Sources:

[2]

[3] (in Russian; not online)

[4] (not online)

[5]

[6] (not online)

[7] (not online)

[8] (not online)

[9] (not online)

[10] (may be useful)

[11] (not online)

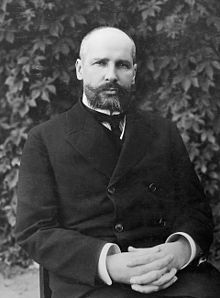

Pyotr Stolypin | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Chairman of Council of Ministers of the Russian Empire | |

| In office 21 July 1906 – 18 September 1911 | |

| Monarch | Nicholas II |

| Preceded by | Ivan Goremykin |

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Kokovtsov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 April 1862 Dresden, Kingdom of Saxony |

| Died | 18 September 1911 (aged 49) Kiev |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Spouse | Olga Borisovna Neidhardt |

Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin (Russian: Пётр Арка́дьевич Столы́пин, IPA: [pʲɵtr ɐˈrkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ stɐˈlɨpʲɪn]; 14 April [O.S. 2 April] 1862 – September 18 [O.S. September 5] 1911) served as Prime Minister and the leader of the third Duma, from 1906 to 1911. His tenure was marked by efforts to counter revolutionary groups and by the implementation of noteworthy agrarian reforms. Stolypin's reforms aimed to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of market-oriented smallholding landowners.[1] He is considered one of the last major statesmen of Imperial Russia with clearly defined public policies and the determination to undertake major reforms.[2]

Family and background

editStolypin was born in Dresden, Saxony, on 14 April 1862. His family was a Russian aristocracy, and Stolypin was related on his father's side to the poet Mikhail Lermontov.[citation needed] His father was Arkady Dmitrievich Stolypin (1821–99), a Russian landowner, descendant of a great noble family, a general in the Russian artillery, and later Commandant of the Kremlin Palace. His mother was Natalia Mikhailovna Stolypina (née Gorchakova; 1827–89), the daughter of the Commanding General of the Russian infantry during the Crimean War and later the Governor General of Warsaw Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov. Stolypin was raised in Srednikovo, a town near Moscow. Later, the family moved into the Kovno province, where he received an education including in English, French and German. He would later write in those languages, though rather unprofessional, but comprehensible.[3]

Stolypin showed similar traits as his father, though he did not smoke, rarely drank alcohol and gambled. He was deeply Russian Orthodox, offen attending churches and masses. As his father, Stolypin possessed a conservative view since his childhood. Journalist A.Z. Izgoev felt that Alexander II's assassination in 1881, provoked by the radical "The People's Will", deeply affected and further contributed to Stolypin's philosophy For Stolypin, the intelligentsia maintained the assassination. The death of his older brother (name?) has not only concerned Stolypin mentally, but the event may have led to his partial paralisis of his right arm, with which he might have fought against his brother's killer. However, according to other accounts, a disease in his early life has contributed to the paralisis. Because of that impairment, Stolypin had to abandon his hobby drawing, and the military career, which had a certain tradition in his family. He also had to control his writing with his left arm.[4]

Stolypin enrolled and studied natural sciences at the Saint Petersburg State University. There, Dmitry Mendeleev once exlaimed "My God, what am I doing? Well, enough. Five, five [the highest grade], splendid" regarding Stolypin's learning performance. Also at the university, he met Olga Borisovna Neidhardt. Although having an affair with his older brother, Olga married Stolypin in 1884. They raised five daughters and a son. Information about their relationship are provided in letters, which were written in Russian with snippets of English and French words and phrases. The first such letter was written on 13 September 1899, which began with "My beloved, il est 10 heures and I want to kiss you before to goo [sic] to bed" and finished with "Je suis satisfait. I kant [sic] live without you, my darling."[5]

After graduating at the university in 1885, Stolypin acted two years at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, then moved to the Statistics Department of the Ministry of Agriculture, likewise working there for two years. There he refreshed his knowledge about agriculture.[6] He returned to Kovno, where he was elected district marshal. People holding that rank, established during the Catherine II era, supervised and administrated an uezd (district), and were concerned with tasks as peasantry affairs, or oversaw local committees, including the Council of Arbiters of the Peace. Although leaving his post, Stolypin still administered on several occasions, so far that one peasant compared his duties with that of a Governor; Stolyping recalled he was only a landowner. Among his achived goals was the establishment of an Agricultural Society, which helped to bring machinery to the peasantry and functioned until the 1940s.

Service at Kovno

edit

Stolypin undertook service in Kovno around the age of 13, from 1889 to 1902. That period was his quietest, according to daughter Maria.

Arriving in Kovno, the young district leader from nobility (уездный предводитель дворянства) fully concentrated on that region. He primarily gave attention to the agricultural society, which controlled and defended local economy. Their main tasks were education of peasants and expansion of farm capacity. It was specifically concerned about implementation of advanced management methods and new cereal crops.[7] During his rule as district ruler, Stolypin became fully acquainted with local indigence and so received administrative experience.[8]

Government in Grodno

editOn 21 June he was appointed Governor of Grodno, becoming the youngest to do so. There he established a Jewish two-years national school, a craftsmanship school and a womens' parish school which beside general subjects also included painting, drawing and crafting.[9][10]

В середине мая 1902 года П. А. Столыпин вывез свою семью с самыми ближайшими домочадцами «на воды» в небольшой немецкий город Эльстер[7]:59. В своих воспоминаниях старшая дочь Мария описывает это время, как одно из самых счастливых в жизни семьи Столыпиных. Она отметила также, что прописанные немецкими врачами грязевые ванны для больной правой руки отца стали давать — к радости всей семьи — положительные результаты[11]:110—113.

Спустя десять дней семейная идиллия неожиданно завершилась. От министра внутренних дел В. К. фон Плеве, сменившего убитого революционерами Д. С. Сипягина, пришла телеграмма с требованием явиться в Петербург[12]. Через три дня причина вызова стала известной — П. А. Столыпин 30 мая 1902 года[13] был неожиданно назначен гродненским губернатором[12]. Инициатива при этом исходила от Плеве, который взял курс на замещение губернаторских должностей местными землевладельцами[12].

21 июня Столыпин прибыл в Гродно и приступил к исполнению обязанностей губернатора. В управлении губернии были некоторые особенности[12]: губернатор был подконтролен генерал-губернатору Вильны (совр. Вильнюс); губернский центр Гродно был меньше двух уездных городов Белостока и Брест-Литовска; национальный состав губернии был неоднороден (в больших городах преобладали евреи; аристократия, в основном, была представлена поляками, а крестьянство — белорусами).

По инициативе Столыпина в Гродно были открыты еврейское двухклассное народное училище, ремесленное училище, а также женское приходское училище особого типа, в котором, кроме общих предметов, преподавались рисование, черчение и рукоделие[12].

На второй день работы он закрыл Польский клуб, где господствовали «повстанческие настроения»[14].

Освоившись в должности губернатора, Столыпин начал проводить реформы, которые включали[12]:

- расселение крестьян на хутора

- ликвидацию чересполосицы

- внедрение искусственных удобрений, улучшенных сельскохозяйственных орудий, многопольных севооборотов, мелиорации

- развитие кооперации

- сельскохозяйственное образование крестьян.

Проводимые нововведения вызывали критику крупных землевладельцев. На одном из заседаний князь Святополк-Четвертинский заявил, что «нам нужна рабочая сила человека, нужен физический труд и способность к нему, а не образование. Образование должно быть доступно обеспеченным классам, но не массе…» Столыпин дал резкую отповедь[12]:

Бояться грамоты и просвещения, бояться света нельзя. Образование народа, правильно и разумно поставленное, никогда не приведёт к анархии…

==

editNext, he became governor of Saratov, where he became known for suppressing peasant unrest in 1905, and gained a reputation as the only governor able to keep a firm hold on his province during this period of widespread revolt. Stolypin was the first governor to use effective police methods against suspected troublemakers and some sources suggest that he had a police record on every adult male in his province.[15] His successes as provincial governor led to Stolypin being appointed interior minister under Ivan Goremykin.

Prime minister

editA few months later, Nicholas II appointed Stolypin to replace Goremykin as Prime Minister. In 1906, Russia was plagued by revolutionary unrest and discontent was widespread among the population. With broad support, leftist organizations waged a violent campaign against the autocracy; throughout Russia, many police officials and bureaucrats were assassinated. To respond to these attacks, Stolypin introduced a new court system that allowed for the arrest and speedy trial of accused offenders. Over three thousand suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906 and 1909. In a Duma session, Kadet party member Feudor Rodichev referred to the gallows as "Stolypin's necktie". As result, Stolypin challenged Rodichev to a duel, but the Kadet party member decided to apologize for the phrase in order to avoid the duel. The expression, however, became a common expression.

Stolypin dissolved the First Duma on July 21 [O.S. July 8] 1906, despite the reluctance of some of its more radical members, in order to facilitate government cooperation.[2] Stolypin introduced land reforms in order to resolve peasant grievances and quell dissent. He also tried to improve the lives of urban laborers and worked towards increasing the power of local governments.

In July 1906, he was elected as Prime Minister. He aimed to create a moderately wealthy class of peasants that would support societal order. (See article "Stolypin's Reform").[16]

On August 25, 1906, Assassins bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his Dacha on Aptekarsky Island. Stolypin was only slightly injured by flying splinters, but 28 others were killed—among them his 15-year-old daughter. Stolypin's three year old son was also seriously wounded.[17]

Stolypin changed the nature of the Duma to attempt to make it more willing to pass legislation proposed by the government.[18][19] After dissolving the Second Duma in June 1907 (Coup of June 1907), he changed the weight of votes more in favor of the nobility and wealthy, reducing the value of lower class votes.[19] This affected the elections to the Third Duma, which returned much more conservative members, more willing to cooperate with the government.[2]

In the spring of 1911, he resigned when one of his bills was defeated. He proposed spreading the system of zemstvo to the southwestern provinces of Russia. It was originally slated to pass with a narrow majority, but Stolypin's political opponents stopped it. Afterwards, he resigned as Prime Minister of the Third Duma.

Assassination

editIn September 1911 Stolypin traveled to Kiev despite police warnings that an assassination plot was afoot. He traveled without bodyguards and refused to wear his bullet-proof vest.

On 1st september 1911 while he was attending a performance of Rimsky-Korsakov's The Tale of Tsar Saltan at the Kiev Opera House in the presence of the Tsar and his two eldest daughters, the Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana, Stolypin was shot twice, once in the arm and once in the chest, by Dmitri Bogrov (born Mordekhai Gershkovich), who was both a Jewish leftist radical and a probable agent of the Okhrana[citation needed]. Stolypin was reported to have coolly risen from his chair, removed his gloves and unbuttoned his jacket, exposing a blood-soaked waistcoat. He sank into his chair and shouted "I am happy to die for the Tsar" before motioning to the Tsar in his imperial box to withdraw to safety. Tsar Nicholas remained in his position and in one last theatrical gesture Stolypin blessed him with a sign of the cross. The next morning the distressed Tsar knelt at Stolypin's hospital bedside and repeated the words "Forgive me". Stolypin died four days later. Bogrov was hanged 10 days after the assassination; the judicial investigation was halted by order of Tsar Nicholas II. This gave rise to suggestions that the assassination was planned not by leftists, but by conservative monarchists who were afraid of Stolypin's reforms and his influence on the Tsar. This, however, has never been proven. Stolypin was buried in the Pechersk Monastery (Lavra) in Kiev, the capital of present-day Ukraine.

Legacy

editOpinions about Stolypin's work are divided. In the unruly atmosphere after the Russian Revolution of 1905 some say that he had to suppress violent revolt and anarchy. However, historians disagree over how realistic Stolypin's policies were. The standard view of most scholars in this field has been that he had little real chance of reforming agriculture since the Russian peasantry was so backward and he had so little time to change things. Others, however, have argued that while it is true that the conservatism of most peasants prevented them from embracing progressive change, Stolypin was correct in thinking that he could "wager on the strong" since there was indeed a layer of strong peasant farmers. This argument is based on evidence drawn from tax returns data, which shows that a significant minority of peasants were paying increasingly higher taxes from the 1890s, a sign that their farming was producing higher profits.

There remains doubt whether, even without the interruption of Stolypin's murder and the First World War, his agricultural policy would have succeeded. The deep conservatism from the mass of peasants made them slow to respond. In 1914 the strip system was still widespread, with only around 10% of the land having been consolidated into farms.[20] Most peasants were unwilling to leave the security of the commune for the uncertainty of individual farming. Furthermore, by 1913, the government's own Ministry of Agriculture had itself begun to lose confidence in the policy.[21]

In a 2008 television poll to select "the greatest Russian", Stolypin placed second, behind Alexander Nevsky and followed by Joseph Stalin.[22]

References

edit- ^ Piotr Arkadevich Stolypin — FactMonster.com at www.factmonster.com

- ^ a b c Imperial Russia, 1815-1917 - Position Paper

- ^ Ascher 2002, pp. 13–4.

- ^ Ascher 2002, pp. 15–6.

- ^ Ascher 2002, pp. 16–7.

- ^ Ascher 2002, p. 18.

- ^ a b Сидоровнин Г. П. (2007). "Глава II. Начало службы. В Западном крае". Пётр Аркадьевич Столыпин: Жизнь за Отечество: Жизнеописание (1862—1911) (in Russian) (3000 ed.). pp. 33–78. ISBN 978-5-9763-0037-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Столыпин П. А. (1991). "Некролог «П. А. Столыпин», опубликованный в газете «Новое время» 6 сентября 1911 г.". In Yuri Felshtinsky (ed.). Нам нужна Великая Россия...: Полное собрание речей в Государственной думе и Государственном совете. 1906—1911. Belfry; Anthology of Russian Publications. Kornello Shatsillo (preface) (100 000 ed.). Young Guard. ISBN 5-235-01576-2. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ V. N. Cherenitsa (1998). "П. А. Столыпин — гродненский губернатор". Orthodox Herald. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Ascher 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Бокwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g Черепица В. Н. (1998), П. А. Столыпин — гродненский губернатор (Православный вестник ed.), archived from the original on 2011-08-11

- ^ Формулярный список о службе Саратовского Губернатора в звании Камергера Двора Его Величества, Действительного Статского Советника Петра Аркадьевича Столыпина. 1906. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|original=ignored (help) - ^ Бородин А. П. (2004). Столыпин: реформы во имя России. Moscow: Вече. p. 19.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|страниц=ignored (help) - ^ ::Peter Stolypin::

- ^ P.A. Stolypin and the Attempts of Reforms

- ^ [1]

- ^ Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy 1891-1924, P225

- ^ a b Oxley, Peter (2001). Russia, 1855 - 1991: from tsars to commissars. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-913418-9.

- ^ Lynch, Michael From Autocracy to Communism: Russia 1894-1941 p.42 ISBN 978-0-340-96590-0

- ^ Lynch, Michael From Autocracy to Communism: Russia 1894-1941 p.42 ISBN 978-0-340-96590-0

- ^ Stalin voted third-best Russian

Further reading

edit- Ascher, Abraham (2001). P. A. Stolypin: The Search for Stability in Late Imperial Russia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3977-3.

- McDonald, David MacLaren (1992). United Government and Foreign Policy in Russia, 1900-1914. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674922396.

- Conroy, M.S. (1976), Peter Arkadʹevich Stolypin: Practical Politics in Late Tsarist Russia, Westview Press, (Boulder), 1976. ISBN 0-8915-8143-X