Origins

edit

The Arabs are a Semitic people who speak Arabic, which is a Semitic language that belongs to the Afroasiatic language family. The majority of scholars accept the "Arabian peninsula" has long been accepted as the original Urheimat (linguistic homeland) of the Semitic languages.[1][2][3][4] Or to be from the Levant.[5] The ancient Semitic peoples lived in the ancient Near East, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian Peninsula from the 3rd millennium BC to the end of antiquity. Proto-Semitic likely reached the Arabian Peninsula by the 4th millennium BC, and its daughter languages spread outward from there,[6] while Old Arabic began to differentiate from Central Semitic by the start of the 1st millennium BCE.[7] Central Semitic is a branch of the Semitic language includes Arabic, Aramaic, Canaanite, Phoenician, Hebrew and others.[8][9] The origins of Proto-Semitic may lie in the Arabian Peninsula, with the language spreading from there to other regions. This theory proposes that Semitic peoples reached Mesopotamia and other areas from the deserts to the west, such as the Akkadians who entered Mesopotamia around the late 4th millennium BC.[6] The origins of Semitic peoples are thought to include various regions Mesopotamia, the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa. Some view that Semitic may have originated in the Levant around 3800 BC and subsequently spread to the Horn of Africa around 800 BC from Arabia, as well as to North Africa.[10][11][12]

According to Arab-Islamic-Jewish traditions, Ishmael son of Abraham was "father of the Arabs", to be the ancestor of the Arabs.[13][14][15][16][17] That Abraham be the ancestor of the Arabs and Israelites.[18][19] Shem's descendants: Genesis chapter 10 verses 21–30 gives one list of descendants of Shem. In chapter 11 verses 10–26 a second list of descendants of Shem names Abraham and thus the Arabs and Israelites.[20] Genetic research has indicated that Arabs and Jews share common genetic ancestry and are closely related along with other Semitic peoples.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28] Additionally, it is common for Arabs and Jews to refer to each other as "cousins".[29][30][31][32][33] The Book of Genesis narrates that God promised Hagar to beget from Ishmael twelve princes and turn him to a "great nation".[34][35][36][37][38][39] Ya'rub is the grandson of Abir being the son of Qahtan/Joktan is an ancestor of the Ishmaelites and the Israelites according to the "Table of Nations" in the Book of Genesis (Genesis 10–11) and the Books of Chronicles (1 Chronicles 1). Qahtan/Joktan mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, he descends from Shem, son of Noah. Joktan's sons in the order provided in Genesis 10:26–29, were Almodad, Sheleph, Hazarmaveth, Jerah, Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah, Obal, Abimael, Sheba, Ophir, Havilah, and Jobab.[40] Keturah was a wife of Abraham, according to the Book of Genesis, Abraham married Keturah after the death of his first wife, Sarah. Abraham and Keturah had six sons: Zimran, Jokshan, Medan, Midian, Ishbak, and Shuah. Genesis and First Chronicles also list seven of her grandsons (Sheba, Dedan, Ephah, Epher, Hanoch, Abida, and Eldaah).[41][42][41] Keturah's sons were to have represented the Arab tribes who lived south and east of Palestine (Genesis 25:1–6).[43]

Ishmael was considered the ancestor of Muhammad the founder of Islam, was linked to him through the lineage of the patriarch Adnan. Ishmael also have been the ancestor of the Southern Arabs through his descendant Qahtan.[44] "Zayd ibn Amr" was another Pre-Islamic figure who refused idolatry and preached monotheism, claiming it was the original belief of their [Arabs] father Ishmael.[45] The tribes of Central West Arabia called themselves the "people of Abraham and the offspring of Ishmael."[46] Ibn Khaldun an Arab scholar in the 8th century described the Arabs were divided into two groups: ‘Adnan and Qahtan, both of which were attributed to Ishmaelite origins. He provided a definition of who the Arabs were, stating that they were a large nation occupying territories from the Atlantic Ocean (Maghreb) in the West (Mashriq) to Yemen and the Indian border in the East. According to him, most Arabs descending from the Qudā‘a, Qahtan, and ‘Adnan tribes (Ishmaelite).[47]

The Hebrew Bible occasionally refers to Aravi peoples (or variants thereof), translated as "Arab". The scope of the term at that early stage is unclear, but it seems to have referred to various desert-dwelling Semitic tribes in the Levant and Arabia. And the Book of Jubilees claims that the sons of Ishmael intermingled with the 6 sons of Keturah, from Abraham, and their descendants were called Arabs and Ishmaelites: "And Ishmael and his sons, and the sons of Keturah and their sons, went together and dwelt from Paran to the entering in of Babylon in all the land towards the East facing the desert. And these mingled with each other, and their name was called Arabs, and Ishmaelites".[48][49][50][51][52]

The Biblical texts mention Ishmael, son of Abraham, as the ancestor of twelve nomadic tribes who settled in the desert lands between North Arabia, Egypt, and Palestine (Genesis 25:13-16).[53] The Ishmaelites denoted a broad confederation of people, including sub-groups such as the Midianites, Amalekites, and Hagarites (Genesis 37:25, 27; 39:1).[54][55][56] Chapter 25 lists his sons as: And these are the names of the sons of Ishmael, by their names, according to their generations: the firstborn of Ishmael Nebaioth; and Kedar, and Adbeel, and Mibsam, And Mishma, and Dumah, and Massa, Hadar, and Tema, Jetur, Naphish, and Kedemah.[57] The Bible also mentions "Arabs" or "Arabians" as nomads wandering in North Arabia and Southern Palestine, with some verses associating them with animal-breeding, such as the tribute of flocks, rams, and goats brought to Jehoshaphat by the Arabs.[58][59][60][61][62][63]

The Quran mention, Ibrahim (Abraham) and his wife Hajar (Hagar) bore a prophetic child named Ishmael, who was gifted by God all of Ishmael, Alyasa, Yunus and Lut a favor above the nations.[64] God ordered Ibrahim to bring Hajar and Ishmael to Mecca, where he prayed for them to be provided with water and fruits. Hajar ran between the hills of Safa and Marwa in search of water, and an angel appeared to them and provided them with water. Ishmael grew up in Mecca. Ibrahim was later ordered to sacrifice Ishmael in a dream, but God intervened and replaced him with a goat. Ibrahim and Ishmael then built the Kaaba in Mecca, which was originally constructed by Adam.[65] The Quran calls itself ʿarabiy, "Arabic", and Mubin, "clear". Quran 43:2-3

According to the Samaritan book Asaṭīr adds:[66]: 262 "And after the death of Abraham, Ishmael reigned twenty-seven years; And all the children of Nebaot ruled for one year in the lifetime of Ishmael; And for thirty years after his death from the river of Egypt to the river Euphrates; and they built Mecca."[67] Josephus also lists the sons and states that they "...inhabit the lands which are between Euphrates and the Red Sea, the name of which country is Nabathæa.[68][69] The Targum Onkelos annotates (Genesis 25:16), describing the extent of their settlements: The Ishmaelites lived from Hindekaia (India) to Chalutsa (possibly in Arabia), by the side of Mizraim (Egypt), and from the area around Arthur (Assyria) up towards the north. This description suggests that the Ishmaelites were a widely dispersed group with a presence across a significant portion of the ancient Near East.[70][71]

History

editThe nomads of Arabia have been spreading through the desert fringes of the Fertile Crescent since at least 3000 BC, but the first known reference to the Arabs as a distinct group is from an Assyrian scribe recording a battle in 853 BC.[72][73] The history of the Arabs during the pre-Islamic period in various regions, including Arabia, Levant, Mesopotamia, and Egypt. The Arabs were mentioned by their neighbors, such as Assyrian and Babylonian Royal Inscriptions from 9th to 6th century BCE, mention the king of Qedar as king of the Arabs and King of the Ishmaelites.[74][75][76][77] Of the names of the sons of Ishmael the names "Nabat, Kedar, Abdeel, Dumah, Massa, and Teman" were mentioned in the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions as tribes of the Ishmaelites. Jesur was mentioned in Greek inscriptions in the 1st century BCE.[78] There are also records from Sargon's reign that mention sellers of iron to people called Arabs in Ḫuzaza in Babylon, causing Sargon to prohibit such trade out of fear that the Arabs might use the resource to manufacture weapons against the Assyrian army. The history of the Arabs in relation to the Bible shows that they were a significant part of the region and played a role in the lives of the Israelites. The study asserts that the Arab nation is an ancient and significant entity; however, it highlights that the Arabs lacked a collective awareness of their unity. They did not inscribe their identity as Arabs or assert exclusive ownership over specific territories.[79]

Magan, Midian, and ʿĀd are all ancient tribes or civilizations that are mentioned in Arabic literature and have roots in the Arabia. Magan (Arabic: مِجَانُ, Majan), known for its production of copper and other metals, the region was an important trading center in ancient times and is mentioned in the Qur'an as a place where the prophet Moses traveled during his lifetime.[81][82] Midian (Arabic: مَدْيَن, Madyan), on the other hand, was a region located in the northwestern part of the Arabia, the people of Midian are mentioned in the Qur'an as having worshiped idols and having been punished by God for their disobedience.[83][84] The prophet Moses also lived in Midian for a time, where he married and worked as a shepherd. ʿĀd (Arabic: عَادَ, ʿĀd), as mentioned earlier, was an ancient tribe that lived in the southern Arabia, the tribe was known for its wealth, power, and advanced technology, but they were ultimately destroyed by a powerful windstorm as punishment for their disobedience to God.[85] ʿĀd is regarded as one of the original Arab tribes.[86][87]

The historian Herodotus provided extensive information about Arabia, describing the spices, terrain, folklore, trade, clothing, and weapons of the Arabs. In his third book, he mentioned the Arabs (Άραβες) as a force to be reckoned with in the north of the Arabian Peninsula just before Cambyses’ campaign against Egypt. Other Greek and Latin authors who wrote about Arabia include Theophrastus, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Pliny the Elder. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus wrote about the Arabs and their king, mentioning their relationship with Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt. The tribute paid by the Arab king to Cleopatra was collected by Herod, the king of the Jews, but the Arab king later became slow in his payments and refused to pay without further deductions. This sheds some light on the relations between the Arabs, Jews, and Egypt at that time.[88] Geshem the Arab was an Arab man who opposed Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible (Neh. 2:19, 6:1). He was likely the chief of the Arab tribe "Gushamu" and have been a powerful ruler with influence stretching from northern Arabia to Judah. The Arabs and the Samaritans made efforts to hinder Nehemiah's rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem.[89][90][91]

The term "Saracens" was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the "Arabs" who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Petraea (Levant) and Arabia Deserta (Arabia).[92][93] The Christians of Iberia used the term Moor to describe all the Arabs and Muslims of that time. Arabs of Medina referred to the nomadic tribes of the deserts as the A'raab, and considered themselves sedentary, but were aware of their close racial bonds. Hagarenes is a term widely used by early Syriac, Greek, and Armenian to describe the early Arab conquerors of Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt, refers to the descendants of Hagar, who bore a son named Ishmael to Abraham in the Old Testament. In the Bible, the Hagarenes referred to as "Ishmaelites" or "Arabs.".[94] The Arab conquests in the 7th century was a sudden and dramatic conquest led by Arab armies, which quickly conquered much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. It was a significant moment for Islam, which saw itself as the successor of Judaism and Christianity.[95] The term ʾiʿrāb has the same root refers to the Bedouin tribes of the desert who rejected Islam and resisted Muhammad.(Quran 9:97) The 14th century Kebra Nagast says "And therefore the children of Ishmael became kings over Tereb, and over Kebet, and over Nôbâ, and Sôba, and Kuergue, and Kîfî, and Mâkâ, and Môrnâ, and Fînḳânâ, and ’Arsîbânâ, and Lîbâ, and Mase'a, for they were the seed of Shem."[96]

Antiquity

editLimited local historical coverage of these civilizations means that archaeological evidence, foreign accounts and Arab oral traditions are largely relied on to reconstruct this period. Prominent civilizations at the time included, Dilmun civilization was an important trading centre[99] which at the height of its power controlled the Arabian Gulf trading routes.[99] The Sumerians regarded Dilmun as holy land.[100] Dilmun is regarded as one of the oldest ancient civilizations in the Middle East.[101][102] which arose around the 4th millennium BCE and lasted to 538 BCE. Gerrha was an ancient city of Eastern Arabia, on the west side of the Gulf, Gerrha was the center of an Arab kingdom from approximately 650 BC to circa AD 300. Thamud, which arose around the 1st millennium BCE and lasted to about 300 CE. From the beginning of the first millennium BCE, Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, texts give a clearer picture of the Arabs' emergence. The earliest are written in variants of epigraphic south Arabian musnad script, including the 8th century BCE Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, the Thamudic texts found throughout the Arabian Peninsula and Sinai.

The Qedarites were a largely nomadic ancient Arab tribal confederation centred in the Wādī Sirḥān in the Syrian Desert. They were known for their nomadic lifestyle and for their role in the caravan trade that linked the Arabian Peninsula with the Mediterranean world. The Qedarites gradually expanded their territory over the course of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, and by the 6th century BC, they had consolidated into a kingdom that covered a large area in northern Arabia, southern Palestine, and the Sinai Peninsula. The Qedarites were influential in the ancient Near East, and their kingdom played a significant role in the political and economic affairs of the region for several centuries.[103]

Sheba (Arabic: سَبَأٌ Saba) is kingdom mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Quran. Sheba features in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian traditions, whose lineage goes back to Qahtan son of Hud, one of the ancestors of the Arabs,[104][105][106] Sheba was mentioned in Assyrian inscriptions and in the writings of Greek and Roman writers.[107] One of the ancient written references that also spoke of Sheba is the Old Testament, which stated that the people of Sheba supplied Syria and Egypt with incense, especially frankincense, and exported gold and precious stones to them.[108] The Queen of Sheba who travelled to Jerusalem to question King Solomon, great caravan of camels, carrying gifts of gold, precious stones, and spices,[109] when she arrived, she was impressed by the wisdom and wealth of King Solomon, and she posed a series of difficult questions to him.[110] King Solomon was able to answer all of her questions, and the Queen of Sheba was impressed by his wisdom and his wealth.(1 Kings 10)

Sabaeans are mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. In the Quran,[111] they are described as either Sabaʾ (سَبَأ, not to be confused with Ṣābiʾ, صَابِئ),[105][106] or as Qawm Tubbaʿ (Arabic: قَوْم تُبَّع, lit. 'People of Tubbaʿ').[112][113] They were known for their prosperous trade and agricultural economy, which was based on the cultivation of frankincense and myrrh, these highly valued aromatic resins were exported to Egypt, Greece, and Rome, making the Sabaeans wealthy and powerful, they also traded in spices, textiles, and other luxury goods. The Maʾrib Dam was one of the greatest engineering achievements of the ancient world, and it provided water for the city of Maʾrib and the surrounding agricultural lands.[114][115][107]

Lihyan also called Dadān or Dedan was a powerful and highly organized ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language.[116] The Lihyanites were known for their advanced organization and governance, and they played a significant role in the cultural and economic life of the region. The kingdom was centered around the city of Dedan (modern-day Al Ula), and it controlled a large territory that extended from Yathrib in the south to parts of the Levant in the north.[117][118][119] The Arab genealogies consider the Banu Lihyan to be Ishmaelites, and used Dadanitic language.[120]

The Kingdom of Ma'in was an ancient Arab kingdom with a hereditary monarchy system and a focus on agriculture and trade.[121] Proposed dates range from the 15th century BC to the 1st century AD Its history has been recorded through inscriptions and classical Greek and Roman books, although the exact start and end dates of the kingdom are still debated. The Ma'in people had a local governance system with councils called "Mazood," and each city had its own temple that housed one or more gods. They also adopted the Phoenician alphabet and used it to write their language. The kingdom eventually fell to the Arab Sabaean people.[122][123]

Qataban was an ancient kingdom located in the South Arabia, which existed from the early 1st millennium BCE till the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.[125][125][126] It developed into a centralized state in the 6th century BC with two co-kings ruling poles.[125][127] Qataban expanded its territory, including the conquest of Ma'in and successful campaigns against the Sabaeans.[126][124][128] It challenged the supremacy of the Sabaeans in the region and waged a successful war against Hadramawt in the 3rd century BCE.[124][129] Qataban's power declined in the following centuries, leading to its annexation by Hadramawt and Ḥimyar in the 1st century CE.[130][126][124][125][131][124]

The Kingdom of Hadhramaut it was known for its rich cultural heritage, as well as its strategic location along important trade routes that connected the Middle East, South Asia, and East Africa.[132][133] The Kingdom was established around the 3rd century BC, and it reached its peak during the 2nd century AD, when it controlled much of the southern Arabian Peninsula. The kingdom was known for its impressive architecture, particularly its distinctive towers, which were used as watchtowers, defensive structures, and homes for wealthy families.[134] The people of Hadhramaut were skilled in agriculture, especially in growing frankincense and myrrh. They had a strong maritime culture and traded with India, East Africa, and Southeast Asia.[135] Although the kingdom declined in the 4th century, Hadhramaut remained a cultural and economic center. Its legacy can still be seen today.[136]

The ancient Kingdom of Awsān (8th century BC–7th century BC) was indeed one of the most important small kingdoms of South Arabia, and its capital Ḥajar Yaḥirr was a significant center of trade and commerce in the ancient world. It is fascinating to learn about the rich history of this region and the cultural heritage that has been preserved through the archaeological sites like Ḥajar Asfal. The destruction of the city in the 7th century BCE by the king and Mukarrib of Saba' Karab El Watar is a significant event in the history of South Arabia. It highlights the complex political and social dynamics that characterized the region at the time and the power struggles between different kingdoms and rulers. The victory of the Sabaeans over Awsān is also a testament to the military might and strategic prowess of the Sabaeans, who were one of the most powerful and influential kingdoms in the region.[137]

The Himyarite Kingdom or Himyar, was an ancient kingdom that existed from around the 2nd century BCE to the 6th century CE. It was centered in the city of Zafar, which is located in present-day Yemen. The Himyarites were a Arab people who spoke a South Arabian language and were known for their prowess in trade and seafaring,[138] they controlled the southern part of Arabia and had a prosperous economy based on agriculture, commerce, and maritime trade, they were skilled in irrigation and terracing, which allowed them to cultivate crops in the arid environment. The Himyarites converted to Judaism in the 4th century CE, and their rulers became known as the "Kings of the Jews", this conversion was likely influenced by their trade connections with the Jewish communities of the Red Sea region and the Levant, however, the Himyarites also tolerated other religions, including Christianity and the local pagan religions.[139][140]

Classical antiquity

editThe Nabataeans were nomadic Arabs who moved into territory vacated by the Edomites– Semites who settled the region centuries before them.[141][142] Their early inscriptions were in Aramaic, but gradually switched to Arabic, and since they had writing, it was they who made the first inscriptions in Arabic. The Nabataean alphabet was adopted by Arabs to the south, and evolved into modern Arabic script around the 4th century. This is attested by Safaitic inscriptions (beginning in the 1st century BCE) and the many Arabic personal names in Nabataean inscriptions. From about the 2nd century BCE, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw reveal a dialect no longer considered proto-Arabic, but pre-classical Arabic. Five Syriac inscriptions mentioning Arabs have been found at Sumatar Harabesi, one of which dates to the 2nd century CE.[143][144]

Arabs are first recorded in Palmyra in the late first millennium BC.[145] The soldiers of the sheikh Zabdibel, who aided the Seleucids in the battle of Raphia (217 BCE), were described as Arabs; Zabdibel and his men were not actually identified as Palmyrenes in the texts, but the name "Zabdibel" is a Palmyrene name leading to the conclusion that the sheikh hailed from Palmyra.[146] After the Battle of Edessa in 260 CE. Valerian's capture by the Sassanian king Shapur I was a significant blow to Rome, and it left the empire vulnerable to further attacks. Zenobia was able to capture most of the Near East, including Egypt and parts of Asia Minor. However, their empire was short-lived, as Aurelian was able to defeat the Palmyrenes and recover the lost territories. The Palmyrenes were helped by their Arab allies, but Aurelian was also able to leverage his own alliances to defeat Zenobia and her army. Ultimately, the Palmyrene Empire lasted only a few years, but it had a significant impact on the history of the Roman Empire and the Near East.

The Itureans were an Arab people who inhabited the region of Iturea,[147][148][149][150] emerged as a prominent power in the region after the decline of the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd century BCE, from their base around Mount Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley, they came to dominate vast stretches of Syrian territory,[151] and appear to have penetrated into northern parts of Palestine as far as the Galilee.[152] Tanukhids were an Arab tribal confederation that lived in the central and eastern Arabian Peninsula during the late ancient and early medieval periods. As mentioned earlier, they were a branch of the Rabi'ah tribe, which was one of the largest Arab tribes in the pre-Islamic period. They were known for their military prowess and played a significant role in the early Islamic period, fighting in battles against the Byzantine and Sassanian empires and contributing to the expansion of the Arab empire.[153]

The Osroene Arabs, also known as the Abgarids,[154][155][156] were in possession of the city of Edessa in the ancient Near East for a significant period of time. Edessa was located in the region of Osroene, which was an ancient kingdom that existed from the 2nd century BC to the 3rd century CE. They established a dynasty known as the Abgarids, which ruled Edessa for several centuries. The most famous ruler of the dynasty was Abgar V, who is said to have corresponded with Jesus Christ and is believed to have converted to Christianity.[157] The Abgarids played an important role in the early history of Christianity in the region, and Edessa became a center of Christian learning and scholarship.[158] The Kingdom of Hatra was an ancient city located in the region of Mesopotamia, it was founded in the 2nd or 3rd century BCE and flourished as a major center of trade and culture during the Parthian Empire. The rulers of Hatra were known as the Arsacid dynasty, which was a branch of the Parthian ruling family. However, in the 2nd century CE, the Arab tribe of Banu Tanukh seized control of Hatra and established their own dynasty. The Arab rulers of Hatra assumed the title of "malka," which means king in Arabic, and they often referred to themselves as the "King of the Arabs."[159]

The Osroeni and Hatrans were part of several Arab groups or communities in upper Mesopotamia, who also included the Praetavi of Singara reported by Pliny the Elder, and the Arabs of Adiabene which was an ancient kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, its chief city was Arbela (Arba-ilu), where Mar Uqba had a school, or the neighboring Hazzah, by which name the later Arabs also called Arbela.[160][161] This elaborate Arab presence in upper Mesopotamia was acknowledged by the Sasanians, who called the region Arbayistan, meaning "land of the Arabs", is first attested as a province in the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht inscription of the second Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) Shapur I (r. 240–270),[162] which was erected in c. 262.[163][164] The Emesene were a dynasty of Arab priest-kings that ruled the city of Emesa (modern-day Homs, Syria) in the Roman province of Syria from the 1st century CE to the 3rd century CE. The dynasty is notable for producing a number of high priests of the god El-Gabal, who were also influential in Roman politics and culture. The first ruler of the Emesene dynasty was Sampsiceramus I, who came to power in 64 CE. He was succeeded by his son, Iamblichus, who was followed by his own son, Sampsiceramus II. Under Sampsiceramus II, Emesa became a client kingdom of the Roman Empire, and the dynasty became more closely tied to Roman political and cultural traditions.[165]

Late antiquity

editThe Ghassanids, Lakhmids and Kindites were the last major migration of pre-Islamic Arabs out of Yemen to the north. The Ghassanids increased the Semitic presence in then-Hellenized Syria, the majority of Semites were Aramaic peoples. They mainly settled in the Hauran region and spread to modern Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan. Greeks and Romans referred to all the nomadic population of the desert in the Near East as Arabi. The Romans called Yemen "Arabia Felix".[166] The Romans called the vassal nomadic states within the Roman Empire Arabia Petraea, after the city of Petra, and called unconquered deserts bordering the empire to the south and east Arabia Magna.

The Lakhmids as a dynasty inherited their power from the Tanukhids, the mid Tigris region around their capital Al-Hira. They ended up allying with the Sassanids against the Ghassanids and the Byzantine Empire. The Lakhmids contested control of the Central Arabian tribes with the Kindites with the Lakhmids eventually destroying the Kingdom of Kinda in 540 after the fall of their main ally Himyar. The Persian Sassanids dissolved the Lakhmid dynasty in 602, being under puppet kings, then under their direct control.[167] The Kindites migrated from Yemen along with the Ghassanids and Lakhmids, but were turned back in Bahrain by the Abdul Qais Rabi'a tribe. They returned to Yemen and allied themselves with the Himyarites who installed them as a vassal kingdom that ruled Central Arabia from "Qaryah Dhat Kahl" (the present-day called Qaryat al-Faw). They ruled much of the Northern/Central Arabian peninsula, until they were destroyed by the Lakhmid king Al-Mundhir, and his son 'Amr.

The Ghassanids were an Arab tribe in the Levant in the early third century. According to Arab genealogical tradition, they were considered a branch of the Azd tribe. They fought alongside the Byzantines against the Sasanians and Arab Lakhmids. Most Ghassanids were Christians, converting to Christianity in the first few centuries, and some merged with Hellenized Christian communities. After the Muslim conquest of the Levant, few Ghassanids became Muslims, and most remained Christian and joined Melkite and Syriac communities within what is now Jordan, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.[168] The Salihids were Arab foederati in the 5th century, were ardent Christians, and their period is less documented than the preceding and succeeding periods due to a scarcity of sources. Most references to the Salihids in Arabic sources derive from the work of Hisham ibn al-Kalbi, with the Tarikh of Ya'qubi considered valuable for determining the Salihids' fall and the terms of their foedus with the Byzantines.[169]

Middle Ages

editDuring the Middle Ages, Arab civilization flourished and the Arabs made significant contributions to the fields of science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, and literature, with the rise of great cities like Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordoba, they became centers of learning, attracting scholars, scientists, and intellectuals.[170][171] Arabs forged many empires and dynasties, most notably, the Rashidun Empire, the Umayyad Empire, the Abbasid Empire, the Fatimid Empire, among others. These empires were characterized by their expansion, scientific achievements, and cultural flourishing, extended from Spain to India[170] The Arabs during the Middle Ages was a vibrant and dynamic region that left a lasting impact on the world.[171]

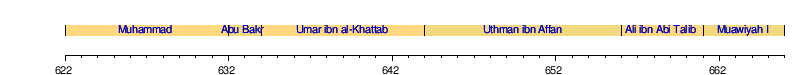

The rise of Islam began when Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to Medina in an event known as the Hijra. Muhammad spent the last ten years of his life engaged in a series of battles to establish and expand the Muslim community. From 622 to 632, he led the Muslims in a state of war against the Meccans.[172] During this period, the Arabs conquered the region of Basra, and under the leadership of Umar, they established a base and built a mosque there. Another conquest was Midian, but due to its harsh environment, the settlers eventually moved to Kufa. Umar successfully defeated rebellions by various Arab tribes, bringing stability to the entire Arabian peninsula and unifying it. Under the leadership of Uthman, the Arab empire expanded through the conquest of Persia, with the capture of Fars in 650 and parts of Khorasan in 651.[173] The conquest of Armenia also began in the 640s. During this time, the Rashidun Empire extended its rule over the entire Sassanid Empire and more than two-thirds of the Eastern Roman Empire. However, the reign of Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth caliph, was marred by the First Fitna, or the First Islamic Civil War, which lasted throughout his rule. After a peace treaty with Hassan ibn Ali and the suppression of early Kharijite disturbances, Muawiyah I became the Caliph.[174] This marked a significant transition in leadership.[173][175]

Arab empires

editRashidun era (632–661)

editAfter the death of Muhammad in 632, Rashidun armies launched campaigns of conquest, establishing the Caliphate, or Islamic Empire, one of the largest empires in history. It was larger and lasted longer than the previous Arab empire Tanukhids of Queen Mawia or the Arab Palmyrene Empire. The Rashidun state was a completely new state and unlike the Arab kingdoms of its century such as the Himyarite, Lakhmids or Ghassanids.

During the Rashidun era, the Arab community expanded rapidly, conquering many territories and establishing a vast Arab empire, which is marked by the reign of the first four caliphs, or leaders, of the Arab community.[176] These caliphs are Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali, who are collectively known as the Rashidun, meaning "rightly guided." The Rashidun era is significant in Arab and Islamic history as it marks the beginning of the Arab empire and the spread of Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula. During this time, the Arab community faced numerous challenges, including internal divisions and external threats from neighboring empires.[176][177]

Under the leadership of Abu Bakr, the Arab community successfully quelled a rebellion by some tribes who refused to pay Zakat, or Islamic charity. During the reign of Umar ibn al-Khattab, the Arab empire expanded significantly, conquering territories such as Egypt, Syria, and Iraq. The reign of Uthman ibn Affan was marked by internal dissent and rebellion, which ultimately led to his assassination. Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, succeeded Uthman as caliph but faced opposition from some members of the Islamic community who believed he was not rightfully appointed.[176] Despite these challenges, the Rashidun era is remembered as a time of great progress and achievement in Arab and Islamic history, the caliphs established a system of governance that emphasized justice and equality for all members of the Islamic community. They also oversaw the compilation of the Quran into a single text and spread Arabic teachings and principles throughout the empire. Overall, the Rashidun era played a crucial role in shaping Arab history and continues to be revered by Muslims worldwide as a period of exemplary leadership and guidance.[178]

Umayyad era (661–750 & 756–1031)

editIn 661, the Rashidun Caliphate fell into the hands of the Umayyad dynasty and Damascus was established as the empire's capital. The Umayyads were proud of their Arab identity and sponsored the poetry and culture of pre-Islamic Arabia. They established garrison towns at Ramla, Raqqa, Basra, Kufa, Mosul and Samarra, all of which developed into major cities.[179] Caliph Abd al-Malik established Arabic as the Caliphate's official language in 686.[180] Caliph Umar II strove to resolve the conflict when he came to power in 717. He rectified the disparity, demanding that all Muslims be treated as equals, but his intended reforms did not take effect, as he died after only three years of rule. By now, discontent with the Umayyads swept the region and an uprising occurred in which the Abbasids came to power and moved the capital to Baghdad.

Umayyads expanded their Empire westwards capturing North Africa from the Byzantines. Before the Arab conquest, North Africa was conquered or settled by various people including Punics, Vandals and Romans. After the Abbasid Revolution, the Umayyads lost most of their territories with the exception of Iberia.

Their last holding became known as the Emirate of Córdoba. It wasn't until the rule of the grandson of the founder of this new emirate that the state entered a new phase as the Caliphate of Córdoba. This new state was characterized by an expansion of trade, culture and knowledge, and saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture and the library of Al-Ḥakam II which housed over 400,000 volumes. With the collapse of the Umayyad state in 1031 CE, Islamic Spain was divided into small kingdoms.[181]

Abbasid era (750–1258 & 1261–1517)

editThe Abbasids were the descendants of Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, one of the youngest uncles of Muhammad and of the same Banu Hashim clan. The Abbasids led a revolt against the Umayyads and defeated them in the Battle of the Zab effectively ending their rule in all parts of the Empire with the exception of al-Andalus. In 762, the second Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur founded the city of Baghdad and declared it the capital of the Caliphate. Unlike the Umayyads, the Abbasids had the support of non-Arab subjects.[179] The Islamic Golden Age was inaugurated by the middle of the 8th century by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to the newly founded city of Baghdad. The Abbasids were influenced by the Quranic injunctions and hadith such as "The ink of the scholar is more holy than the blood of martyrs" stressing the value of knowledge.

During this period the Arab Empire became an intellectual centre for science, philosophy, medicine and education as the Abbasids championed the cause of knowledge and established the "House of Wisdom" (Arabic: بيت الحكمة) in Baghdad. Rival dynasties such as the Fatimids of Egypt and the Umayyads of al-Andalus were also major intellectual centres with cities such as Cairo and Córdoba rivaling Baghdad.[182] The Abbasids ruled for 200 years before they lost their central control when Wilayas began to fracture in the 10th century; afterwards, in the 1190s, there was a revival of their power, which was ended by the Mongols, who conquered Baghdad in 1258 and killed the Caliph Al-Musta'sim. Members of the Abbasid royal family escaped the massacre and resorted to Cairo, which had broken from the Abbasid rule two years earlier; the Mamluk generals taking the political side of the kingdom while Abbasid Caliphs were engaged in civil activities and continued patronizing science, arts and literature.

Fatimid era (909–1171)

editThe Fatimid caliphate was founded by al-Mahdi Billah, a descendant of Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad, the Fatimid Caliphate was a Shia that existed from 909 to 1171 CE. The empire was based in North Africa, with its capital in Cairo, and at its height, it controlled a vast territory that included parts of modern-day Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Syria, and Palestine. The Fatimid state took shape among the Kutama, in the West of the North African littoral, in Algeria, in 909 conquering Raqqada, the Aghlabid capital. In 921 the Fatimids established the Tunisian city of Mahdia as their new capital. In 948 they shifted their capital to Al-Mansuriya, near Kairouan in Tunisia, and in 969 they conquered Egypt and established Cairo as the capital of their caliphate.

The Fatimids were known for their religious tolerance and intellectual achievements, they established a network of universities and libraries that became centers of learning in the Islamic world. They also promoted the arts, architecture, and literature, which flourished under their patronage. One of the most notable achievements of the Fatimids was the construction of the Al-Azhar Mosque and Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Founded in 970 CE, it is one of the oldest universities in the world and remains an important center of Islamic learning to this day. The Fatimids also had a significant impact on the development of Islamic theology and jurisprudence. They were known for their support of Shia Islam and their promotion of the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam. Despite their many achievements, the Fatimids faced numerous challenges during their reign. They were constantly at war with neighboring empires, including the Abbasid Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire. They also faced internal conflicts and rebellions, which weakened their empire over time. In 1171 CE, the Fatimid Caliphate was conquered by the Ayyubid dynasty, led by Saladin. Although the Fatimid dynasty came to an end, its legacy continued to influence Arab-Islamic culture and society for centuries to come.[183]

Ottoman era (1517–1918)

editFrom 1517 to 1918, The Ottomans defeated the Mamluk Sultanate in Cairo, and ended the Abbasid Caliphate in the battles of Marj Dabiq and Ridaniya. They entered the Levant and Egypt as conquerors, and brought down the Abbasid caliphate after it lasted for many centuries. In 1911, Arab intellectuals and politicians from throughout the Levant formed al-Fatat ("the Young Arab Society"), a small Arab nationalist club, in Paris. Its stated aim was "raising the level of the Arab nation to the level of modern nations." In the first few years of its existence, al-Fatat called for greater autonomy within a unified Ottoman state rather than Arab independence from the empire. Al-Fatat hosted the Arab Congress of 1913 in Paris, the purpose of which was to discuss desired reforms with other dissenting individuals from the Arab world.[184] However, as the Ottoman authorities cracked down on the organization's activities and members, al-Fatat went underground and demanded the complete independence and unity of the Arab provinces.[185]

The Arab Revolt was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, began in 1916, led by Sherif Hussein bin Ali, the goal of the revolt was to gain independence for the Arab lands under Ottoman rule and to create a unified Arab state. The revolt was sparked by a number of factors, including the Arab desire for greater autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, resentment towards Ottoman policies, and the influence of Arab nationalist movements. The Arab Revolt was a significant factor in the eventual defeat of the Ottoman Empire. The revolt helped to weaken Ottoman military power and tie up Ottoman forces that could have been deployed elsewhere. It also helped to increase support for Arab independence and nationalism, which would have a lasting impact on the region in the years to come.[186][187] The Empire's defeat and the occupation of part of its territory by the Allied Powers in the aftermath of World War I, the Sykes–Picot Agreement had a significant impact on the Arab world and its people. The agreement divided the Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire into zones of control for France and Britain, ignoring the aspirations of the Arab people for independence and self-determination.[188]

Renaissance

editThe Golden Age of Arab Civilization known as the "Islamic Golden Age", traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.[189][190][191] The period is traditionally said to have ended with the collapse of the Abbasid caliphate due to Siege of Baghdad in 1258.[192] During this time, Arab scholars made significant contributions to fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy. These advancements had a profound impact on European scholars during the Renaissance.[193]

The Arabs shared its knowledge and ideas with Europe, including translations of Arabic texts.[194] These translations had a significant impact on culture of Europe, leading to the transformation of many philosophical disciplines in the medieval Latin world. Additionally, the Arabs made original innovations in various fields, including the arts, agriculture, alchemy, music, and pottery, and traditional star names such as Aldebaran, scientific terms like alchemy (whence also chemistry), algebra, algorithm, etc. and names of commodities such as sugar, camphor, cotton, coffee, etc.[195][196][197][198]

From the medieval scholars of the Renaissance of the 12th century, who had focused on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural sciences, philosophy, and mathematics, rather than on such cultural texts. Arab logician, most notably Averroes, had inherited Greek ideas after they had invaded and conquered Egypt and the Levant. Their translations and commentaries on these ideas worked their way through the Arab West into Iberia and Sicily, which became important centers for this transmission of ideas. From the 11th to the 13th century, many schools dedicated to the translation of philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic to Medieval Latin were established in Iberia, most notably the Toledo School of Translators. This work of translation from Arab culture, though largely unplanned and disorganized, constituted one of the greatest transmissions of ideas in history.[199]

During the Timurid Renaissance spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries, there was a significant exchange of ideas, art, and knowledge between different cultures and civilizations. Arab scholars, artists, and intellectuals played a role in this cultural exchange, contributing to the overall intellectual atmosphere of the time. They participated in various fields, including literature, art, science, and philosophy.[200] In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Arab Renaissance, also known as the Nahda, was a cultural and intellectual movement that emerged. The term "Nahda" means "awakening" or "renaissance" in Arabic, and refers to a period of renewed interest in Arabic language, literature, and culture.[201][202][203]

Modern period

editThe modern period in Arab history refers to the time period from the late 19th century to the present day. During this time, the Arab world experienced significant political, economic, and social changes. One of the most significant events of the modern period was the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the end of Ottoman rule led to the emergence of new nation-states in the Arab world.[204][205]

Sharif Hussein was supposed, in the event of the success of the Arab revolution and the victory of the Allies in World War I, to be able to establish an independent Arab state consisting of the Arabian Peninsula and the Fertile Crescent, including Iraq and the Levant. He aimed to become "King of the Arabs" in this state, however, the Arab revolution only succeeded in achieving some of its objectives, including the independence of the Hejaz and the recognition of Sharif Hussein as its king by the Allies.[206]

Arab nationalism emerged as a major movement in the early 20th century, with many Arab intellectuals, artists, and political leaders seeking to promote unity and independence for the Arab world.[208] This movement gained momentum after World War II, leading to the formation of the Arab League and the creation of several new Arab states. Pan-Arabism that emerged in the early 20th century and aimed to unite all Arabs into a single nation or state. It emphasized on a shared ancestry, culture, history, language and identity and sought to create a sense of pan-Arab identity and solidarity.[209][210]

The roots of pan-Arabism can be traced back to the Arab Renaissance or Al-Nahda movement of the late 19th century, which saw a revival of Arab culture, literature, and intellectual thought. The movement emphasized the importance of Arab unity and the need to resist colonialism and foreign domination. One of the key figures in the development of pan-Arabism was the Egyptian statesman and intellectual, Gamal Abdel Nasser, who led the 1952 revolution in Egypt and became the country's president in 1954. Nasser promoted pan-Arabism as a means of strengthening Arab solidarity and resisting Western imperialism. He also supported the idea of Arab socialism, which sought to combine pan-Arabism with socialist principles. Similar attempts were made by other Arab leaders, such as Hafez al-Assad, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, Faisal I of Iraq, Muammar Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein, Gaafar Nimeiry and Anwar Sadat.[211]

Many proposed unions aimed to create a unified Arab entity that would promote cooperation and integration among Arab countries. However, the initiatives faced numerous challenges and obstacles, including political divisions, regional conflicts, and economic disparities.[212] The United Arab Republic (UAR) was a political union formed between Egypt and Syria in 1958, with the goal of creating a federal structure that would allow each member state to retain its identity and institutions. However, by 1961, Syria had withdrawn from the UAR due to political differences, and Egypt continued to call itself the UAR until 1971, when it became the Arab Republic of Egypt. In the same year the UAR was formed, another proposed political union, the Arab Federation, was established between Jordan and Iraq, but it collapsed after only six months due to tensions with the UAR and the 14 July Revolution. A confederation called the United Arab States, which included the UAR and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, was also created in 1958 but dissolved in 1961.[213] Later attempts to create a political and economic union among Arab countries included the Federation of Arab Republics, which was formed by Egypt, Libya, and Syria in the 1970s but dissolved after five years due to political and economic challenges. Muammar Gaddafi, the leader of Libya, also proposed the Arab Islamic Republic with Tunisia, aiming to include Algeria and Morocco,[214] instead the Arab Maghreb Union was formed in 1989.[215]

During the latter half of the 20th century, many Arab countries experienced political upheaval and conflicts, including, revolutions. The Arab-Israeli conflict remains a major issue in the region, and has resulted in ongoing tensions and periodic outbreaks of violence. In recent years, the Arab world has faced new challenges, including economic and social inequalities, demographic changes, and the impact of globalization.[216] The Arab Spring was a series of pro-democracy uprisings and protests that swept across several countries in the Arab world in 2010 and 2011. The uprisings were sparked by a combination of political, economic, and social grievances and called for democratic reforms and an end to authoritarian rule. While the protests resulted in the downfall of some long-time authoritarian leaders, they also led to ongoing conflicts and political instability in other countries.[217]

References

edit- ^ Gray, Louis Herbert (2006) Introduction to Semitic Comparative Linguistics

- ^ Courtenay, James John (2009) The Language of Palestine and Adjacent Regions

- ^ Kienast, Burkhart. (2001). Historische semitische Sprachwissenschaft.

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995) The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

- ^ Murtonen, A. (1967). Early Semitic: A Diachronical Inquiry Into the Relationship of Ethiopic to the Other So-called South-East Semitic Languages. Brill Archive.

- ^ a b Postgate, J. N. (2007). Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern. British School of Archaeology in Iraq. ISBN 978-0-903472-21-0.

- ^ Jallad, Ahmad (2018). "The earliest stages of Arabic and its linguistic classification".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Aaron D. Rubin (2008). "The subgrouping of the Semitic languages". Language and Linguistics Compass. 2 (1): 61–84. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00044.x.

- ^ Jallad, Ahmad (2018). "The earliest stages of Arabic and its linguistic classification". In Elabbas Benmamoun; Reem Bassiouney (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Arabic Linguistics. London: Routledge.

- ^ Kitchen, A.; Ehret, C.; Assefa, S.; Mulligan, C. J. (29 April 2009). "Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identified an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1668): 2703–2710. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408. PMC 2839953. PMID 19403539.

- ^ Sabatino Moscati (January 2001). The Phoenicians. I.B. Tauris. p. 654. ISBN 978-1-85043-533-4.

- ^ Kitchen, A.; Ehret, C.; Assefa, S.; Mulligan, C. J. (29 April 2009). "Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1668): 2703–2710. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408. PMC 2839953. PMID 19403539.

- ^ Jones, Lindsay (2005). Encyclopedia of religion. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 978-0-02-865740-0.

- ^ Fredrick E. Greenspahn (2005). "Ishmael". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 7. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 4551–4552. ISBN 9780028657400.

ISHMAEL, or, in Hebrew, Yishmaʿeʾl; eldest son of Abraham. Ishmael's mother was Agar, an Egyptian slave-girl whom Sarah had as her maid and eventually donated to Abraham because this royal couple were aged and childless but they were unaware then of God's plan and Israel; in accordance with Mesopotamian law, the offspring of such a union would be credited to Sarah (Gn. 16:2). The name Yishmaʿeʾl is known from various ancient Semitic cultures and means "God has hearkened," suggesting that a child so named was regarded as the answer to a request. Ishmael was circumcised at the age of thirteen by Abraham and expelled with his mother Agar at the instigation of Sarah, Abraham's wife, who wanted to ensure that Isaac would be Abraham's heir (Gn. 21). In the New Testament, Paul uses this incident to symbolize the relationship between Judaism and Christianity (Gal. 4:21–31). In the Genesis account, God blessed Ishmael, promising that he would be the founder of a great nation and a "wild ass of a man" always at odds with others (Gn. 16:12). So Abraham rose up in the morning, and taking bread and a bottle of water, put it upon her shoulder, and delivered the boy, and sent her away. And she departed, and wandered in the wilderness of Bersabee. [15] And when the water in the bottle was spent, she cast the boy under one of the trees that were there. Genesis chapter 21: [16] And she went her way, and sat over against him a great way off as far as a bow can carry, for she said: I will not see the boy die: and sitting over against, she lifted up her voice and wept. [17] And God heard the voice of the boy: and an angel of God called to Agar from heaven, saying: What art thou doing, Agar? fear not: for God hath heard the voice of the boy, from the place wherein he is. [18] Arise, take up the boy, and hold him by the hand: for I will make him a great nation. [19] And God opened her eyes: and she saw a well of water, and went and filled the bottle, and gave the boy to drink. [20] And God was with him: and he grew, and dwelt in the wilderness, and became a young man, an archer. [21] And he dwelt in the wilderness of Pharan, and his mother took a wife for him out of the land of Egypt. [22] At the same time Abimelech, and Phicol the general of his army said to Abraham: God is with thee in all that thou dost. [23] Swear therefore by God, that thou wilt not hurt me, nor my posterity, nor my stock: but according to the kindness that I have done to thee, thou shalt do to me, and to the land wherein thou hast lived a stranger. [24] And Abraham said: I will swear. [25] And he reproved Abimelech for a well of water, which his servants had taken away by force. [26] And Abimelech answered: I knew not who did this thing: and thou didst not tell me, and I heard not of it till today. [27] And Abraham took sheep and oxen and gave them to Abimelech: and both of them made a league. [28] And Abraham set apart seven ewe lambs of the flock. [29] And Abimelech said to him: What mean these seven ewe lambs which thou hast set apart? [30] But he said: Thou shalt take seven ewe lambs at my hand: that they may be a testimony for me, that I dug this well. [31] Therefore that place was called Bersabee: because there both of them did swear. [32] And they made a league for the well of oath. [33] And Abimelech, and Phicol the general of his army arose and returned to the land of the Palestines. But Abraham planted a grove in Bersabee, and there called upon the name of the Lord God eternal. [34] And he was a sojourner in the land of the Palestines many days. [Genesis 21:1-34]Douay Rheims Bible. He is credited with twelve sons, described as "princes according to their tribes" (Gn. 25:16), representing perhaps an ancient confederacy. The Ishmaelites, vagrant traders closely related to the Midianites, were apparently regarded as his descendants. The fact that Ishmael's wife and mother are both said to have been Egyptian suggests close ties between the Ishmaelites and Egypt. According to Genesis 25:17, Ishmael lived to the age of 137. Islamic tradition tends to ascribe a larger role to Ishmael than does the Bible. He is considered a prophet and, according to certain theologians, the offspring whom Abraham was commanded to sacrifice (although surah Judaism has generally regarded him as wicked, although repentance is also ascribed to him. According to some rabbinic traditions, his two wives were Aisha and Fatima, whose names are the same as those of Muhammad's wife and daughter Both Judaism and Islam see him as the ancestor of Arab peoples. Bibliography A survey of the Bible's patriarchal narratives can be found in Nahum M. Sarna's Understanding Genesis (New York, 1966). Postbiblical traditions, with reference to Christian and Islamic views, are collected in Louis Ginzberg's exhaustive Legends of the Jews, 2d ed., 2 vols., translated by Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin (Philadelphia, 2003). Frederick E. Greenspahn (1987 and 2005)

- Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brannon M. (April 2010). The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461718956.

- "Ishmael and Isaac". www.therefinersfire.org.

- ^ A–Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism, Wheeler, Ishmael

- ^ Sajjadi, Sadeq (2015) [2008]. "Abraham". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica. Vol. 1. Translated by Negahban, Farzin. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_COM_0028. ISBN 978-90-04-16860-2. ISSN 1875-9823.

- ^ Siddiqui, Mona. "Ibrahim – the Muslim view of Ibrahim". Religions. BBC. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Sajjadi, Sadeq (2015) [2008]. "Abraham". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica. Vol. 1. Translated by Negahban, Farzin. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_COM_0028. ISBN 978-90-04-16860-2. ISSN 1875-9823.

- ^ Siddiqui, Mona. "Ibrahim – the Muslim view of Ibrahim". Religions. BBC. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Strawn 2000a, p. 1205.

- ^ "Jews and Arabs Share Recent Ancestry". www.science.org. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Confirmed Cousins, Jews and Arabs Genetically and Anciently Linked | Israel - Between The Lines". 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Nebel, Almut; Filon, Dvora; Weiss, Deborah A.; Weale, Michael; Faerman, Marina; Oppenheim, Ariella; Thomas, Mark G. (December 2000). "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews" (PDF). Human Genetics. 107 (6): 630–641. doi:10.1007/s004390000426. PMID 11153918. S2CID 8136092.

According to historical records part, or perhaps the majority, of the Muslim Arabs in this country descended from local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD (Shaban 1971; Mc Graw Donner 1981). These local inhabitants, in turn, were descendants of the core population that had lived in the area for several centuries, some even since prehistorical times (Gil 1992)... Thus, our findings are in good agreement with the historical record...

- ^ Doron M. Behar; Bayazit Yunusbayev; Mait Metspalu; Ene Metspalu; Saharon Rosset; Jüri Parik; Siiri Rootsi; Gyaneshwer Chaubey; Ildus Kutuev; Guennady Yudkovsky; Elza K. Khusnutdinova; Oleg Balanovsky; Olga Balaganskaya; Ornella Semino; Luisa Pereira; David Comas; David Gurwitz; Batsheva Bonne-Tamir; Tudor Parfitt; Michael F. Hammer; Karl Skorecki; Richard Villems (July 2010). "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people". Nature. 466 (7303): 238–42. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..238B. doi:10.1038/nature09103. PMID 20531471. S2CID 4307824.

- ^ Atzmon, G; et al. (2010). "Abraham's Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry". American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (6): 850–859. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015. PMC 3032072. PMID 20560205.

- ^ Nebel (2000), quote: By the fifth century AD, the majority of non-Jews and Jews had become Christians by conversion (Bachi 1974). The first millennium AD was marked by the immigration of Arab tribes, reaching its climax with the Moslem conquest from the Arabian Peninsula (633–640 AD). This was followed by a slow process of Islamization of the local population, both of Christians and Jews (Shaban 1971; Mc Graw Donner 1981). Additional minor demographic changes might have been caused by subsequent invasions of the Seljuks, Crusaders, Mongols, Mamelukes and Ottoman Turks. Recent gene-flow from various geographic origins is reflected, for example, in the heterogeneous spectrum of globin mutations among Israeli Arabs (Filon et al. 1994). Israeli and Palestinian Arabs share a similar linguistic and geographic background with Jews. (p.631) According to historical records part, or perhaps the majority, of the Moslem Arabs in this country descended from local inhabitants, mainly Christians and Jews, who had converted after the Islamic conquest in the seventh century AD (Shaban 1971; Mc Graw Donner 1981). These local inhabitants, in turn, were descendants of the core population that had lived in the area for several centuries, some even since prehistorical times (Gil 1992). On the other hand, the ancestors of the great majority of present-day Jews lived outside this region for almost two millennia. Thus, our findings are in good agreement with historical evidence and suggest genetic continuity in both populations despite their long separation and the wide geographic dispersal of Jews.(p.637)

- ^ Kalmar, Ivan (2016-03-21), "4. Jews, Cousins Of Arabs: Orientalism, Race, Nation, And Pan-Nation In The Long Nineteenth Century", 4. Jews, Cousins Of Arabs: Orientalism, Race, Nation, And Pan-Nation In The Long Nineteenth Century, De Gruyter, pp. 53–74, doi:10.1515/9783110416596-005/html?lang=en, ISBN 978-3-11-041659-6, retrieved 2023-06-08

- ^ Nebel A, Filon D, Brinkmann B, Majumder PP, Faerman M, Oppenheim A (November 2001). "The Y chromosome pool of Jews as part of the genetic landscape of the Middle East". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (5): 1095–112. doi:10.1086/324070. PMC 1274378. PMID 11573163.

- ^ Elman, Miriam F.; Shams, Raeefa Z. (2022-10). ""We Are Cousins. Our Father Is Abraham…": Combating Antisemitism and Anti-Zionism with the Abraham Accords". Religions. 13 (10): 901. doi:10.3390/rel13100901. ISSN 2077-1444.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Rabbi Sacks: The Arabs Are Our Cousins, Not The Muslims". Israel Forever Foundation. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Thursday, Moshe Sokolow •; October 18; 2012. "Jewish Ideas Daily » Daily Features » Cousins: Jews and Arabs Seek Each Other Out". www.jewishideasdaily.com. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

{{cite web}}:|last3=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Harrison, Donald H. (2021-05-19). "Opinion: Jews, Arabs Ancient Cousins; Let's Bind Up Each Other's Wounds". Times of San Diego. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Jews and Arabs: Bound by a Common History and Destiny | Jewish Voice". www.jewishvoice.org. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ As for Ishmael, I have heeded you. I hereby bless him. I will make him fertile and exceedingly numerous. He shall be the father of twelve chieftains, and I will make of him a great nation. 17:21

- ^ Genesis 17:20

- ^ "Genesis 17:20 - The Covenant of Circumcision". Bible Hub. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "12. Experiencing God's Promises (Genesis 21) | Bible.org". bible.org. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Genesis 17:20, King James Version

- ^ "Genesis Chapter 17 – Discover Books of The Bible". Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "JOKTAN - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ a b Genesis 25:1–4 (1917 Jewish Publication Society of America translation). "And Abraham took another wife, and her name was Keturah...."

- ^ 1 Chronicles 1:32–33 (1917 Jewish Publication Society of America translation). "And the sons of Keturah, Abraham’s concubine...."

- ^ Orr, James, ed. (1915). "Keturah". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Chicago: Howard-Severance Co. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Genesis 17:20

- ^ Ibn Kathir, The Beginning and the End 3, p. 323; and Ibn Khaldun, The History 2, p. 4.

- ^ Stacey, Aisha. [2013] 2020. "Signs of Prophethood in the Noble Life of Prophet Muhammad (part 1 of 2): Prophet Muhammad’s Early Life." The Religion of Islam. Retrieved 18 December 2017. § 18, p. 215.

- Gibb, Hamilton A. R., and J. H. Kramers. 1965. Shorter Encyclopedia of Islam. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 191–98

- Maalouf, Tony. Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-9363-8.

- Urbain, Olivier (2008). Music and Conflict Transformation: Harmonies and Dissonances in Geopolitics. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-528-9.

- ^ "Levity.com, Islam". Levity.com. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Arabian, Arabians, Arabs - Encyclopedia of The Bible - Bible Gateway". www.biblegateway.com. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Seif, Prof Jeffrey (2016-08-10). "Arabs in the Bible » Kehila News Israel". Kehila News Israel. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Ishmael, King of the Arabs - TheTorah.com". www.thetorah.com. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Genesis 21:14-19 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Ishmael, King of the Arabs - TheTorah.com". www.thetorah.com. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 1 Chronicles 1:29-31 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Genesis 27 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Genesis 39:1 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Judges 8:24-27 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ Genesis 25:13–15, King James Version

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 2 Chronicles 9:14 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "1 Chronicles 17". www.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "1 Chronicles 21:16 - David looked up and saw the angel of the LORD stan..." biblestudytools.com. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 1 Chronicles 22 - New International Version". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "2 Chronicles 26 – EasyEnglish Bible (EASY)". www.easyenglish.bible. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Ephʿal, I. (1976). ""Ishmael" and "Arab(s)": A Transformation of Ethnological Terms". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 35 (4): 225–235. ISSN 0022-2968.

- ^ Quran 6:86

- ^ [Quran 14:37]

- ^ Gaster, Moses (1927). "VIII". The Asatir: the Samaritan book of Moses. London: Royal Asiatic Society. OCLC 540827714.

- ^ Gaster, Moses (1927). The Asatir [microform] the Samaritan book of the "Secrets of Moses". Internet Archive. London : The Royal Asiatic society.

- ^ Josephus, Titus Flavius (1683). "ch. 12: Of Ishmael, Abraham's son; and of the Arabians posterity.". Antiquities of the Jews (in Ancient Greek). Vol. Book 1: From creation to the death of Isaac. OCLC 70357552.

- ^ Josephus, "Book I", The Antiquities of the Jews, retrieved 2023-05-02

- ^ Onkelos. "Section V. Chaiyey Sarah". Targum Onkelos (in Aramaic).

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "JCR - Comp. JPS, Targums Onkelos, Palestinian, Jerusalem - Genesis 25". juchre.org. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ "HISTORY OF THE ARABS". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Noble, John Travis. 2013. "Let Ishmael Live Before You!" Finding a Place for Hagar's Son in the Priestly Tradition. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University.

- ^ Delitzsche (1912). Assyriesche Lesestuche. Leipzig. OCLC 2008786.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Montgomery (1934). Arabia and the Bible. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania. OCLC 639516.

- ^ Winnet (1970). Ancient Records from North Arabia. pp. 51, 52. ISBN 978-0-8020-5219-3. OCLC 79767.

king of kedar (Qedarites) is named alternatively as king of Ishmaelites and king of Arabs in Assyrian Inscriptions

- ^ Stetkevychc (2000). Muhammad and the Golden Bough. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33208-0.

Assyrian records document Ishmaelites as Qedarites and as Arabs

- ^ Hamilton, Victor P. (1990). The book of Genesis ([Nachdr.] ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2309-0.

- ^ "The Arabs of North Arabia in later Pre-Islamic Times:Qedar, Nebaioth, and Others". Research Explorer The University of Manchester. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ DNa – Livius. p. DNa inscription Line 27.

- ^ Zarins, Juris. "The Archeology Fund". The Archeology Fund. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ M. Redha Bhacker and Bernadette Bhacker. "Digging in the Land of Magan". Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ Dever, W. G. (2006), Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., p. 34, ISBN 978-0-8028-4416-3

- ^ "Genesis 25:1–2". Bible Gateway. King James Version.

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. Vol. 1. Brill. 1987. p. 121. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- ^ F. Buhl, "ʿĀd", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, ed. by Paul Bearman and others, 2nd edn, 12 vols (Leiden: Brill, 1960–2005), doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0290, ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. Vol. 8. Brill. 1987. p. 1074. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- ^ "Josephus: Antiquities of the Jews, Book XV". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ "HOW TO HANDLE OPPOSITION". abidanshah.com. 2013-02-23. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ "GESHEM THE ARABIAN - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "Geshem, Gashmu | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Retsö, Jan (2003). The Arabs in antiquity : their history from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-1-315-02953-5. OCLC 857081715.

- ^ "Eyewitnesstohistory". Eyewitnesstohistory.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Ibn Khaldun and The Myth of "Arab Invasion"". Verso. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "HISTORY OF THE ARABS". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "ch. 83: Concerning the King of the Ishmaelites". Kebra Nagast (in Geez).

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "tablet". British Museum.

- ^ Transcription: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ a b Jesper Eidema, Flemming Højlundb (1993). "Trade or diplomacy? Assyria and Dilmun in the eighteenth century BC". World Archaeology. 24 (3): 441–448. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980218.

- ^ Rice, Michael (1991). Egypt's Making: The Origins of Ancient Egypt 5000-2000 BC. p. 230. ISBN 9781134492633.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Bahrain digs unveil one of oldest civilisations". BBC News. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ "Qal'at al-Bahrain – Ancient Harbour and Capital of Dilmun". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Kessler, P. L. "Kingdoms of the Arabs - Kedar / Kedarites". The History Files. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Landmarks of the Ancient Kingdom of Saba, Marib". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ a b Quran 27:6-93 Quran 27:6–93

- ^ a b Quran 34:15-18 Quran 34:15–18

- ^ a b "British Museum - The kingdoms of ancient South Arabia". 2015-05-04. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "Saba' | History, Kingdom, & Sabaeans | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher, David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition, p. 171

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon (2002-06-18). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-4956-6.

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 166. ISBN 0-8264-4956-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Quran 44:37 Quran 44:37 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ^ Quran 50:12 Quran 50:12–14

- ^ Zaidi, Asghar (2017-10-24), "Conceptualising Well-being of Older People", Well-being of Older People in Ageing Societies, Routledge, pp. 33–53, doi:10.4324/9781315234182-2, ISBN 9781315234182, retrieved 2023-03-25

- ^ Kenneth A. Kitchen The World of "Ancient Arabia" Series. Documentation for Ancient Arabia. Part I. Chronological Framework and Historical Sources p.110

- ^ "Liḥyān - ANCIENT KINGDOM, ARABIA". Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Lion Tombs of Dedan". www.saudiarabiatourismguide.com. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ^ "Liḥyān - ANCIENT KINGDOM, ARABIA". Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "History of Arabia - Sabaean and Minaean kingdoms | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ Nethanel ben Isaiah (1983). Sefer Me'or ha-Afelah (in Hebrew). Translated by Yosef Qafih. Kiryat Ono: Mechon Moshe. p. 119. OCLC 970925649.

- ^ Rossi, Irene (2014). "The Minaeans beyond Maʿīn". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 44: 111–123. ISSN 0308-8421. JSTOR 43782855.

- ^ Weimar, Jason (November 2021). "The Minaeans after Maʿīn? The latest presently dateable Minaic text and the God of Maʿīn". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 32 (S1): 376–387. doi:10.1111/aae.12176. ISSN 0905-7196. S2CID 233780447.

- ^ "Ma'in | History, Minaeans, & Temple | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ a b c d e Van Beek 1997.

- ^ a b c d Bryce 2009, p. 578.

- ^ a b c Kitchen 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Schiettecatte 2017.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Hoyland 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Sedov, Alexander V.; Bâtâyiʿ, Ahmad (1994). "Temples of Ancient Hadramawt". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 24: 183–196. ISSN 0308-8421. JSTOR 41223417.

- ^ "History of Hadramout and taradional - KINGDOM OF HADRAMOUT AHMAD AMIN THE SITE OF THE KINGDOM OF - Studocu". Studocu. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Hadhramaut | Yemen, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Arabian Peninsula, 1–500 A.D. | Chronology | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "Hadramawt | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ "History of Arabia | People, Geography, & Empire | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- ^ Playfair, Col (1867). "On the Himyaritic Inscriptions Lately brought to England from Southern Arabia". Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London. 5: 174–177. doi:10.2307/3014224. JSTOR 3014224.

- ^ Playfair, Col. (1867). "On the Himyaritic Inscriptions Lately brought to England from Southern Arabia". Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London. 5: 174–177. doi:10.2307/3014224. ISSN 1368-0366.

- ^ "Kingdom of Awsan - Academic Kids". www.academickids.com. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- ^ Incorporated, Facts On File (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438126760.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199545568.

- ^ "Herod | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Catherwood, Christopher (2011). A Brief History of the Middle East. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 9781849018074.

- ^ Bryce 2014, p. 278.

- ^ Bryce 2014, p. 359.

- ^ David F. Graf (2003). Arabs in Syria: Demography and Epigraphy. Topoi. Orient-Occident. Supplément.

- ^ Irfan Shahîd (1984). Rome and the Arabs: A Prolegomenon to the Study of Byzantium and the Arabs (Hardcover ed.). Dumbarton Oaks. p. 5. ISBN 978-0884021155.

- ^ Mark A. Chancey (2002). The Myth of a Gentile Galilee (Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series) (Hardcover ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-521-81487-1.

- ^ Zuleika Rodgers; Margaret Daly-Denton; Anne Fitzpatrick-McKinley (2009). A Wandering Galilean: Essays in Honour of Seán Freyne (Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism) (Hardcover ed.). Brill. p. 207. ISBN 978-90-04-17355-2.

- ^ Steve Mason, Life of Josephus,Brill, 2007 p.54, n.306.

- ^ Berndt Schaller, Ituraea, p.1492.

- ^ Ball, Warwick (2001), Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-11376-8 p. 98-102

- ^ Bowman, Alan; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (2005). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521301992.

- ^ "Osroëne | ancient kingdom, Mesopotamia, Asia | Britannica".

- ^ Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028659435.

- ^ "Sarah SchneiderCH/sandbox2" at Encyclopædia Iranica

The fame of Edessa in history rests, however, mainly on its claim to have been the first kingdom to adopt Christianity as its official religion. According to the legend current for centuries throughout the civilized world, Abgar Ukkama wrote to Jesus, inviting him to visit him at Edessa to heal him from sickness. In return he received the blessing of Jesus and subsequently was converted by the evangelist Addai. There is, however, no factual evidence for Christianity at Edessa before the reign of Abgar the Great, 150 years later. Scholars are generally agreed that the legend has confused the two Abgars. It cannot be proved that Abgar the Great adopted Christianity; but his friend Bardaiṣan was a heterodox Christian, and there was a church at Edessa in 201. It is testimony to the personality of Abgar the Great that he is credited by tradition with a leading role in the evangelization of Edessa.

- ^ Ring, Steven. "History of Syriac texts and Syrian Christianity - Table 1". www.syriac.talktalk.net. Archived from the original on 2018-02-27. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ^ de Jong, Albert (2013). "Hatra and the Parthian Commonwealth". Oriens et Occidens – Band 21: 143–161.

- ^ Yaqut, Geographisches Wörterbuch, ii. 263; Payne-Smith, Thesaurus Syriacus, under "Hadyab"; Hoffmann, Auszüge aus Syrischen Akten, pp. 241, 243.

- ^ Kia 2016, p. 54.

- ^ Brunner (1983b), p. 750.

- ^ Rapp (2014), p. 28.

- ^ Jullien, Christelle (2018). "Beth 'Arabaye". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.