Thomas Taylor, Baron Taylor of Blackburn, CBE, JP, DL[1][2][3] (10 June 1929 – 25 November 2016) was a businessman and Labour politician. He was a member of Blackburn Council for 22 years, serving as its leader from 1972 to 1976. In 1978, he became a member of the House of Lords. In 2009, he was suspended from the House, along with Baron Truscott, as a result of the cash for influence scandal, the first peers to be suspended since the 17th century.

The Lord Taylor of Blackburn | |

|---|---|

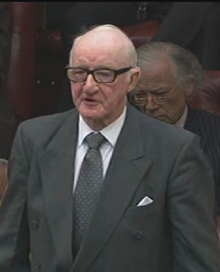

June 2013, asking a question about badger culling | |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 4 May 1978 – 25 November 2016 Life Peerage | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Taylor 10 June 1929 |

| Died | 25 November 2016 (aged 87) |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse | Kathleen |

| Children | 1 son |

Early life and family

editThomas Taylor was born in Blackburn, the son of James and Edith Taylor. He attended Blakey Moor elementary school, but left at the age of fourteen to work as a shop assistant in the local co-op. He later became a branch representative of the USDAW union.

In 1950, at the age of 21, Taylor married Kathleen Nurton. They had one son, Paul Taylor.

Career

editTaylor was elected to Blackburn Town Council in 1954, later becoming chairman of the education committee. In 1960, he was appointed a JP on the Blackburn bench. A Congregationalist and committed Christian, he was named president of the Free Church Council in 1963.[4] He was awarded the Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1969 Queen's Birthday Honours list.[5] He served as leader of Blackburn Council from 1972 to 1976, on the recommendation of fellow church-goer and former leader Sir George Eddie. For his services to local government, he was awarded the Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1974 Queen's Birthday Honours.[6]

One of Taylor's successes as a councillor was the setting up of special centers to help recent immigrants who had arrived in the town to work in the textile industry. As chairman of the education committee, he imposed a ceiling of 7% on the number of immigrant children in any one school, bussing additional children to other schools. The aim was to ensure an ethnic mix in local schools to promote social integration and help the children learn English.[7]

He became leader of education services on Lancashire County Council, as well as being Chairman of the juvenile bench. A consensual politician in the tradition of Hugh Gaitskell, he steered comprehensive education through despite some concerns in the town. There he developed the Rochdale tradition of co-operative societies on the council bringing together teachers and parents on a corporatist model. He utilized the leverage of businesses to help finance educational needs by brokerage of a third way for community uses of premises out of school hours and during holidays.[8] He was not a particular friend of Barbara Castle, the local MP who was so close to Prime Minister Harold Wilson, and was delighted to influence the succession of Jack Straw to the seat on her retirement. Taylor's socialist circle included James Callaghan; when Taylor lost his seat on the Blackburn Council in 1976 he was a natural recruit for the labour peerage.[7] His froideur toward Castle was not helped when he was asked to share an office at the House of Lords.

National education and Labour governments

editTaylor was an acolyte of Harold Wilson. Sitting on the Public School Commission in 1958, he attacked Public Schools Headmasters Conference reluctance to relinquish their independent status. Their refusal to integrate in the comprehensive system caused Labour and Taylor to threaten class warfare for failing to modernize. In 1972, Taylor was embroiled in a row to dismiss a communist English lecturer, Dr. David Craig, at the new Lancaster University of which he was a co-founder and deputy Pro-Chancellor.[8] Students staged a sit-in when the Vice-Chancellor refused to lift a threat of disciplinary action against the political agitation. Taylor was remitted to act independently but investigate the causes. Taylor's Report of July 1972 exonerated the local authority of any blame, but thought the whole case had poisoned the atmosphere and culture of the university. Craig was reinstated, though outside the faculty, while the Vice-Chancellor archly refused any assistance for delegations. The following year he accused the Conservative government of a failure to invest: a creaking management had invested the system with paralysis by analysis.

In his role as president of the Association of Education Committees, Taylor continued to press for more investment in schools and universities. A somewhat cynical approach was dictated by his disdain for the peerage, "or as third best chose a mother who has a degree." He carried forward the tripartite industrial strategies of Labour's super-ministries into the new Wilsonian era, when the Education Secretary Reg Prentice asked him to report on school management. The report New Partnership for Our Schools was the first attempt to put schools on the same footing as independents by giving overall management control to a board of Governors, in co-operation with the teachers and parents.[8][9]

Taylor was Chairman of the Electricity Consultative Council for the Northwest and a member of the Board of Norweb from 1977 to 1980. He served on various governmental bodies connected with education in the region, including the North West Economic Planning Council and the North West Area Health Authority. He was created a Life Peer on 4 May 1978 taking the title Baron Taylor of Blackburn, of Blackburn in the County of Lancashire.[10]

He was listed in Who's Who 2009 as a non-executive director of Drax Power Ltd and A Division Holdings, a Consultant to BAE Systems plc; Initial Electronic Security Systems Ltd; and an adviser to Electronic Data Systems Ltd, AES Electric Ltd, United Utilities plc, Experian, and Capgemini UK plc.[9] On 29 January 2009, Experian agreed with Taylor that he would retire as an adviser.[11] By 30 January 2009, he was an adviser to NPL Estates, Alcatel-Lucent, Canatxx Energy Ventures Ltd, BT plc, Gersphere UK and T-Systems; and a non-executive director only of A Division Holdings [12]

He was president or patron of various organizations and held an Hon. LLD from the University of Lancaster from 1996. He was a Freeman of Blackburn and the City of London.[13] At various times in his career, he was also chairman of the National Foundation for Visual Aids.

Health

editLabour was in opposition in 1983, and Taylor was alleged to have been a likely appointment to the front bench, but his wife committed him to hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983, due to a problem with alcohol. Taylor applied for a writ of habeas corpus arguing that the Mental Health Act could not apply to peers when the House was sitting. After 19 days in hospital, his barrister secured his release, and the case never came to court.[7]

2009 cash for influence scandal

editIn late-January 2009, Taylor was one of four Labour peers accused of 'sleaze' by The Sunday Times — it was alleged that Taylor proclaimed to two journalists posing as lobbyists that he was ready, willing, and able to help a business secure favorable legislation in their sphere of interest in return for a fee reported to be in excess of £100,000.[14] Taylor was duped, and his behavior exposed by the reporter's 'sting' operation. The Conservative leader in Blackburn with Darwen demanded that the Freedom of the City Award be stripped from the former councillor.[15] A few days later on 20 May 2009, the House of Lords considered the report of its Privileges Committee[16] and voted to suspend Taylor and Peter Truscott for six months, the first such action since the 17th century.[17]

Expenses

editIn 2005, Taylor claimed £57,000, the second-highest level of expenses claimed in the House of Lords. He spoke 15 times in the chamber that year.[citation needed]

Over the 2014-15 parliamentary session, Taylor claimed £43,110 in expenses, including £29,100 in tax-free attendance allowances, during which he did not speak in the House of Lords.[18] Taylor, then aged 86, defended his record by saying he votes regularly and only speaks on matters of which he has some knowledge or experience.[19]

Death

editOn 17 November 2016, Taylor was involved in an accident when his mobility scooter collided with a van on the corner of Millbank and Great College Street, near the House of Lords. He died on 25 November 2016 as a result of injuries sustained in the crash.[20] Angela Smith, Shadow leader of the House of Lords, said he would be "sadly missed". She continued, "Tom Taylor had a life-long commitment to the Labour Party, through both local government and Parliament, and was held in high regard and with great affection by his party colleagues."[3] The Metropolitan Police investigated the scene and detained a 55-year-old man but had not pressed charges at the time of the baron’s death in hospital.[21] In March 2018, the driver admitted to causing the death by careless driving[22] and was given a 24-week suspended sentence on 9 April 2018.

Arms

edit

|

Footnotes

edit- ^ "Lord Taylor of Blackburn". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Lord Tom Taylor of Blackburn dies after being hit by van". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Lord Taylor dies after mobility scooter crash". BBC News. 25 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Burke's Peerage, 107th ed., vol.III (2003)

- ^ "No. 44863". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 June 1969. p. 5973.

- ^ "No. 46310". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 June 1974. p. 6801.

- ^ a b c Langdon, Julia (29 November 2016). "Lord Taylor of Blackburn obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Taylor of Blackburn, Baron". Who's Who. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ a b "A Division - Our Chairman". A Division Group. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ "No. 47529". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 May 1978. p. 5481.

- ^ Peer at centre of 'cash for legislation' inquiry removed from credit check firm's payroll The Guardian 30-Jan-2009

- ^ Register of Members Interests House of Lords accessed 30-Jan-09

- ^ "Sleaze row peer claims £400,000 just in expenses". Associated Newspapers. 27 January 2009. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ Whispered over tea and cake: price for a peer to fix the law, The Sunday Times, 25 January 2009

- ^ "Calls for Lord Taylor of Blackburn to be sacked". Lancashire Telegraph. 15 May 2009.

- ^ The Committee Office. "House of Lords - The Conduct of Moonie, Snape, Truscott and Taylor of Blackburn - Privileges Committee". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Lords vote to suspend two peers BBC News

- ^ Casalicchio, Emilio (29 May 2016). "Expenses: £621,000 claimed by silent peers in 2014-15". PoliticsHome. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ Jacobs, Bill (7 January 2016). "Lord Taylor defends Lords expenses claim". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ "Labour peer Lord Taylor of Blackburn dies after mobility scooter crash". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Reporters, Telegraph (30 November 2018). "St Andrew's Day: How did a fisherman become Scotland's patron saint?". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Lorry driver admits causing Lord Taylor of Blackburn's mobility scooter death". BBC News. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Debrett's Peerage. 2003. p. 1560.