This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2024) |

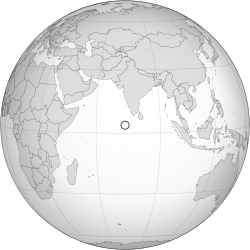

The United Suvadive Republic (Dhivehi: އެކުވެރި ސުވާދީބު ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ) was a short-lived breakaway state from the Sultanate of Maldives between 1958 and 1963,[2] consisting of the three southern atolls of the Maldive archipelago: Addu Atoll, Huvadhu Atoll and Fuvahmulah. The first president of the new nation was Abdulla Afeef Didi. The secession occurred in the context of the struggle of the Maldives’ emergence as a modern nation.[3] The United Suvadive Republic inherited a Westminster system of governance cloned from the United Kingdom, along with other institutional structures.[4]

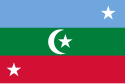

United Suvadive Republic

| |

|---|---|

| 1958–1963 | |

| Anthem: Suvadive Qaumi Salaam | |

| |

| Status | Unrecognized state |

| Capital | Hithadhoo |

| Common languages | Dhivehi |

| Religion | Islam |

| Government | Republic |

| President | |

• 1953–1963 | Abdullah Afeef Didi |

| Historical era | Post-war era |

• Independence declared | 1958 |

• Disestablished | October 1963 |

| Currency | Pound sterling[1] |

| Today part of | Maldives |

Etymology

editThe name “Suvadive” is derived from Huvadhoo Atoll. “Suvadiva”, “Suvaidu”[2] or “Suvadive” (Dhivehi: ސުވާދީބު) is the ancient name for Huvadhoo Atoll.[3][4] The early seventeenth-century French navigator François Pyrard referred to Huvadhoo as "Suadou".[5]

State of affairs

editUntil the recent history of the Maldives, the southern atolls had been more affluent (plant cover and more fertile soils, seafarers going to trade abroad) than the northern atolls (where wealth, centralized by the royal administration, came from sailor-merchants from abroad); these two ways of acquiring wealth generated two types of political power: one with despotic tendencies in the north, and a democratic sort in the south.[5]

The Crown had a monopoly on grey and black amber, as well as black coral, and hired employees to collect it. Foreign ships trading to Maldives had to report their cargo, sell whatever the Sultan of the Maldives wanted at a price he agreed to pay, and sell the rest to the people at a higher price than the crown paid.[6]

Southern atolls built fleets of 100 to 200 dead-weight tonnage long haul ships (Arumaadu Odi)[7] which were operational until the 1960s. They were fully decked with deck-houses and large overhanging forecastles.[7] Havaru Thinadhoo operated nine long haul ships, Gadhdhoo two ships, Nilandhoo three ships, and Dhaandhoo two ships with a total of 16 ships in Huvadhoo.[8] Thinadhoo was famous throughout the Indian Ocean for their frequent trips.[5] Thinadhoo was the wealthiest island in the country until it was forcefully depopulated and destroyed.[9]

There were many Maldivian ships (Arumaadu Odi) in the 19th century and during the first half of the 20th century, which traveled as far as Aden to the west and Sumatra to the east.[10]

The accumulation of wealth outside the monopoly of the Sultan enabled the southern atolls of Maldives to form as the embryo of a thalassocracy.[5]

The first President of the United Suvadive Republic, Abdulla Afeef Didi, stated in a letter to the editor of The Times in London that the forming of the new republic was not due to any outside influences.[11] It was formed with their determination to have a government elected by the people and to have economic growth which was not hindered due to influences from the Maldives monarchy.[11] Economic and Political Weekly stated that the secession was a remarkable coincidence that came with the negotiations of Gan Airport even though the Sultan of Maldives at the time accused the British of inspiring it.[12]

Overview of southern atolls

editGeography

editThe southern atolls consist of Huvadhu Atoll, Fuvahmulah and Addu Atoll. The three atolls are separated from the northern atolls by the Suvadive Channel or the Huvadu Kandu, which is the broadest channel between any atolls of the Maldives. It is known as the One and a Half Degree Channel in the British Admiralty charts.[13]

Huvadu Atoll

editHuvadu Atoll which is the largest atoll in the Maldives archipelago embracing an area of about 2,900 km2 (1,120 miles²) and around 255 islands within its boundary. It is recognized in the Guinness World Records as the Atoll with most islands in the World.[14] It is a well-defined atoll with almost a continuous rim-reef with a deep lagoon.

Huvadu population unknown in 1958

Thinadhoo population estimated at 6000[2] people in 1959. (Prior to depopulation)

Thinadhoo population estimated at 1800[15] people after resettlement on 22nd August 1966.(After depopulation in 1959)

Fuvahmulah

editFuvahmulah ('Fua Mulaku' in the Admiralty Chart) an atoll by itself with a single large island in the Equatorial Channel.

Fuahmulah population unknown in 1958.

Addu Atoll

editAddu Atoll marks the southern end of the Maldivian archipelago, and is formed with large islands on its eastern and western side fringed by broad barrier reefs.

Addu population estimated at 18,000 people in 1958.[11]

Southern aristocracy

editThe Southern Maldives aristocracy includes the intelligentsia and descendants of exiled kings of the Maldives.[3] These include Sultan Mohamed IV or Devvadhoo Rasgefaan, and those exiled includes, Sultan Hasan X, Sultan Ibrahim Mudzhiruddine[16] and descendants of Sultan Muhammed Ghiya'as ud-din.[17] This comprises the royal houses Isdu, Devvadhoo and Diyamigili. High political appointees and ex-Sultans were exiled to Fua Mulaku in the past.[2]

A majority of the chief justices who served the Kingdom of Maldives were from the southern Maldives.[3]

Prince Abdulla (later known as Ibrahim Faamuladheyri Kilegefan) was banished when he was nine years old to the southern atoll of Fuvamulah from Malé, after his father Sultan Muhammed Ghiya'asuddin was dethroned. His family’s lands were seized and his supporters were banished to islands. Sultan Muhammed Ghiya'asuddin is believed to have been killed after he returned from performing the Hajj in Mecca. Many of his descendants are from the Southern Maldives.[17]

Ibrahim Nasir, the Prime Minister of Maldives during the formation of United Suvadive Republic was born to the Southern Atoll of Fuvahmulah[18] and has the same ancestral grandfather as Afeef Didi (President of United Suvadive Republic), Ibrahim Faamuladheyri Kilegefan son of Sultan Muhammed Ghiya'as ud-din of Diyamigili Dynasty.[19]

Until enactment of 1932 constitution[20] the descendants of Sultans in Addu, Huvadhu and Fuvahmulah did not have to pay vaaru (poll tax).[2]

Governance

editThe governing bodies of the three atolls consisted of families who are related with extended families managing the atolls. Southern atolls were always self governed[2] due the southern and northern atolls being separated by the largest oceanic gap between any other atoll of Maldives, the Huvadhu Kandu. Important governing positions in the southern atolls were hereditary.[2]

Historically the Huvadu atoll chief had the privilege, not granted to any other atoll chief of the Maldives, to fly his own flag in his vessels and at his residence.[20]

Direct trade

editDirect trade among the northern atolls in the Maldives except a few affluent families from the region passed through Malé. The southern atolls of Huvadu, Fuamulak and Addu until the abolishing of the Maldives Kingdom had always traded directly with Ceylon, India and East Indies ports.[1][2]

Direct trade from the southern atolls created a wealthy mercantile class in Huvadu and Addu atolls.[1]

The Kingdom of Maldives also had no options to post agents in the southern atolls for tax collection as those atolls were too remote. Even if an agent was placed, there were no effective long-term alliance towards Malé of the person to forward the collected tax to capital. Any northern Maldivian stationed there would "go native" seeing his loyalties divide after a few years.[7]

The trading ships were called vedi in the atolls of Addu and Fuamulak and vodda in Huvadu.[7] Direct trade created a wealthy mercantile class in Southern Atolls.[1]

It was not uncommon to see long haul dead-weight 100 to 200 tonnage fleets anchored in the southern atolls. Thinadhoo of Huvadu Atoll itself had 40 of those ships which were famous throughout the Indian Ocean.[5] The southern ships were no longer built with the disruption of direct trade after United Suvadive Republic.[5]

Language

editThe southern atoll dialects are distinctly different to the northern language of Maldives.[21] Each of the three atolls has a different dialect with Huvadu atoll having variations within each island.

According to Sonja Fritz, “the dialects of Maldivian represent different diachronial stages in the development of the language. Especially in the field of morphology, the amount of archaic features steadily increase from the north to the south. Within the three southernmost atolls (of the Maldives), the dialect of the Addu islands which form the southern tip of the whole archipelago is characterized by the highest degree of archaicity”.[22] From Malé to the south up to Huvadhu Atoll, the number of archaic features increases, but from Huvadhu Atoll the archaic features decrease towards the south. The dialect of Huvadhu is characterized by the highest degree of archaicity.[22]

Causes to forming of United Suvadive Republic

editLack of elementary needs

editOne of the main reasons to the formation of United Suvadive Republic according to a letter sent by Afeef Didi to The Times of London highlighted on the indifference shown by the central government to the people of the southern atolls. This included the government providing lack of elementary needs such as food, clothing, medicine, education, and social welfare.[11][1] The letter also referred one of the reasons to taxation imposed on the people which caused revolts from those who had nothing to give.[11]

In the letter he also mentioned about the southern atolls being deprived of elementary needs such as government assigned doctors, schooling, communication facilities or public utilities. Seasonal epidemics such as flu, malaria, enteritis, typhoid, diarrhea, conjunctivitis outbreaks caused deaths annually, and when appealed to, the central government refused to help.[11]

Another reason being food prices being too high in southern atolls due to the central government selling them at high prices while purchasing southern dried fish at lower prices to be exported to Ceylon.[11]

Lack of infrastructure

editThe Maldives' economic development was hampered by a lack of land-based resources and human capital, as well as a long-standing feudal structure. The Maldives lacked the necessary infrastructure (ports, airports, hospitals, schools, harbors, and telecommunications, as well as people resources) to enter the twenty-first century as a self-sufficient nation until the late 1950s and 1960s. Even though the Maldives initially felt the impact of the industrial revolution in Europe in 1850, when Indian merchants brought luxury goods to Malé, residents on the outer islands never experienced such luxury.[4]

Lack of education

editAll the riches and education were reserved for the ruling elites and aristocracy of Malé, and islanders lived in isolation from Malé and the rest of the world.[4]

Travel restrictions

editIn addition to elitism, islanders faced other challenges. Only Malé's elites were allowed to go freely overseas for academics or business, while the rest of the Maldivians were subjected to a number of limitations.[4]

Trade restrictions

editWorld War II discouraged many from trading by ship due to the perils of war.[1]

Until then Huvadhu and Addu had established frequent trading to the ports of Colombo, Galle in Ceylon. With World War II, the central authorities had their first opportunity to impose restrictions to the southern atolls to restrict trade and gain an advantage over them.[1]

Maldives diplomats in Colombo with the co-operation of the British authorities managed to monitor the southern merchants who traded from Colombo. The central authorities in Maldives exerted requirements to carry passports for the first time in 1947 which were to be issued from Maldives. The impact to the economy due to the trade restrictions was resented by the southern merchants and population.[1]

Unfair taxation

editThe success of imposing trade restriction gave the Maldives central authorities the opportunity to impose vaaru (poll tax) and varuvaa (land tax) on the southern atolls. The restrictions on trade and the imposition of new taxing angered the population.[1] World War II had an enormous impact on the Maldives as the main export of dried fish could not be exported and lack of importation of staples caused severe privation and even famine.[2]

Trading of even single coconuts or barters to the British troops were recorded through the government by the militia officers stationed in Addu and Havaru Thinadhoo to ensure taxation was imposed.[1]

Riots due to taxing

editRiots spread across Hithadhoo on the New Year's Eve of 1959 due to the government announcing new taxation on boats. The impending disaster due to angry mobs trying to attack government facilities was informed by Abdulla Afeef Didi getting the officials to safety in British-controlled areas.[1]

Provoking of southern aristocracy

editThe final blow to the harmony of the Southern atolls were from the arrest and physical assault on Ahmed Didi by one of the officials sent from Male'. Ahmed Didi was the son of Elha Didi who was a member of the leading families of Hithadhoo.[1] Ahmed Didi was beaten until he bled from his nose and mouth. News had traveled to the community that he had been beaten to death.[23]

On this event there was an uprising against the official who beat Ahmed Didi who fled taking refuge at the British barracks.[1][23]

An investigation undertaken by the central authorities prevailed the account of events told by the person who assaulted Ahmed Didi, in turn convicted Abdulla Afeef Didi. He was sentenced to public flogging by two cat o' nine tails, and chili paste rubbed into the wounds.[1]

The investigation was said to have been overlooked by Al-Ameer Hassan Fareed who visited Addu and had soon departed to Colombo afterwards. On the way to Colombo, he met his unfortunate demise from a World War II submarine attack.[23]

The Addu nobles were accused of the death of Al-Ameer Hassan Fareed, claiming it to have been due to sorcery and were punished after they were brought to Malé.[23]

Halting of constructions in Addu atoll

editBy the end of 1957, the Sultan had appointed Ibrahim Nasir as Prime Minister. After being appointed Ibrahim Nasir had soon ordered the British to halt all construction work in Addu where an airbase and hospital was being built.[1]

Surplus of skilled workers

editPrior to forming of the new nation, hundreds of workers in Addu had modern skills. Some were foremen of electric works, construction, vehicle maintenance and even chefs and were accustomed to living in large houses with tape recorders and imported cigarettes; which were luxurious goods to Maldives at the time. The atoll also had an enormous increase of population from 6000 to 17000 within 19 years due to excellent medical service by the British. Its high skilled worker population had grown to an extent that it was no longer supported by food resources from those who lacked skills which required importation of food.[2]

Limits to southern atoll development

editAccording to Clarence Maloney in "The Maldives: New Stresses in an Old Nation", Afeef Didi stated that the Kingdom of Maldives was principally only concerned with the welfare of Malé.[2] Towns other than Malé was an alien concept to Maldivians, hence there is no word that signifies 'Town', 'City' or 'Village' in Maldivian language.[2]

The affluence of Addu and Huvadhu merchants was always resented by the mercantile classes in Malé[1] and lack of cooperation from the capital hindered and limited its economic growth.

Intentions to cut ties with Britain

editAt the time, the southern atolls benefited with cooperation with the British during the protectorate era. However, Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir wanted to cut ties with Britain, seeking both to close the RAF Gan and seek independence from the British. This was not looked at favourably by the southern atolls. As over 800 locals from the south worked at RAF Gan and the Hithadhoo Facilities. [24]

Secession of the United Suvadive Republic

editDeclaring independence by Addu atoll

editOn January 3, 1959 (some sources state the year of declaration of independence as 1958 [2]) a delegation of the Addu people arrived on Gan and declared their independence to the British. The delegation also insisted that Afeef be their leader.[25]

Formation of United Suvadive Republic

editThe three atolls Huvadu, Fuamulah and Addu formed the United Suvadive Republic by breaking away from the sovereign authority of the Sultan on 13 March 1959.[25]

Economic prosperity

editUnited Suvadive Republic established the Adduan Trading Corporation for exports and Imports, and founded the first bank in the Maldives.[2] The new British pound economy based on democratic principles boomed to a degree of prosperity unseen to its population.[1]

Economy

editThe Suvadive government’s economic policies included the establishment of the Addu Trading Corporation (ATC) to manage trade and supply needs. ATC held a monopoly on trading within the atoll, raising significant capital through public shareholding and employing over 26 staff members. The corporation facilitated trade with Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) through an agreement with an Indian businessman, ensuring the export of products like dried tuna and the import of essential goods.[26]

Huvadhu Atoll, the largest of the three atolls that made up the United Suvadive Islands, played a crucial role in the economy due to its rich fishing grounds. The atoll produced much of the higher quality (and hence higher value) tuna that was being exported from the Maldives at the time. Huvadhu’s contribution was vital for the fledgling nation’s economy, as it provided a significant portion of the exports necessary for trade.[26]

Administration

editThe administration of the United Suvadive Islands was structured around a 54-member Council, with representatives from Addu Atoll, Huvadhu Atoll, and Fuvahmulah. Addu, being the central atoll, had the most representatives. The Council met every three months to oversee governance, with an Executive Council of seven members tasked with the day-to-day administration.[26]

Each atoll was managed by an appointed chief and judge, with local governance conducted through atoll committees. In Addu, members of the People’s Council were elected, and the first presidential election was held in September 1959. The Suvadive government established various ministries, including Home Affairs, Public Safety, Justice, and Finance, and provided services such as healthcare, education, and legal adjudication.[26]

Huvadhu Atoll, known for its strong local governance and vibrant community, was integrated into this administrative framework. Delegations from Huvadhu agreed to join the new nation, contributing representatives to the Council and participating in the administrative processes. The local leaders and communities in Huvadhu worked closely with the central administration to implement policies and reforms.[26]

The Suvadive administration implemented several reforms, including registration of births, deaths, property, and businesses, and the establishment of educational institutions. Healthcare was notably advanced, with facilities provided by the RAF in Gan and a health center in Feydhoo offering free treatment to locals.[26]

Leadership of Abdullah Afeef Didi

editThe Suvadive Revolt, which began on the final night of 1958, thrust Afeef Didi into a critical leadership role. The revolt was sparked by the Maldivian government’s imposition of new taxes and restrictions on the residents of Addu Atoll, particularly those working at the British military base in Gan. The unrest quickly escalated, with local fishermen, traders, and workers uniting against the central government’s rule from Malé.[27]

Afeef Didi initially acted to protect Ahmed Zaki, the Maldivian Government Representative, and warn the British at Gan about the impending mob. Afeef Didi took direct action to protect Zaki and warn the British. However, the situation evolved rapidly, and Afeef Didi found himself deeply involved in the frantic efforts to find a suitable leader for the emerging separatist government.[27]

As the revolt intensified, the need for a local leader became urgent. The British Political advisor at Gan, Major Phillips, was already engaging with the Hithadhoo men and appeared willing to cooperate with a suitable leader. The initial suggestion of a local Pakistani camp supervisor was rejected by the British, who insisted on a local negotiator. This left only two possibilities: a man in Colombo named Ahmed Didi, and Abdullah Afeef Didi.[27]

Resignation and end of United Suvadive Republic

editIn the face of mounting pressure and insurmountable challenges, Abdullah Afeef Didi resigned from his position as President of the United Suvadive Republic. He accepted an offer of asylum from the British government and was flown to the Seychelles on 30 September 1963.[28][1]

Depopulation of Havaru Thinadhoo

editThis rebellion was further fueled by several laws enacted in the Maldives that significantly impacted the merchants of Havaru Thinadhoo. These laws included increased tariffs and a new payment mechanism for sold items, requiring transactions to pass through the Maldives government, which caused extended delays in payments to merchants. This new structure severely hindered the island’s thriving economy..[29]

Another cause of the second insurrection was the abusive behavior of Maldives government soldiers stationed in Havaru Thinadhoo.[29]

Despite additional appeals made to the Maldives government to improve conditions in Havaru Thinadhoo, no response was received. Karankaa Rasheed, a staff member of the Maldives’ People’s Majlis (parliament), stated that no such letter was ever received, and the mission to quell the insurrection was kept a state secret.[29]

On 4 February 1962 the Kingdom of Maldives reacted by sending a fully armed gunboat to Havaru Thinadhoo commanded by Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir.

Parliament of the United Suvadive Republic

editList of Addu Atoll members for the Parliament of United Suvadive Republic. The rest of the two atolls, Huvadu and Fuvahmulah, could not hold elections due to military action from the Malé government.[30]

Hithadhoo

edit17 members

| Votes | Member |

|---|---|

| 851 | Moosa Ali Didi |

| 843 | Ahmed Salih Ali Didi |

| 840 | Moosa Ahmed Didi |

| 761 | Ibrahim Abdul Hameed Didi |

| 750 | Ali Fahmy Didi |

| 734 | Kalhaage Ali Manikaa |

| 596 | Moosa Musthafaa |

| 589 | Mohamed Saeed |

| 589 | Abdulla Habeeb |

| 579 | Mohamed Ibrahim Didi |

| 524 | Hussein Ahmed |

| 523 | Ali Muruthalaa |

| 506 | Abdul Majeed Saleem |

| 487 | Abdulla Moosa Didi |

| 483 | Abdulla Azeez |

| 457 | Abdulla Ali |

| 422 | Abbeyyaage Ibrahim Didi |

Meedhoo

edit7 members

| Votes | Member |

|---|---|

| 187 | Mohamed Naseem |

| 186 | Abdullah Nafiz |

| 185 | Ibrahim Fahmy Didi |

| 182 | Abdulla Bagir |

| 157 | Mohamed Waheed |

| 144 | Mudhin Didige Mohamed Didi |

| 90 | Kadhaa Didige Abdulla Didi |

Hulhudhoo

edit8 members

| Votes | Member |

|---|---|

| 192 | Mudhin Thakhaanu |

| 174 | Mohamed Thaafeeq |

| 173 | Mohamed Ibrahim |

| 172 | Thakhaanuge Ali Thakhaan |

| 171 | Rekididige Waheed |

| 170 | Thakhaanuge Mohamed Thakhaan |

| 170 | Gaumaathage Mohamed Thakurufan |

| 151 | Ali Manikfan Kudhufokolhuge |

Gan Feydhoo

edit10 members

| Votes | Member |

|---|---|

| 362 | Dhonrahaa Khatheeb |

| 350 | Abdullah Manikfan Khatheeb |

| 350 | Dhonthuththu Khatheeb |

| 344 | Hussein Manikfan Khatheeb |

| 343 | Eedugaluge Ibrahim Manikfan |

| 336 | Eedugaluge Ahmed Manikfan |

| 298 | Beyruge Ahmed Manikfan |

| 295 | Eedugaluge Ali Manikfan |

| 198 | Zakariya Mohamed |

| 187 | Hussein Manikfan Moosa Rahaage |

Maradhoo Feydhoo

edit3 members

| Votes | Member |

|---|---|

| 135 | Ahmed Zahir Khatheeb |

| 85 | Ahmed Moosa |

| 70 | Ahmed Wafir Khatheeb |

Maradhoo

edit6 members

| Votes | Member |

|---|---|

| 218 | Moosa Khatheeb |

| 205 | Mohamed Waheed Khatheeb |

| 189 | Hassan Saeed |

| 169 | Abdullah Saeed |

| 140 | Vakarugey Dhonrahaa |

| 121 | Moosa Wajdee |

Appointed by the President of U.S.R

edit- Mohamed Ibrahim Didi

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "United Suvadive Republic". Archived from the original on 2013-02-14. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Maloney, C (9 April 1947). "The Maldives: New Stresses in an Old Nation". Far Eastern Survey. 16 (7): 654–671. doi:10.2307/2643164. JSTOR 2643164.

- ^ a b c d "Maldivesroyalfamily". Archived from the original on 2013-02-14. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e Mohamed, Ibrahim (2018). Adaptive capacity of islands of the Maldives to climate change. Adaptive Capacity of Islands of the Maldives to Climate Change (phd). p. 25. doi:10.25903/fnym-nr79.

- ^ a b c d e f g Koechlin, Bernard (1979). "Notes sur l'histoire et le navire long-courrier, odi, aujourd'hui disparu, des Maldives". Archipel. 18: 288. doi:10.3406/arch.1979.1516.

- ^ Frederick Lach, Donald. Asia in the Making of Europe: A Century of Advance: South Asia. p. 942.

- ^ a b c d e f Romero-Frias, Xavier (2016). "Rules for Maldi Vian Trading Ships Tra Velling Abroad (1925) and a Sojourn in Southern Ceylon". Politeja (40): 67–84. JSTOR 24920196.

- ^ ޢަފީފު, ޢަޒީޒާ; Afeef, Azeeeza (10 August 2020). "އައްޒަގެ ދިރާސީ ބަސް: ސުވަދުންމަތީ މީހުން އަރުމާދު އޮޑީގައި ކުރި ވިޔަފާރި ދަތުރު!". Digital repository of The Maldives National University.

- ^ ޢަފީފު, ޢަޒީޒާ; Afeef, Azeez (17 August 2020). "އައްޒަގެ ދިރާސީ ބަސް: ސުވަދުންމަތީ މީހުންގެ ނުތަނަވަސްކަމުގެ ފެށުން". Digital repository of The Maldives National University.

- ^ Doumenge, François. "Une construction navale autonome". L'Halieutique maldivienne, une ethno-culture millénaire.

- ^ a b c d e f g "President of the Suvadives: Letter to the Times". Archived from the original on 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2006-02-20.

- ^ "From 50 Years Ago". Economic and Political Weekly. 50 (31): 9. 2015. JSTOR 24482153.

- ^ "One and Half Degree Channel: Maldives".

- ^ "Guinness World Records - Most islands within an atoll".

- ^ "Siyaasee thaareekhu - Thinadhoo" (PDF).

- ^ "House of Diyamigily".

- ^ a b "Hilaalys Restored as the House of Huraa". Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2021-08-23.

- ^ "ސެޕްޓެމްބަރު 02 ގައި އުފަންވެވަޑައިގަތް ބަޠަލު". Dhidaily. 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Ibrahim Nasir: First President of the Maldives following independence in the 1960s". Independent.co.uk. 26 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Maldive Flags".

- ^ B. D, Cain (2000). Introduction. Dhivehi (Maldivian): A Synchronic and Diachronic Study (Thesis). Ithaca: Cornell University. p. 1.

- ^ a b Fritz (2002)

- ^ a b c d "ދިވެހި ސަރުކާރުން "ސުވާދީބަށް" އެންމެ ފަހަކަށް ކަނޑައެޅި "ވެރިޔާ"".

- ^ "The Sun never sets on the British Empire". Gan.philliptsmall.me.uk. 17 May 1971. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b "The Suvadive Revolt - Addu 1959". Archived from the original on 2004-08-12.

- ^ a b c d e f Shafeenaz Abdul Sattar, Sattar (March 2021). "Administration and economy of the united suadive islands-some insights".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c "Maldives Royal Family Official Website: Suvadive Revolt 1959 by O'Shea and Abdulla". maldivesroyalfamily.com. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ "The British map Maldives while maldives history timeline 1900-2006, fahuge tareek - Maldives Culture Special". 2006-02-21. Archived from the original on 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ a b c ޝަފީޤާ, އާމިނަތު (2009-11-01). 1950 ގެ އަހަރުގެ ތެރޭގައި ދެކުނުގެ ތިން އަތޮޅުގައި އުފެއްދި ބަޣާވާތް: ގދ. ހިވަރު ތިނަދޫ މީހުންގެ ދައުރު (Thesis thesis). ފެކަލްޓީ އޮފް އާޓްސް، މޯލްޑިވްސް ކޮލެޖް އޮފް ހަޔަރ އެޑިޔުކޭޝަން.

- ^ "Parliament of the United Suvadives Republic". Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

External links

edit- Symbols of the Suvadive State

- Suvadive Coat of Arms Archived 2012-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Historical Information Archived 2013-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- United Suvadive Republic Archived 2013-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Suvadive Parliament Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine