This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (March 2018) |

Uranium tiles have been used in the ceramics industry for many centuries, as uranium oxide makes an excellent ceramic glaze, and is reasonably abundant. In addition to its medical usage, radium was used in the 1920s and 1930s for making watch, clock and aircraft dials. Because it takes approximately three metric tons of uranium to extract 1 gram of radium, prodigious quantities of uranium were mined to sustain this new industry. The uranium ore itself was considered a waste product and taking advantage of this newly abundant resource, the tile and pottery industry had a relatively inexpensive and abundant source of glazing material. Vibrant colors of orange, yellow, red, green, blue, black, mauve, etc. were produced, and some 25% of all houses and apartments constructed[where?] during that period (circa 1920–1940) used bathroom or kitchen tiles that had been glazed with uranium. These can now be detected by a Geiger counter that detects the beta radiation emitted by uranium's decay chain.

The use of uranium in ceramic glazes in the US ceased during World War II when all uranium was diverted to the Manhattan project and didn't resume until 1959. In 1987, NCRP Report 95 indicated that no manufacturers were using uranium-glaze in dinnerware.[1]

Background

editNot long after Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity in uranium salts, Marie Curie discovered both polonium and radium as two new radioactive elements also present with uranium. The relatively high specific activity and moderate half-life of 1,600 years of 226Ra, the main radioisotope of radium found in uranium ore, made for a material which when mixed with a phosphor allowed for a glow-in-the-dark substance.

Thus, in addition to its medical usage, radium usage also became a major industry in the 1920s and 1930s for making watch, clock and aircraft dials. The radium dial painters brought a certain degree of notoriety to the abuse of radioactive materials, and that precautions needed to be followed with this new substance.

Because it takes approximately three metric tons of uranium to extract 1 gram of 226Ra, prodigious quantities of uranium were mined to sustain this new industry. The uranium ore itself was a "waste product" of this industry. By some estimates, nearly one million tons of uranium were mined to support this industry.

Taking advantage of this newly abundant resource, the tile and pottery glazing industry then had a relatively inexpensive and abundant source of glazing material that produced a wide variety of colors depending upon admixtures, firing, etc.

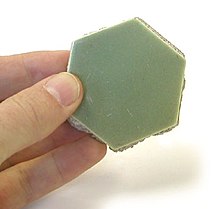

Vibrant colors of orange, yellow, red, green, blue, black, mauve, etc. were produced on tiles and other ceramic materials, and by some estimates, some 25% of all houses and apartments constructed during that period (circa 1920–1940) used varying amounts of bathroom or kitchen tiles that had been glazed with varying amounts of uranium. These can now be readily found in older homes, apartments, and other buildings still standing from that era by use of a simple Geiger counter that readily detects the beta radiation emitted by uranium's ever-present decay chain radio-daughters.[2]

After Euratom restrictions about uranium uses in ceramic glazes, there are no factories working with uranium glazes, which is why uranium glazed tiles have become rare pieces for collectors.[2]

These glazes are generally made with 238U raw material, known as yellowcake UO2 uranium granules. 21st century contemporary ceramic artist and academic researcher Sencer Sarı is one of the known specialists who is working with these uranium glazes.[3]

Health concerns

editRadioactive uranium compounds such as uranium oxide and sodium uranate) are used to impart the colors orange-red, green, yellow and black to ceramic glaze.

Although the uranium in the glaze emits gamma rays, alpha particles, and beta particles, the gamma and alpha emissions are usually too weak to be of concern.[2] The beta particles are the easiest to detect, and they are also responsible for the bulk of the radiation exposure to those handling ceramics that employ a uranium glaze.

NCRP Report 95 reported the following measurements for dinnerware employing uranium glazes: 0.2 to 20 mrad per hour on contact as measured using film badges.

NUREG/CRCP-0001 reported a measurement of approximately 0.7 mR/hr at 25 cm from a Fiesta red dinner plate. It also reported the results of an Oak Ridge National Laboratory analysis that predicted 34.4 mrem/year to a dishwasher at a restaurant using ceramic plates containing 20% uranium in the glaze, 7.9 mrem/year to the waiters, and 0.2 mrem to a patron for a four-hour exposure.

Radioactive decay leads to the presence of radon (222Rn) in the glazing which may be leached through contact with acid. Tableware with uranium glazing should not be in prolonged contact with acid foodstuff such as fruit pulp or vinegar and the glazing should not be damaged or abrased through intensive use of cutlery.[4] An FDA study[clarification needed] measured 1.66 x 10−5 uCi/ml in a 4% acetic acid solution in contact with the ceramic dinnerware for 50 hours. This exceeded the ICRP's maximum permissible concentration (MPC).

Ordinary ceramics often contain elevated levels of naturally occurring radionuclides, e.g., 40K and the various members of the uranium and thorium decay series. Because of this, health physicists who are conducting radiation surveys expect to see higher readings when they are making measurements over ceramic tiles and similar materials. Sometimes the higher readings are due to uranium in the glaze; sometimes they are due to the radionuclides in the clay that was used to produce the ceramic.

Reported examples include a vehicle carrying toilets setting off a radiation monitor at a truck weigh station, and health physicists at Oak Ridge National Laboratory reporting excessively high readings while surveying newly purchased urinals for the men's restrooms.[5]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Harry McMaster. Earthenware Dishes and Glaze Therefor. Patent No. 1,890,297,[1]

- ^ a b c msnbc.com, Alan Boyle (2003-12-12). "Uranium hunter follows trail of tiles". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- ^ "Luminescent fairies (Vilnius 2017) – Sencer Sarı".

- ^ Robert Josef Schwankner, Michael Eigenstetter, Rudolf Laubinger, Michael Schmidt (2005), "Strahlende Kostbarkeiten: Uran als Farbkörper in Gläsern und Glasuren", Physik in unserer Zeit, vol. 36, no. 4, Wiley-VCH Verlag, pp. 160–167, doi:10.1002/piuz.200501073, ISSN 0031-9252

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frame, Paul (2009-01-20). "General Information About Uranium in Ceramics". demolab.phys.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2022-08-08.