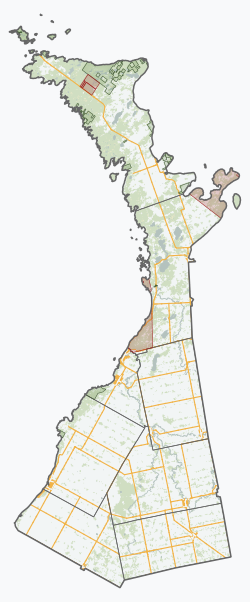

Tobermory is a small community located at the northern tip of the Bruce Peninsula, in the traditional territory of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. Until European colonization in the mid-19th century, the Bruce Peninsula was home to the Saugeen Ojibway nations, with their earliest ancestors reaching the area as early as 7,500 years ago.[1] It is part of the municipality of Northern Bruce Peninsula. It is 300 kilometres (190 miles) northwest of Toronto. The closest city to Tobermory is Owen Sound, 100 kilometres (62 miles) south of Tobermory and connected by Highway 6.

Tobermory | |

|---|---|

Community | |

Little Tub Harbour | |

| Etymology: Named after Tobermory in Scotland | |

| Coordinates: 45°15′N 81°40′W / 45.250°N 81.667°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Bruce County |

| Municipality | Northern Bruce Peninsula |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Area code | 519 |

| Website | tobermory |

Naval surveyor Henry Bayfield originally named this port Collins Harbour.[2] Due to similar harbour conditions it was renamed after Tobermory (/ˌtoʊbərˈmɔːri/; Scottish Gaelic: Tobar Mhoire), the largest settlement in the Isle of Mull in the Scottish Inner Hebrides.

The community is known as the "freshwater SCUBA diving capital of the world"[3] because of the numerous shipwrecks that lie in the surrounding waters, especially in Fathom Five National Marine Park. Tobermory and the surrounding area are popular vacation destinations. The town lies north of the Bruce Peninsula National Park.

The MS Chi-Cheemaun passenger-car ferry connects Tobermory to Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron. Tobermory is also the northern terminus of the Bruce Trail and has twin harbours, known locally as "Big Tub" and "Little Tub". Big Tub Harbour is Canada's largest natural freshwater harbour.[4]

Tobermory is typically a few degrees colder than Toronto. Many businesses in the town are open from May until the Thanksgiving long weekend in October and are closed for the other seven months of the year.

Geography

editThe Government of Ontario has erected a plaque in Tobermory about the geography of the area.[5] The first, at the tip of the peninsula, titled ESCARPMENT SUBMERGENCE, provides this information: "This shoreline marks the northern extremity of the Niagara Escarpment in southern Ontario. Stretching unbroken for 465 miles across southern Ontario from Niagara Falls. The escarpment was created by erosion of layered sedimentary rocks deposited in ancient seas of the Paleozoic Era over 400 million years ago. Portions of the escarpment form the islands between Tobermory and South Baymouth, and the same Paleozoic rocks shape the geology of Manitoulin Island."

In 1857, A. G. Robinson, the chief engineer for Lake Huron lighthouse operations, described the area as being “totally unfit for agricultural purposes."[6] In 1869, Public Land Surveyor Charles Rankin arrived in the area to resurvey the proposed road that would run through the centre of St. Edmonds Township from the Lindsay town line to Tobermory Ontario Harbour. After six weeks of struggle to complete the task, Rankin and his crew returned to their base camp. He summarized in his report that the work had been “one of the most troublesome explorations and pieces of line running ... which I have ever met with."[7] William Bull, a representative of the Indian Department, was sent in 1873 to explore the region to ascertain the amount of good agricultural lands and also the quality and quantity of timber resources. He reported that the town plot and some of the surrounding area were “nearly all burnt off, leaving the white rocky ridges quite bare.” [8]

Despite such warnings, during the 1870s and 1880s, the government sold tracts of land to prospective settlers under the guise of promoting them as agricultural lands. The result was chaotic. Some pioneers arrived and struggled to create farmland, while others came and, after battling the environment and the elements, abandoned the land. Some of these plots were taken over by others, while many tracts remained undeveloped for decades.[9]

One major product taken from the Bruce Peninsula forests was the bark from hemlock trees. On average, about 4,000 cords of hemlock were shipped to tanneries in Kitchener, Acton, Listowel and Toronto.[10]

The first sawmill opened in Tobermory in 1881, and within 20 years, most of the valuable timber was gone. Fires then charred the ravaged landscape, and by the 1920s, the region was nearly bare of forests. The decline of the industry forced settlers out, and the peninsula experienced a steady population decline until the 1970s, when potential cottagers showed new interest in the region and began to buy land.[11]

Bruce Peninsula lumber is no longer a major economic force, but it provided the impetus to settle the region.[12]

Climate

editTobermory has a humid continental climate (Koppen: Dfb) with four distinct seasons. Summers are mild to warm, and winters are cold. Precipitation is well-distributed year-round.[13]

| Climate data for Tobermory (1951–1980) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.7 (53.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −9.9 (14.2) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

1.8 (35.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.6 (−23.1) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 71.9 (2.83) |

46.9 (1.85) |

51.6 (2.03) |

66.3 (2.61) |

54.8 (2.16) |

69.1 (2.72) |

62.8 (2.47) |

73.8 (2.91) |

79.8 (3.14) |

70.5 (2.78) |

75.6 (2.98) |

85.4 (3.36) |

808.5 (31.83) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 12.6 (0.50) |

14.0 (0.55) |

28.6 (1.13) |

66.1 (2.60) |

54.7 (2.15) |

69.1 (2.72) |

62.8 (2.47) |

74.1 (2.92) |

79.8 (3.14) |

70.0 (2.76) |

61.5 (2.42) |

36.6 (1.44) |

629.9 (24.80) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 58.0 (22.8) |

33.0 (13.0) |

22.6 (8.9) |

2.7 (1.1) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

14.1 (5.6) |

49.9 (19.6) |

180.8 (71.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 10 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 99 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 69 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 9 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 31 |

| Source: Environment Canada[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Nature and wildlife

editTobermory is home to many different species of plants and animals. Ancient cedar trees survey along cliff edges and the vast dense forests in Tobermory and the Bruce Peninsula.[16] Black bears and rare reptiles also find refuge in rocky areas of the diverse wetlands of the area.[17]

Some of the more commonly sighted animals include black bears, raccoons, white-tailed deer, porcupines, chipmunks and a variety of snakes. The Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake can also be found in Tobermory, although it is now an endangered species.

Among the many types of plants found in the area, there are around 43 species of wild orchids on the Bruce Peninsula due to its variety of habitats. To celebrate, Tobermory hosts an annual orchid festival in June which includes guided tours and presentations.

At least one species of flower is found growing in Big Tub and no place else in the world.[citation needed]

Massive hauls of lumber in the early 1900s eventually resulted in settlers turning to fishing.[18] Fishermen began dropping nets into Tobermory's deep natural harbours, Big and Little Tub in the late 1800s.[19] The rich fisheries began to decline in the early 1920s due to overfishing and the introduction of the lamprey eel.[20]

Attractions and tourism

editFathom Five National Marine Park

editTobermory is located next to Fathom Five National Marine Park, Canada's first national marine conservation area. The park includes 22 shipwrecks, several historic lighthouses, and glass-bottom cruises from Tobermory.[citation needed]

Lions Head

Known for its lion's-head shape, the eroding cliff edge has served as a tourist destination in Tobermory for the past few decades, and was utilized as a landmark when sailing ships were most common, providing them with shelter from the turbulent Georgian Bay.[21]

Tourism

Tourism is booming in the area, having grown by over 200% in the five years between 2003 and 2008, and is expected to increase in the future.[22]

Bruce Trail

Bruce Trail, a popular hiking trail with magnificent cliff's-edge views of the turquoise water, begins at Tobermory and runs south all the way to Niagara Falls, making it one of Canada's oldest and longest footpaths.[23]

Transportation

editThe main road in town is Ontario Highway 6. It is the northern terminus of the southern segment of the highway as the northern section is interrupted by Georgian Bay. The ferry MS Chi-Cheemaun serves to connect the two sections of Highway 6 during part of the year.

Tobermory Airport is a public (general aviation) airport located south of the town.

In popular culture

editThe science fiction novel Commitment Hour by James Alan Gardner is set in Tober Cove, a post-apocalyptic version of Tobermory.

James Reaney's poem "Near Tobermory, Ontario" describes a cove near the town.

Media

editThe local newspaper is the Tobermory Press.[24]

Radio

editCHEE-FM 89.9 in Tobermory provides seasonal information about the MS Chi-Cheemaun ferry.[25] Operating status of CHEE-FM is unknown.

CBPS-FM 90.7 Bruce Peninsula National Park provides tourism, park and weather information.[26]

CFPS-FM Port Elgin has an FM repeater at Tobermory which operates at 91.9 FM

CHFN-FM 100.1 Neyaashiinigmiing First Nations community radio station

All other radio stations from Owen Sound, including Manitoulin Island, Sudbury, even northeastern Michigan and Central Ontario can also be heard in Tobermory and areas of the northern Bruce Peninsula.

See also

edit- True North II, a boat that sank near Tobermory in 2000

- MS Chi-Cheemaun

- List of unincorporated communities in Ontario

References

edit- ^ "The Ghosts of Tobermory". Adventure Science. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory | Bruce County Welcomes You". brucecounty.on.ca. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Wilkins, Jennifer. "Tobermory: The Freshwater Capital of the World". Dive News Network. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Tobermory Crusader". Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ Cook, Wayne (2013). "Historical Plaques of Bruce County". Wayne Cook. Wayne Cook. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Tobermory Ontario". www.history-articles.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory Ontario". www.history-articles.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory Ontario". www.history-articles.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory Ontario". www.history-articles.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory Ontario". www.history-articles.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "The Ghosts of Tobermory". Adventure Science. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory Ontario". www.history-articles.com. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "Tobermory climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Tobermory weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1951–1980 Volume 2: Temperature". Environment Canada. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1951–1980 Volume 3: Precipitation". Environment Canada. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (2020-11-02). "Bruce Peninsula National Park". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (2020-11-02). "Bruce Peninsula National Park". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Gillard, William H.; Tooke, Thomas R. (1975-12-15). The Niagara Escarpment: From Tobermory to Niagara Falls. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-9755-9.

- ^ "Tobermory | Bruce County Welcomes You". brucecounty.on.ca. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ "The Ghosts of Tobermory". Adventure Science. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Gillard, William H.; Tooke, Thomas R. (1975-12-15). The Niagara Escarpment: From Tobermory to Niagara Falls. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-9755-9.

- ^ "The Ghosts of Tobermory". Adventure Science. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ^ Gillard, William H.; Tooke, Thomas R. (1975-12-15). The Niagara Escarpment: From Tobermory to Niagara Falls. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-9755-9.

- ^ Tobermory Press

- ^ Decision CRTC 99-40, New very low power seasonal radio services to provide information on local ferry services, CRTC, February 17, 1999,

- ^ Decision CRTC 94-613, New low-power FM radio station at Bruce Peninsula National Park, CRTC, August 15, 1994