The Return of Navajo Boy (released in 2000) is a documentary film produced by Jeff Spitz and Bennie Klain about the Cly family, Navajo who live on their reservation. Through them, the film explores several longstanding issues among the Navajo and their relations with the United States government and corporations: environmental racism, media and political representation, off-reservation adoption, and denial of reparations for environmental illnesses due to uranium mining in Monument Valley, Utah, which was unregulated for decades.[1] Bill Kennedy served as the film's executive producer; his late father had produced and directed the earlier silent film The Navajo Boy (1950s), which featured the Cly family.

| The Return of Navajo Boy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Jeff Spitz |

| Starring | Cly Family |

Release date |

|

Running time | 52 min. |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English Navajo |

In 2000, the film was an official selection of the Sundance Film Festival. It has won numerous awards.[2]

The Cly family

editThe producers wanted to tell the full story of the Cly family, who were residents of the Navajo Nation in Monument Valley, Utah. They had earlier been the subjects in the silent film The Navajo Boy. Through their story, the director and family intended to explore many of the issues with which the Navajo Nation has had to struggle since the early 20th century: land use and environmental contamination, off-reservation adoptions, health education, enforcement of treaty rights, relations with the United States government.

Much of the story in the 2000 film is told by the chief subject, Elsie Mae Cly Begay, the eldest of the children shown in The Navajo Boy. She is the oldest living Cly featured in the 2000 film. Her mother Happy Cly died of lung cancer, which the family believed was caused by environmental contamination from unregulated uranium mining on the reservation. Elise Mae Begay has lost two sons, one to lung cancer and the other to a tumor, whose deaths she attributes to uranium contamination near the house where they lived when her sons were children. (Constructed in part of contaminated rock, the structure was torn down in 2001.)[3])

As uranium was mined for four decades in six regions on the reservation, the result has been numerous sites of abandoned mine residues and tailings, including near Begay's former home. In some areas, families used contaminated rock to build their homes. The air and water have also been contaminated. "By the late 1970s when the mines began closing, some miners were dying of lung cancer, emphysema or other radiation-related ailments."[3]

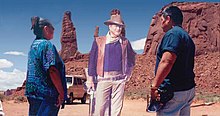

At the time of Happy Cly's death, her youngest son John Wayne Cly was an infant. Christian missionaries adopted the boy. Elsie Mae Begay insists that the family agreed only to have her brother John cared for, but that he was to be returned to the family when he was six years old. They lost track of him, but through the making of the film, the Cly family was reunited with their long-estranged brother John Wayne Cly.[1]

Elsie Mae's late grandparents, Happy and Willie Cly, were the main subjects of the earlier film. The "Navajo Boy" for whom the original film was named was Jimmy Cly, Elsie Mae's cousin.[1]

Film's reception

editThe Return of Navajo Boy was aired on PBS November 13, 2000 List of Independent Lens films#Season 2 (2000). It has won awards at film festivals and is regularly screened at activist events, in public libraries and colleges, where it used for education related to the issues covered in the film.[4]

Elsie Mae Begay has become a public activist, telling her family and the Navajo Nation's story on college campuses and to Congress, to try to have practices changed and such health hazards controlled.[3] Her daughter-in-law, Mary Helen Begay, has been filming webisodes of the EPA clean-up effort, with a camera supplied by Groundswell Educational Films, which produced the documentary.

With an updated epilogue in 2008, the film was shown on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC to Congressional and EPA staff.[5] In 2008 Congress authorized a five-year, five-agency clean-up plan to mitigate environmental contamination on the Navajo reservation.[6]

Since the film was made, Bernie Cly, one of the Navajo family featured, has been awarded $100,000 in compensation from the US government under the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. The legislation was passed to compensate mine workers and residents for environmental damages due to uranium mining, especially from the 1950s through the 1970s, as the US government was the sole purchaser of the product.[6]

Changes in law and practice

editThe Navajo Nation had long been concerned about the effects of uranium mining on their members at the reservation, due to longterm effects from direct and indirect exposure to contaminants. Their EPA has identified numerous sites that need hazardous waste remediation. In 2005, the Nation was the first indigenous nation to prohibit such mining on its reservation.[3]

Following identification of contaminated water and structures, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Navajo Nation have developed a five-year, multi-agency plan to clean up contamination from the sites.[3] In 2011, it was completing the first major project, to remove 20,000 cubic yards of materials from the abandoned Skyline Mine, near Begay's former home. Progress on reservation uranium clean-up by the government is documented with video webisodes online.[3]

In early 2010, the Indian Health Service began using the documentary as an outreach tool to raise awareness about uranium contamination and health issues on the Navajo Nation reservation.[7] In 2014, Amy Goodman used segments from The Return of Navajo Boy to illustrate the effects of uranium mining on Navajo land as part of the Democracy Now! program, "A Slow-Motion Genocide."[8]

Honors

edit- Official selection, 2000 Sundance Film Festival

- Best Documentary, Indian Summer Festival

- Programmer's Choice Award, Planet in Focus Festival

- Audience Award, Durango International Film Festival

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "The Return of Navajo Boy". Wiley InterScience.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Felicia Fonseca, "Navajo woman helps prompt uranium mine cleanup", Associated Press, carried in Houston Chronicle, 5 September 2011, accessed 5 October 2011

- ^ "Screenings", Return of Navajo Boy Website

- ^ "Washington, DC Premiere of Return of Navajo Boy, with updated Epilogue", Groundswell Films

- ^ a b Jennifer Amdur Spitz, "Navajo Film & Media Campaign Win Clean Up of Uranium", Press Release, 22 August 2011, accessed 5 October 2011

- ^ "Indian Health Service uses film to launch Navajo health tour, Groundswell Films

- ^ ""A Slow Genocide of the People": Uranium Mining Leaves Toxic Nuclear Legacy on Indigenous Land". Democracy Now!.

External links

edit- The Return of Navajo Boy, Official Website, includes links to Webisodes of EPA clean-up of reservation