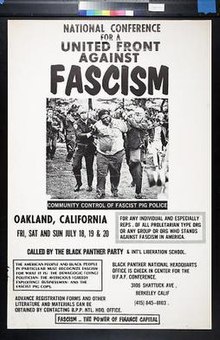

The United Front Against Fascism (UFAF) was an anti-fascist conference organized by the Black Panther Party and held in Oakland, California, from July 18 to 21, 1969.[1]

Background

editThe May 31, 1969 issue of The Black Panther called for a "Revolutionary Conference for a United Front Against Fascism," to be held in Oakland in July of that year.[2] The announcement drew links between the killing of James Rector and the imprisonment of Huey Newton, and outlined the purpose of the conference: it would develop a political program representing the "poor, black, oppressed workers and people of America", involving strategies for community control of policing, the release of political prisoners, the expulsion of the military from college and university campuses, and community self-defense.[2]

Event

editAround 5,000 people responded to the call, including members of the Communist Party USA,[3] the Peace and Freedom Party,[4] the Progressive Labor Party,[3][4] the Red Guard Party,[4] the Southern Christian Leadership Conference,[3] Students for a Democratic Society (SDS),[3][4][5] the Third World Liberation Front,[3][4] the Young Lords,[3][4] the Young Patriots Organization,[3][4] the Young Socialist Alliance[4] and various groups associated with the women's liberation movement.[4] Events took place in the Oakland Auditorium and DeFremery Park.[4] Delegates included Asian Americans, Latinos and other people of color, but the majority in attendance were white.[4] Some members of the factionalized Students for a Democratic Society were ejected from the auditorium for "disruptive behavior," and the following day distributed pamphlets which accused organizers of excluding them.[5]

Speeches were given on the first day of the congress. The second day was devoted to workshops on issues around fascism, gender, workers and students, political prisoners, health, religion, state repression of political dissent and policing.[3] Speakers included Bob Avakian[5] and Jeff Jones[6] of SDS; Elaine Brown, who presented a letter from Ericka Huggins who was at that time incarcerated;[6] the politician Ron Dellums;[6] and the lawyers Charles Garry[7] and William Kunstler,[6] the latter of whom discussed the 1967 Plainfield, New Jersey riots and argued for the legality and necessity of defensive violence.[8] Following the congress the National Committees to Combat Fascism, a national network that sought community control of police forces, was established.[3][9]

Significance

editIn 2017 the historian Robyn C. Spencer connected the UFAF to contemporary antifascism in the United States, and argued that

The history of the UFAF demonstrates that discussions about fascism in the US are nothing new. It shifts the discussion of fascism away from an American exceptionalist terrain where the US is compared with Europe and government structures or despotic leaders are analyzed and instead demonstrates the value of unearthing manifestations of fascism in the lived experiences of Black people in the US.[3]

See also

edit- Antifa (United States), a contemporary anti-fascist movement

- COINTELPRO, a series of projects conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic political organizations including the Black Panther Party

- Rainbow Coalition (Fred Hampton), a political organisation by Fred Hampton of the Black Panther Party

References

edit- ^ Bloom, Joshua; Martin, Waldo E. Jr. (2013). Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 300.

- ^ a b Bloom & Martin 2013, p. 299.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Spencer, Robyn C. (January 26, 2017). "The Black Panther Party and Black Anti-fascism in the United States". Duke University Press. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bloom & Martin 2013, p. 300.

- ^ a b c Conference for a United Front Against Fascism. KPIX-TV. July 19, 1969 – via Bay Area Television Archive.

- ^ a b c d Bloom & Martin 2013, p. 301.

- ^ Bloom & Martin 2013, p. 302.

- ^ Austin, Curtis J. (2006). Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 97–8. ISBN 9781610754446.

- ^ Austin 2006, p. 249.

External links

edit- Fesperman, William (August 10, 2015). "Young Patriots at the United Front Against Fascism Conference (1969)". Viewpoint. Speech by a Young Patriots Organization activist, introduced by Patrick King.