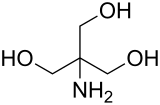

Tris, or tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, or known during medical use as tromethamine or THAM, is an organic compound with the formula (HOCH2)3CNH2. It is extensively used in biochemistry and molecular biology as a component of buffer solutions[2] such as in TAE and TBE buffers, especially for solutions of nucleic acids. It contains a primary amine and thus undergoes the reactions associated with typical amines, e.g., condensations with aldehydes. Tris also complexes with metal ions in solution.[3] In medicine, tromethamine is occasionally used as a drug, given in intensive care for its properties as a buffer for the treatment of severe metabolic acidosis in specific circumstances.[4][5] Some medications are formulated as the "tromethamine salt" including Hemabate (carboprost as trometamol salt), and "ketorolac trometamol".[6] In 2023 a strain of Pseudomonas hunanensis was found to be able to degrade TRIS buffer.[7]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol | |

| Other names

TRIS, Tris, Tris base, Tris buffer, Trizma, Trisamine, THAM, Tromethamine, Trometamol, Tromethane, Trisaminol, Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.969 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H11NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 121.136 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.328g/cm3 |

| Melting point | >175-176 °C (448-449 K) |

| Boiling point | 219 °C (426 °F; 492 K) |

| ~50 g/100 mL (25 °C) | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 8.07 (conjugate acid) |

| Pharmacology | |

| B05BB03 (WHO) B05XX02 (WHO) | |

| Hazards[1] | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Irritant |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H315, H319, H335 | |

| P261, P264, P271, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P332+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Since Tris' pKa is more strongly temperature dependent, its use is not recommended in biochemical applications requiring consistent pH over a range of temperatures. Moreover, the temperature dependance of the pKa (and in turn buffer solution pH) makes pH adjustment difficult.[8] (E.g., the 'room temperature' pH adjustment would not translate to 'measurement conditions' pH, unless care is taken to calculate the effect of temperature, see below.)

Buffering features

editThe conjugate acid of tris has a pKa of 8.07 at 25 °C, which implies that the buffer has an effective pH range between 7.1 and 9.1 (pKa ± 1) at room temperature.

Buffer details

edit- In general, as temperature decreases from 25 °C to 5 °C the pH of a tris buffer will increase an average of 0.03 units per degree. As temperature rises from 25 °C to 37 °C, the pH of a tris buffer will decrease an average of 0.025 units per degree.[9]

- In general, a 10-fold increase in tris buffer concentration will lead to a 0.05 unit increase in pH and vice versa.[9]

- Silver-containing single-junction pH electrodes (e.g., silver chloride electrodes) are incompatible with tris since an Ag-tris precipitate forms which clogs the junction. Double-junction electrodes are resistant to this problem, and non-silver containing electrodes are immune.

Buffer inhibition

editPreparation

editTris is prepared industrially by the exhaustive condensation of nitromethane with formaldehyde under basic conditions (i.e. repeated Henry reactions) to produce the intermediate (HOCH2)3CNO2, which is subsequently hydrogenated to give the final product.[12]

Uses

editThe useful buffer range for tris (pH 7–9) coincides with the physiological pH typical of most living organisms. This, and its low cost, make tris one of the most common buffers in the biology/biochemistry laboratory. Tris is also used as a primary standard to standardize acid solutions for chemical analysis.

Tris is used to increase permeability of cell membranes.[13] It is a component of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine[14] and the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for use in children 5 through 11 years of age.[15]

Medical

editTris (usually known as THAM in this context) is used as alternative to sodium bicarbonate in the treatment of metabolic acidosis.[16][17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Tromethamine". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Gomori, G., Preparation of Buffers for Use in Enzyme Studies. Methods Enzymology., 1, 138-146 (1955).

- ^ a b FISCHER, Beda E.; HARING, Ulrich K.; TRIBOLET, Roger; SIGEL, Helmut (1979). "Metal Ion/Buffer Interactions. Stability of Binary and Ternary Complexes Containing 2-Amino-2(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol (Tris) and Adenosine 5'-Triphosphate (ATP)". European Journal of Biochemistry. 94 (2). Wiley: 523–530. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb12921.x. ISSN 0014-2956. PMID 428398.

- ^ Stanley, David; Tunnicliffe, William (June 2008). "Management of life-threatening asthma in adults". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain. 8 (3): 95–99. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkn012. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Hoste, Eric A.; Colpaert, Kirsten; Vanholder, Raymond C.; Lameire, Norbert H.; De Waele, Jan J.; Blot, Stijn I.; Colardyn, Francis A. (May 2005). "Sodium bicarbonate versus THAM in ICU patients with mild metabolic acidosis". Journal of Nephrology. 18 (3): 303–307. ISSN 1121-8428. PMID 16013019.

- ^ BNF 73 March-September 2017. British Medical Association,, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London. 21 March 2017. ISBN 978-0857112767. OCLC 988086079.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Holert, Johannes; Borker, Aron; Nübel, Laura Lucia; Daniel, Rolf; Poehlein, Anja; Philipp, Bodo (8 January 2024). "Bacteria use a catabolic patchwork pathway of apparently recent origin for degradation of the synthetic buffer compound TRIS". The ISME Journal. 18 (1): wrad023. doi:10.1093/ismejo/wrad023. ISSN 1751-7362.

- ^ Stoll, Vincent S.; Blanchard, John S. (1 January 1990). "[4] Buffers: Principles and practice". Methods in Enzymology. 182: 24–38. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(90)82006-N.

- ^ a b "Sigma tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane; Tris Technical Bulletin No. 106B" (PDF). Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Desmarais, WT; et al. (2002). "The 1.20 Å resolution crystal structure of the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica complexed with tris: A tale of buffer inhibition". Structure. 10 (8): 1063–1072. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00810-9. PMID 12176384.

- ^ Ghalanbor, Z; et al. (2008). "Binding of tris to Bacillus licheniformis alpha-amylase can affect its starch hydrolysis activity". Protein Pept. Lett. 15 (2): 212–214. doi:10.2174/092986608783489616. PMID 18289113.

- ^ Markofsky, Sheldon, B. (15 October 2011). "Nitro Compounds, Aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Vol. 24. p. 296. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_401.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Irvin, R.T.; MacAlister, T.J.; Costerton, J.W. (1981). "Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane Buffer Modification of Escherichia coli Outer Membrane Permeability". J. Bacteriol. 145 (3): 1397–1403. doi:10.1128/JB.145.3.1397-1403.1981. PMC 217144. PMID 7009585.

- ^ Factsheet modernatx.com

- ^ Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting October 26, 2021 fda.gov

- ^ Kallet, RH; Jasmer RM; Luce JM; et al. (2000). "The treatment of acidosis in acute lung injury with tris-hydroxymethyl aminomethane (THAM)". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 161 (4): 1149–1153. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9906031. PMID 10764304.

- ^ Hoste, EA; Colpaert, K; Vanholder, RC; Lameire, NH; De Waele, JJ; Blot, SI; Colardyn, FA (2005). "Sodium bicarbonate versus THAM in ICU patients with mild metabolic acidosis". Journal of Nephrology. 18 (3): 303–7. PMID 16013019.