Thunderheart is a 1992 American Neo-Western mystery film directed by Michael Apted from a screenplay by John Fusco. The film is a loosely based fictional portrayal of events relating to the Wounded Knee incident in 1973,[2] when followers of the American Indian Movement seized the South Dakota town of Wounded Knee in protest against federal government policy regarding Native Americans. Incorporated in the plot is the character of Ray Levoi, played by actor Val Kilmer, as an FBI agent with Sioux heritage investigating a homicide on a Native American reservation. Sam Shepard, Graham Greene, Fred Ward and Sheila Tousey star in principal supporting roles. Also in 1992, Apted had previously directed a documentary surrounding a Native American activist episode involving the murder of FBI agents titled Incident at Oglala. The documentary depicts the indictment of activist Leonard Peltier during a 1975 shootout on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

| Thunderheart | |

|---|---|

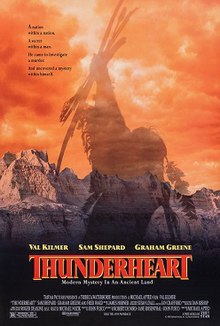

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Apted |

| Written by | John Fusco |

| Produced by | Robert De Niro Jane Rosenthal John Fusco |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Ian Crafford |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | Tribeca Productions Waterhorse Productions |

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English Lakota |

| Box office | $22.6 million[1] |

The film was a co-production between the motion picture studios of TriStar Pictures, Tribeca Productions, and Waterhorse Productions. It was commercially distributed by TriStar Pictures theatrically, and by Columbia TriStar Home Video for home media. Thunderheart explores civil topics, such as discrimination, political activism and murder.[3] Following its cinematic release, the film garnered several award nominations from the Political Film Society. On November 24, 1992, the Original Motion Picture Soundtrack was released by the Intrada Records label. The film score was composed by musician James Horner.

Thunderheart premiered in theaters in-wide release in the United States on April 3, 1992 grossing $22,660,758 in domestic ticket sales. The film was considered a minor financial success after its theatrical run, and was met with generally positive critical reviews before its initial screening in cinemas.

Plot

editLeo Fast Elk, a tribal council member of a Native American reservation in South Dakota, is murdered. FBI Agent Ray Levoi is assigned on the case for his mixed Sioux heritage, which might assist in the inquiry as they interview residents of the reservation. Agent Frank "Cooch" Coutelle narrows down the suspect list to Maggie Eagle Bear, a peaceful Native American political activist and schoolteacher, and Jimmy Looks Twice, leader of the radical Aboriginal Rights Movement (ARM).

Jimmy Looks Twice is the prime suspect, and Frank has been working with tribal council president Jack Milton to apprehend him. Jack has hired an unofficial militia to protect the reservation from Jimmy and the ARM, who oppose the tribal council's efforts to modernize the reservation. Jimmy is eventually taken into custody, but escapes after a gunfight with the FBI and tribal police.

When tribal police officer Walter Crow Horse mentions that the murder took place on Maggie's property, Ray goes to collect evidence and finds bullet casings but is told to leave by Maggie. Ray nonetheless returns to Maggie's to question her grandmother. While Ray is visiting, Maggie's son is shot in the arm by Jack's militia, who claim the shooting was committed by the ARM. Ray drives Maggie and her son to the hospital, getting into a fight with Jack's men in the process.

Although Frank is convinced that Jimmy committed the murder, Walter tells Ray that the killer was heavier than Jimmy is and also stole Leo's car, which was used to take the body from Maggie's property to the dump site. Leo's car is still missing, but Frank dismisses the lead and tells Ray to focus on locating Jimmy. Ray, however, starts his own secret investigation, assisted by Walter and tribal elder Grandpa Sam Reaches. Leo's car is found with a large jacket in the trunk, supporting Walter's claim that the killer was bigger than Jimmy is. Ray surreptitiously takes a raffle ticket stub from the jacket pocket and takes it to Maggie to see if she can identify who it belongs to. Maggie, who organized the raffle, is concerned about the possibility of contaminated water on the reservation.

Ray visits Grandpa Sam Reaches and finds Jimmy, whom he is now convinced is innocent. Despite Ray's efforts, the FBI eventually apprehends Jimmy. Much to Frank's anger, Ray comes to suspect a conspiracy and cover-up involving the reservation and Leo's murder. Meanwhile, Maggie matches the ticket stub for Ray. It was purchased by Richard Yellow Hawk, a convict on the reservation who uses a wheelchair. Ray visits Richard, who admits to killing Leo and pretending to be disabled. Frank and other FBI agents visited Richard in prison, offering to reduce his sentence if he did favors for them. Richard stirred up tensions between the ARM and the tribal council, and was blackmailed by Frank under the threat of returning to prison.

Ray and Walter then travel to Red Deer Table, a location that Leo was investigating prior to his death. Ray previously had a dream about the Wounded Knee Massacre, in which he was running with other Natives from US soldiers. According to Walter, that was a vision, and Ray is "Thunderheart", a Native American hero slain at Wounded Knee, who is now reincarnated to deliver them from their current troubles. The pair eventually discover a government-sponsored plan to strip mine uranium on the reservation. The mining is polluting the water supply and fueling the conflict between the reservation's anti-government ARM and Milton's men. While the land is not owned by Milton, he receives kickbacks from the leases. Ray and Crow Horse discover Maggie's body at the site. Richard is later found dead as well, his wrists slit to make his death look like a suicide.

Walter and Ray are pursued by Frank, Jack, and his pro-government collaborators. Ray reveals that he recorded Richard's confession, implicating Frank in Leo's murder. Ray and Walter are cornered but before they can be killed, the ARM shows up to protect them. Frank and Jack are apprehended after being outnumbered. Ray, disillusioned by the corruption, leaves the FBI.

Cast

edit- Val Kilmer as FBI Agent Ray Levoi

- Sam Shepard as FBI Agent Frank 'Cooch' Coutelle

- Graham Greene as Walter Crow Horse

- Fred Ward as Jack Milton

- Fred Thompson as William Dawes

- Sheila Tousey as Maggie Eagle Bear

- Ted Thin Elk as Grandpa Sam Reaches

- John Trudell as Jimmy Looks Twice

- Julius Drum as Richard Yellow Hawk

- Sarah Brave as Grandma Maisy Blue Legs

- Allan R.J. Joseph as Leo Fast Elk

- Sylvan Pumpkin Seed as Hobart

- Patrick Massett as FBI Agent Mackey

- Rex Linn as FBI Agent

- Brian A. O'Meara as FBI Agent

- Candy Hamilton as Schoolteacher

- David Crosby as Bartender

Production

editFilming

editThe film was shot primarily on location in South Dakota.[4] Specific sets included the Pine Ridge Reservation, which was dubbed the Bear Creek Reservation. Other filming locations used were in the Washington, D.C. area for the opening sequences.[4] The film employed many Native American actors, some of whose screen roles mirror their real lives.[2] The actor John Trudell, who played an Indian activist suspected of murder in the film inspired by the real-life events surrounding Leonard Peltier, was in fact a Native American activist, as well as a poet and singer.[2] Chief Ted Thin Elk, who played an honored Lakota medicine man, was a Lakota elder himself.[2] Badlands National Park and Wounded Knee in South Dakota were also used as backdrop locations for the real-life incidents which took place during the 1970s.[5] Filming was done with the support of the Oglala Sioux people, who trusted Apted and Fusco to express their story.[5]

Soundtrack

editThe original motion picture soundtrack for Thunderheart was released by the Intrada Records music label on November 24, 1992.[6] The score for the film was composed by James Horner, while original songs written by musical artists Bruce Springsteen, Ali Olmo, and Sonny Lemaire, among others, were used in-between dialogue shots throughout the film. Jim Henrikson edited the film's music.[4]

| Thunderheart: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Film score by | |

| Released | 11/24/1992 |

| Length | 43:59 |

| Label | Intrada Records |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Main Title" | 2:13 |

| 2. | "The Oglala Sioux" | 2:38 |

| 3. | "Jimmy's Escape" | 3:34 |

| 4. | "Proud Nation" | 1:59 |

| 5. | "Evidence" | 1:40 |

| 6. | "First Vision" | 1:16 |

| 7. | "Ghost Dance" | 3:16 |

| 8. | "The Goons" | 2:36 |

| 9. | "Medicine Man" | 1:02 |

| 10. | "My People/Wounded Knee" | 4:30 |

| 11. | "Thunderheart" | 5:26 |

| 12. | "Run for the Stronghold" | 5:25 |

| 13. | "This Land is Not For Sale/End Titles" | 8:24 |

| Total length: | 43:59 | |

Marketing

editNovel

editA paperback novel published by HarperCollins titled Thunderheart based on John Fusco's screenplay, was released on May 28, 1992. The book dramatizes the fictionalized events of the Wounded Knee Incident, as depicted in the film. It expands on the ideas of how an FBI agent's assignment to uncover the truth behind violence on an Indian reservation leads to a wide-range conspiracy.[7]

Reception

editCritical response

editRotten Tomatoes reported that 90% of 20 sampled critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 6.4 out of 10.[8] Following its cinematic release in 1992, Thunderheart received two nominations from the Political Film Society Awards in the categories of Exposé and Human Rights.[9]

| "A film this intent on authenticity might easily grow dull, but this one doesn't; Mr. Apted is a skillful storyteller. He gives 'Thunderheart' a brisk, fact-filled exposition and a dramatic structure that builds to a strong finale, one that effectively drives the film's message home." |

| —Janet Maslin, writing in The New York Times[2] |

Chris Hicks, of the Deseret News, said screenwriter Fusco and director Apted created a "rich backdrop, with fascinating character development and a serious focus on the spirituality of Indian beliefs." He commented that "there's a lot more going on in Thunderheart that makes it well worth the trip—not the least of which is the performance of co-star Graham Greene, fresh from his Oscar-nominated Dances With Wolves triumph, wonderful as a wise-cracking American Indian cop."[10] In a mixed review, Variety believed the film found "a lively platform for its essential view that the old ways were far wiser and better." However, they noted that actor Kilmer "holds the screen strongly in an intense young Turk role, but when script calls for him to transform into a mythical Indian savior, he doesn't quite fill the moccasins."[11] Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times offered a positive review recalling how he thought "what's most absorbing about Thunderheart is its sense of place and time. Apted makes documentaries as well as fiction films, and in such features as Coal Miner's Daughter and Gorillas in the Mist and such documentaries as 35 Up he pays great attention to the people themselves - not just what they do, and how that pushes things along."[12]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times said the film had "the shape of a thriller" and a "documentary's attentiveness to detail". She also said that the "film's outstanding performance comes from Graham Greene, an Oscar nominee for Dances with Wolves, a film that looks like an utter confection beside this plainer, harder-hitting drama.... Mr. Greene proves himself a naturally magnetic actor who deserves to be seen in other, more varied roles."[2] Critic Kathleen Maher for The Austin Chronicle viewed Thunderheart as an "element of misty romanticism about Native Americans that Apted just doesn't manage to pull off. His yarn, however, is a good one even if it could be told a little better." However, she added that "Apted manages to say a lot by cutting between the squalor of life on the reservation to the magnificence of the land around it. Unfortunately, when the characters speak for themselves, they are often forced to deliver lines that are unspeakable."[13] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a C rating calling it "hokey" and "laborious". He viewed the film as a "leftover 1970s conspiracy thriller were it not for the novelty of its setting: a modern Indian reservation—which, as the movie reveals, is by now a fancy word for slum." He did however compliment actor Greene, calling his performance—the film's "one redeeming feature".[14] Author C.M. of Time Out said that "Apted and cinematographer Roger Deakins focus unblinkingly on the poverty endemic to the reservation. This directness, however, contrasts with an over-complicated script by John Fusco." But he acknowledged that "the story boasts integrity and serves as a forceful indictment of on-going injustice."[15]

| "In Thunderheart we get a real visual sense of the reservation, of the beauty of the rolling prairie and the way it is interrupted by deep gorges, but also of the omnipresent rusting automobiles and the subsistence level of some of the housing." |

| —Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times[12] |

Sean Axmaker of Turner Classic Movies boasted on the film's merits by declaring, "Thunderheart dispenses with clichés of Indian culture while respectfully showing the traditions kept alive on the reservation and exposing conditions on the reservation, all within the conventions of an entertaining and involving Hollywood murder mystery with a message."[5] Rating 3 Stars, Leonard Maltin wrote that the film was an "engrossing thriller" that is "notable for its keen attention to detail regarding Sioux customs and spirituality, and its enlightened point of view."[16]

Box office

editThe film premiered in cinemas on April 3, 1992 in wide release throughout the U.S.. During its opening weekend, the film opened in 5th place grossing $4,507,425 in business showing at 1,035 locations.[1] The film White Men Can't Jump came in first place during that weekend grossing $10,188,583.[17] The film's revenue dropped by 26% in its second week of release, earning $3,324,500. For that particular weekend, the film fell to 8th place screening in 1,090 theaters. The film Sleepwalkers unseated White Men Can't Jump to open in first place grossing $10,017,354 in box office revenue.[18] During its final weekend in release, Thunderheart opened in a distant 14th place with $1,111,110 in revenue.[19] The film went on to top out domestically at $22,660,758 in total ticket sales through a six-week theatrical run.[1] For 1992 as a whole, the film would cumulatively rank at a box office performance position of 55.[20]

Home media

editFollowing its theatrical release, the film was released on VHS video format on October 14, 1992.[21] The Region 1 Code widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on September 29, 1998.[22] The film was released on Blu-ray on May 21, 2024. A digital release of the 4K screening of the film is also currently available to purchase and stream.[23]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "Thunderheart". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Maslin, Janet (April 3, 1992). Thunderheart (1992) Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Michael Apted. (1992). Thunderheart [Motion picture]. United States: TriStar Pictures.

- ^ a b c "Thunderheart (1992)". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c Axmaker, Sean (1992). Thunderheart. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ "Thunderheart Soundtrack". Amazon. Archived from the original on September 14, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Charters, Lowell (May 28, 1992). Thunderheart. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-380-76881-3.

- ^ "Thunderheart (2018)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on July 25, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ Previous Political Film Society Award Winners Archived January 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Political Film Society Awards. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Hicks, Chris (April 8, 1992). Thunderheart Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Deseret News. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Variety, (December 31, 1991). Thunderheart Archived November 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (April 3, 1992). Thunderheart Archived October 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Maher, Kathleen (April 10, 1992). Thunderheart Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (April 17, 1992). Thunderheart Archived September 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ C.M. (1992). Thunderheart Archived October 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Time Out. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (August 5, 2008). Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide. Signet. p. 1,414. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ "April 3–5, 1992 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "April 10–12, 1992 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "May 8–10, 1992 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "1992 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Thunderheart VHS Format. Amazon.com. ISBN 0800115821.

- ^ "Thunderheart - DVD". SonyPictures.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Thunderheart Blu-ray".

Further reading

edit- Aleiss, Angela (2005). Making the White Man's Indian: Native Americans and Hollywood Movies. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-98396-3.

- Brown, Dee (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 9780030853227.

- Brown, H. (2007). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Holt Paperbacks. ASIN B00434EYM4.

- Claypoole, Antoinette Nora (2013). Ghost Rider Roads: Inside the American Indian Movement Archived September 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. Wild Embers Press Archived September 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. ASIN 1475048580.

- Coleman, William (2001). Voices of Wounded Knee. Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-6422-9.

- Flood, Renee (1998). Lost Bird of Wounded Knee: Spirit of the Lakota. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80822-7.

- Gitlin, Martin (2010). The Wounded Knee Massacre. Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-59884-409-2.

- Gonzalez, Mario (1998). The Politics of Hallowed Ground: Wounded Knee and the Struggle for Indian Sovereignty. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06669-6.

- King, Mike (2008). The American Cinema of Excess: Extremes of the National Mind on Film. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3988-1.

- Lyman, Stanley (1993). Wounded Knee 1973: A Personal Account. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7933-9.

- Mann, Abby (1979). Massacre at Wounded Knee. Zebra Books. ASIN B00136MNIC.

- Marubbio, Elise (2006). Killing the Indian Maiden: Images of Native American Women in Film. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2414-8.

- Milligan, Edward (1973). Wounded Knee 1973 and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Edward A. Milligan. ASIN B0028ILJ0M.

- O'Neill, Laurie (1994). Wounded Knee: The Death of a Dream. Demco Media. ISBN 978-0-606-06894-9.

- Richardson, Heather (2010). Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre. Basic Books. ASIN B004LQ0G6C.

- Seymour, Forrest (1981). Sitanka: The Full Story of Wounded Knee. Christopher Pub. House. ISBN 978-0-8158-0399-7.

- Silvestro, Roger (2005). In the Shadow of Wounded Knee: The Untold Final Chapter of the Indian Wars. Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1461-9.

- Smith, Rex (1981). Moon of Popping Trees. Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-9120-1.

- Utter, Jack (1991). Wounded Knee and the Ghost Dance Tragedy. National Woodlands Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-9628075-1-0.