Viktor Hermann Brack (9 November 1904 – 2 June 1948) was a member of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and a convicted Nazi war criminal and one of the prominent organisers of the involuntary euthanasia programme Aktion T4; this Nazi initiative resulted in the systematic murder of 275,000 to 300,000 disabled people. He held various positions of responsibility in Hitler's Chancellery in Berlin. Following his role in the T4 programme, Brack was one of the men identified as responsible for the gassing of Jews in extermination camps, having conferred with Odilo Globočnik about its use in the practical implementation of the Final Solution. Brack was sentenced to death in 1947 in the Doctors' Trial and executed by hanging in 1948.

Viktor Brack | |

|---|---|

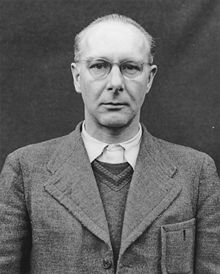

Brack's photograph for the Nuremberg trial | |

| Born | Viktor Hermann Brack 9 November 1904 |

| Died | 2 June 1948 (aged 43) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Occupation(s) | Chief of Office II: Affairs of the Party, State, and the Armed Forces in the Chancellery of the Führer of the NSDAP |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Motive | Nazism |

| Conviction(s) | War crimes Crimes against humanity Membership in a criminal organization |

| Trial | Doctors' trial |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

Early life and Nazi Party membership

editBrack was born the son of a physician in Haaren (now part of Aachen) in the Rhine Province.[1] In 1928, he completed a degree in agriculture at the Technical University of Munich and shortly thereafter began managing the estate attached to his father's sanatorium; he also was a test driver for BMW.[1]

In 1929 at the age of 25, Brack became a member of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the Schutzstaffel (SS). Throughout 1930 and 1931, Brack was one of Heinrich Himmler's personal drivers, having become acquainted with the Reichsführer-SS as a consequence of his father having delivered one of the SS leader's children.[1] Sometime in 1932, he became adjutant to Philipp Bouhler and by 1934, Brack was his chief of staff.[2] In 1936, he was appointed chief of Hauptamt II (main office II) in the Chancellery of the Führer in Berlin.[3] The office handled matters concerning the Reich Ministries, Wehrmacht, NSDAP, clemency petitions and complaints received by the Führer from all parts of Germany.[4]

Aktion T4

editHauptamt II officials under Viktor Brack played a vital role in organising the killing of mentally ill and physically handicapped people in the Aktion T4 "euthanasia" programme, especially the child "euthanasia" from 1939.[5] By a (backdated) decree of 1 September,[6] Hitler appointed Philipp Bouhler and his personal physician Karl Brandt to manage the euthanasia program, where they would oversee the murder of physically and/or mentally disabled persons.[7] The implementation of the killing operations was left to subordinates such as Brack[8] and SA-Oberführer Werner Blankenburg.[9][a] To efficiently accomplish this task, Brack, who headed Office II of the Führer's Chancellery created four offices; these were Office IIa or the Deputy Chief of Central Office II, headed by Blankenburg ; Office IIb, led by Hans Hefelmann, which dealt with the Reich government and clemency petitions; Office IIc, overseen by Reinhold Vorberg, responsible for matters related to the armed forces, the police, the SS, and churches; and Office IId for matters concerning the Nazi Party, which was headed by Amtsleiter Buchholz and then by Dr. Brümmel.[11]

In January 1940, Brack gave August Becker the task of arranging gas-killing operations of mentally ill patients and other people whom the Nazis deemed "life unworthy of life".[12] The Aktion T4 program was related to popular early 20th-century ideas of eugenics and improving the race, not allowing disabled or mentally ill people to reproduce. Initially, the doctors in the program sterilized people, but then they murdered nearly 15,000 German citizens at Hadamar Euthanasia Centre under an extension of this program.[13][b]

On 3 April 1940, Brack explained to leading members of the German Council of Municipalities his justification for murdering persons deemed permanently mentally ill.[14] Among material considerations, Brack outlined how they "deprived" others of food (useless eaters), and unnecessarily took up space at hospitals for otherwise curable people.[14] Beyond those reasons, Brack added the ideological components of racial hygiene as grounds for their extermination, atop stressing the importance of the war effort above humanitarian factors.[15]

There were six principal killing centers; these resided at Hartheim, Sonnenstein, Grafeneck, Bernburg, Brandenburg, and Hadamar; most of which, historian Robert Lifton points out, "were in isolated areas and had high walls—some had originally been old castles—so that what happened within could not be readily observed from without."[16] Given the scale of the operation, Brack recruited personnel using his network of contacts and party connections to fully staff T4,[c] none of whom were forced to participate but volunteered their services.[18] The T4 killings took place from September 1939 until the end of the war in 1945; from 275,000 to 300,000 people were killed in psychiatric hospitals in Germany and Austria, occupied Poland and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (now the Czech Republic).[19][20][21]

Role in the Holocaust

editDuring October 1941, Adolf Eichmann and Brack decided to begin using "gas vans" to murder Jews incapable of working, the first three of which were set up at Chełmno extermination camp.[22] Not only did the Einsatzgruppen mobile units assigned there kill Jews, but they also gassed Gypsies, people suffering from typhus, Soviet POWs, and the insane; all of whom were led into the vans, murdered, and then driven to nearby woods so their bodies could be placed in mass graves.[22] On 23 June 1942 Brack wrote the following letter to Himmler:

Dear Reichsführer, among tens of millions of Jews in Europe, there are, I figure, at least two to three millions of men and women who are fit enough to work. Considering the extraordinary difficulties the labour problem presents us with, I hold the view that those two to three millions should be specially selected and preserved. This can, however, only be done if at the same time they are rendered incapable to propagate.[23]

Brack only intended to spare these 2–3 million Jews capable of work provided they were accordingly sterilized.[24] Following these recommendations, Himmler ordered the procedure to be tested on prisoners in Auschwitz. Since Brack was transferred to an SS division, his deputy Blankenburg took over responsibility for the task and would "immediately take the necessary measures and get in touch with the chiefs of the main offices of the concentration camps".[25] When sterilization proved impracticable, this was rejected in favor of exterminating the Jews using poison gas, since the technical apparatus was already in place via T4 to kill unwanted "mentally ill" persons.[26] With the completion of the T4 euthanasia programme run by Brack, the Nazis dismantled the gas chambers previously used for that endeavor, shipped them east, and reinstalled them at Majdanek, Auschwitz, and Treblinka.[27] Brack subsequently took part in the administrative process of establishing extermination camps in occupied Poland.[28] It was personnel and equipment provided by Brack that were utilized to murder the Jews.[29][d]

Trial and execution

editSometime in April 1945, Viktor Brack and his superior Phillip Bouhler were arrested.[30] During the Eichberg trial,[e] which concluded at Frankfurt on 21 December 1946, Brack was implicated for his role in recruiting physicians for the euthanasia killings.[31] At the Hadamar Trial—between 24 February 1947 until 21 March 1947—he was again implicated along with Dr. Karl Brandt for his involvement in the T4 programme.[31] Brack was known to radically enforce euthanasia, even terrorizing doctors and nurses to ensure they maintained the killing procedures, despite later claiming during the trials that he had never even heard of the T4 programme.[32]

During the trials, Brack insisted that euthanasia was a "humane measure" for incurably sick people and denied all knowledge of the Holocaust.[33] He contested his complicity in mass X-ray sterilizations until confronted by his signature on corresponding documents; meanwhile other administrators—Rudolf Brandt and Wolfram Sievers—testified against Brack, proving links between him, the Führer's Chancellery, and Hitler.[34] Nonetheless, Brack denied any anti-Semitism or involvement with killing Jews and avowed that he had joined the Waffen-SS in 1942 to distance himself from the regime.[35]

On 20 August 1947, Brack was sentenced to death.[36] He was executed by hanging at Landsberg Prison on 2 June 1948, stating at the gallows that he "wished for God to give peace to the world."[36]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ In his role as an administrator of the T4 programme, Brack was codenamed "Jennerwein".[10]

- ^ Also see: Vernehmungsprotokoll der Sonderkommission des Hessischen Landeskriminalamtes Wiesbaden, V/1, April 4, 1960, "Tötung in einer Minute". „Mitschrift der Vernehmung und Fahndungsschreiben von Dr. phil. August Becker“ (in German)

- ^ As the liaison between the Führer's Chancellery and the Health Ministry, historian David Cesarini claims that it was Brack, who "developed the organization."[17]

- ^ While historians Robert Jay Lifton and Henry Friedlander assert that the T4 programme provided the "medical bridge to genocide" and were part of Nazi Germany's first "mass murder," Cesarini was not so convinced, arguing instead that it was Einsatzgruppen operations in Poland—particularly Operation Tannenberg—that formed the "bridge to genocide" and not compulsory euthanasia.[29]

- ^ This proceeding was one among a series in the Doctors' trial

Citations

edit- ^ a b c Friedlander 1995, p. 68.

- ^ Stackelberg 2007, p. 186.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Schafft 2004, pp. 159–163.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Schafft 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Proctor 1988, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 141.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Proctor 1988, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 71, 73–75, 100.

- ^ a b Kay 2021, p. 34.

- ^ Kay 2021, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 71.

- ^ Cesarani 2016, p. 282.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, p. 69.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 477.

- ^ Browning 2005, p. 193.

- ^ Proctor 1988, p. 191.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 79.

- ^ Friedmann 1977, p. 6.

- ^ Proctor 1988, p. 206.

- ^ International Military Tribunal 1949, p. 279.

- ^ Proctor 1988, p. 207.

- ^ Michalczyk 1994, p. 39.

- ^ Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 106.

- ^ a b Cesarani 2016, p. 286.

- ^ Weindling 2004, p. 34.

- ^ a b Weindling 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Weindling 2004, pp. 222, 256.

- ^ Weindling 2004, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Weindling 2004, pp. 159, 173.

- ^ Weindling 2004, p. 253.

- ^ a b Weindling 2004, p. 302.

Bibliography

edit- Browning, Christopher (2005). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Arrow. ISBN 978-0-8032-5979-9.

- Cesarani, David (2016). Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–1945. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-1-25000-083-5.

- Friedlander, Henry (1995). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80782-208-1.

- Friedmann, Towish, ed. (1977). Himmlers Teufels: General SS- und Polizeiführer Globoćnik in Lublin und Ein Bericht über die Judenvernichtung im General-Gouvernement in Polen 1941–1944, Dokumenten-Sammlung (in German). Haifa: Institute of Documentation in Israel for the Investigation of Nazi War Crimes. OCLC 654617673.

- Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 0-8419-0910-5.

- International Military Tribunal (1949). Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10, Nuernberg, October 1946-April 1949. Vol. 2. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 62569816.

- Kay, Alex J. (2021). Empire of Destruction: A History of Nazi Mass Killing. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-26253-7.

- Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-46504-905-9.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Michalczyk, John J. (1994). Medicine, Ethics, and the Third Reich: Historical and Contemporary Issues. Kansas City, MO: Sheed & Ward. ISBN 978-1-55612-752-6.

- Proctor, Robert (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674745780.

- Schafft, Gretchen E. (2004). From Racism to Genocide: Anthropology in the Third Reich. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-25207-453-0.

- Stackelberg, Roderick (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41530-861-8.

- Weindling, Paul J. (2004). Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials: From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23050-700-5.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1991). The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: MacMillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-897500-6.