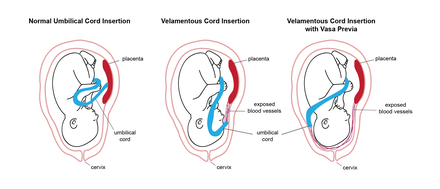

Velamentous cord insertion is a complication of pregnancy where the umbilical cord is inserted in the fetal membranes. It is a major cause of antepartum hemorrhage that leads to loss of fetal blood and associated with high perinatal mortality. In normal pregnancies, the umbilical cord inserts into the middle of the placental mass and is completely encased by the amniotic sac. The vessels are hence normally protected by Wharton's jelly, which prevents rupture during pregnancy and labor.[10] In velamentous cord insertion, the vessels of the umbilical cord are improperly inserted in the chorioamniotic membrane, and hence the vessels traverse between the amnion and the chorion towards the placenta.[1][11] Without Wharton's jelly protecting the vessels, the exposed vessels are susceptible to compression and rupture.[1][9]

| Velamentous cord insertion | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Velamentous Placenta |

| |

| Normal umbilical cord insertion and velamentous umbilical cord insertion in pregnancy, with and without vasa previa. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Symptoms | Blood vessel compression,[1][2] decrease in blood supply to the fetus,[2][3] impaired growth and development of the fetus.[4][5] |

| Risk factors | Multiple gestation,[1][2][6][7][8] placental anomalies [9] previous pregnancy with abnormal cord insertion[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Abdominal ultrasound[3][4] |

| Treatment | Caesarean section[7] |

| Frequency | 0.1%-1.8% of pregnancies[6] |

The exact cause of velamentous cord insertion is unknown, although risk factors include nulliparity,[2][6] the use of assisted reproductive technology,[6][12] maternal obesity,[6][7] and pregnancy with other placental anomalies.[9] Velamentous cord insertion is often diagnosed using an abdominal ultrasound.[3][4] This is most successful in the second trimester,[13] however Color Doppler ultrasound[14] or transvaginal ultrasound[15] can be used in difficult cases, such as when the placenta is located posteriorly. If the woman is diagnosed with velamentous cord insertion, the pregnancy is closely monitored, especially as velamentous cord insertion is a strong risk factor for vasa previa, where the exposed vessels cross the cervix and are at high risk of rupture during membrane rupture in early labor.[9] Management strategies for velamentous cord insertion also involve determining the presence of vasa previa.[16] Velamentous cord insertion impacts fetal development during pregnancy by impairing the development of the placenta[2] and modifying the efficiency of placental function.[17] This can manifest in a range of adverse perinatal outcomes, such as fetal growth restriction,[4][5] placental abruption,[3][6][16][18] abnormal fetal heart rate patterns,[3][10][19] and fetal death.[6][7][9] Velamentous cord insertion affects between 0.1%-1.8% of pregnancies,[6] though its incidence increases ten-fold in multiple pregnancies.[1][10]

Signs and symptoms

editSigns and symptoms of velamentous cord insertion during pregnancy include blood vessel compression,[1][2] decrease in blood supply to the fetus,[2][3] and impaired growth and development of the fetus.[4][5] Blood tests taken in the second trimester may reveal increased levels of serum human chorionic gonadotropin and reduced levels of alpha-fetoprotein.[20][21] The mother may also experience vaginal bleeding, particularly in the third trimester.[11] Women with velamentous cord insertion may not experience any symptoms throughout pregnancy.[16] During delivery, there may be slow or abnormal fetal heart rate patterns[3][10][19] and there may be excessive bleeding or hemorrhage, particularly if the fetal vessels rupture.[1][7][9][22]

Pathophysiology

editThe exact mechanisms leading to insertion of the umbilical cord in the fetal membranes are unknown, although they are likely to occur in the first trimester.[23] One theory is that velamentous cord insertion may arise from the process of placental trophotropism, which is the phenomenon where the placenta migrates towards areas which have better blood flow with advancing gestation. The placenta grows in regions with better blood supply and portions atrophy in regions of poor blood flow. This process of atrophy may result in the exposure of umbilical blood vessels, causing marginal or peripheral placental insertion to evolve to velamentous insertion over time.[1][10][23]

Placentas with velamentous cord insertion have a lower vessel density.[2] As the growth of the fetus is dependent on the organization, mass, and nutrient-transfer capacity of the placenta, fetal development is hence hindered in velamentous cord insertion. This can lead to fetal malformations[2][24] and low birth weight.[2][6][10] The umbilical vessels may also be longer compared to normal,[2] particularly when the site of velamentous cord insertion is in the lower uterine section as the extension of the uterine isthmus as pregnancy advances causes vessel elongation.[3] This results in increased vascular resistance, which impedes nutrient transfer to the fetus.[2]

The umbilical vessels experience increased pressure and compression as they are not protected by Wharton's jelly. This can cause decreased or acute cessation of blood flow, decreased cardiac output, and pulmonary complications in the newborn.[2] The elongated, exposed vessels in lower velamentous cord insertion cases are more readily compressed by the fetus, hence there is an even greater risk of non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern and emergency caesarean section.[2][3]

The growth-restricting impacts of placental insufficiency resulting from velamentous cord insertion can also augment the effects of increased pressure to the umbilical vessels.[2] Normally in the second half of pregnancy, one-third of fetal cardiac output is directed towards the placenta. This fraction is reduced to around one-fifth in the last few weeks of pregnancy, while the remaining umbilical blood is recirculated in the fetal body, corresponding with decreased fetal reserves of oxygen.[25] In pregnancies with growth restriction, the fraction of fetal cardiac output distributed to the placenta decreases, further lowering fetal reserves.[2][25] This can result in increased risk of caesarean delivery, fetal hypoxia, and perinatal death in pregnancies with velamentous cord insertion.[2]

Damage to the umbilical cord vessels can occur when the amniotic membranes are ruptured, particularly in the case of vasa previa, potentially leading to fetal exsanguination.[3][8][26] If the umbilical vessels are positioned such that their rupture is likely during labor, an elective operative birth at 35–36 weeks gestation may be planned, and corticosteroids may be administered in order to assist with fetal lung maturation.[7][9] Overall, velamentous cord insertion doubles the risk of both preterm birth and acute caesarean section.[2]

Risk factors

editThe following have been identified as risk factors for velamentous cord insertion:

- Nulliparity[2][6]

- History of infertility[6]

- The use of assisted reproductive technology[6][7][12]

- Multiple gestation[1][2][6][7][8]

- Maternal smoking[1][2][6][7]

- Maternal asthma[2]

- Maternal obesity[6]

- Chronic hypertension[2]

- Type 1 diabetes[2]

- Gestational diabetes[2]

- Placental anomalies, including low-lying placenta, bilobed placenta, placenta with accessory lobe/s[9]

- Previous pregnancy with abnormal cord insertion[2]

- Having an umbilical cord with a single umbilical artery[9]

- Advanced maternal age[5][27]

Diagnosis

editAbdominal ultrasound can be used to visualize the insertion site of the umbilical cord.[3][4] Overall, visualization is most successful in the second trimester,[13] however routine ultrasound examination in the second trimester may not detect velamentous cord insertion if the condition develops after the remodelling of the placenta as gestation advances.[10] Visualization becomes increasingly difficult in the third trimester as the fetus may obscure the insertion site.[4][13]

The umbilical cord and its insertion site may be obscured by the fetus, such as in posterior placenta or in low-lying placenta, or may be difficult to visualise due to conditions such as maternal obesity.[10][15] In these cases, the use of Color Doppler ultrasound or transvaginal ultrasound can enhance the visualization of the umbilical cord, and are able to diagnose velamentous cord insertion at 18–20 weeks.[14][15]

Management

editIf velamentous cord insertion is diagnosed, fetal growth is assessed every four weeks using ultrasound beginning at 28 weeks. If intrauterine growth restriction is observed, the umbilical cord is also assessed for signs of compression. Non-stress tests may be performed twice a week to ensure adequate blood flow to the fetus.[16] The amniotic fluid may be frequently assessed for high levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 which can indicate intra-amniotic inflammation.[28][29]

Upon diagnosis of velamentous cord insertion, transvaginal ultrasound with Color Doppler may also be performed to determine whether any of the exposed vessels are within two centimeters (or five centimeters, a more common threshold recently) of the internal cervical os. If such vessels are identified, vasa previa may be present and cervical length is measured every week to determine the risk of premature rupture of membranes.[16]

Women diagnosed with velamentous cord insertion may also receive counselling about the condition, its risks, and potential courses of action, including preterm delivery or caesarean delivery.[7]

The newborn may be delivered via normal vagina labor if there are no signs of fetal distress.[2] Fetal heart rate is continuously monitored for slow or abnormal heart rate patterns which may indicate fetal distress during labor.[7] If the exposed blood vessels are near the cervix or are at risk of rupturing, the newborn may be delivered via caesarean section as early as 35 weeks gestation.[7][9]

Complications

editMaternal

edit- Vasa previa[2][3][7][11][16]

- Rupture of the vessels and membranes[1][7][9]

- Small placenta[2]

- Low arterial cord pH[10]

- Vascular thrombosis[9]

- Intrapartum bleeding[11]

- Umbilical cord avulsion[10][27]

- Need for caesarean delivery,[2][3] curettage,[22] manual extraction of the placenta[1][27]

- Placental abruption[3][6][16][18]

- Postpartum hemorrhage[1][7][9][22]

Fetal

edit- Prematurity[2][4]

- Abnormal heart rate patterns[3][10][19]

- Low birth weight[2][6][10]

- Newborn/s small for gestational age[4][5][6]

- Low Apgar score[3][4][10]

- Fetal hypoxia[9][23]

- Pulmonary complications[2]

- Fetal malformations[1][2]

- Fetal bleeding[9][4]

- Death[3][5][6][7][9][10]

In twins, one or both of the fetuses may have velamentous cord insertion, which can lead to birth-weight discordance, where one twin weighs significantly more at birth than the other,[2][30] and selective fetal growth restriction.[31] These complications particularly arise in the case of monochorionic twins, where identical twins share the same placenta.[2][32]

Epidemiology

editVelamentous cord insertion occurs in between 0.1%-1.8% of all pregnancies,[6] and is eight to ten times more frequent in multiple pregnancies.[1][3][12] This risk is doubled in the case of monochorionic twins, and tripled in the case of fetal growth restriction.[1] It is thought that sex may be a determinant of abnormal cord insertions, however there is conflicting evidence as to whether male or female fetuses are linked to greater risk of velamentous cord insertion.[2][6]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ismail K, Hannigan A, ODonoghue K, Cotter A (2017). "Abnormal placental cord insertion and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Systematic Reviews. 6 (1): 242. doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0641-1. PMC 5718132. PMID 29208042.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Ebbing C, Kiserud T, Johnsen S, Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S (2013). "Prevalence, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Velamentous and Marginal Cord Insertions: A Population-Based Study of 634,741 Pregnancies". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e70380. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870380E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070380. PMC 3728211. PMID 23936197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Hasegawa J, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Sekizawa A, Okai T (2006). "Velamentous Cord Insertion: Significance of Prenatal Detection to Predict Perinatal Complications". Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 45 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60185-6. PMID 17272203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sepulveda W, Rojas I, Robert J, Schnapp C, Alcalde J (2003). "Prenatal detection of velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord: a prospective color Doppler ultrasound study". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 21 (6): 564–569. doi:10.1002/uog.132. PMID 12808673. S2CID 1788491.

- ^ a b c d e f Eddleman K, Lockwood C, Berkowitz G, Lapinski R, Berkowitz R (1992). "Clinical Significance and Sonographic Diagnosis of Velamentous Umbilical Cord Insertion". American Journal of Perinatology. 9 (2): 123–126. doi:10.1055/s-2007-994684. PMID 1590867. S2CID 39286973.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Räisänen S, Georgiadis L, Harju M, Keski-Nisula L, Heinonen S (2012). "Risk factors and adverse pregnancy outcomes among births affected by velamentous umbilical cord insertion: a retrospective population-based register study". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 165 (2): 231–234. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.08.021. PMID 22944380.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wiedaseck S, Monchek R (2014). "Placental and Cord Insertion Pathologies: Screening, Diagnosis, and Management". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 59 (3): 328–335. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12189. PMID 24751147.

- ^ a b c Furuya S, Kubonoya K, Kubonaya K (2014). "Prevalence of velamentous and marginal umbilical cord insertions; a comparison of term singleton ART and non-ART pregnancies". Fertility and Sterility. 102 (3): e313. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.07.1063.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Bohiltea R, Cirstoiu M, Ciuvica A, Munteanu O, Bodean O, Voicu D, Ionescu C (2016). "Velamentous insertion of umbilical cord with vasa praevia: case series and literature review". Journal of Medicine and Life. 9 (2): 126–129. PMC 4863500. PMID 27453740.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sinkin J, Craig W, Jones M, Pinette M, Wax J (2018). "Perinatal Outcomes Associated With Isolated Velamentous Cord Insertion in Singleton and Twin Pregnancies". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 37 (2): 471–718. doi:10.1002/jum.14357. PMID 28850682. S2CID 26888548.

- ^ a b c d Paavonen J, Jouttunpää K, Kangasluoma P, Aro P, Heinonen P (1984). "Velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord and vasa previa". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 22 (3): 207–211. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(84)90007-9. PMID 6148278. S2CID 23409481.

- ^ a b c Delbaere I, Goetgeluk S, Derom C, De Bacquer D, De Sutter P, Temmerman M (2007). "Umbilical cord anomalies are more frequent in twins after assisted reproduction". Human Reproduction. 22 (10): 2763–2767. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem191. hdl:1854/LU-373160. PMID 17720701.

- ^ a b c Pretorius D, Chau C, Poeltler D, Mendoza A, Catanzarite V, Hollenbach K (1996). "Placental cord insertion visualization with prenatal ultrasonography". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 15 (8): 585–593. doi:10.7863/jum.1996.15.8.585. PMID 8839406. S2CID 40093577.

- ^ a b Nomiyama M, Toyota Y, Kawano H (1998). "Antenatal diagnosis of velamentous umbilical cord insertion and vasa previa with color Doppler imaging". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 12 (6): 426–429. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12060426.x. PMID 9918092. S2CID 35261375.

- ^ a b c Baulies S, Maiz N, Muñoz A, Torrents M, Echevarría M, Serra B (2007). "Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of vasa praevia and analysis of risk factors". Prenatal Diagnosis. 27 (7): 595–599. doi:10.1002/pd.1753. PMID 17497747. S2CID 37634607.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vintzileos A, Ananth C, Smulian J (2015). "Using ultrasound in the clinical management of placental implantation abnormalities". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (4): S70 – S77. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.059. PMID 26428505.

- ^ Yampolsky M, Salafia C, Shlakhter O, Haas D, Eucker B, Thorp J (2009). "Centrality of the Umbilical Cord Insertion in a Human Placenta Influences the Placental Efficiency". Placenta. 30 (12): 1058–1064. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2009.10.001. PMC 2790011. PMID 19879649.

- ^ a b Toivonen S, Heinonen S, Anttila M, Kosma V, Saarikoski S (2002). "Reproductive Risk Factors, Doppler Findings, and Outcome of Affected Births in Placental Abruption: A Population-Based Analysis". American Journal of Perinatology. 19 (8): 451–460. doi:10.1055/s-2002-36868. PMID 12541219. S2CID 259998340.

- ^ a b c Hasegawa J, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Kotani M, Nakamura M, Mikoshiba T, Sekizawa A, Okai (2009). "Atypical variable deceleration in the first stage of labor is a characteristic fetal heart-rate pattern for velamentous cord insertion and hypercoiled cord". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 35 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00863.x. PMID 19215545. S2CID 11157923.

- ^ Heinonen S, Ryynanen M, Kirkinen P, Saarikoski S (1996). "Velamentous umbilical cord insertion may be suspected from maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein and hCG". BJOG. 103 (3): 209–213. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09707.x. PMID 8630303. S2CID 74179289.

- ^ Heinonen S, Ryynanen M, Kirkinen P, Saarikoski S (1996). "Elevated Midtrimester Maternal Serum hCG in Chromosomally Normal Pregnancies is Associated with Preeclampsia and Velamentous Umbilical Cord Insertion". American Journal of Perinatology. 13 (7): 437–441. doi:10.1055/s-2007-994384. PMID 8960614. S2CID 45427947.

- ^ a b c Ebbing C, Kiserud T, Johnsen S, Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S (2015). "Third stage of labor risks in velamentous and marginal cord insertion: a population-based study". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 94 (8): 878–883. doi:10.1111/aogs.12666. PMID 25943426. S2CID 45614777.

- ^ a b c Sepulveda W (2006). "Velamentous Insertion of the Umbilical Cord". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 25 (8): 963–968. doi:10.7863/jum.2006.25.8.963. PMID 16870889. S2CID 43165100.

- ^ Yerlikaya G, Pils S, Springer S, Chalubinski K, Ott J (2015). "Velamentous cord insertion as a risk factor for obstetric outcome: a retrospective case–control study". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 293 (5): 975–981. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3912-x. PMID 26498602. S2CID 1011746.

- ^ a b Kiserud T, Ebbing C, Kessler J, Rasmussen S (2006). "Fetal cardiac output, distribution to the placenta and impact of placental compromise". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 28 (2): 126–136. doi:10.1002/uog.2832. PMID 16826560. S2CID 25954526.

- ^ Robert J, Sepulveda W (2003). "Fetal exsanguination from ruptured vasa previa: still a catastrophic event in modern obstetrics". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 23 (5): 574. doi:10.1080/0144361031000156636. PMID 12963533. S2CID 36906136.

- ^ a b c Esakoff T, Cheng Y, Snowden J, Tran S, Shaffer B, Caughey A (2014). "Velamentous cord insertion: is it associated with adverse perinatal outcomes?". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 28 (4): 409–412. doi:10.3109/14767058.2014.918098. PMID 24758363. S2CID 1390065.

- ^ Kenyon A, Abi-Nader K, Pandya P (2010). "Pre-term pre-labour rupture of membranes and the role of amniocentesis". Fertility and Sterility. 21 (2): 75–88.

- ^ Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Korzeniewski S, Martinez-Varea A, Dong Z, Yoon B, Hassan S, Chaiworapongsa T, Yeo L (2015). "A point of care test for interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: a step toward the early treatment of acute intra-amniotic inflammation/infection". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 29 (3): 360–367. doi:10.3109/14767058.2015.1006621. PMC 5703063. PMID 25758620.

- ^ Kent E, Breathnach F, Gillan J, McAuliffe F, Geary M, Daly S, Higgins J, Dornan J, Morrison J, Burke G, Higgins S, Carroll S, Dicker P, Manning F, Malone F (2011). "Placental cord insertion and birthweight discordance in twin pregnancies: results of the national prospective EsPRIT trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 204 (1): S20. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.10.044.

- ^ Kalafat E, Thilaganathan B, Papageorghiou A, Bhide A, Khalil A (2018). "Significance of placental cord insertion site in twin pregnancys". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 52 (3): 378–384. doi:10.1002/uog.18914. PMID 28976606. S2CID 10906198.

- ^ Sato Y (2006). "Increased Prevalence of Fetal Thrombi in Monochorionic-Twin Placentas. Pediatrics". Pediatrics. 117 (1): e113 – e117. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1501. PMID 16361224. S2CID 19061448.