Upāli (Sanskrit and Pāli) was a monk, one of the ten chief disciples of the Buddha[1] and, according to early Buddhist texts, the person in charge of the reciting and reviewing of monastic discipline (Pāli and Sanskrit: vinaya) on the First Buddhist Council. Upāli belongs to the barber community. He met the Buddha when still a child, and later, when the Sakya princes received ordination, he did so as well. He was ordained before the princes, putting humility before caste. Having been ordained, Upāli learnt both Buddhist doctrine (Pali: Dhamma; Sanskrit: Dharma) and vinaya. His preceptor was Kappitaka. Upāli became known for his mastery and strictness of vinaya and was consulted often about vinaya matters. A notable case he decided was that of the monk Ajjuka, who was accused of partisanship in a conflict about real estate. During the First Council, Upāli received the important role of reciting the vinaya, for which he is mostly known.

Upāli | |

|---|---|

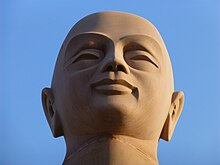

Upāli, Bodh Gaya, India | |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | all, but mostly discussed in Pāli Buddhism |

| Lineage | Vinayadhara |

| Known for | Expertise in monastic discipline, reviewed monastic discipline during the First Council |

| Other names | 'repository of the discipline' (Pali: Vinaye agganikkhitto; 'foremost in discipline' (Pali: Vinaya-pāmokkha) |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | The Buddha, Kappitaka |

| Period in office | Early Buddhism |

| Successor | Dāsaka |

Students

| |

| Initiation | Anupiyā by the Buddha |

Scholars have analyzed Upāli's role and that of other disciples in the early texts, and it has been suggested that his role in the texts was emphasized during a period of compiling that stressed monastic discipline, during which Mahākassapa (Sanskrit: Mahākāśyapa) and Upāli became the most important disciples. Later, Upāli and his pupils became known as vinayadharas (Pāli; 'custodians of the vinaya'), who preserved the monastic discipline after the Buddha's parinibbāna (Sanskrit: parinirvāṇa; passing into final Nirvana). This lineage became an important part of the identity of Ceylonese and Burmese Buddhism. In China, the 7th-century Vinaya school referred to Upāli as their patriarch, and it was believed that one of their founders was a reincarnation of him. The technical conversations about vinaya between the Buddha and Upāli were recorded in the Pāli and Sarvāstivāda traditions and have been suggested as an important subject of study for modern-day ethics in American Buddhism.

Accounts

editUpāli's personality is not depicted extensively in the texts, as the texts mostly emphasize his stereotypical qualities as an expert in monastic discipline, especially so in the Pāli texts.[2]

Early life

editAccording to the texts, Upāli was a barber, a despised profession in ancient India.[3][4] He was from an artisan class family in service to the Sakya princes in Kapilavatthu (Sanskrit: Śakya; Kapilavastu) and, according to the Mahāvastu, to the Buddha. Upāli's mother had once introduced Upāli to the Buddha.[5] The Mahāvastu, Dharmaguptaka and Chinese texts relate that as a child, Upāli shaved the hair of the Buddha. Unlike adults, he had no fear of approaching the Buddha. Once, as he was guided by the Buddha during the shaving, he attained advanced states of meditation. Buddhologist André Bareau argues that this story is ancient, because it precedes the tradition of art depictions of the Buddha with curly hair, and the glorification of Upāli as an adult.[6]

According to the Mahāvastu, the Pāli Cullavagga and the texts of discipline of the Mūlasarvāstivāda order, when the princes left home to become monks, Upāli followed them. Since the princes handed Upāli all their possessions, including jewelry, he worried that returning to Kapilavatthu with these possessions might cause him to be accused of having killed the princes for theft. Upāli therefore decided to become ordained with them. They were ordained by the Buddha at the Anupiyā grove.[7] Several variations on the story of Upāli's ordination exist, but all of them emphasize that his status in the saṅgha (Sanskrit: saṃgha; monastic community) was independent of his caste origin. In the Pāli version, the princes, including Anuruddha (Sanskrit: Aniruddha), voluntarily allowed Upāli to ordain before them in order to give him seniority in order of ordination and abandon their own attachment to class and social status.[8]

In the Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda version of the story, co-disciple Sāriputta (Sanskrit: Śāriputra) persuaded Upāli to become ordained when he hesitated because of being lower class, but in the Mahāvastu, it was Upāli's own initiative.[8][5] The Mahāvastu continues that after all the monks had been ordained, the Buddha requested that the former princes bow for their former barber, which led to consternation among the witnessing king Bimbisāra and advisers, who also bowed for Upāli following their example.[9] It became widely known that the Sakyans had their barber ordained before them to humble their pride,[10] as the Buddha related a Jātaka tale that the king and advisers had bowed for Upāli in a previous life, too.[9][11]

Indologist T.W. Rhys Davids noted that Upāli was the "striking proof of the reality of the effect produced by Gautama's disregard of the supposed importance of class".[12] Historian H.W. Schumann also raises Upāli as an example of the general rule that "in no case did ... humble origins prevent a monk from becoming prominent in the Order".[13] Religion scholar Jeffrey Samuels points out, though, that the majority of Buddhist monks and nuns during the time of the Buddha, as drawn from several analyses of Buddhist texts, were from higher classes, with a minority of six percent like Upāli being exception to the rule.[14] Historian Sangh Sen Singh argues that Upāli could have been the leader of the saṅgha after the Buddha's parinibbāna instead of Mahākassapa (Sanskrit: parinirvāṇa, Mahākāśyapa). But the fact that he was from humble origins effectively prevented this, as many of the Buddhist devotees at the time might have objected to his leadership position.[15]

Monastic life

editUpāli had a dwelling place in Vesāli (Sanskrit: Vaiśāli), called Vālikārāma.[16][17] He once asked the Buddha for leave to withdraw in the forest and lead a life in solitude. The Buddha refused, however, and told him that such a life was not for everyone. Pāli scholar Gunapala Malalasekera argued that the Buddha wanted Upāli to learn both meditation and Buddhist doctrine, and a life in the forest would have provided him with only the former. The texts state that the Buddha himself taught the vinaya (monastic discipline) to Upāli.[18] Upāli later attained the state of an enlightened disciple.[5][19]

According to the Mahāvastu, the preceptor who completed the process of Upāli's acceptance in the saṅgha was a monk called Kappitaka.[20][note 1] There is one story told about Upāli and his preceptor. Kappitaka was in the habit of living in cemeteries. In one cemetery near Vesāli he had a monastic cell. One day, a couple of nuns built a small monument there in honor of their teacher, also a nun, and made much noise in the process. Disturbed by the nuns, Kappitaka destroyed the monument, which greatly angered the nuns. Later, in an attempt to kill Kappitaka, they destroyed his cell in return. But Kappitaka was warned by Upāli in advance and he had already fled elsewhere.[22] The next day, Upāli was verbally abused by the nuns for having informed his teacher.[23]

Role in monastic discipline

editIn the literature of every Buddhist school, Upāli is depicted as an expert in vinaya and the pāṭimokkha (Sanskrit: pratimokṣa; monastic code),[5] for which the Buddha declared him foremost among those who remember the vinaya (Pali: Vinaya-pāmokkha; Sanskrit: Vinayapramukkha).[24][25] He was therefore dubbed the 'repository of the discipline' (Pali: Vinaye agganikkhitto).[19] In some schools, he is also seen as an expert in the precepts of a bodhisatta (Sanskrit: bodhisattva; Buddha-to-be).[5] 5th-century commentator Buddhaghosa stated that Upāli drew up instructions and explanatory notes for monks dealing with disciplinary matters.[19]

Upāli was also known for his strictness in practicing the discipline.[26] Monks considered it a privilege to study the vinaya under him.[27] At times, monks who felt repentance and wanted to improve themselves, sought his advice. In other cases, Upāli was consulted in making decisions considering alleged offenses of monastic discipline. For example, one newly ordained nun was found pregnant, and was judged by the monk Devadatta as unfit to be a nun. However, the Buddha had Upāli do a second investigation, during which Upāli called upon the help of the laywoman Visakhā and several other laypeople. Eventually, Upāli concluded the nun had conceived the child by her husband before her ordination as a nun, and therefore was innocent. The Buddha later praised Upāli for his careful consideration of this matter.[28]

Other notable cases about which Upāli decided are that of the monks Bharukaccha and Ajjuka. Bharukaccha consulted Upāli whether dreaming about having sex with a woman amounted to an offense that required disrobing, and Upāli judged it did not. As for the monk Ajjuka, he had decided about a dispute about real estate.[29] In this case, a rich householder was in doubt as to who he should will his inheritance to, his pious nephew or his own son. He asked Ajjuka to invite for an audience the person who had the most faith of the two—Ajjuka invited the nephew. Angry about the decision, the son accused Ajjuka of partisanship and went to see the monk Ānanda. Ānanda disagreed with Ajjuka's decision, judging the son the more rightful heir, and causing the son to feel justified in accusing Ajjuka of not being a "true monk". When Upāli got involved, however, he judged in favor of Ajjuka. He pointed out to Ānanda that the act of inviting a layperson did not break monastic discipline.[30] Eventually, Ānanda agreed with Upāli, and Upāli was able to settle the issue.[31][32] Here, too, the Buddha praised Upāli for his handling of the case.[33] Law scholar Andrew Huxley noted that Upāli's judgment of this case allowed monks to engage on an ethical level with the world, whereas Ānanda's judgment did not.[34]

First Council and death

editAccording to the chronicles, Upāli had been ordained (or, was aged[35]) forty-four years at the time of the First Buddhist Council.[36] At the council, Upāli was asked to recite the vinaya of monks and nuns, including the pāṭimokkha,[37], and the Vinayapiṭaka (collection of texts on monastic discipline) was compiled based thereon.[38] Specifically, Upāli was asked about each rule issued by the Buddha as to what it was about, where it was issued, with regard to whom, the formulation of the rule itself, derived secondary rules, and the conditions under which the rule was broken.[39] According to the Mahāsaṃghika account of the First Council, Upāli was the one who charged Ānanda, the former attendant of the Buddha, with several offenses of wrongdoing.[40]

Upāli had a number of pupils, who were called the sattarasavaggiyā.[41] Upāli and his pupils were entrusted with the safekeeping and reciting of this collection of monastic discipline.[42] Sixteen years after the Buddha's passing away, Upāli ordained a pupil called Dāsaka, who would become his successor with regard to expertise in monastic discipline. According to the late Pāli Dīpavaṃsa, Upāli died at the age of seventy-four, if this age is interpreted as life-span, not years of ordination.[35]

Previous lives

editIn some Buddhist texts, an explanation is offered why a low-caste born monk would have such a central role in developing monastic law. The question that might have been raised is whether issuing laws would not normally be associated with kings. The Apadāna explains this by relating that Upāli had been an all-powerful wheel-turning king for thousand previous lives, and a king of the deities in another thousand lives.[43] Before that, the texts say he was born during the age of Padumuttara Buddha and met one of that Buddha's disciples who was foremost in monastic discipline. Upāli aspired to be like him, and pursued it through doing merits.[19][44]

Despite Upāli's previous lives as a king, he was born as a low caste barber in the time of Gotama Buddha. This is also explained in an Apadāna story: in a previous life, Upāli insulted a paccekabuddha (Sanskrit: pratyekabuddha; a type of Buddha). The evil karma brought about low birth.[19][44]

Legacy

editUpāli was the focus of worship in ancient and medieval India and was regarded as the "patron saint" of monks who specialize in the vinaya.[5][45] He is one of the eight enlightened disciples, and is honored in Burmese ceremonies.[5][46]

Schools and lineages

editSeveral scholars have contended that the prominence of certain of the Buddha's disciples in the early texts is indicative of the preference of the compilers. Buddhologist Jean Przyluski argued that Upāli's prominence in the Pāli texts is indicative of the preference of the Sthaviravādins for vinaya above discourse, whereas the prominence of Ānanda in the Mūlasarvāstivāda texts is indicative of their preference for discourse above vinaya.[47][48] This preference of the compilers has also affected how Ānanda addresses Upāli. In many of the early discourses Upāli has little to no role, and he is not mentioned among many early lists of significant disciples. He is, however, frequently mentioned in lists in the Vinaya-piṭaka, which proves the point. Upāli seems to obtain a much more significant role with the end of the Buddha's life.[49] Przyluski's theory, which was further developed by Buddhologist André Migot, regarded Mahākassapa (Sanskrit: Mahākāśyapa), Upāli and Anuruddha (Sanskrit: Aniruddha) as part of the second period in the compiling of the early texts (4th to early 3rd century BCE) that emphasized moral discipline, associated with these disciples, as well as the city of Vesālī (Sanskrit: Vaiśalī).[note 2] In this period, these disciples' roles and stories were emphasized and embellished more than other disciples.[51] These differences in schools gradually developed and became stereotyped over time.[52]

Upāli's successors formed a lineage called the vinayadharas, or the 'custodians of the vinaya'.[53][54] Vinayadharas were monks who in early Buddhist texts were particularly known for their mastery and strictness with regard to the vinaya. In 4th–5th-century Ceylon, they then came to be associated with a lineage of such masters, because of the influence of Buddhaghosa, who established Upāli and the other vinayadharas as an important characteristic of the Mahāvihāra tradition. This concept of a vinayadhara lineage also affected Burma, and led to a belief that only those ordained in the proper lineage could become vinayadharas. Gradually, the vinayadhara came to be seen a sign of superior tradition, as the lineage was integrated with local history. Even later, the vinayadhara became a formal position of judge and arbitrator in problems of vinaya.[55]

Upāli's lineage has gained scholarly attention because of their way of timekeeping, known by modern scholars as the "dotted record". Chinese sources say that Upāli and his successors had a custom to insert a dot in a manuscript marking each year after the First Council. The sources claim that each of successors continued this tradition, up until 489 CE, when the Sarvāstivāda scholar Saṃghabhadra entered the last dot in the manuscript. This tradition has been used by some modern scholars to calculate the passing away of the Buddha, but has now been debunked as historically unlikely. Still, data pertaining to the vinayadharas is used to support theories regarding the dating of the Buddha's life and death, such as the one proposed by Indologist Richard Gombrich.[56]

Not only in ancient India did certain lineages identify with Upāli. In 7th-century China, the Vinaya or Nan-shan School was founded by the monks Ku-hsin and Tao-hsüan, seen as a continuation of Upāli's lineage. The school emphasized restoring and propagating the vinaya and became popular in the Pa Hwa Hills of Nanking. It developed a standard for teaching the vinaya. The monks would wear black and emphasized protecting oneself against error. It was believed at the time that Ku-hsin was a reincarnation of Upāli.[57]

Texts

editIn the Pāli tradition, numerous discourses show the Buddha and Upāli discussing matters of monastic discipline, including the legality of decision-making and assemblies, and the system of giving warnings and probation. Much of this is found in the Parivāra, a late vinaya text.[19] Bareau has suggested the conversation between the Buddha and Upāli about schisms was the origin of the traditions about this subject in the Vinayapiṭaka.[58] In the vinaya texts of the Sarvastivāda tradition, the Uttragrantha[59] and the 5th-century Mahāyāna-inspired Upalipariprccha[60] feature similar to almost the same questions as the Pāli Pārivāra,[61] although the suggestion that the latter originates from a no longer extant Pāli text has not been proven.[62] The Turkistan Sanskrit version of the Uttragrantha, on the other hand, does not match the Pāli at all.[61] With regard to these lists of questions, it is unknown which of these questions are from Upāli, and which were attributed to him because of his reputation.[19] Apart from these technical discussions, there is also a teaching given by Upāli referred to in the Pāli Milindapañhā.[19] Religion scholar Charles Prebish has named the Upalipariprccha as one of twenty-two texts worthy of study and practice, in order to develop American Buddhist ethics.[63]

Notes

edit- ^ Philosopher Michael Freedman argues that the office of preceptor may have only been developed after the Buddha's parinibbāna, although he admits the texts contradict each other with regard to Upāli's acceptance.[21]

- ^ Although Przyluski connected this with the city of Kosambī (Sanskrit: Kauśambī) instead.[50]

Citations

edit- ^ Ray 1994, pp. 205–206 note 2a–d.

- ^ Freedman 1977, pp. 67, 231.

- ^ Rhys Davids 1899, p. 102.

- ^ Gombrich 1995, p. 357.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mrozik 2004.

- ^ Bareau 1962, p. 262.

- ^ See Malalasekera (1937, Upāli). For the texts of traditions apart from Pāli, see Freedman (1977, p. 97).

- ^ a b Freedman 1977, p. 117.

- ^ a b Bareau 1988, p. 76.

- ^ Freedman 1977, p. 116.

- ^ Rahula 1978, p. 10.

- ^ Rhys Davids 1903, p. 69.

- ^ Schumann 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Samuels 2007, p. 123.

- ^ Singh 1973, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Upāli; Vālikārāma.

- ^ Geiger 1912, p. 35.

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Upāli; Upāli Sutta (3).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Malalasekera 1937, Upāli.

- ^ Freedman 1977, p. 58.

- ^ Freedman 1977, pp. 57 n.60, 97–98.

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Kappitaka Thera.

- ^ Dhammadinna 2016, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Sarao 2004, p. 878.

- ^ Robinson & Johnson 1997, p. 45.

- ^ Baroni 2002, p. 365.

- ^ Sarao 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Kumāra-Kassapa; Ramanīyavihārī Thera.

- ^ See Malalasekera (1937, Ajjuka; Bharukaccha). For the other laypeople, see Churn Law (2000, p. 464).

- ^ See Huxley (2010, p. 278). Freedman (1977, pp. 30–32) mentions faith, the son seeing Ānanda, and the accusation of false monkhood.

- ^ Freedman 1977, p. 32.

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Ajjuka.

- ^ Malalasekera 1961.

- ^ Huxley 2010, p. 278.

- ^ a b Prebish 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Geiger 1912, p. xlviii.

- ^ For the pāṭimokkha, see Norman (1983, pp. 7–12). For the vinaya of both monks and nuns, see Oldenberg (1899, pp. 617–618) and Norman (1983, p. 18).

- ^ Eliade 1982, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Thomas 1951, p. 28.

- ^ See Analayo (2010, p. 17 note 52). For the Mahāsaṃghika, see Analayo (2016, p. 160).

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Rājagaha.

- ^ Norman 2005, p. 37.

- ^ See Huxley (1996, p. 126 note 27) and Malalasekera (1937, Upāli). Huxley mentions the question raised.

- ^ a b Cutler 1997, p. 66.

- ^ Malalasekera 1937, Hsuan Tsang.

- ^ Strong 1992, p. 240.

- ^ Freedman 1977, pp. 13, 464–465.

- ^ Przyluski 1923, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Freedman 1977, pp. 34–35, 88–89, 110.

- ^ Przyluski 1923, p. 184.

- ^ Migot 1954, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Dutt 1925, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Sarao 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Prebish 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Frasch 1996, pp. 2–4, 12, 14.

- ^ See Prebish (2008, pp. 6–8) and Geiger (1912, p. xlvii).

- ^ For Ku-hsin, the Pa Hwa Hills, the standard and the reincarnation, see Hsiang-Kuang (1956, p. 207). For Tao-hsüan and the monks, see Bapat (1956, pp. 126–127).

- ^ Ray 1994, p. 169.

- ^ Thomas 1951, p. 268.

- ^ For the Mahāyāna influence, see Prebish (2010, p. 305) For the time period, see Agostini (2004, p. 80 n.42).

- ^ a b Norman 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Heirman 2004, p. 377.

- ^ Prebish 2000, pp. 56–57: "... texts worthy of new consideration would also include those with the richest heritage of ethical underpinnings."

References

edit- Agostini, G. (2004), "Buddhist Sources on Feticide as Distinct from Homicide", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 27 (1): 63–95, archived from the original on 24 August 2019

- Analayo, B. (2010), "Once Again on Bakkula" (PDF), The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 11: 1–28, archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2020

- Analayo, B. (2016), The Foundation History of the Nuns' Order (PDF), projekt verlag, ISBN 978-3-89733-387-1, archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2018

- Bapat, P. (1956), 2500 Years of Buddhism, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (India), OCLC 851201287

- Bareau, A. (1962), "La construction et le culte des stūpa d'après les Vinayapiṭaka" [The Construction and Cult of the Stūpa after the Vinayapiṭaka] (PDF), Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), 50 (2): 229–274, doi:10.3406/befeo.1962.1534[permanent dead link]

- Bareau, A. (1988), "Les débuts de la prédication du Buddha selon l'Ekottara-Āgama" [The beginnings of the preaching of the Buddha according to the Ekottara-Āgama], Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), 77 (1): 69–96, doi:10.3406/befeo.1988.1742

- Baroni, Helen J. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6

- Churn Law, B. (2000), A History of Pāli literature (2nd ed.), Indica Books, ISBN 81-86569-18-9

- Cutler, S.M. (1997), "Still Suffering After All These Aeons: The Continuing Effects of the Buddha's Bad Karma", in Connolly, P.; Hamilton, S. (eds.), Indian Insights: Buddhism, Brahmanism and Bhakti: Papers From the Annual Spalding Symposium on Indian Religions, Luzac Oriental, pp. 63–82, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.45, ISBN 1-898942-15-3

- Dhammadinna, B. (2016), "The Funeral of Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī and Her Followers in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya", The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies, 17: 25–74, ISSN 0972-4893, archived from the original on 2 March 2020

- Dutt, N. (1925), Early History of the Spread of Buddhism and the Buddhist Schools (PDF), Luzac & Co., OCLC 659567197

- Eliade, Mircea (1982), Histoire des croyances et des idees religieuses. Vol. 2: De Gautama Bouddha au triomphe du christianisme [A history of religious ideas: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity] (in French), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-20403-0

- Freedman, M. (June 1977), The Characterization of Ānanda in the Pāli Canon of the Theravāda: A Hagiographic Study (PDF) (PhD thesis), McMaster University, archived from the original on 19 September 2018

- Frasch, T. (1996), "An Eminent Buddhist Tradition: The Burmese Vinayadharas", Traditions in Current Perspective: Proceedings of the Conference on Myanmar and Southeast Asian Studies, 15-17 November 1995, Yangon, OCLC 835531460, archived from the original on 7 March 2020

- Geiger, W. (1912), Mahavaṃsa: Great Chronicle of Ceylon, Pali Text Society, OCLC 1049619613

- Gombrich, R.F. (1995), Buddhist Precept and Practice: Traditional Buddhism in the Rural Highlands of Ceylon, Kegan Paul, Trench and Company, ISBN 978-0-7103-0444-5

- Heirman, A. (2004), "The Chinese "Samantapāsādikā" and its school affiliation", Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 154 (2): 371–396, JSTOR 43381401

- Hsiang-Kuang, C. (1956), A History of Chinese Buddhism, Indo-Chinese Literature Publications, OCLC 553968893

- Huxley, A. (1996), "The Vinaya: Legal System or Performance-Enhancing Drug?" (PDF), The Buddhist Forum, vol. 4, School of Oriental and African Studies, pp. 1994–1996, ISBN 978-1-135-75181-4, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015

- Huxley, A. (23 June 2010), "Hpo Hlaing on Buddhist Law", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 73 (2): 269–283, doi:10.1017/S0041977X10000364, S2CID 154570006

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1937), Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names, Pali Text Society, OCLC 837021145

- Malalasekera, G. P., ed. (1961), "Ajjuka", Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, vol. 1, Government of Sri Lanka, p. 333, OCLC 2863845613[permanent dead link]

- Migot, A. (1954), "Un grand disciple du Buddha: Sāriputra. Son rôle dans l'histoire du bouddhisme et dans le développement de l'Abhidharma" [A Great Disciple of the Buddha: Sāriputra, His Role in Buddhist History and in the Development of Abhidharma] (PDF), Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), 46 (2): 405–554, doi:10.3406/befeo.1954.5607[permanent dead link]

- Mrozik, S. (2004), "Upāli", MacMillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism, vol. 1, MacMillan Reference USA, pp. 870–871, ISBN 0-02-865719-5

- Norman, K.R. (1983), Pali Literature, Otto Harrassowitz, ISBN 3-447-02285-X

- Norman, K.R. (2005), Buddhist Forum Volume V: Philological Approach to Buddhism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-75154-8

- Oldenberg, H. (1899), "Buddhistische Studien" [Buddhist Studies], Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 53 (4): 613–694, ISSN 0341-0137, JSTOR 43366938

- Prebish, C.S. (2000), "From Monastic Ethics to Modern Society", in Keown, D. (ed.), Contemporary Buddhist Ethics, Curzon, pp. 37–56, ISBN 0-7007-1278-X

- Prebish, C.S. (2008), "Cooking the Buddhist Books: The Implications of the New Dating of the Buddha for the History of Early Indian Buddhism", Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 15: 1–21, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.1275

- Prebish, C.S. (2010), Buddhism: A Modern Perspective, Penn State Press, ISBN 978-0-271-03803-2

- Przyluski, J. (1923), La légende de l'empereur Açoka [The Legend of Emperor Aśoka] (PDF) (in French), Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, OCLC 2753753

- Rahula, T. (1978), A Critical Study of the Mahāvastu, Motilal Banarsidass, OCLC 5680748

- Ray, R.A. (1994), Buddhist Saints in India: A Study in Buddhist Values and Orientations, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-507202-2

- Rhys Davids, T.W. (1899), Dialogues of the Buddha (PDF), vol. 1, Pali Text Society, OCLC 17787096

- Rhys Davids, T.W. (1903), Buddhism: A Sketch of the Life and Teachings of Gautama, the Buddha (PDF), Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, OCLC 870507941

- Robinson, R.H.; Johnson, W.L. (1997), The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction (4th ed.), Cengage, ISBN 978-0-534-20718-2

- Samuels, J. (January 2007), "Buddhism and Caste in India and Sri Lanka", Religion Compass, 1 (1): 120–130, doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2006.00013.x

- Sarao, K.T.S. (2003), "The Ācariyaparamparā and Date of the Buddha", Indian Historical Review, 30 (1–2): 1–12, doi:10.1177/037698360303000201, S2CID 141897826

- Sarao, K.T.S. (2004), "Upali", in Jestice, P.G. (ed.), Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, p. 878, ISBN 1-85109-649-3

- Schumann, H.W. (2004) [1982], Der Historische Buddha [The Historical Buddha] (in German), translated by Walshe, M. O' C., Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1817-0

- Singh, Sangh Sen (1973), "The Problem of Leadership in Early Buddhism", Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 34: 131–139, ISSN 2249-1937, JSTOR 44138606

- Strong, J.S. (1992), The Legend and Cult of Upagupta: Sanskrit Buddhism in North India and Southeast Asia, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-07389-9

- Thomas, Edward J. (1951), The History Of Buddhist Thought (2nd ed.), Routledge, OCLC 923624252