000 ft. across the Tehachapi Mountains, delivering water from the wetter and relatively rural north of the state, to the agriculturally intensive central valley, and finally to the arid and heavily populated south. Consequently, the SWP and CVP are the single largest consumers of electricity in California consuming approximately 5 TWh of electricity each per year.[12] In 2001, 19% of the state's total electricity use (~48 TWh/year) was used in processing water, including end uses, with the urban sector accounting for 65% of this.[13] In addition to electricity, 30% of California's natural gas consumption was due to water-related processes, mainly residential water heating, and 88 million gallons of diesel was consumed by groundwater pumps for agriculture.[13] The residential sector alone accounted for 48% of the total combined electricity and natural gas consumed for water-related processes in the state.[12][13]

According to the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) Energy Division's Embedded Energy in Water Studies report:

"'Energy Intensity' refers to the average amount of energy needed to transport or treat water or wastewater on a per unit basis."[14]

Energy intensity is sometimes used synonymous with embedded or embodied energy. In 2005, water deliveries to Southern California were assessed to have an average EI of 12.7 MWh/MG, nearly two-thirds of which was due to transportation.[13] Following the findings that a fifth of California's electricity is consumed in water-related processes including end-use,[13] the CPUC responded by authorising a statewide study into the relationship between energy and water that was conducted by the California Institute for Energy and Environment (CIEE), and developed programs to save energy through water conservation.[14][15]

Arab region

editAccording to the World Energy Outlook 2016, in the Middle East, the water sector's share of total electricity consumption is expected to increase from 9% in 2015 to 16% by 2040, because of a rise in desalination capacity. The Arab region which includes the following countries: Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauretania, Morocco, Oman, Palestinian Territories, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Qatar, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Some general characteristics of the Arab region is that it is one of the most water stressed regions of the world, rain fall is mostly rare, or it rains in an unpredictable

pattern.[16] The cumulative area of the Arab region is approximately 10.2% of the world's area, but the region only receives 2.1% of the world's average annual precipitation. Further, the region accommodates 0.3% of the world's annual renewable water resources (ACSAD 1997). Consequently, the region has experienced a declining fresh water supply per capita, roughly a shortage of 42 cubic kilometers of water demand.[17] This shortage is expected to grow three times by 2030, and four times by 2050.[18] This is crucially alarming given the world's economic stability highly depends on the Arab region.[18]

There are numerous methods to mitigate the growing gap of fresh water supply per capita. One applicable method is desalination which is ubiquitous particularly in the GCC region.[18] All of the world's desalination capacity, approximately 50% is contained in the Arab region, and almost all of that 50% is held in the GCC countries.[18] Countries such as Bahrain provides 79% of its fresh water through desalination, Qatar is around 75%, Kuwait around 70%, Saudi Arabia 15%, and the UAE about 67%. These Persian Gulf countries built enormous desalination plants to fulfill the water supply shortages as these countries have developed economically.[18][19] Agriculture in the GCC region accounts for approximately 2% of its GDP however, it utilizes 80% of water produced.[19] It should also be noted that it requires immense amount of energy mostly from oil to operate these desalination plants. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Kuwait will face difficulty to meet the demand for desalination if the current trend continues. The GCC spends 10–25% of its generated electric power to desalinate water.[20][21][22]

Hydroelectricity

editHydroelectricity is a special case of water used for energy production mainly because hydroelectric power generation is regarded as being cleaner and renewable energy, and dams (the main source of hydroelectric production) serve multiple purposes besides energy generation, including flood prevention, storage, control and recreation which make justifiable allocation analyses difficult.[1] Furthermore, the impacts of hydroelectric power generation can be hard to quantify both in terms of evaporative consumptive losses and altered quality of water, since damming results in flows that are much colder than for flowing streams. In some cases the moderation of flows can be seen as a rivalry of water use in time may also need to accounted for in impact analysis. Willingness to pay can be used as an estimate to determine the value of the cost.

Retrofitting existing dams to produce electricity has been one approach to hydroelectricity. While using dams to produce electricity is seen as a cleaner form of energy, it does not come without its own challenges to the environment. Hydorelectric power has typically been seen as a lower carbon emission strategy to generating power; however, recent studies have been linked dams to greenhouse gas emissions.[23] Galy-Lacaux et al conducted a study to measure the emissions produced by the Petit Saut Dam on the Sinnamary River in French Guyana for a two year period. The researchers found that About 10% of the carbon stored in soil and vegetation was released in gaseous form within 2 years.[23]

Water Availability

editBecause of the shift in developing new renewable energy technologies, there is a new added stress to water availability. Renewable energy methods, such as biofuels, concentrating solar power (CSP), carbon capture, utilization and storage or nuclear power, are quite water intensive.[24] Water scarcity has a huge impact on energy production and reliability.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Spang, E. S., Moomaw, W. R., Gallagher, K. S., Kirshen, P. H., and Marks, D. H. (2014). "The water consumption of energy production: an international comparison." Environmental Research Letters, 9(10), 105002.

- ^ "Water-Energy Nexus • Center for Water-Energy Efficiency". Center for Water-Energy Efficiency. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- ^ Gleick, P. H. (1994). "Water and Energy." Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, 19(1), 267–299.

- ^ a b Bauer, D., Philbrick, M., and Vallario, B. (2014). "The Water-Energy Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities." U.S. Department of Energy.

- ^ IEA (2023), Clean energy can help to ease the water crisis, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/commentaries/clean-energy-can-help-to-ease-the-water-crisis, License: CC BY 4.0

- ^ Khatavkar, P., & Mays, L. W. (2017 a) Model for the Real-Time Operation of Water Distribution Systems under Limited Power Availability. In World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2017 (pp. 171–183).

- ^ Khatavkar, P., & Mays, L. W. (2017). Testing an Optimization/Simulation Model for the Real-Time Operations of Water Distribution Systems under Limited Power Availability. In Congress on Technical Advancement 2017 (pp. 1–9).

- ^ Buono, Regina; Lopez-Gunn, Elena; Mackay, Jennifer; Staddon, Chad (2020). Regulating Water Security in Unconventional Oil and Gas (1st 2020 ed.). Cham. ISBN 978-3-030-18342-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Liu, Yueyi; Zheng, Hang; Wan, Wenhua; Zhao, Jianshi (2023). "Optimal operation toward energy efficiency of the long-distance water transfer project". Journal of Hydrology. 618: 129152.

- ^ Li, Zonghan; Wang, Chunyan; Liu, Yi (2024). "Enhancing the explanation of household water consumption through the water-energy nexus concept". npj Clean Water. 7 (8).

- ^ Chen, Shaoqing; Zhang, Linmei; Liu, Beibei; Yi, Hang; Su, Hanshi; Kharrazi, Ali; Jiang, Feng; Lu, Zhongming; Crittenden, John C.; Chen, Bin (2023). "Decoupling wastewater-related greenhouse gas emissions and water stress alleviation across 300 cities in China is challenging yet plausible by 2030". Nature Water. 1: 534–546.

- ^ a b c Cohen, R., Nelson, B., and Wolff, G. (2004). "Energy Down The Drain: The Hidden Costs of California's Water Supply." E. Cousins, ed., Natural Resources Defense Council

- ^ a b c d e Klein, G., Krebs, M., Hall, V., O'Brien, T., and Blevins, B. B. (2005). "California's Water – Energy Relationship." California Energy Commission, Sacramento, California.

- ^ a b Bennett, B., and Park, L. (2010). "Embedded Energy in Water Studies Study 1: Statewide and Regional Water-Energy Relationship." California Public Utilities Commission Energy Division.

- ^ Bennett, B., and Park, L. (2010). "Embedded Energy in Water Studies Study 2: Water Agency and Function Component Study and Embedded Energy- Water Load Profiles." California Public Utilities Commission Energy Division.

- ^ UNDP (2013) Water governance in the Arab Region: managing scarcity and securing the future. UNDP, New York.

- ^ Devlin J (2014) Is water scarcity dampening growth prospects in the Middle East and North Africa? Brookings Institution, 24 June 2014

- ^ a b c d e World Bank (2012) Renewable energy desalination: an emerging solution to close the water gap in the Middle East and North Africa. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- ^ a b Booz and Company (2014) Achieving a sustainable water sector in the GCC: managing supply and demand, building institutions, 8 May 2014.

- ^ Fath H, Sadik A, Mezher T (2013) Present and future trend in the production and energy consumption of desalinated water in GCC countries. Int J Therm Env Eng 5(2):155–162

- ^ Amer, Kamel, et al., editors. The Water, Energy, and Food Security Nexus in the Arab Region. 1st ed., ser. 2367–4008, Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- ^ Badran, Adnan, et al., editors. Water, Energy, & Food Sustainability in the Middle East. 1st ed., ser. 978-3-319-48920-9, Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- ^ a b Galy-Lacaux, Corinne; Delmas, Robert; Jambert, Corinne; Dumestre, Jean-François; Labroue, Louis; Richard, Sandrine; Gosse, Philippe (December 1997). "Gaseous emissions and oxygen consumption in hydroelectric dams: A case study in French Guyana". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 11 (4): 471–483. Bibcode:1997GBioC..11..471G. doi:10.1029/97GB01625.

- ^ "Introduction to the water-energy nexus – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

External links

edit- California's Water – Energy Relationship

- WaterEnergyNEXUS – Advanced Technologies and Best Practices

- Embedded Energy in Water Studies Study 1: Statewide and Regional Water-Energy Relationship

- Embedded Energy in Water Studies Study 2: Water Agency and Function Component Study and Embedded Energy- Water Load Profiles

- The Water-Energy Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities

- [1]

- Thirsty Energy