Tridacna derasa, the southern giant clam or smooth giant clam, is a species of extremely large marine clam in the family Cardiidae.

| Tridacna derasa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Cardiida |

| Family: | Cardiidae |

| Genus: | Tridacna |

| Species: | T. derasa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tridacna derasa | |

Description

editThe southern giant clam is one of the largest of the "giant clams", reaching up to 60 cm in length.[4] The species is also known as the smooth giant clam because of the relative lack of ribbing and scales on its thick shell. The smoothness of the southern giant clam's shell and its six to seven vertical folds help to distinguish it from its larger relative, Tridacna gigas, which has four to five folds and a rougher texture. Lack of scutes (scale-like protrusions of the shell) that are present in most other Tridacna species is a defining characteristic of this species, although in aquacultures specimens have been observed to develop scutes in at least one abnormal case.[5] The mantle usually has a pattern of wavy stripes or spots, and may be various mixtures of orange, yellow, black and white, often with brilliant blue or green lines.[6][unreliable source?] Derasa produce the color white in their mantle using multi-colored crystalline pigment cells, while T. maxima cluster red, blue and green cells.[7]

Distribution and habitat

editThe southern giant clam is native to waters around Australia, Cocos Islands, Fiji, Indonesia, New Caledonia, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vietnam.[8] Populations have also been introduced to American Samoa, Cook Islands, Marshall Islands and Samoa, and reintroduced after extinction in Guam, the Federated States of Micronesia and Northern Mariana Islands.[4] The southern giant clam is found on the outer edges of reefs at depths of 4 to 10 meters.[6]

Biology

editThe Tridacna clam has muscles for opening and closing its shell and a foot for attaching to reef substrate. It respires through gills and feeds through a mouth.[9][unreliable source?] Most clams fulfill their nutritional requirements by filter feeding and absorbing dissolved organic compounds from the water, but Tridacna clams have gone further than this by using photosymbiotic algae, zooxanthellae, in their tissues to provide food for them.[9][10][unreliable source?] Through photosynthesis the zooxanthellae transform carbon dioxide and dissolved nitrogen, such as ammonium, into carbohydrates and other nutrients for their hosts.[10][11]

When Tridacna clams first attain sexual maturity they are male, but about a year later become hermaphrodites, possessing both male and female reproductive organs. However, the release of sperm and eggs are separate in order to prevent self-fertilisation, although self-fertilisation can occur. The breeding season of the southern giant clam usually occurs in spring and summer, although they may be induced to spawn through the year.[10][12]

Conservation

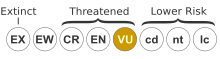

editThe southern giant clam is classified as Vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List,[1] and is listed on Appendix II of CITES.[13] The southern giant clam is a popular food item and aquarium species, and has therefore been hunted extensively throughout its natural habitat.[6] However, specimens traded today tend to be the result of aquaculture farms rather than wild-caught individuals, because the southern giant clam was one of the first clams to be bred commercially.[6] This occurred at the MMDC Giant Clam Hatchery in Palau, which focused on Tridacna derasa in pioneering large-scale developments.[14]

References

edit- ^ a b Wells, S. (1996). "Tridacna derasa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T22136A9362077. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T22136A9362077.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Bouchet, P.; Rosenberg, G.; ter Poorten, J. (2013). "Tridacna derasa (Röding, 1798)". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ a b CITES: Twenty-second Meeting of the Animals Committee Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Lima (Peru), 7–13 July 2006 (January 2007).

- ^ Adams, Jake (6 August 2010). "Batch of scaly Derasa clams spotted, what does it mean?". reefbuilders.com. Reef Builders, Inc. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d Lukan, E. M. (1999). Critter Corner: Tridacna derasa. Fish 'N' Chips: A Monthly Marine Newsletter, 1999.

- ^ "Giant clams could inspire better color displays and solar cells". www.gizmag.com. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Lucas & Copland (1988). Giant Clams in Asia and the Pacific. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. p. 23. ISBN 0-949511-70-6.

- ^ a b Tridacna Clams in the Reef Aquarium (January 2007).

- ^ a b c Lukan, E. M. (1999). Critter Corner: Tridacnid Clams: The Basics. Fish 'N' Chips: A Monthly Marine Newsletter, 1999.

- ^ Lucas, J. (June 1994). "Biology, exploitation, and mariculture of giant clams". Reviews in Fisheries Science. 2 (3): 188–194. doi:10.1080/10641269409388557.

- ^ Lucas, J. (June 1994). "Biology, exploitation, and aquaculture of giant clams". Reviews in Fisheries Science. 2 (3): 184–188. doi:10.1080/10641269409388557.

- ^ CITES (January 2007).

- ^ Heslinga; Watson & Isamu (1990). Giant Clam Farming. Honolulu, Hawaii: Pacific Fisheries Development Foundation. pp. 1–179 + appendices.

External links

edit- Photos of Tridacna derasa on Sealife Collection

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "Tridacna derasa" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.