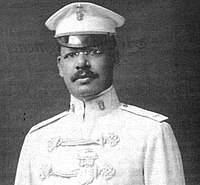

Walter Howard Loving (December 17, 1872 – February/March 1945) was an African American soldier and musician most noted for his leadership of the Philippine Constabulary Band. The son of a former slave, Loving led the band during the 1909 U.S. presidential inaugural parade, where it formed the official musical escort to the President of the United States, the first time a band other than the U.S. Marine Band had been assigned that duty.

Walter Loving | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Walter Howard Loving |

| Born | December 17, 1872 Nelson County, Virginia, United States |

| Died | February–March 1945 (aged 72) Manila, Philippines |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | United States Army Volunteer Army of the United States Philippine Constabulary Philippine Commonwealth Army |

| Rank | Major (Philippine Constabulary) Major (U.S. Army) Lieutenant Colonel (Philippine Commonwealth Army) |

| Unit | Philippine Constabulary Band Philippine Army Orchestra U.S. Army Military Intelligence Division |

| Awards | Presidential Merit Award Distinguished Conduct Star Philippine Campaign Medal |

Loving is believed to have been the first African American to conduct a musical performance in the White House.

In addition to his long career in military music, Loving also worked with the U.S. Army's intelligence division during World War I, and, in private life, as a real estate investor in the San Francisco Bay area. Toward the end of his life he returned to the Philippines. Loving was killed in 1945 during the Battle of Manila in dramatic, though unclear, circumstances. He posthumously received the Philippines' Presidential Merit Award.

Early life and education

editBorn outside Lovingston, Virginia in 1872, Loving was the son of a former slave. He spent his early childhood living with his parents and an extended family of fourteen relatives. At age ten, Loving moved to Minnesota and into the home of Charles Eugene Flandrau, who employed Loving's sister Julia as a maid. He and Julia later relocated with the Flandrau family to South Dakota. Family legend claims Loving was tutored in mathematics by Theodore Roosevelt when the future president stayed at the Flandrau home in 1886. According to Loving's biographer Robert Yoder, Loving may have viewed Flandrau as a sort-of father figure. It is known that he attended elementary school with Flandrau's son, Charles Macomb Flandrau, and believed that Flandrau financed Loving's later education at the Preparatory High School for Negro Youth in Washington, DC and, subsequently, the New England Conservatory of Music.[1]

Loving's early adulthood involved several stints in the U.S. Army as a musician, and later regimental bandleader. A later period of study at the New England Conservatory of Music ended when Loving decided to rejoin the Army over the protests of his professors, who believed his talent as a cornetist would be wasted. After withdrawing from the conservatory, Loving was given command of the band of the 45th United States Volunteer Infantry Regiment.[1]

Career

editPhilippine Constabulary Band

editIn 1902 Loving was tapped to organize the Philippine Constabulary Band on the recommendation of Governor-General of the Philippines William Howard Taft, who had earlier heard Loving's 45th regimental band perform. Loving, who had learned both Spanish and Tagalog during his brief time in the Philippines, developed an instant rapport with his bandsmen.[2] During the period in which Loving led the Philippine Constabulary Band it established a reputation for excellence both in the Philippines and the United States.[2] The band performed at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, where it was awarded First Prize in competition against other leading military bands.[3] The U.S. military periodical Army and Navy Life described the band as "one of the finest of all military bands in the world," while the Pacific Coast Musical Review, opined that "the Philippine Constabulary Band is in a class by itself."[4][5][6] During a 1915 performance in San Francisco, California, John Philip Sousa was invited to guest conduct the group, afterwards commenting that, "when I closed my eyes, I thought it was the United States Marine Band."[6]

The Philippine Constabulary Band was the lead unit in the United States presidential inaugural parade of 1909, which saw its former patron William Howard Taft inaugurated as President of the United States. It was the first time a band other than the United States Marine Band served as the musical escort to the President of the United States.[7][8]

The day after the inauguration the band was invited to perform for the president and Mrs. Taft at the White House, becoming the first band in history from outside the continental United States to perform at a White House reception.[6] It is also believed this may have been the first time an African American conducted a musical performance at the White House.[6]

Loving continued as the band's director until being forced to take a medical leave in 1915 due to tuberculosis.[1]

Military Intelligence Division

editDuring World War I Loving served stateside in the U.S. Army as an officer in the Military Intelligence Division. Holding the rank of major throughout the war, Loving was initially charged with investigating subversive activities by African American leaders, attending meetings and rallies in plainclothes and developing a network of informants. In one of his reports he would assert that African American socialists were "the most radical of all radicals" as well as allege "vicious and well-financed propaganda" campaigns run in black newspapers as being the impetus for the Chicago race riot of 1919.[9] David Levering Lewis has called Loving "one of the Army's most effective wartime undercover Negro agents."[10]

Later, Loving would be tasked with touring the United States to inspect the conditions of race relations at U.S. Army camps. His final report observed that African American soldiers were best treated and most effectively integrated into military units when white officers from the western United States and northeastern United States held command and he recommended to the Army that white officers from the southern United States not be permitted to lead units with black soldiers. Loving also attacked the Army's racial policies pertaining to non-commissioned officers, noting that,[9][11]

"The assignment of white noncommissioned officers to colored units is a new departure in the history of the American army. Even in Civil War days colored units carried colored noncommissioned officers ... that most of these white noncommissioned officers view themselves in the light of the overseer of antebellum days is shown by their practice of carrying revolvers when they take details of men out to work."

Return to Manila and second retirement

editFollowing the end of hostilities, Loving returned to the Philippines and resumed command of the Philippine Constabulary Band for three years before retiring a second time, moving with his wife, Edith, to Oakland, California.[2] In Oakland, Loving found success in real estate speculation. Because attitudes in Oakland at the time made African American ownership of property in some portions of the city problematic, Loving would dress in a chauffeur's uniform and drive Edith, who had a light complexion and could be mistaken for Caucasian, to view property.[1]

Later career and third retirement

editFrom 1937 through 1940, Loving again took command of the Philippine Constabulary Band, by then renamed the Philippine Army Orchestra. Returning to the Philippines at the personal invitation of Manuel Quezon, he was commissioned at the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Philippine Commonwealth Army and also made "Special Advisor to the President of the Philippines." He retired in 1940 but continued to live in Manila.[2] According to an obituary in the Chicago Tribune penned by Loving's longtime friend Roscoe Simmons, "Col. Loving and Gen. MacArthur had an affectionate relationship known in all military circles" and MacArthur would later recall Loving's death as "a sacrifice he would never forget."[12]

Death

editWalter and Edith Loving were detained in 1941 by Japanese forces following the surrender of Manila. During his captivity, Loving composed a resistance song Beloved Philippines. He was released due to his declining health and advancing age in 1943. In 1945, during the Battle of Manila, Loving was again arrested and detained, along with other Americans and Filipinos, at the Manila Hotel.[1]

The exact circumstances surrounding Loving's death are unclear. According to Yoder, with Manila's defenses on the verge of collapse to the advancing American and Filipino armies, the hotel prisoners were ordered to run to the beach while Japanese soldiers shot at them. The then 72-year-old Loving refused to run, declaring "I am an American. If I must die, I'll die like an American," whereupon he was beheaded.[1] In a 2010 article, a Philippine newspaper columnist contends, however, the Manila Hotel prisoners attempted escape and Loving used his body to barricade a staircase to prevent Japanese troops from pursuit; he was bayoneted to death in the process.[13] A third account relayed in a 1945 Associated Negro Press story says that Loving was shot in the back by retreating Japanese troops. Mortally wounded, he crawled from the Manila Hotel to the battered bandstand at Luneta Park, the site of many of the Philippine Constabulary Band's performances, and died.[14]

In 1952, Loving was posthumously awarded the Presidential Merit Medal by the Government of the Philippines during a ceremony at Luneta during which his final composition, Beloved Philippines, was performed.[15] Loving was also the recipient of the Distinguished Conduct Star, the second-highest military honor of the Philippines, and the United States' Philippine Campaign Medal, the latter given for his service during the Philippine–American War.[2][16]

Personal life

editLoving married his wife, Edith, in 1916 and had one son, Walter.[1] Walter Loving Jr.'s godfather was Roscoe Simmons.[12]

During the course of his life, Loving took an interest in politics, supporting both Republican and Democratic candidates. During the 1916 United States presidential election, Loving requested his former patron, Taft, introduce him to Republican presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes, with whose campaign he sought to volunteer. Taft, however, declined in a letter, explaining he did not feel it was appropriate for him to offer such an introduction to a political candidate (in that letter, Taft also expressed to Loving his regret that "you are no longer at the head of the Constabulary Band which was largely your creation.") Loving also campaigned for Isabella Selmes Greenway, the granddaughter of Charles Flandrau, during her 1932 congressional race in Arizona.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Yoder, Robert (2013). In Performance: Walter Howard Loving and the Philippine Constabulary Band. National Historic Commission of the Philippines. pp. 12–15, 32, 40–46, 48. ISBN 978-9715382595.

- ^ a b c d e Cunningham, Roger (Summer 2007). "The Loving Touch" (PDF). Army History. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Band Leader Loving Gets O. R. C. Commission". New Journal and Guide. October 1924 – via ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Black Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Walker, David (20 March 1915). "Philippine Constabulary Band Concert". Pacific Coast Musical Review. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Army and Navy Life, vol. 14. 1909. p. 286. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Michael. "Reports of Research in Music Education Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Texas Music Educators Association San Antonio, Texas, February, 2004" (PDF). tmea.org. Texas Music Educators Association. pp. 17–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Handy, Antoinette (1999). Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras. Scarecrow. p. 19. ISBN 0810834197.

- ^ Hila, Antonio (11 March 2013). "Believe it or not, a Philippine band had taken part in a US presidential inaugural". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ a b Jordan, William (2001). Black Newspapers and America's War for Democracy, 1914–1920. University of North Carolina Press. p. 137. ISBN 0807849367.

- ^ Lewis, David (2001). W. E. B. Du Bois, 1919–1963: The Fight for Equality and the American Century. Holt. p. 7. ISBN 0805068139.

- ^ Williams, Chad (2010). Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0807899359.

- ^ a b Simmons, Roscoe (4 April 1948). "The Untold Story". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Alcazaren, Paoulo (4 December 2010). "Loving's band". Philippine Star. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Loeb, Charles (14 April 1945). "Eyewitness Tells How Famous Bandleader Was Slain by Japs". The Afro-American. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Walsh, Timothy (2013). Tin Pan Alley and the Philippines: American Songs of War and Love, 1898–1946 ... Rowman & Littlefield. p. 11. ISBN 978-0810886087.

- ^ "View the Roll of Honor" (PDF). gov.ph. Government Gazette of the Philippines. Retrieved 1 October 2015.