Torture of slaves in the United States was fairly common, as part of what many slavers claimed was necessary discipline. As one history put it, "Stinted allowance, imprisonment, and whipping were the usual methods of punishment; incorrigibles were sometimes 'ironed' or sold."[1]

Whips and similar

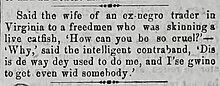

editAccounts of torture come from both slavers and the enslaved, although accounts from the formerly enslaved were historically mistrusted or discounted. In one famous such case, retold in a reconsideration of the WPA Slave Narratives by historian Rebecca Onion, "In Virginia, Eudora Ramsay Richardson, the state director, refused to believe a story that Roscoe Lewis, the director of that state's Negro Writers Unit (and a professor at the Hampton Institute), recorded during an interview with ex-slave Henrietta King. King told Lewis that she had taken some candy at age eight or nine, and that her slaveholder had punished her by holding her head under a rocking chair while she whipped her. The incident had resulted in a crushed jawbone and permanent disfigurement. (King said the violence gave her 'a false face...What chilluns laugh at an' babies gits to cryin' at when dey sees me.') Disbelieving Lewis's account, Richardson went to King's home to fact-check it, thinking it was a 'gross exaggeration'. She found instead that '[King] looks exactly as Mr. Lewis describes her and she told me, almost word for word the story that Mr. Lewis relates.'"[2]

A slave owner named B. T. E. Mabry of Beatie's Bluff, Madison County, Mississippi placed a runaway slave ad in 1848 that described the missing man as "has been severely whipped, which has left large raised scars or whelks in the small of his back and on his abdomen nearly as large as a persons finger".[3] In the testimony of Peter of the scourged back he mentions "salt brine, which Overseer put in my back".[4] This practice, sometimes called salting, was attested in many accounts of slave torture reported over many decades.[5] Other substances, including turpentine, hot-pepper juice, and dripping candle wax, were also used.[6][7] An interview with Andrew Boone for the WPA's Slave Narrative Collection in the 1930 matter-of-factly described the practice: "By dis time de blood sometimes would be runnin' down dere heels. Den de next thing was a wash in salt water strong enough to hold up an egg. Slaves wus punished dat way fer runnin' away an' sich."[5] Another account stated, "...there was a puddle of blood on the floor just as if a hog had been killed. He then took a paddle and paddled her on top of that almost to death, and made me wash her down with brine. The brine is to keep the raw flesh from putrifying, and to make it heal quick. They mix it very thick and rub it in with corn husks."[8]

There was a form of whipping called hand sawing: "Jones figured that 'hand-sawing' probably meant 'a beating administered with the toothed-edge of a saw'."[9] In November 1838, J. R. Long reported that a slave who had run away from his plantation had been caught. He added: "I gave him a real whipping and hand sawing and he has been a fine negroe ever since. I told him he might run off if he chosed and I would knock out one of his jaw teeth and brand him and I intend to stick to my promise."[10]

Historian Charles S. Sydnor reported that "Paul, the headwaiter of the hotel" in Grenada, Mississippi was accused of helping slaves escape north (most likely by the town's two railroad connections); after whipping him with rawhide failed to elicit a confession, his accusers escalated to something called "the hot paddle," which was "a thin piece of wood with holes bored through it, and it was applied to the naked flesh." According to Sydnor, Paul never confessed.[11]

In addition to whipping by owners and overseers, at least two slave traders are said to have engaged in systematic torture, reserving flogging rooms in their slave jails for this purpose: Theophilus Freeman of New Orleans, and the slavers of Poindexter & Little, where the lashes were administered by "Uncle Billy." Public jails that used corporal punishment on slaves included the Charleston Workhouse, Louisville Workhouse, and the Cage in Richmond, Virginia.[12]

Restraints

editAmerican slaves were commonly chained and restrained by various means. One account of a journey down the Mississippi River states, "...a little below the red Church, at the house of a planter, whose negroes and some from the neighbouring plantations, were forgetting their sorrows in the festivity of a dance—among the merriest of them was one who had an iron collar round his neck, with two small bars projecting as high as the top of his head, one on each side, and a chain passing from the collar down each side to his knees by which he was secured to staples in the floor at night—He had attempted to run away—Some of the negroes showed me several irons of different forms, in which delinquents are confined—."[14]: 391 Further down the River at New Orleans: "The streets are wide, and cross each other at right angles. They are cleaned by negroes (runaways) all of whom are chained, that is, have chains to their legs, which are fastened round their middle during the day, and secured to rings in the floor of the calaboose or prison at night."[14]: 391

A fugitive slave named John or Jack was put in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi jail in 1850; when he was captured he had an iron collar with bell attached.[15] The Bullock Museum in Texas holds a belled slave collar.[16] Mary Gaffney, interviewed for the WPA Slave Narratives Project, told the interviewer that "back there in Mississippi I'se saw slaves wear bells because they would get a pass and not come home when Maser would tell them to and for being contrary. Them bells was fixes on a brace so'es the slave could not hold the clapper or get them off."[17] The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan holds a hooked collar used on slaves; "Slaves known for running away might have had to wear an iron collar like this, for punishment or to prevent them from running away again. The hooks caught on bushes or tree limbs, causing a violent jerking to the individual's head and neck."[18]

In 1820 a 21-year-old man named William was picked up by the Wilkinson County jailor "with a large iron on his right leg, and a trace chain around his neck, locked on with a padlock."[19] In 1834, a runaway slave, named Henry (Hal for short) was picked up in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, at which time he "had on his wrists a pair of negro traders' hand cuffs broken."[20] Lamb was wearing a leg iron when he escaped a plantation near Pinckneyville, Mississippi in 1818.[21] A runaway slave ad placed in a New Orleans newspaper in 1839 mentioned that the missing man, "WILLIAM, or BILL, a cook by trade...had a chain to his leg when he left the City Hotel, Common Street."[22]

In Slave Life in Georgia John Brown described accompanying Bob Freeman when he took prisoners from Theophilus Freeman's jail to the blacksmith to have shackles put on and removed.[23] A plantation record book from Georgia records the fees charged by the blacksmith for this service: "May, 1852, Taking off Irons from Negro, $2.00; Ironing a Negro, $3.50".[24] According to a slave testimony published in The Emancipator, "It is very common for slaves to run away into the woods after being badly whipped. They are forced to, for they cannot do their tasks, and so they have to stay in the woods till they get well. Sometimes they stay there five or six weeks till they are taken, or are driven back by hunger. I have known a great many who never came back; they were whipped so bad they never got well, but died in the woods, and their bodies have been found by people hunting. White men come in sometimes with collars and chains and bells, which they had taken from dead slaves. They just take off their irons and then leave them, and think no more about them."[8]

Mutiliation and branding

editAccording to historian Michael Tadman, "Persistently troublesome slaves were often to be identified by whip marks, while reclaimed runaways were often identifiable by brandings, by cropped ears, or by the absence of front teeth."[26]

There is widespread evidence that branding irons were used on people. In 1806, Benjamin Farrar, "one of the most prosperous planters" of the Natchez District,[27] offered a $20 reward for the capture of 26-year-old Sam, "5 feet 9 or 10 inches high, large prominent eyes, he has an impediment in his speech, is branded on the breast B. F."[28] George C. Purvis of Mount Pleasant explained in a runaway slave ads of 1819 and 1820 that Harry—who sometimes called himself Free Jim—had been branded with Purvis' initials G. P. because Harry was a "noted runaway."[29][30] A man named Willis who had recently been transported by slave traders from Tennessee to Natchez "was branded in the hand for theft" on May 2 or 3, 1820 "and on the 6th made his escape."[31] In 1832, a Mississippi county sheriff described a fugitive slave in his jail as "branded on the forehead with something like LB".[32] A man named Frank was branded on both cheeks "which is plain to be seen when said negro is newly shaved".[33] News reports of 1847 had it that an Englishman living at Cape Girardeau had branded a man named Reuben on the face with the words "A slave for life".[34][35] In 1852, a planter living near New Carthage, Louisiana was looking for a 30-year-old man named Henry Owen, a runaway slave who could be readily identified if captured, as he had been branded with his previous owner's initials and had his current owner's name written "across his breast in India ink."[36] The January 12, 1856 issue of The Creole newspaper of Louisiana reported on a jury's conviction of "slave owner William Bell for branding a runaway slave he had repossessed. He was fined $200 and 'the jury decreed the slave should be sold away from him.'"[37]

Strategic amputation and mutilation of slaves by slave owners was also known. Harriet Beecher Stowe described an escaped preacher who had been branded on both breasts and had toes cut off on both feet.[38] A runaway slave ad published in Huntsville, Alabama in 1849 described 30-year-old Ben of Martin County, North Carolina as having "no particular marks perceptible, only the little toe of each foot is off."[39] A black man arrested in Alabama in 1839 had "a small piece out of each of his ears."[40]

Sexual abuse

editSexual cruelty is documented: The 1853 case of Humphreys vs. Utz in the Louisiana Supreme Court awarded civil damages to a Madison Parish plantation owner whose overseer nailed a man's penis to a bedstead and then whipped him until he ripped his penis off the nail. The man, who was called Ginger Pop or Bob, was about 30 years old. He died shortly thereafter and was buried on the grounds of the plantation.[41] In June 1863, New York Times correspondent "De Soto" (William George)[42] reported witness statements describing genital burning and breast mutilation on a Black River plantation in Catahoula Parish, concluding his account "If any one, upon reading this...says he does not believe it, I have only to reply, I do."[43]

Methods of execution

editJames Robinson, a Protestant minister and a veteran of both the American Revolution and the War of 1812, described a capital punishment on the Mississippi River plantation of Calvin Smith. A slave called Ben killed overseer Bird Carter. A cylindrical casket was made "just his length" and spiked through with sharpened nails. Ben was taken to the top of a hill, put inside the casket, and "was rolled down to the bottom. Of course his whole body was a perfect jelly, or perfect mince meat. Every particle of flesh was torn from his bones. The cask was opened, and the jelly, for his flesh was nothing else, was thrown into the river."[44] This device appears to be described in at least one other slave narrative: "He had a neighbor named Bellinger, on the Dorchester road. One day master sent me to his plantation on an errand, and I saw a man rolling another all over the yard in a barrel, something like a rice cask, through which he had driven shingle nails. It was made on purpose to roll slaves in. He was sitting on a block, laughing to hear the man's cries. The one who was rolling wanted to stop, but he told him if he did'nt roll him well he would give him a hundred lashes. Bellinger is dead now."[8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Flanders (1933), p. 149.

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (July 6, 2016). "Is the Greatest Collection of Slave Narratives Tainted by the Racism of Its Collectors?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "$20 Reward". The Weekly Mississippian. May 5, 1848. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-06-24.

- ^ Bostonian (December 3, 1863) [1863-11-12]. "The Realities of Slavery: To the Editor of the N.Y. Tribune". New-York Tribune. p. 4. ISSN 2158-2661. Retrieved 2023-07-27 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Dickman, Michael (2015). Honor, Control, and Powerlessness: Plantation Whipping in the Antebellum South (Thesis). Boston College. hdl:2345/bc-ir:104219.

- ^ Sebesta, Edward H. (November 26, 2016). "Robert E. Lee Park: Robert E. Lee Has His Slaves Whipped and Brine Poured Into the Wounds". Robert E. Lee Park. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ^ Weld, Theodore (1839). "Floggings". American Slavery As It Is. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society. p. 63. Retrieved 2023-07-28 – via utc.iath.virginia.edu.

- ^ a b c "A Runaway Slave. Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave". docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved 2024-10-05.

- ^ Gutman, Herbert G. (1975). Fogel, Robert William; Engerman, Stanley L. (eds.). "Enslaved Afro-Americans and the "Protestant Work Ethic"". The Journal of Negro History. 60 (1): 65–93. doi:10.2307/2716796. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2716796. S2CID 150340537.

- ^ Tadman, Michael (November 1977). Speculators and Slaves in the Old South: A Study of the American Domestic Slave Trade, 1820-1860 (PDF). University of Hull (Thesis). p. 159. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ Sydnor, Charles S. (Charles Sackett). Slavery in Mississippi. State Library of Pennsylvania. D. Appleton-Century Co.

- ^ Dabney, Virginius (1990) [1976]. Richmond: The Story of a City (Rev. ed.). University of Virginia Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8139-3430-3.

- ^ Genius of Universal Emancipation. B. Lundy. June 1830.

- ^ a b Teas, Edward; Ideson, Julia; Higginbotham, Sanford W. (1941). "A Trading Trip to Natchez and New Orleans, 1822: Diary of Thomas S. Teas". The Journal of Southern History. 7 (3): 378–399. doi:10.2307/2191528. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2191528.

- ^ "Slave record". Natchez Daily Courier. November 26, 1850. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- ^ "Slave collar with bells". Bullock Texas State History Museum. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- ^ Rawick, George P. (1979). The American Slave: Texas narratives. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-21423-3.

- ^ "Slave Collar, circa 1860 - The Henry Ford". www.thehenryford.org. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- ^ "Notice". Mississippi Free Trader. October 17, 1820. p. 1. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "Committed to the Jail of Rutherford county". The Weekly Monitor. January 18, 1834. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ "Forty Dollars Reward". Natchez Gazette. July 18, 1818. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-07-14.

- ^ "25 Dollars Reward". The Times-Picayune. April 19, 1839. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- ^ Brown, John (1855). Slave Life in Georgia: A Narrative of the Life, Sufferings, and Escape of John Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Now in England. Xerox University Microfilms. p. 121.

- ^ Flanders (1933), p. 117.

- ^ Bitikofer, Sheritta (July 15, 2021). "Untangling the Marmillions, Part 1". Emerging Civil War. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ Tadman, Michael (November 1977). Speculators and Slaves in the Old South: A Study of the American Domestic Slave Trade, 1820-1860 (PDF). University of Hull (Thesis). Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ Pinnen, Christian, "Slavery and Empire: The Development of Slavery in the Natchez District, 1720-1820" (2012). Dissertations. 821. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/821

- ^ "TWENTY DOLLARS REWARD". The Mississippi Messenger. February 3, 1806. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-09-10.

- ^ "fifty dollars reward". Natchez Gazette. May 27, 1820. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-08-17.

- ^ "Fifty Dollars Ranaway or Stolen". Natchez Gazette. July 24, 1819. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-08-17.

- ^ "Willis - branded - John Farney of Tennessee". Natchez Gazette. May 27, 1820. p. 2. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ "Southern Planter 13 Oct 1832, page 4". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ McDougle, Ivan E. (1918). "Slavery in Kentucky: The Development of Slavery". The Journal of Negro History. 3 (3): 214–239 (223, branding). doi:10.2307/2713409. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2713409. S2CID 149804505.

- ^ "St. Louis". The Vermont Patriot and State Gazette. February 25, 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Cape Girardeau". The Liberator. September 3, 1847. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Twenty-Five Dollars Reward". Vicksburg Whig. January 14, 1852. p. 3. Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ^ "A good inheritance; a genealogical record of ten generations of descendants of John Harmon of Scarboro, Maine ... Compiled and edited by Francis Stuart ..." HathiTrust. p. 33. hdl:2027/wu.89062402920. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1853). A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co. p. 429. LCCN 02004230. OCLC 317690900. OL 21879838M.

- ^ "Committed". The Democrat. September 19, 1849. p. 4. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ "Ranaway". Cahawba Democrat. June 29, 1839. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Schafer, Judith (June 1, 1993). "Sexual Cruelty to Slaves: The Unreported Case of Humphreys v. Utz - Symposium on the Law of Slavery: Criminal and Civil Law of Slavery". Chicago-Kent Law Review. 68 (3): 1313. ISSN 0009-3599.

- ^ Smith, Myron J. Jr. (April 26, 2017). Joseph Brown and His Civil War Ironclads: The USS Chillicothe, Indianola and Tuscumbia. McFarland. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-4766-2680-2.

- ^ De Soto (June 14, 1863). "Horrors of the Prison-House". The New York Times. Vol. XII, no. 3657. "De Soto" was pen name of war correspondent William George. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The narrative of James Roberts, soldier in the revolutionary war and at the battle of New Orleans. Chicago: printed for the author, 1858". HathiTrust. p. 25. hdl:2027/mdp.39015012058742. Retrieved 2024-07-14.