| This is a user sandbox of Jbs1001. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

* Editing suggestions:

- Most sections have a lot of good information already--just need to add citations

- Expand Prognosis section

- Add picture

- Is everything in the article relevant to the article topic? Is there anything that distracted you?

- Yes, the excessive use of parathesis. But mostly relevant

- Is the article neutral? Are there any claims, or frames, that appear heavily biased toward a particular position?

- It remains neutral, although some claims are unsourced

- Are there viewpoints that are overrepresented, or underrepresented?

- not particularly. Perhaps too much repetition of symptoms.

- Check a few citations. Do the links work? Does the source support the claims in the article?

- At least 2 links do not working in the 1st and 5th citations.

- Is each fact referenced with an appropriate, reliable reference? Where does the information come from? Are these neutral sources? If biased, is that bias noted?

- Many primary resources and tons of points go unsourced. Needs a lot of work here!!

- Is any information out of date? Is anything missing that could be added?

- Causes and signs and symptoms need a lot of work either due to not expanding enough or unnecessary information

- Check out the Talk page of the article. What kinds of conversations, if any, are going on behind the scenes about how to represent this topic?

- Many anecdotal accounts of autonomic dysreflexia which is really helpful and important. There's advice on symptoms and causes to add as well.

- How does the way Wikipedia discuss this topic differ from the way you would talk about it grand rounds?

- I would probably like to reference new researchand use more clear cut diagnosing criteria

Intro Paragraph Redo

editOriginal

editAutonomic dysreflexia (AD), also known as autonomic hyperreflexia or mass reflex, is a potentially life-threatening condition which can be considered a medical emergency requiring immediate attention. AD occurs most often in individuals with spinal cord injuries with spinal lesions above the T6 spinal cord level, although it has been known to occur in patients with a lesion as low as T10.[1]

Acute AD is a reaction of the autonomic (involuntary) nervous system to overstimulation. It is characterized by paroxysmal hypertension (the sudden onset of severe high blood pressure) associated with throbbing headaches, profuse sweating, nasal stuffiness, flushing of the skin above the level of the lesion, slow heart rate, anxiety, and sometimes by cognitive impairment.[2] The sympathetic discharge that occurs is usually in association with spinal cord injury (SCI) or diseases such as multiple sclerosis.

AD is believed to be triggered by afferent stimuli (nerve signals that send messages back to the spinal cord and brain) which originate below the level of the spinal cord lesion. It is believed that these afferent stimuli trigger and maintain an increase in blood pressure via a sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction in muscle, skin and splanchnic (gut) vascular beds.[3]

Redo

editAutonomic dysreflexia (AD), also known as autonomic hyperreflexia or mass reflex[4], is a syndrome and medical emergency characterized by uncontrolled hypertension and bradycardia, although tachycardia is known to occur.[5] AD occurs most often in individuals with spinal cord injuries with lesions above the T6 spinal cord level, although it has been reported in patients with lesions as low as T10.[1]

The uncontrolled hypertension in AD may result in mild symptoms, such as discomfort, blurred vision and headache; However, severe hypertension may result in potentially life-threatening complications including seizure, intracranial bleed, or retinal detachment.[5]

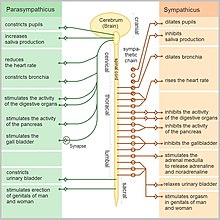

AD is triggered by either noxious or non-noxious stimuli, resulting in sympathetic stimulation and hyperactivity.[6] The most common causes include bladder or bowel over-distension, from urinary retention and fecal compaction, respectively.[7] The resulting sympathetic surge transmits through intact peripheral nerves, resulting in systemic vasoconstriction below the level of the spinal cord lesion.[8] The peripheral arterial vasoconstriction and hypertension activates the baroreceptors, resulting in a parasympathetic surge originating in the central nervous system to inhibit the sympathetic outflow; however, the parasympathetic signal is unable to transmit below the level of the spinal cord lesion.[8] This results in vasodilation, flushing, pupillary constriction and nasal stuffiness above the spinal lesion, while there's piloerection, pale and cool skin below the lesion due to the prevailing sympathetic outflow.[8]

Initial treatment involves sitting the patient upright, removing anything constrictive (clothing including), rechecking blood pressure frequently, and then checking for and removing the inciting issue, which may require urinary catheterization or bowel disimpaction.[5] If blood pressure remains elevated (over 150 mmHg) after initial steps, fast-acting short-duration antihypertensives are considered, while other inciting causes must be investigated for the symptoms to resolve.[5]

Prevention of AD involves educating the patient, family and caregivers of the precipitating cause, if known, and how to avoid it, as well as other triggers.[4] Since bladder and bowel are common causes, prevention involves routine bladder and bowel programs and urological follow-up for cystoscopy/urodynamic studies.[5]

Signs and symptoms

editThis condition is distinct and usually episodic, with the people experiencing remarkably high blood pressure (often with systolic readings over 200 mm. Hg), intense headaches, profuse sweating, facial erythema, goosebumps, nasal stuffiness, a "feeling of doom" or apprehension, and blurred vision.[9] An elevation of 40 mm Hg over baseline systolic should be suspicious for dysreflexia.

Complications

editAutonomic dysreflexia can become chronic and recurrent, often in response to longstanding medical problems like soft tissue ulcers or hemorrhoids. Long term therapy may include alpha blockers or calcium channel blockers.

Complications of severe acute hypertension can include seizures, pulmonary edema, myocardial infarction or cerebral hemorrhage. Additional organs that may be affected include the kidneys and retinas of the eyes.[9]

Redo S and S

editWhen experiencing an episode of AD, blood pressure suddenly increases in both the systolic and diastolic, with values 20 mm to 40 mm Hg above systolic baseline for adults and 15-20 mm Hg above baseline in the pediatric population with spinal cord injury.[7] Symptoms are sometimes absent despite significant hypertension.[4]

Mechanism

editSupraspinal vasomotor neurons send projections to the intermediolateral cell column, which is comprised of sympathetic preganglionic neurons (SPN) through the T1-L2 segments.[7] The supraspinal neurons act on the SPN and its tonic firing, modulating its action on the peripheral sympathetic chain ganglia and the adrenal medulla.[7] The sympathetic ganglia act directly on the blood vessels they innervate throughout the body, controlling vessel diameter and resistance, while the adrenal medulla indirectly controls the same action through the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine.[7] The descending autonomic pathways, which are responsible for the supraspinal communication with the SPN, are interrupted resulting in decreased sympathetic outflow below the level of the injury.[7] In this circumstance, the SPN is controlled only by spinal influences.[7] The the first couple weeks after a spinal injury, the decreased sympathetic outflow causes reduced blood pressure and sympathetic reflex.[7] Eventually, synaptic reorganization and plasticity of SPN develops into an overly sensitive state, which results in abnormal reflex activation of SPN due to afferent stimuli, such as bowel or bladder distension.[7] Reflex activation results in systemic vasoconstriction below the spinal cord disruption. The peripheral arterial vasoconstriction and hypertension activates the baroreceptors, resulting in a parasympathetic surge originating in the central nervous system, which inhibits the sympathetic outflow; however, the parasympathetic signal is unable to transmit below the level of the spinal cord lesion.[8] This results in vasodilation, flushing, pupillary constriction and nasal stuffiness above the spinal lesion, while there's piloerection, pale and cool skin below the lesion due to the prevailing sympathetic outflow.[8]

- ^ a b Vallès M, Benito J, Portell E, Vidal J (December 2005). "Cerebral hemorrhage due to autonomic dysreflexia in a spinal cord injury patient". Spinal Cord. 43 (12): 738–40. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101780. PMID 16010281.

- ^ Khastgir J, Drake MJ, Abrams P (May 2007). "Recognition and effective management of autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injuries". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (7): 945–56. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.7.945. PMID 17472540.

- ^ Karlsson AK (June 1999). "Autonomic dysreflexia". Spinal Cord. 37 (6): 383–91. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3100867. PMID 10432257.

- ^ a b c d Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (2002). "Acute management of autonomic dysreflexia: individuals with spinal cord injury presenting to health-care facilities". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 25 Suppl 1: S67–88. ISSN 1079-0268. PMID 12051242.

- ^ a b c d e Bradley's neurology in clinical practice. Daroff, Robert B.,, Jankovic, Joseph,, Mazziotta, John C.,, Pomeroy, Scott Loren,, Bradley, W. G. (Walter George) (Seventh edition ed.). London. ISBN 9780323287838. OCLC 932031625.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Krassioukov, Andrei; Warburton, Darren ER; Teasell, Robert; Eng, Janice J (2009-4). "A Systematic Review of the Management of Autonomic Dysreflexia Following Spinal Cord Injury". Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 90 (4): 682–695. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.017. ISSN 0003-9993. PMC 3108991. PMID 19345787.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eldahan, Khalid C.; Rabchevsky, Alexander G. (01 2018). "Autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury: Systemic pathophysiology and methods of management". Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic & Clinical. 209: 59–70. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2017.05.002. ISSN 1872-7484. PMC 5677594. PMID 28506502.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b c d e Youmans and Winn neurological surgery. Winn, H. Richard, (Seventh edition ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323287821. OCLC 963181140.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Vallès M, Benito J, Portell E, Vidal J (December 2005). "Cerebral hemorrhage due to autonomic dysreflexia in a spinal cord injury patient". Spinal Cord. 43 (12): 738–40. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101780. PMID 16010281.