Myōgon-ji (妙厳寺), also known as Toyokawa Inari (shinjitai: 豊川稲荷; kyūjitai: 豐川稲荷), is a Sōtō Zen Buddhist temple located in the city of Toyokawa in eastern Aichi Prefecture, Japan.

| Enpuku-zan Toyokawa-kaku Myōgon-ji (Toyokawa Inari) | |

|---|---|

円福山 豊川閣 妙厳寺 (豊川稲荷) | |

Toyokawa Inari's main hall (honden) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Buddhism |

| Sect | Sōtō |

| Deity | Senju Kannon (honzon) Toyokawa Dakini Shinten |

| Location | |

| Location | 1 Toyokawa-chō, Toyokawa, Aichi Prefecture |

| Country | Japan |

| Geographic coordinates | 34°49′28.26″N 137°23′31.24″E / 34.8245167°N 137.3920111°E |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | Tōkai Gieki |

| Completed | 1441 |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Although the temple's main image is that of the thousand-armed form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Senju Kannon), it is more well-known for its guardian deity Toyokawa Dakini Shinten, a syncretic goddess who assumed characteristics of Inari, the Shinto kami of fertility, rice, agriculture, industry and worldly success. Despite the presence of a torii gate at the entrance (a relic of the amalgamation of Buddhism and native beliefs before the early modern period), the institution is a Buddhist temple and has no overt association with the Shinto religion.

Background

editDakiniten is a Japanese Buddhist deity who originated from the ḍākinī, a type of female spirit in Hinduism and Buddhism. Said in Buddhist belief to have once been a race of malevolent demonesses who preyed on humans, they were eventually subjugated by the buddha Vairocana, who took the form of the wrathful deity Mahākāla (Daikokuten in Japanese) to wean them away from their human-eating habits and lead them to the Buddhist path.[1][2][3]

In contrast to Nepalese and Tibetan Buddhism, where 'ḍākinī' eventually came to denote female personifications of enlightenment (e.g. Vajrayoginī) or to human women with a certain amount of spiritual development, ḍākinīs were regarded as members of the retinue of the god Yama (the judge of the dead) upon their introduction to Japan via the esoteric Shingon and Tendai schools before they were eventually coalesced into a single goddess called 'Dakiniten', who gradually developed an independent cult of her own from the end of the Heian period onwards. The ḍākinīs were associated with scavengers such as jackals and foxes, which led to Dakiniten becoming syncretized with the Shinto agricultural kami Inari (as foxes were seen as the messengers of this deity) and her gaining certain traits of the latter.[4] Indeed, Dakiniten's cult and that of Inari became inextricably fused by the medieval period that the name 'Inari' was even popularly applied to places of Dakiniten worship.[5]

Although Dakiniten was commonly depicted as a woman riding a white fox, bearing a sword in one hand and a wish-granting jewel (cintāmaṇi) on the other,[6] the Dakiniten of Toyokawa Inari is shown bearing bundles of rice stalks on a carrying-pole over her right shoulder instead of a sword.[7]

History

editMyōgon-ji was founded in 1441 by the Buddhist priest Tōkai Gieki (東海義易, 1412–1497), a sixth generation disciple of Kangan Giin, who was a disciple of Dōgen, the founder of the Japanese Sōtō school.

In 1264, Giin traveled to Song China in order to present Dōgen's recorded sayings, the Eihei Kōroku, to monks in the Caodong lineage of Dōgen's teacher Tiantong Rujing.[8] Legend claims that as Giin was about to leave China in 1267, he experienced a vision of a goddess riding on a white fox, bearing a jewel on one hand and a shoulder pole laden with sheaves of rice on the other. The goddess identified herself as Dakiniten and vowed to become Giin's protector. Upon his return to Japan, Giin made a statue of Dakiniten based on this vision, which eventually ended up years later in Gieki's possession. Gieki enshrined both it and an image of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Kannon) at the temple he established, designating Dakiniten as the guardian (chinju) of the temple complex. Since then, the goddess was widely revered as a patron against calamity and a bringer of relief and prosperity.[9][10]

The temple was patronized in the Sengoku period by Imagawa Yoshimoto, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, and by pilgrims from the merchant classes in the Edo period through the modern period.[9] Other notable devotees of Toyokawa Dakiniten include the Edo period magistrate and daimyō Ōoka Tadasuke, whose residence in Akasaka, Tokyo eventually became Toyokawa Inari's Tokyo branch temple, the painter Watanabe Kazan, and Prince Arisugawa Taruhito, who donated a framed sign (扁額, hengaku) in his own calligraphy of the words "Toyokawa Temple" (kyūjitai: 豐川閣, Toyokawa-kaku; shinjitai: 豊川閣).[9]

The Toyokawa Mantra

editTradition claims that Dakiniten taught Kangan Giin the mantra On shira batta niri un sowaka (唵尸羅婆陀尼黎吽娑婆訶, reconstructed as Oṃ śila bheda nirṛti huṃ svāhā[11]), which is traditionally explained as meaning: "When this spell is chanted, the faith in me reaches everywhere, and by the true power of the Buddhist precepts (śila), evil and misfortune will be abolished and luck and wisdom attained; suffering removed and comfort achieved, and pain transformed into delight."[9][10] Another possible interpretation is: "I vow to destroy (bheda) all my sufferings (nirṛti?) and overcome temptations with the power of monastic discipline (śila)."[11]

This mantra features prominently in services conducted in the temple and in Toyokawa Dakiniten worship in general.

Tōkai Gieki and Heihachirō

editThe temple was also known as 'Heihachirō Inari' (平八郎稲荷) due to a story involving its founder Tōkai Gieki.

It is said that when Gieki had was about to establish what would become Myōgon-ji, an old man carrying a small pot or cauldron (kama) appeared before him and offered his services. The old man went on to work at Gieki's temple, using his pot to cook meals for the monks. To the surprise of many, the pot was seemingly magical, in that it continually provided an endless supply of food enough to satisfy tens and even hundreds of people. When asked how he was capable of performing such miraculous feats, the man replied that he had three hundred and one servants at his bidding. The old man stayed by Gieki's side until the latter's death, at which he vanished without a trace, leaving only his pot behind. People then came to revere the old man, dubbed 'Heihachirō' (平八郎), as a servant or avatar of Dakiniten, a fox spirit (kitsune) who assumed human form.[10]

Cultural Properties

editMost of the temple was rebuilt in the Meiji period or later; however, the Sanmon dates from 1536 and is the oldest existent building in the complex. The Main Hall was reconstructed in the Tempo period (1830-1843), and several other buildings also date from the Edo period. In terms of registered cultural properties, the temple has a wooden Kamakura period statue of Jizō Bosatsu which is a National Important Cultural Property.

Tōkai Hundred Kannon

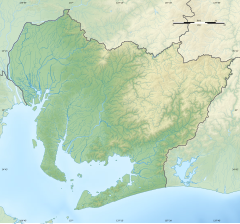

editThe Toyokawa Inari combines with the Mino Thirty-three Kannon in Gifu Prefecture, the Owari Thirty-three Kannon in western Aichi Prefecture, and the Mikawa Thirty-three Kannon (三河三十三観音) in eastern Aichi Prefecture to form a pilgrimage route known as the Tōkai Hundred Kannon.[12]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Faure, Bernard (2015). The Fluid Pantheon: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. p. 195.

- ^ Faure, Bernard (2015). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 117–118.

- ^ "荼枳尼天 (Dakiniten)". Flying Deity Tobifudō (Ryūkō-zan Shōbō-in Official Website). Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ Faure, Bernard (2015). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 119–121.

- ^ Faure, Bernard (2015). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 121–123.

- ^ "Dakiniten, the Buddhist Manifestation of the Shinto Deity Inari". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Faure, Bernard (2015). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 124–131.

- ^ Eihei Dōgen (2010). Leighton, Taigen Dan (ed.). Dogen's Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Koroku. Translated by Taigen Dan Leighton & Shohaku Okumura. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-8617-1670-8.

- ^ a b c d "Guide to Toyokawa Inari" (PDF). Toyokawa Inari Official Website. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ a b c "当山の歴史". Toyokawa Inari Official Website. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ a b Chaudhuri, Saroj Kumar (2003). Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan. Vedams eBooks (P) Ltd. p. 161. ISBN 978-8-1793-6009-5.

- ^ Owari Thirty-three Kannon Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. Aruku88.net. Accessed May 4, 2009.

Bibliography

edit- Faure, Bernard (2015a). The Fluid Pantheon: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5702-8.

- Faure, Bernard (2015b). Protectors and Predators: Gods of Medieval Japan, Volume 2. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5772-1.

- Smyers, Karen Ann. The fox and the jewel: shared and private meanings in contemporary Japanese. University of Hawaii Press (1998). ISBN 0-8248-2102-5