|

ContactAsk in my talk page

|

Internet Hall of Fame

- Gihan Dias Sri Lanka

- Tan Tin Wee Singapore

- Hualin Qian China

- Shigeki Goto Japan

- Nabil Bukhalid Lebanon

- Haruhisa Ishida Japan

- Masaki Hirabaru Japan

- Srinivasan Ramani India

|

Communist Party of India (Marxist). |

List of JNUSU presidents

edit| President | Student Organization | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aishe Ghosh | SFI | 2019-2020 | |

| N Sai Balaji | AISA | 2018-2019 | |

| Geeta Kumari | AISA | 2017-2018 | |

| Mohit K Pandey | AISA | 2016-2017 | |

| Kanhaiya Kumar | AISF | 2015-2016 | |

| Ashutosh Kumar | AISA | 2014–2015 | |

| V Lenin Kumar/Akbar Chowdhary | 2013 | ||

| Sucheta De | 2012 | ||

| 2011 | |||

| 2010 | |||

| 2009 | |||

| 2008 | |||

| Sandeep Singh | 2007 | ||

| Dhananjay Tripathi | 2006 | ||

| 2005 | |||

| Mona Das | 2004 | ||

| Rohit | 2003 | ||

| Rohit | 2002 | ||

| Sambit Patra/ Albina Shakeel | 2001 | ||

| Sandeep Mahapatra | 2000 |

Humans of Hindutva

editType of site | Parody page |

|---|---|

| URL | www |

| Commercial | No |

| Launched | 18 April 2017[1] |

| Current status | Offline |

Humans of Hindutva (HOH) was a parody page on Facebook.[2][3] The page features satirical contents on Indian politics and Hindutva.[4][5] It has around 1 lakh followers on Facebook. The page was inspired by Humans of New York. The page was founded by an anonymous person. It was deleted by the anonymous person on 28 December 2017 citing death threats.[6][7][8]

References

edit- ^ "A Humans of New York-inspired parody is infuriating India's far right". Quartz. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ Hindutva, Humans of. "Humans of Hindutva: My Experiments With Community Standards – of Facebook and Outside - The Wire". thewire.in. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ "India at 70: Humans of Hindutva founder on ripping apart bigotry". www.dailyo.in. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ ScoopWhoop (2017-05-02). "After Humans Of Jharsa, Someone Made Humans Of Hindutva & Liberals Are Loving It". ScoopWhoop. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ "'I'm a One-Man Har*mi,' Says the Guy Who Runs 'Humans of Hindutva'". The Quint. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ Kohli, Karnika. "'Don't Want to End up Like Gauri Lankesh, Mohammed Afrazul': Humans of Hindutva Quits Facebook - The Wire". thewire.in. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ Staff, Scroll. "Creator of Humans of Hindutva deletes Facebook parody page after receiving death threats". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ "Humans of Hindutva Facebook page taken down after trolls' 'death threat' to creator". http://www.hindustantimes.com/. 2017-12-28. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: External link in|work=

Ganesh Berwal

editGanesh Berwal (Hindi: गणेश बेरवाल, born on 2 August, 1948) is an Indian archaeologist, writer and social activist.[1][2][3] He is a founder-member of Student's Federation Of India (SFI) in Rajasthan.[4]

Ganesh Berwal was arrested under the MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act) during Emergency (1975-1977).[1] During this time he was imprisoned in Sikar, Alwar and Jaipur jail for 1 year and 7 Months.[4] Berwal explored two ancient rock paintings (Hindi: शैल चित्र) in Sandhan, Nagaur, Rajasthan with Prof. Madan Lal Meena and Umro Singh (Superintendent of Archaeology Department, Kota, Government of Rajasthan).[2][5][6] He is also known for his research work on fresco paintings (Hindi: भित्ति चित्र).[2][3]

Early life

editGanesh Berwal was born in Pardoli Choti, Sikar, Rajasthan to Keshar and Balu Ram on 2nd August 1948. His grandfather Mr. Gyan Ji Patel went to Devgarh Jail during 1930 in Peasant Movement.[7] His Uncle Bhagwan Singh was Farmer Union Leader. He did primary education at home, then went to Govt. School, Rasheedpura and Seth Pannalal Chitlangiya School, Sikar for Higher Secondary Studied. After completion of school education, Berwal started graduation from Shri Kalyan Govt. P.G. College, Sikar in 1967. Beraval is married to Gauri.

Political and Social Activism

editStudents Movement

editDuring college period, Ganesh Berwal was immersed in students movement and he joined Akhil Bhartiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) in 1967, and he was appointed Sikar District Vice President of ABVP with Ghanshyam Tiwari (Secretory) and Prahalad Singh Shekhawat (President). But after 6 Month he leaved ABVP due to Ideological differences and founded Students federation of Rajasthan with Dr. Karan Singh Yadav, Ramesh Potaliya and others in mid-1967. He was the founder member of SFI (Students Federation Of India) in Rajasthan. In 1971 Berwal was State Convener of SFI Rajasthan.[4] He was elected SFI Rajasthan State General Secretory in 1972 and from 1974 to 1979 he was a member of SFI's All India Central Executive Committee.

In 1968 Rajasthan State Government started a levy on Bazra. A large peasant movement started against this levy. Farmer leader and former MLA of Rajasthan Assembly Trilok Singh was the leader of this movement and soon govt. arrested Trilok Singh.[8][9][4] In the absence of Trilok Singh Ganesh Berwal lead the movement with K.C. Jain and finally govt. withdrawn the levy.[1]

Ganesh Berwal lead a movement with Jagmal Singh (Younger Brother of former King of Sikar) for teaching in mother tongue in 1967. Jagmal Singh was the convener and Berwal was the secretory of this movement. This movement made English study optional in colleges of Rajasthan. Before this movement English study was compulsory.

Protest of Emergency (1975-1977)

editGanesh Berwal was sent to jail by the government on 4 June 1975, when he protested against the emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi. He was kept in Sikar, Alwar and Jaipur jail for 1 year and 7 Months during emergency. He was released from jail on 23 January 1977.

Member of India's Students and Youth Delegation

editHe was a member of India's delegation with Anand Sharma, Gulam Nabi Azad, Arun Jaitly, Saifuddin Choudhury, P. Madhu and others in 1978. This Indian delegation of Youth and Students went to Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Russia.[10]

A student named Kana Ram was killed by police firing in Jat Bording, Sikar on 22 April 1987. After this incident government acquired the Jat Boarding House.[11] A big mass movement took place against it. There were many leaders of this movement including Trilok Singh(Former Rajasthan MLA), Ganesh Berwal, Shyopat Singh( Former MP, Loksabha), Hari Ram Chauhan (Former Rajasthan MLA), Amara Ram (Later elected MLA from Dhod and Dantaramgarh seats of Rajasthan Assembly), Mangal Singh Yadav and others.[1] Thousands of people participated in this movement, Ganesh Berwal was the convener of the Struggle Committee (Hindi: संघर्ष समिति) for the movement. Trilok Singh, Mangal Singh and Thousands other were arrested by police for joining the movement. Later government accepted the demand of Judicial inquiry of Kana Ram's death. The movement continued for a long time, finally on 31 March 1998 the court ordered to give the possession and operational right of Jat Boarding House to an Executive Committee of 5 members, Executive committee members were Ganesh Berwal, Radmal Singh, Trilok Singh, Ramdev Singh Garhwal and Kanhiya Lal Mahala.[11] This matter was being discussed all over the India.[12] Till now the memories of this incident are in the mind of people.[13] Martyr's Day is celebrated on 22 April every year in Kana Ram's memory by his followers.[14]

In 1970 Berwal joined CPI(M) as his Political Party, from 1970 to 1988 he was the member of CPI(M) Rajasthan State Committee. In his political carrier he also fought an Election for Zila Parishad Member but he lost the Election.[15]

Prison life and lawsuits

editGanesh berwal spent more than 2 years of his life in different jails in various movements.[16] He was imprisoned in Sikar, Alwar and Jaipur jail for 1 year and 7 Months during emergency from 1975 to 1977. In 1985 he was sent in Sikar, Devli, Tonk and Jaipur Jail for 5 Months during Bizli Andolan (Hindi: बिजली आन्दोलन). Berwal was also arrested for 53 days in 1987, When he opposed the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's visit to Sikar and Nagaur.[17][18] During movements more than 40 cases were registered against him in various Police Stations of Rajasthan.[18]

Research and Writing Works

editIn late 90s Ganesh Berwal leaved the active politics and activism and he started his research and writing work in History and Archaeology.

Research in History and Archaeology

edit- Ganesh Berwal explored two ancient rock paintings (Hindi: शैल चित्र) in Sandhan, Nagaur, Rajasthan with Pro. Madan Lal Meena and Umro Singh (Superintendent of Archaeology Department, Kota, Government of Rajasthan). These rock painting are considered ten to fifteen thousand years old.[19]

- He is also a special contributor in research on Shikhawati's Fresco paintings (Hindi: भित्ति चित्र).[19]

- In view of his works done in the field of History, Archaeology and petrograph (Hindi: शिलालेख), he was appointed a member of Archaeological Monument and Historical Heritage Committee, Jaipur Division of Government of Rajasthan.

Books Written

edit- Sikar Ki Kahani Captain Web ke Jubani, 2009. [2][20]

- 'Jan Jagaran Ke Jan Nayak Kamred Mohar Singh' (Hindi: जन जागरण के जन-नायक कामरेड मोहरसिंह), 2016, ISBN 978.81.926510.7.1.[21][22][23][24]

- Aajkal Aapni Bat, Quarterly Magazine publish from Sikar, Member of Editorial board[25]

External links

editEmail to Ganesh Berwal

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Bagriya, Rameshwar (2004). Tisri Takat - Itihas, Sangharsh aur Trilok Singh (Hindi: तीसरी ताकत - इतिहास, संघर्ष और त्रिलोक सिंह). Jaipur.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d "Ganesh Berwal". Jat Land. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b VYAS, DR. ASHISH (2016). RECENT ECONOMIC DEPRESSION. JAIPUR: SHRI BHAGAWANDAS TODI PG COLLEGE. pp. 78, 79, 80.

- ^ a b c d Jangir, BrijSundar (2012). Trilok Singh - The Revolutionary Steps in Peasantry Struggle. Sikar.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ MOHIL, KAPIL (2009). SHEKHAWATI KI SHAN-SHYANAN DUNGRI DHAM. SAYANAN: KALIKA PUBLICATION.

- ^ Marudhar Ri San - Shekhawati. Shrimadhopur. Sikar: Cheeta Publication. 2016.

- ^ Thakur, Deshraj (1934). Jat Itihas (Hindi:जाट इतिहास). Delhi: Maharaja Surajmal Smarak Shiksha Shansthan.

- ^ Singh, Trilok. "Trilok Singh - Jatland Wiki". www.jatland.com. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Kaswa, Rajendra (2012). मेरा गाँव मेरा देश (वाया शेखावाटी). Jaipur: कल्पना पब्लिकेशन, जयपुर, फोन: 0141 -2317611. pp. 175, 180, 181, 203, 204. ISBN 978-81-89681-21-0.

- ^ "भारतीय प्रतिनिधि मंडल के साथ बेरवाल रूस रवाना". Dainik- Udyog Aas-Pas. 15 May 1978.

- ^ a b शताब्दी पुरुष - रणबंका रणमल सिंह, Editor Daya Ram Mahariya. Jaipur: Kalpana Publication Jaipur. 2015. ISBN 978-81-89681-21-0.

- ^ "छात्र, पुलिस और राजनीती". Maya Magazine. Summer 1987.

- ^ News, The Lallantop (16 September 2017). "अमरा राम : राजस्थान का वो विधायक जो पुलिस की गोली से बचने ऊंट पर चढ़कर भागा था". The Lallantop News. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Bhaskar, Dainik (23 April 2016). "झुंझुनूं | एसएफआईने शुक्रवार को सीकर आंदोलन में शहीद कानाराम". Dainik Bhaskar. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "कांग्रेस ने पुरे जिले में आतंक फैलाया-त्रिलोक सिंह". Dainik-Shekhawati (Dainik-Navjyoti). 25 November 1987.

- ^ "बेरवाल के न्यायिक हिरासत बढ़ी". Dainik-Udyog Aas- Pas. 31 August 1987.

- ^ "बेरवाल की न्यायिक हिरासत बढ़ी". Dainik-Udyog Aas-Pas. 1 September 1987.

- ^ a b "किसानों और छात्रों ने विरोध भी प्रकट किया". Dainik-Udyog Aas-Pas. 1 October 1987.

- ^ a b MOHIL, KAPIL (2016). SANDAN MATA KE MANDIR KA VIHANGAM DRISHYA. SANDAN: KALIKA PUBLICATION.

- ^ Berwal, Ganesh (2009). Sikar Ki Kahani - Captain Web Ki Jubani. Sikar, RJ.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bhaskar, Dainik (16 June 2017). "स्वतंत्रता सैनानी मोहरसिंह के जीवन पर लिखी पुस्तक का विमाेचन". Dainik Bhaskar. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Berwal, Ganesh (2016). 'Jan Jagaran Ke Jan Nayak Kamred Mohar Singh'(Hindi: जन जागरण के जन-नायक कामरेड मोहरसिंह). Fatehpur (Sikar) Rajasthan: Sahitya Sadan Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-926510-7-1.

- ^ "Rahar". Wikipedia. 2017-09-06 – via Reference.

- ^ Berwal, Ganesh (2016). Jan Jagaran Ke Jan Nayak Kamred Mohar Singh' (जन जागरण के जन-नायक कामरेड मोहरसिंह). Jaipur: Sahitya Sadan Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-926510-7-1.

- ^ Ajkal Aapni Bat (Summer 2016). "Ajkal Aapni Bat". Ajkal Aapni Bat.

Category:Archaeologists Category:Sikar

Suhasini Ganguly | |

|---|---|

| Born | 3 February 1909 |

| Died | 23 March 1965 |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Other names | Putudi |

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

Suhasini Ganguly (3 February 1909 - 23 March 1965) was an Indian woman freedom fighter who participated in the Indian independence movement.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Early life

editSuhasini Ganguly was born on 3rd February 1909 in Khulna, Bengal, British India to Abinashchandra Ganguly and Sarala Sundara Devi. Their family was from Bikrampur, Dhaka, Bengal. She passed matriculation in 1924 from Dhaka Eden School. While studying Intermediate of Arts, she got a teacher's job at a deaf and dumb school and went to Kolkata.[7][1][8]

Revolutionary activities

editBeginning

editWhile staying in Kolkata, she got in touch with Kalyani Das and Kamala Dasgupta. They introduced her to the Jugantar Party. She became a member of Chhatri Sangha. Under Kalyani Das and Kamala Dasgupta's management, Suhasini, on behalf of the Chhatri Sangha, taught swimming in Raja Srish Chandra Nandy's garden. There she became acquainted with revolutionary Rashik Das in 1929.[1] When the British government came to know of her activities she took refuge at Chandannagar, which was a French territory.[8]

After the Chittagong Armoury Raid on 18th April 1930, at the instruction of the leaders of the Chhatri Sangha, Sashadhar Acharya and Suhasini in a disguise of husband and wife gave shelter on May 1930 to Anant Singh, Lokenath Bal, Ananda Gupta, Jiban (Makhan) Ghoshal and others in Chandannagar. On 1st September 1930, the British raided their house and a skirmish followed. Makhan Ghoshal died in the gunfire fight and the other revolutionaries, including Suhasini Ganguly were captured.[3] But they were shortly released.[1][7]

Other activities

editShe was associated to Bina Das, who attempted to assassinate the Bengal Governor Stanley Jackson in 1932.[9]

Under the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment (BCLA) Act, she was held captive in Hijli Detention Camp from 1932 to 1938.[4][7]

After her release, she participated in India's Communist movement.[1] She was attached to the women’s front of the CPI. [10]

Though she did not participate in the Quit India Movement (as the Communist Party of India did not participate), she helped her Congress colleagues.[2] She was detained in jail between 1942 and 1945 as she gave shelter to Hemanta Tarafdar, who participated in the Quit India Movement.[1]

She was held captive for several months in 1948 and 1949 under the West Bengal Security Act of 1948 for her attachments to communism. (The Communist Party of India was banned in 1948.)[1]

Later life and death

editSuhasini was involved in social struggle throughout her life.

Due to a road accident in 1965, she was admitted to P. G. Hospital of Kolkata. But due to negligence, she became infected to tetanus and died on 23 March 1965.[1][7]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Sengupta, Subodh; Basu, Anjali (2016). Sansad Bangali Charitavidhan (Bengali). Vol. 1. Kolkata: Sahitya Sansad. p. 827. ISBN 978-81-7955-135-6.

- ^ a b Ghosh, Durba (2017-07-20). Gentlemanly Terrorists: Political Violence and the Colonial State in India, 1919–1947. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107186668.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Brigadier Samir (2013-11-12). NOTHING BUT!. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 9781482814767.

- ^ a b "Mysterious girls". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ Vohra, Asharani (1986). Krantikari Mahilae [Revolutionary Women] (in Hindi). New Delhi: Department of Publications, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 37–39.

- ^ "Book Review Swatantrata Sangram Ki Krantikari Mahilayen by Rachana Bh…". archive.is. 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ a b c d e De, Amalendu (2011). "সুহাসিনী গাঙ্গুলী : ভারতের বিপ্লবী আন্দোলনের এক উল্লেখযোগ্য চরিত্র" Suhāsinī gāṅgulī: Bhāratēra biplabī āndōlanēra ēka ullēkhayōgya caritra [Suhasini Ganguly: A notable character in the revolutionary movement of India]. Ganashakti (in Bengali).

- ^ a b Chandrababu, B. S.; Thilagavathi, L. (2009). Woman, Her History and Her Struggle for Emancipation. Bharathi Puthakalayam. ISBN 9788189909970.

- ^ Chatterjee, India (1988). "The Bengali Bhadramahila —Forms of Organisation in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). Manushi: 33–34.

- ^ Bandopadhyay, Sandip (1991). "Women in the Bengal Revolutionary Movement (1902 - 1935)" (PDF). Manushi: 34.

Category:1909 births Category:1965 deaths Category:Indian nationalists Category:Indian revolutionaries

Suniti Choudhury

editSuniti Choudhury | |

|---|---|

| Born | 22 May 1917 |

| Died | 12 January 1988 |

| Known for | Assassinating a British magistrate at age 14 |

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

Suniti Choudhury (22 May 1917 – 12 January 1988) was an Indian nationalist who, along with Santi Ghose, assassinated a British district magistrate when she was 14 years old[1][2][3] and is known for her participation in an armed revolutionary struggle.[2][4][5][6]

Early life

editSuniti Chowdhury was born on 22 May 1917 in Comilla of Comilla District of Bengal (present Bangladesh) to Umacharan Choudhury and Surasundari Choudhury[7]. She was a student of Foyjunessa Balika Vidyalay of Comilla.[8][9]

Revolutionary activities

editShe was influenced by the revolutionary activities of Ullaskar Dutta, who also lived in Comilla. She was recruited to the Jugantar Party by one of her classmates, Prafullanalini Brahma.[10] She was also the member of Tripura Zilla Chhatri Sangha. She was selected as the Captain of the Women's Volunteer Corps in the Annual Conference of Tripura Zilla Chhatri Sangha, held on 6 May 1931.[11] During this time, she was known by the alias of 'Meera Devi'. She was selected as the “custodian of firearms” and was in charge of training female members (of the Chhatri Sangha) in lathi, sword and dagger play.[12][7]

Assassination of Charles Stevens

editOn 14 December 1931, Chowdhury, then 14, and Santi Ghose, who was 15, walked into the office of Charles Geoffrey Buckland Stevens, a British bureaucrat and the district magistrate of Comilla, under the pretense that they wanted to present a petition to arrange a swimming competition amongst their classmates.[2] While Stevens looked at the document, Ghose and Chowdhury removed automatic pistols which were hidden under their shawls and shot and killed him.[2][13][14]

Trial and sentence

editThe girls were taken into custody and imprisoned in the local British jail.[2] In February 1932, Ghose and Chowdhury appeared in court in Calcutta. Being a minor, both of them were sentenced to jail for 10 years.[15] In an interview, they stated, "It is better to die than live in a horse's stable."[15][5]

She was held captive in Hijli Detention Camp as a "third class prisoner".[16] The effects of her activities were also faced by her family members. Her father’s government pension was stopped. Her two elder brothers were detained without trial. Her younger brother died from malnutrition.[8]

She was released with Santi Ghose in 1939, after having served seven years of her sentence, because of the amnesty negotiations between Gandhi and the British Indian government.[8]

Public and media response

editContemporary Western periodicals portrayed the assassination as a sign of "Indians' outrage against an ordinance by the Earl of Willingdon that suppressed the civil rights of Indians, including that of free speech."[2] Indian sources characterized the assassination as Ghose and Chowdbury's response to the "misbehaviors of the British district magistrates" who had abused their positions of power to rape Indian women.[2]

After the verdict was announced, a flyer was found by the intelligence branch of police in the Rajshahi district praising Ghose and Chowdbury as nationalist heroines. The poster read, "THOU ART FREEDOM'S NOW, AND FAME'S" and displayed photographs of the two girls alongside lines from Robert Burns' poem Scots Wha Hae[5]:

"Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty's in every blow!"

Later life and death

editAfter her release, Chowdhury studied and passed M.B.B.S. and became a doctor. In 1947, Chowdhury married Trade Union Leader Pradyot Kumar Ghosh.[8]

Chowdhury died on 12 January 1988.[8]

References

edit- ^ Forbes, Geraldine Hancock (1997). Indian Women and the Freedom Movement: A Historian's Perspective. Research Centre for Women's Studies, S.N.D.T. Women's University.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Bonnie G. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 377–8. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Brigadier Samir (2013-11-12). NOTHING BUT!. Partridge Publishing. ISBN 9781482814767.

- ^ Kamala Das Gupta (January 2015). Swadhinata Sangrame Nari (Women in the Freedom Struggle), অগ্নিযুগ গ্রন্থমালা ৯. Kolkata: র্যাডিক্যাল ইম্প্রেশন. p. ১২০-১২৪. ISBN 978-81-85459-82-0.

- ^ a b c Guhathakurta, Meghna; Schendel, Willem van (2013-04-30). The Bangladesh Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822353188.

- ^ Vohra, Asharani (1986). Krantikari Mahilae [Revolutionary Women] (in Hindi). New Delhi: Department of Publications, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b "826. Sudhin Kumar (1918-1984), 827. Suniti Choudhury, Ghosh (1917-1988)". radhikaranjan.blogspot.in. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ a b c d e Sengupta, Subodh; Basu, Anjali (2016). Sansad Bangali Charitavidhan (Bengali). Vol. 2. Kolkata: Sahitya Sansad. p. 445. ISBN 978-81-7955-135-6.

- ^ Trailokyanath Chakravarty, Jele Trish Bachhar: Pak-Bharater Swadhinata Sangram, ধ্রুপদ সাহিত্যাঙ্গন, ঢাকা, ঢাকা বইমেলা ২০০৪, পৃষ্ঠা ১৮২।

- ^ Rajesh, K. Guru. Sarfarosh: A Naadi Exposition of the Lives of Indian Revolutionaries. Notion Press. ISBN 9789352061730.

- ^ Ghosh, Ratna (2006). Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Indian Freedom Struggle: Subhas Chandra Bose : his ideas and vision. Deep & Deep. ISBN 9788176298438.

- ^ "Mysterious girls". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ "INDIA: Bengal Pains". Time. 1931-12-28. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ "WOMEN KILL MAGISTRATE". Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 - 1954). 1931-12-17. p. 37. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ a b "INDIA: I & My Government". Time. 1932-02-08. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ "দেশের প্রথম মহিলা জেল এখন আই আই টি'র গুদামঘর!". Ganashakti/Bengali. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

Anatoly Lavrentiev

editAnatoly Lavrentiev Анатолий Иосифович Лаврентьев | |

|---|---|

| |

| People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 8 March 1944 – 13 March 1946 | |

| Premier | Joseph Stalin |

| Preceded by | Georgy Chicherin |

| Succeeded by | None—post abolished |

| Ambassador of the Soviet Union to Bulgaria | |

| In office 1939–1940 | |

| Preceded by | Fyodor Raskolnikov |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Andreyevich Lavrishev |

| Ambassador of the Soviet Union to the People's Republic of Romania | |

| In office 1940–1941 | |

| Ambassador of the Soviet Union to Yugoslavia | |

| In office 1946–1949 | |

| Ambassador of the Soviet Union to Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 1951–1952 | |

| Preceded by | Mikhail Silin |

| Succeeded by | Aleksandr Bogomolov |

| Ambassador of the Soviet Union to the People's Republic of Romania | |

| In office 1952–1953 | |

| Ambassador of the Soviet Union to Iran | |

| In office 1953–1956 | |

| Preceded by | Ivan Sadchikov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1904 Russian Empire |

| Died | 1984 Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Soviet |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Profession | Diplomat, civil servant |

Anatoly Iosifovich Lavrentiev (1904 - 1984) was a Soviet diplomat. He served as the head of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs of the Russian SFSR in the Soviet government from 8 March, 1944 to 13 March, 1946. He was a member of the CPSU (b).[1]

Biography

editLavrentiev graduated from the Moscow Power Engineering Institute in 1931, then taught there.[2]

From 1938 to 1939, he worked as an employee of the apparatus of the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry of the USSR.

In 1939 he was the head of the Eastern European department of the USSR People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs.

From 1939 to 1940 he was the ambassador of the USSR in Bulgaria.

From 1940 to 1941 years he served as Plenipotentiary representative of the USSR in Romania.

In 1941 he served as the Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Envoy of the USSR in Romania.

From 1941 to 1943, he served as a responsible officer of the TASS.

In 1943 he served as the Head of the European Department of the USSR People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs.

From 1943 to 1944 he served as Head of the Middle East Department of the USSR People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs.

From 1944 to 1946 he served as People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the Russian SFSR.

From 1946 to 1949 he served as Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of the USSR in Yugoslavia.[3]

From 1949 to 1951 he served as Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR.

From 1951 to 1952 he served as Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of the USSR in Czechoslovakia.[4]

From 1952 to 1953 he served as Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of the USSR in Romania.[5]

From 1953 to 1956 he served as Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of the USSR in Iran. He met Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddeq in 1953 and brought forth the Soviet agenda in Iran. After the fall of Mosaddeq in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, he tried to commit suicide. He was briefly withdrawn but again reinstalled and returned to his post in Iran. [6][7][8][9]

From 1956 to 1970 years he served as an employee of the central apparatus of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b "03589". www.knowbysight.info. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ "Л -Ле - Свод персоналий (Игорь Абросимов) / Проза.ру". www.proza.ru. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ Smith, Bonnie G. (2005). Women's History in Global Perspective. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252072499.

- ^ Gasiorowski, Mark J.; Byrne, Malcolm (2004). Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630180.

- ^ "MOSCOW REPLACES ENVOY TO RUMANIA; Kavtaradze Relieved After 8 Years by Lavrentiev in Latest of Changes". The New York Times. 1952-07-07. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ Agrawal, Lion M. G. (2008). Freedom fighters of India. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 9788182054721.

- ^ Zahedi, Ardeshir (2012-03-21). Memoirs of Ardeshir Zahedi, Volume One: From Childhood to the End of My Father's Premiership (1928-1954). Ibex Publishers. ISBN 9781588140739.

- ^ Project, Mossadegh. "Flight of Shah In Iran Strengthens Red's Hand | Aug. 18, 1953". The Mossadegh Project. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (2015-12-16). "Unseen images of the 1953 Iran coup – in pictures". the Guardian. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

Category:Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Bulgaria Category:Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Romania Category:Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Yugoslavia Category:Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Czechoslovakia Category:Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Iran Category:Russia stubs

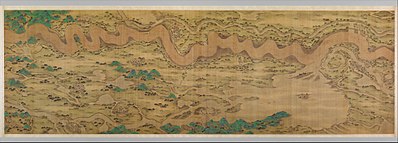

Ten Thousand Miles along the Yellow River

edit| Ten Thousand Miles along the Yellow River | |

|---|---|

| Chinese: 清 佚名 黃河萬里圖 卷 | |

| |

| Artist | Unidentified Artist; Chinese, active late 17th–early 18th century |

| Year | 1690–1722 |

| Type | Painting |

| Medium | Ink, color, and gold on silk |

| Subject | Yellow River |

| Dimensions | 78 cm × 1285 cm (31 in × 506 in) |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City |

| Accession | 2006.272a, b |

Ten Thousand Miles along the Yellow River (Chinese: 清 佚名 黃河萬里圖 卷) is a Chinese scroll painting by an unidentified artist. The painting is from the period of Qing Dynasty and is thought to be created from 1690 to 1722. The painting illustrates the Yellow River System. Currently, the work is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, where the drawing was purchased in 2006 with the help of W. M. Keck Foundation, The Dillon Fund and other donors.[1][2][3][4][5]

Given the constant threat of flooding from the Yellow River, the study and management of that river system was one of the highest priorities of the Qing court. This monumental map graphically illustrates the complexity of controlling the Yellow River's channel and its potential impact on the numerous towns and cities in its drainage area.[1]

This was painted during the reign of Kangxi emperor (reign: 1662–1722). This map reflects the highest level of indigenous mapmaking before the introduction of European techniques. (Kangxi emperor had shortly engaged a team of Jesuit missionaries to conduct a comprehensive survey of his empire.) The map's appeal lies not in its cartographic accuracy but in its pictorial treatment of terrain features. The map merges panoramic landscape painting and cartography: waterways are rendered in a planimetric fashion (that is, they lie flat on the picture surface); mountains are depicted frontally; and architecture, notably walled towns and cities, are shown as isometric projections. There is no consistent use of foreshortening, perspective, atmospheric distortion, or diminution of scale to suggest spatial recession. One may speak of the bottom or top of the composition, but there is no measurable distinction between the foreground and the far distance. The map is visually coherent, and its seemingly unbounded view of vast expanses enables the viewer to grasp far more than the eye could see in reality. To unroll the scrolls is to vicariously experience the drama of voyaging up the Yellow River from the East China Sea to the rapids of the Dragon Gate. [1]

Gallery

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Unidentified Artist | Ten Thousand Miles along the Yellow River | China | Qing dynasty (1644–1911) | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ Ghosh, Ratna (2006). Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Indian Freedom Struggle: Subhas Chandra Bose : his ideas and vision. Deep & Deep. ISBN 9788176298438.

- ^ "Mysterious girls". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ "INDIA: Bengal Pains". Time. 1931-12-28. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ "WOMEN KILL MAGISTRATE". Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 - 1954). 1931-12-17. p. 37. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

Category:17th-century works Category:18th-century works Category:Rivers in art Category:Paintings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Category:Qing dynasty paintings

Dohar (band)

editDohar (দোহার) is an Indian folk music musical ensemble that specializes in the styles of greater Bengal as well as the North East India.[1][2] It is very popular in the Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and in Bangladesh.[3][4]

Dohar has popularised Bengali and Assamese folk music. They have played for various Bengali communities in India[5] and abroad[6].

Kalikaprasad Bhattacharjee was the lead singer and leader of Dohar. Bhattacharya died in a road accident near Gurap village in Hooghly district on 7 March 2017, aged 47.[7] 5 other members were also injured.[8] The remaining members of the band have continued singing.[9]

History

editThe group was founded on 7 August 1999. The name of the band - 'Dohar' was given by Aveek Majumdar, Professor of Jadavpur University. Dohar means 'chorus'.[8]

- Kalikaprasad Bhattacharjee.

- Amit Sur,

- Rittik Guchait,

- Mrignabhi Chattopadhyay,

- Satyajit Sarkar,

- Niranjan Haldar,

- Rajib Das

- Sudipto Chakraborty.

- Soumya

- “Bandhur Deshey” by Concord Music – 2001

- “Banglar gaan Shikorer Taan” by SONY Music – 2002

- “Rupsagare” by SAREGAMA HMV – 2004

- “Bangla” by SAREGAMA HMV – 2006

- “2007” by SAREGAMA HMV – 2007

- “MATI’SWAR” by ORION ENTERTAINMENT- 2009

- “MATIR KELLA” – Video Album, a Musical Documentary of Folk Music of Bengal by SAREGAMA HMV -2011

- “BAUL FOKIRER RABINDRANATH” by ORION ENTERTAINMENT- 2012

- “SAHASRA DOTARA” by ORION ENTERTAINMENT- 2013

- “UNISHER DAAK” – by PICASSO ENTERTAINMENT-2015[11]

References

edit- ^ a b "Dohar – A Group of Folk Musicians". doharfolk.com. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ "দেশের প্রথম মহিলা জেল এখন আই আই টি'র গুদামঘর!". Ganashakti/Bengali. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- ^ "The Daily eSamakal". esamakal.net. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ Team, Samakal Online. "বাংলাদেশের গান গেয়েই যাত্রা 'দোহার' ব্যান্ডের". সমকাল. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ "Sway to the beats of folk tunes". The Times of India.

- ^ "Bangla folk band Dohar to perform in Dubai on May 29".

- ^ সংবাদদাতা, নিজস্ব. "গাড়ি দুর্ঘটনায় প্রয়াত দোহারের কালিকাপ্রসাদ". anandabazar.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ a b প্রতিবেদন, নিজস্ব. "মাটিতে পা রেখেই শহরের মঞ্চে লোকগান শোনাতে চেয়েছেন কালিকাপ্রসাদ". anandabazar.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ সংবাদদাতা, নিজস্ব. "জেলায় 'দোহার', নেই শুধু কালিকা". anandabazar.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ "Achievements – Dohar". doharfolk.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ "শুধু ভাষার জন্য". anandabazar.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

Category:Indian folk music groups

Ricardo Menéndez

editRicardo José Menéndez Prieto | |

|---|---|

| Born | 7 December, 1969 |

| Nationality | Venezuelan |

| Alma mater | Central University of Venezuela |

| Title | Vice-President of the Council of Planning Ministers |

| Term | 17 June 2014 |

| Predecessor | Jorge Giordani |

| Political party | United Socialist Party of Venezuela |

Ricardo José Menéndez Prieto is a professor and geographer who currently serves as Vice-President of the Council of Planning Ministers and Minister of Planning Popular Power of the Venezuelan government. https://es.wiki.x.io/wiki/Ricardo_Jos%C3%A9_Men%C3%A9ndez_Prieto

Ricardo Menéndez is a politician, geographer and Venezuelan teacher . He is the current Venezuelan Minister of Planning since the June 17 , 2014. He also held three other portfolios, University Education (2014), Industries (2011-2014) and Science, Technology and Intermediate Industries (2009-2011). https://fr.wiki.x.io/wiki/Ricardo_Men%C3%A9ndez

Life

editHe was highlighted as a student leader linked to the Movement 80 , an organization of students opposed to the decisions in university matters of the parties Acción Democrática /Democratic Action (Venezuela) and Copei . He was successful in the university community, triumphed in the elections for the presidency of the Federation of University Centers (FCU) of the Central University of Venezuela in the nineties.

He was a professor at the Central University of Venezuela . He holds a Master's Degree in Urban Planning and a Doctorate in Urban Planning (Urbanism) .

In 2009, President Hugo Chavez elected Menéndez as Minister of People's Power for Science, Technology and Intermediate Industries. Likewise, he was elected Vice-President of the Economic Productivity. 1 On January 19, 2010, he was assigned President-in-Charge of the Bolivarian Agency for Space Activities (ABAE).

On November 26, 2011, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez created by national decree the Ministry of Popular Power of Industries and appointed Ricardo Menéndez as minister a day earlier. 2

On April 21, 2013, national chain is reaffirmed as Minister of Industries of the Bolivarian Government of Venezuela for the government of Nicolás Maduro . 3 4 And a few months later they change their position within the cabinet being appointed Minister of Higher Education on 9 January 2014. 5

On June 17, 2014, President Nicolas Maduro appointed him as Minister of Planning. 6

On June 19, 2014, by Decree No. 1,059, President Nicolás Maduro appointed him as External Director of the Board of Directors of the State Company Petróleos de Venezuela , SA (PDVSA).

Vidyut Gore-Kale

edit[1][2]Vidyut Gore-Kale is an Indian woman blogger( for category "Indian Women Bloggers"). She is among India's oldest political bloggers. Her main blog - aamjanta.com was started in 2007. She is an influential person on social media, atheist, rationalist and well known for being an independent voice without any political, activist or financial affiliations and a prominent critic of Aadhaar, strong voice supporting many human rights struggles and Free Speech and right to dissent in India, publishes under a creative commons licence and supports FOSS.

She has blogged about several crimes and scams that have received recognition or legal notices under the notorious IT Rules by those she exposed.

I don't know that much about her personal life, but she had suffered domestic abuse and separated from her husband and has a disabled son who suffers from cerebral palsy (It is public knowledge).

She offers assistance to women facing domestic violence for several years now and is very big on practical strategies for women empowerment.[3]

- ^ "Blogger Vidyut Kale on being politically incorrect". femina.in. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- ^ "The real housewives of Twitter - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- ^ "Does the Blue Whale Challenge even exist? It could just be an urban legend". www.oneindia.com. Retrieved 2017-10-31.