Wahkare Khety was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 9th or 10th Dynasty during the First Intermediate Period.

| Wahkarê Khety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achthoês,[1] Khety III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

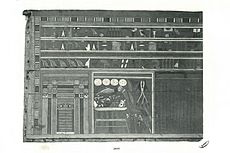

Outer coffin of the steward Nefri, on which the cartouches of Wahkare Khety were found (Cairo CG 28088) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | c. 50 years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | possibly Qakare Ibi or Wadjkare (if 9th Dynasty); Neferkare VIII (if 10th Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | uncertain (if 9th Dynasty); Merikare (if 10th Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Merikare? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 9th or 10th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Identity

editThe identity of Wahkare Khety is controversial. While some scholars believe that he was the founder of the 9th Dynasty,[2] many others place him in the subsequent 10th Dynasty.[3][4][5][6]

9th Dynasty hypothesis

editIf Wahkare Khety was the founder of the 9th Dynasty, he may be identified with the hellenized king Achthoês, the founder of this dynasty according to Manetho. Manetho reports:

The first of these [kings], Achthoês, behaving more cruel than his predecessors, wrought woes for the people of all of Egypt, but afterwards he was smitten with madness and killed by a crocodile.[1][7]

If this hypothesis is correct, Wahkare Khety may have been a Herakleopolitan prince who profited from the weakness of the Memphite rulers of the Eighth Dynasty to seize the throne of Middle and Lower Egypt around 2150 BC. This hypothesis is supported by contemporary inscriptions referring to the northern, Herakleopolitan kingdom as the House of Khety,[8] although that only proves that the founder of the 9th Dynasty was a Khety, but not necessarily Wahkare Khety.

10th Dynasty hypothesis

editMany scholars believe instead that Wahkare Khety was a king of the 10th Dynasty, identifying him with the Khety, who was the alleged author of the famous Teaching for King Merykare, thus placing him between Neferkare VIII and Merikare. In this reconstruction, Wahkare is the last Herakleopolitan king bearing the name Khety, and the cruel Achthoês founder of the 9th Dynasty is identified with Meryibre Khety, and the House of Khety must refer to him instead.

From the Instructions, it is known that Wahkare Khety, in alliance with the nomarchs of Lower Egypt, managed to repel the nomad "Asiatics" who for generations roamed in the Nile Delta. Those nomarchs, although recognizing Wahkare's authority, ruled de facto more or less independently. The expulsion of the "Asiatics" allowed the establishment of new settlements and defense structures on the northeastern borders, as well as the reprise of trades with the Levantine coast.[9] Wahkare, however, warned Merikare not to neglect guarding these borders, as the "Asiatics" still were considered a danger.[10]

In the south, Wahkare and the faithful nomarch of Asyut Tefibi retook the city of Thinis, previously captured by the Thebans led by Intef II; however, the troops of Herakleopolis sacked the sacred necropolis of Thinis, a serious crime which was reported by Wahkare himself. This crime caused the immediate reaction of the Thebans, who later finally captured the Thinite nomos. After those events Wahkare Khety decided to abandon this bellicose policy and begin a phase of peaceful coexistence with the southern kingdom, which endured until part of the reign of his successor Merikare, who succeeded the long reign – five decades – of Wahkare.[11]

Attestations

editThere is no contemporary evidence bearing his name. His cartouches appears on a 12th Dynasty wooden coffin inscribed with Coffin Texts and originally made for a steward named Nefri, was found in Deir el-Bersha and now is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (CG 28088).[12][13] On it, Wahkare Khety's name was found once in place of Nefri's, but it is unknown if the texts were originally inscribed for the king, or if they were simply copied later from an earlier source.[14] His name is maybe also attested in the Royal canon of Turin.[14]

References

edit- ^ a b William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (= The Loeb classical library. Bd. 350). Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 2004 (Reprint), ISBN 0-674-99385-3, p. 61.

- ^ Jürgen von Beckerath, Handbuch der Ägyptischen Königsnamen, 2nd edition, Mainz, 1999, p. 74.

- ^ William C. Hayes, in The Cambridge Ancient History, vol 1, part 2, 1971 (2008), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-077915, p. 996.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford, Blackwell Books, 1992, p. 144–47.

- ^ Michael Rice, Who is who in Ancient Egypt, 1999 (2004), Routledge, London, ISBN 0-203-44328-4, p. 7.

- ^ Margaret Bunson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 1438109970, p. 202.

- ^ Margaret Bunson, op. cit., p. 355.

- ^ Stephan Seidlmayer, Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7, p. 128.

- ^ William C. Hayes, op. cit., p. 466.

- ^ William C. Hayes, op. cit., p. 237.

- ^ William C. Hayes, op. cit., pp. 466–67.

- ^ Pierre Lacau, Sarcophages antérieurs au Nouvel Empire, tome II, Cairo, 1903, pp. 10–20.

- ^ Alan Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, an introduction. Oxford University Press 1961, p. 112

- ^ a b Thomas Schneider, Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3, p. 172.

Further reading

edit- Allen, James P. (1976). "The Funerary Texts of King Wahkare Akhtoy on a Middle Kingdom Coffin". In Johnson, J. H.; Wente, E. F. (eds.). Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, January 12, 1977. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization (SAOC). Vol. 39. Chicago: The Oriental Institute. ISBN 0-918986-01-X.