| Merthyr Rising | |

|---|---|

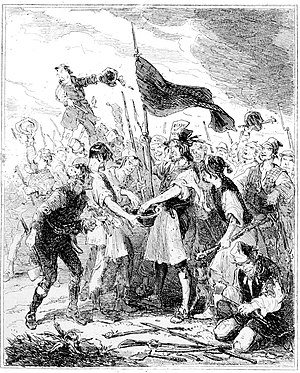

Illustration by Hablot Knight Browne depicting people raising a red flag during the Merthyr Rising of 1831 | |

| Date | June 1831 |

| Location | Merthyr Tydfil parish |

| Caused by | Lowering of wages, unemployment, the activities of the Court of Requests |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 24[1] |

| Arrested | 26[2] |

The Merthyr Rising, also referred to as the Merthyr Riots[3][4], was a worker's uprising which took place in 1831 in Merthyr Tydfil in Wales. It was a result of many years of simmering unrest among the large working class population of Merthyr and the surrounding area, most if which was employed in the local ironworking industry. It resulted in 24 deaths and 26 arrests. During the uprising, an unadorned red flag was used for the first time in Britain,[5] with some historians and politicians suggesting it as the origin of the red flag as a symbol of socialism.[6]

Background

editIronworks in Merthyr

editIronworking began in Merthyr Tydfil in the Elizabethan era.[7] Small works and blast furnaces were established in the area by several different ironmasters throughout the 16th century. The introduction of the coke fired furnace resulted in the iron industry being located in coalfield areas. The first coke fired furnace in South Wales was set up at Hirwaun in 1757, followed by the opening of the Downlais works in 1759.[7] The blast furnace there was erected by a partnership led by Isaac Wilkinson, who managed to secure an extensive lease for a small annual ground rent of £31 (equivalent to £5,998 in 2023). Partnered by John Guest, Wilkinson built another blast furnace in 1763 on land leased from the Earl of Plymouth, however due to lack of progress they decided to sell their interest in it. Anthony Bacon, a native of Cumberland, arrived in Merthyr in 1763, and two years later became the owner of the Plymouth works.[7] He also established the Cyfartha works on the banks of river Taff.[8] Each of the works had one furnace each and concentrated on producing pig iron.[7] Bacon retired in 1783, and Richard Crawshay from Normanton, West Yorkshire gained control over Cyfartha works.[7]

Crawshay discovered that the main market lay in producing bar and not pig iron, and quickly took out a license to use Henry Cort's puddling process when it was patented in 1784.[9] Production in the region was increasing rapidly, and the Merthyr ironmasters were able to raise capital to construct a canal from Merthyr to Cardiff – the Glamorganshire Canal.[9] When The Glamorganshire Canal Act was passed by Parliament in 1790, Crawshay held the biggest share of the new company.[10]

After the death of Richard Crawshey in 1810, the day to day management of the works was left to his grandson William Crawshay II, who later spent £30,000 (equivalent to £3,110,435 in 2023) of the company's capital resources to build Cyfarthfa Castle in 1825 – a vast mansion overlooking the works.[11][12] In the late 1820s John Guest, owner of the Dowlais works, managed to grow his business enough to surpass that of Crawshey.[13] In 1829, the Dowlais works had 12 furnaces, Cyfartha had 9, Plymouth and Abrdare had 7 each, Penydarren 5, Bute 3 and Gadlys had one.[14]

Worker discontent

editIn less than a century, Merthyr has grown from a village with about 40 houses to a large industrial town – this meant that most of its workforce consisted of recent immigrants. The workforce came mainly from rural Glamorgan and the depressed agricultural districts of west and mid Wales.[15] In the parish of Merther Tydfil in 1831 at least 9000 people of a population of about 27000 worked for four great iron companies.[16] Frequent short-time, serious unbalance in employment between trades and a permanent uncertainty were common in the area.[17] Workers performed heavy, taxing and dangerous work.[18] Overcrowded housing was ubiquitous, and drainage and sanitation were virtually absent.[18]

Due to frequent technical advances, accurate forecasting of market conditions has been difficult.[17] After introducing the puddling process, works were encountering a shortage of pig iron to service it. Similar bottlenecks would often follow such innovations.[17] During depressions, the Crawshay family would generally avoid wage and price cutting wars, resorting to price maintenance, stockpiling and the toleration of "over-manning" for as long as they could.[19] The consequent influx to their ironworks, especially of ironstone miners, accompanied by another depression around 1831, made the Crawshays finally cut wages which was another critical factor in the Rising.[20][21][22] William Crawshay also reluctantly dismissed 84 puddlers.[23] William Thomas Williams, the 32-year-old man who carried the Red Flag during the Rising,[24] probably the first time it was so used in Britain, was a Crawshay puddler.[23]

Additionally, there was a lot of discontent in Merthyr over the activities of the Court of Requests, a court set up for the recovery of small debts, which was believed to be acting in an oppressive manner.[21]

Before the Rising

editThe years from 1829 were years of an unprecedentedly high and sustained political temper among working people.[25] The poor rate was one of the reasons why the ironmasters would get involved in local politics.[26] At every economic crisis, whenever the poor rate rose to the threshold of alarm, the ironmasters stepped in to take over the town and impose administrative reform. In 1830, when depression coincided with national and local political crises, intervention became continuous and permanent, reform virtually total.[26]

1829 – Falling wages and rising tensions

editIn early 1829, the price of pig iron fell to £3.63 from £7.50 in 1825,[27] forcing Merthyr's ironworks to lower workers' wages.[28] William Crawshay II was the last ironmaster to lower wages, although he still paid higher than the rival ironworks of Penydarren, Dowlais, and Plymouth.[29] Following the decrease in wages, the use of the truck system increased and Dowlais' John Josiah Guest attempted to remain charitable,[30] involving himself in local affairs:[31] he built a school, a church, and housing for his community of workers.[19]

By September of that year, debt had increased within the town's working class, and the Court of Requests was required to give more credit to struggling workers.[32] Further wage cuts and the closure of a quarter of the town's furnaces continued to hit throughout the year, forcing ironworkers and shopkeepers further into debt and at risk of their belongings being seized. The Court of Requests was strongly criticised for its harsh actions in seizing property, though little could be done: the Court was too powerful for any formal complaints to succeed.[32] However, the workers' anger towards the Court pushed them towards the need to reform.[29]

1830 – Crawshay/Unitarian alliance

editIn 1830, Crawshay began to take an active part in local politics, chairing parish meetings and allowing Joseph Coffin, the Unitarian president of the Court of Requests, to become churchwarden.[30] Coffin had previously been overseer of the poor from 1812, and was responsible for lowering relief in various acts of retrenchment.[33] At the same time, the poor rate had begun to climb from three shillings and sixpence,[30] and on 16 March, Edward Littleton presented his anti-truck bill to the Commons.[34] Littleton stated that the accompanying petitions had more than 20000 signatures from "practical administrators of the law, and merchants engaged in business".[35] With the truck system seen as a serious threat to Crawshay and Plymouth's Anthony Hill, due to its prominence in Dowlais and Penydarren, they began to set up petitions against it;[36] from this formed Crawshay's alliance with the Unitarian democrats who opposed truck.[37]

While Joseph Hume defended Dowlais' reliance on truck in the Commons, Littleton was assisted by many "radicals" in his pursuits against it: Hill and Crawshay supplied anti-truck evidence; Job James, a former naval surgeon and a member of one of Merthyr's most influential Unitarian families,[38] supplied medical evidence;[39] William Milburne James (again of the James family)[37] and Edward Lewis Richards, of Lincoln's Inn and Gray's Inn respectively, gave the MP legal assistance. In June, Richards published an attack in The Cambrian on truck-using ironmasters like Dowlais' John Josiah Guest, while also praising Crawshay and Hill.[37] Both Richards and Guest were Freemasons and members of Loyal Cambrian Lodge No.110, with Guest being appointed Worshipful Master in 1840.[40]

The summer months were disastrous for the town: Dowlais and Penydarren both shut down furnaces, and Crawshay's parish reforms collapsed as Merthyr ran out of poor relief. Anger against the Court of Requests returned and ironworkers like Crawshay, whose profits were considerably down, considered parliamentary action against it.[37]

On 18 September, the anti-truck radicals returned with an article in The Cambrian,[41] written by "XYZ" (assumed to be William Milburne James[42]) and supported by "E" (Edward Lewis Richards), which criticised William Thomas the Court, a leading Merthyr Tory, and the town's "truck-doctors".[42] Specifically, it pointed out the single surgeon who was responsible for serving five ironworks (Dowlais, Penydarren, Plymouth, Rhymney and Bute) and his inability to care for such a wide-reaching area of patients.[43] The article was met with a series of retorts from "ABC" and "ET",[44][45] attacking Job James' credibility as a doctor and criticising the radical texts of Paine and Cobbett that James had distributed.[43] Colonel Brotheron himself described the radical thoughts of The Cambrian article as being "much dangerous trash" in their attempts to stir up violence.[46] He suggested that Cobbett's Twopenny Trash, which James had given out,[37] had a monthly circulation of almost two hundred, which showed the prominence of radical thought in Merthyr.[46]

The final few months of the year were marked with political discussion and public demonstrations: Crawshay was motivated again to fight against the truck system, and his London connections worked to support Littleton's parliamentary bill. On 13 November, William Milburne James chaired a meeting in the parish church in which he condemned the truck system and put forth a parliamentary petition which gained 5000 signatures.[46] By the end of November, the radicals had received over 9000 votes on a separate petition against the Corn Laws: while Crawshay had backed the earlier petition against the truck system, he was an adamant supporter of the Corn Laws because "he that knocks down corn knocks down iron". However, John Josiah Guest supported the anti-Corn Law petition due to his belief in free trade, which the Corn Laws would stop.[47][48] The petition was presented to parliament on 19 November.[49]

On 6 December, Lord Gower presented his anti-truck petition to the House of Lords.[50] On 14 December,[51] Littleton's bill had its second reading in Parliament and was supported by Crawshay and Hill's petitions. Guest, who was then MP for Honiton, proved that Dowlais' workers largely supported the truck system despite any complaints.[46]

On 23 December, the radicals called a meeting at the Bush Inn: due to 800 people attending they relied upon Joseph Coffin letting them use the parish church instead.[46] Several prominent members of the local area spoke in support of the radicals and parliamentary reform, including: Christopher James, the patriarch of the Unitarian James family;[52] E. L. Hutchins, Guest's own nephew;[47] and Dr David Rees, the former Unitarian minister.[53] David John, the current Unitarian minister and "father of Chartists",[54] launched a tirade against bishops for their lack of support for the poor, and read passages from Wade's Black Book. John's words were not received well by all, due to his strong anti-clerical views; some walked out from the meeting and others threatened action against him.[53]

1831 – The year of the Rising

editBy February, Crawshay's Unitarian allies held power over most parts of Merthyr: after complaints of corrupt constables, the Unitarians tried them for blackmail and harassment; when the poor rate went over 5 shillings, they threatened the parish clerk with dismissal.[53]

On 1 March, the Reform Bill was presented to the Commons and published: while it was not exactly what the radicals had hoped for, they supported it nonetheless.[55] A week later, on 9 March, Taliesin Williams and the James brothers called a meeting to conduct a private census of the town. After gathering population and housing information from Merthyr's 27000 people, they prepared a petition for Guest to submit in support of reform.[56]

On 8 April, a general meeting was called to discuss the idea of Merthyr being given a parliamentary seat, with radicals and ironmasters attending, alongside J. B. Bruce, a land-owning Tory in Aberdare,[57] and William Thomas the Court.[55]

Events

edit(from original article)

After storming Merthyr town, the rebels sacked the local debtors' court and the goods that had been collected. Account books containing debtors' details were also destroyed. Among the shouts were cries of Caws a bara (cheese and bread) and I lawr â'r Brenin (down with the king).

On 1 June 1831, the protesters marched to local mines and persuaded the men on shift there to stop working and join their protest. In the meantime, the British government in London had ordered in the army, with contingents of the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot dispatched to Merthyr Tydfil to restore order. Since the crowd was now too large to be dispersed, the soldiers were ordered to protect essential buildings and people.

On 2 June, while local employers and magistrates were holding a meeting with the High Sheriff of Glamorgan at the Castle Inn, a group led by Lewis Lewis (known as Lewsyn yr Heliwr) marched there to demand a reduction in the price of bread and an increase in their wages. The demands were rejected, and after being advised to return to their homes, attacked the inn. Engaged by the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot, after the rioters seized some of their weapons, the troops were commanded to open fire. After a protracted struggle in which hundreds sustained injury, some fatal, the Highlanders were compelled to withdraw to Penydarren House, and abandon the town to the rioters.

Some 7,000 to 10,000 workers marched under a red flag, which was later adopted internationally as the symbol of communists and socialists. For four days, magistrates and ironmasters were under siege in the Castle Hotel, and the protesters effectively controlled Merthyr.[58]

For eight days, Penydarren House was the sole refuge of authority. With armed insurrection fully in place in the town by 4 June, the rioters had commandeered arms and explosives, set up road-blocks, formed guerrilla detachments, and had banners capped with a symbolic loaf and dyed in blood. Those who had military experience had taken the lead in drilling the armed para-military formation, and created an effective central command and communication system.

This allowed them to control the town and engage the formal military system, including:

- Ambushing the 93rd's baggage-train on the Brecon Road, under escort of forty of the Glamorgan Yeomanry, and drove them into the Brecon hills.

- Beating off a relief force of a hundred cavalry sent from Penydarren House.

- Ambushing and disarming the Swansea Yeomanry on the Swansea Road, and throwing them back in disorder to Neath.

- Organising a mass demonstration against Penydarren House.

Having sent messengers, who had started strikes in Northern Monmouthshire, Neath and Swansea Valleys, the riots reached their peak. However, panic had spread to the family oriented and peaceful town folk, who had now started to flee what was an out-of- control town. With the rioters arranging a mass meeting for Sunday 6th, the government representatives in Penydarren House managed to split the rioters' council. When 450 troops marched to the mass meeting at Waun above Dowlais with levelled weapons, the meeting dispersed and the riots were effectively over.

Outcome

edit(from original article)

By 7 June the authorities had regained control of the town through force with up to 24 of the protesters killed.[59] Twenty-six people were arrested and put on trial for taking part in the revolt. Several were sentenced to terms of imprisonment, others sentenced to penal transportation to Australia, and two were sentenced to death by hanging – Lewis Lewis (Lewsyn yr Heliwr) for Robbery and Richard Lewis (Dic Penderyn) for stabbing a soldier (Private Donald Black of the Highland Regiment) in the leg with a seized bayonet.[60]

Lewsyn yr Heliwr's sentence was downgraded to a life sentence and penal transportation to Australia when one of the police officers who had tried to disperse the crowd testified that he had tried to shield him from the rioters. He was transported aboard the vessel John in 1832 and died 6 September 1847 in Port Macquarie, New South Wales.[citation needed]

Following this reprieve the British government, led by Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, was determined that at least one rebel should die as an example of what happened to rebels. The people of Merthyr Tydfil were convinced that Richard Lewis (Dic Penderyn) was not responsible for the stabbing, and 11,000 signed a petition demanding his release. The government refused, and Richard Lewis was hanged at Cardiff Market on August 13, 1831.[61]

In 1874, a Congregational minister, the Rev. Evan Evans, said that a man called Ianto Parker had given him a death-bed confession, saying that he had stabbed Donald Black and then fled to America fearing capture by the authorities.[62][63] James Abbott, a hairdresser from Merthyr Tydfil who had testified at Penderyn's trial, later said that he had lied under oath, claiming that he had been instructed to do so by Lord Melbourne.[62]

In creative works

editRadical singer-songwriter David Rovics included a song about the Merthyr Rising, entitled "Cheese and Bread" in the 2018 album Ballad of a Wobbly.[64]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Williams 1988, p. 18.

- ^ "Merthyr Rising, Castle Inn, High Street, Merthyr Tydfil". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Archived from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

- ^ Williams 1959, p. 124.

- ^ Carradice, Phil (25 November 2011). "A history of Welsh protest". BBC Blogs - Wales. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Johannes, Adam (2022-06-09). "'O Arglwydd, dyma Gamwedd – Oh Lord, This is an Injustice': Remembering the Merthyr Rising". Institute of Welsh Affairs. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ Timmins, Nicholas (11 August 1994). "Uprising gets red-carpet treatment: Welsh celebration marks 1831 revolt claimed as origin of the flag of socialism". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Hayman 1989, p. 8.

- ^ Ince 1993, p. 60.

- ^ a b Hayman 1989, p. 9.

- ^ Hayman 1989, p. 10.

- ^ Hayman 1989, p. 11.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 37.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 36.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Hayman 1989, p. 18.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Williams 1988, p. 49.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 51.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 38.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 39.

- ^ a b Roberts Jones 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Pelham 1886, p. 256.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 47.

- ^ "The Late Riots at Merthyr". The Cambrian. Swansea: W. C. Murray and D. Rees. 18 June 1831. p. 3. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 72.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 60.

- ^ Hyde 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 88.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Williams 1988, p. 91.

- ^ G. Williams 1966, p. 10.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 89.

- ^ Evans 1993, p. 195.

- ^ "TRUCK SYSTEM. (Hansard, 16 March 1830)". api.parliament.uk.

- ^ "TRUCK SYSTEM. (Hansard, 17 March 1830)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Crawshay, William; Hill, Anthony (19 March 1830). "National Library of Wales - The Cambrian". The Cambrian. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Williams 1988, p. 92.

- ^ G. Williams 1966, p. 14-15.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 58-59.

- ^ "FREEMASONRYATMERTHYR - The Merthyr Express". Harry Wood Southey. 1 October 1910. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "THETRUCKDOCTORSYSTEM - The Cambrian". T. Jenkins. 18 September 1830. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 92-93.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 93.

- ^ "at - The Cambrian". T. Jenkins. 9 October 1830. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "TotheEDITORofTluCAMBRIAN - The Cambrian". T. Jenkins. 25 September 1830. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Williams 1988, p. 94.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 95.

- ^ Schonhardts-Bailey 2006, p. 9.

- ^ "MINUTES. (Hansard, 19 November 1830)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "IMPERIALPARLIAMENT - The Cambrian". T. Jenkins. 11 December 1830. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ "THE TRUCK SYSTEM. (Hansard, 14 December 1830)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ G. Williams 1966, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Williams 1988, p. 96.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 74.

- ^ a b Williams 1988, p. 97.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 97, 182, 201.

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 50.

- ^ The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008.[page needed]

- ^ "1831: Merthyr Tydfil uprising". libcom.org. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ^ Pelham 1886, p. 260.

- ^ Roberts Jones 1993, p. 3.

- ^ a b Sekar 2012, p. 182.

- ^ Williams, David. "Lewis, Richard ('Dic Penderyn'; 1807/8-1831)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Cheese and Bread". Bandcamp.

Bibliography

edit- Hayman, Richard (1989). Working Iron in Merthyr Tydfil (1 ed.). Merthyr Tydfil Heritage Trust. ISBN 1871404045.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Ince, Laurence (1993). The South Wales Iron Industry 1750-1885 (1 ed.). Merton Priory Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0951816516.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Pelham, Camden (1886). The Chronicles of Crime or The New Newgate Calendar. Vol. 2. London: Reeves and Turner. LCCN 32029940.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Roberts Jones, Sally (1993). Dic Penderyn - The Man and the Martyr. Port Talabot, West Glamorgan: Goldleaf Publishing. ISBN 9780907117643.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- Williams, Gwyn A. (1959). "The Merthyr Riots: Settling the Account". National Library of Wales Journal. XI (2): 124–141. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Williams, Gwyn A. (1988) [1978]. The Merthyr Rising (2 ed.). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1783160051. LCCN 88179974.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sekar, Satish (2012). The Cardiff Five: Innocent Beyond Any Doubt. Waterside Press. ISBN 978-1-904380-76-4. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hyde, Charles K. (2019). Technological Change and the British Iron Industry, 1700-1870. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691656342.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Williams, Glanmor (1966). Merthyr Politics: The Making of a Working-Class Tradition. University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708300671.

- Evans, Chris (1993). The Labyrinth of Flames: Work and Social Conflict in Early Industrial Merthyr Tydfil. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0708311592.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Schonhardt-Bailey, C (2006). From the Corn Laws to Free Trade: interests, ideas, and institutions in historical perspective. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-19543-7; quantitative studies of the politics involved

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

External links

edit- Old Merthyr Tydfil: Dic Penderyn and the Merthyr Rising - Historical Photographs and Information Relating to the Merthyr Rising.