The Great Yokai War (Japanese: 妖怪大戦争, Hepburn: Yōkai Daisensō) is a 2005 Japanese fantasy film directed by Takashi Miike, produced by Kadokawa Pictures and distributed by Shochiku. The film stars Ryunosuke Kamiki, Hiroyuki Miyasako, Chiaki Kuriyama, and Mai Takahashi.

| The Great Yokai War | |

|---|---|

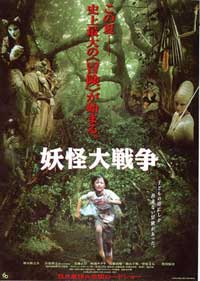

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Takashi Miike |

| Written by | Novel: Hiroshi Aramata Screenplay: Takashi Miike Mitsuhiko Sawamura Takehiko Itakura |

| Produced by | Tsuguhiko Kadokawa Fumio Inoue |

| Starring | Ryunosuke Kamiki Hiroyuki Miyasako Mai Takahashi |

| Cinematography | Hideo Yamamoto |

| Edited by | Yasushi Shimamura |

| Music by | Kōji Endō |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Shochiku |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | ¥1.3 billion |

| Box office | ¥2 billion (Japan)[1] |

The film focuses largely on creatures from Japanese mythology known as yōkai (妖怪, variously translated as "apparition", "goblin", "ghoul", "spirit", or "monster"), which came to prominence during the Edo period[2] with the works of Toriyama Sekien.[3] It also draws inspiration from Aramata Hiroshi's Teito Monogatari, with the novel's antagonist Katō Yasunori appearing as the main antagonist in the film.[4]

The film is considered a loose remake of the 1968 Daiei film Yokai Monsters: Spook Warfare, but also draws influence from Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitarō manga series of the same name. Additionally, Daiei Film's iconic tokusatsu characters Gamera and Daimajin that have influenced productions of the company's yokai films including Yokai Monsters,[5] were also briefly mentioned both in the film and the novelization of the 2005 film.[a]

All three are retellings of the famous Japanese tale of Momotarō, which features the title character driving a group of demons away from Kikaigashima with the help of native animals.[6] While these previous adaptations have been read mostly as nationalist narratives, with the native yōkai driving out invading forces,[7] The Great Yōkai War has been read instead for the clash between Japan's traditional landscape and its modern culture.[8] This is largely due to the film's use of kikai (機械, lit. "machine monsters"), created by Katō fusing the yōkai with machines, and the absence of invading Western or otherwise foreign forces.[9]

Mizuki, whose work is considered an important part of yōkai discourse and culture due to his contributions in pop culture and academic study, acted as an advisor for the film and even made an appearance as the Great Elder Yōkai.[10] The cameo is not only a nod to Mizuki's status as a yōkai expert, but his closing words also resonate closely with the theme of his manga of the same name.[11] Similarly, his role as a peace-keeper is one referenced throughout his work, and is born of his own experiences from real war.[12]

The Great Yokai War was theatrically released in Japan on August 6, 2005, and grossed ¥2 billion. In 2006, the film was released internationally by Tokyo Shock. A sequel, was released in Japan on August 13, 2021.

Plot

editA young boy named Tadashi Ino moves to a small town after his parents' divorce. At a local festival, he is chosen to be that year's Kirin Rider, referring to the legendary Chinese chimera, the Qilin:[b] a protector of all things good. He soon discovers that his new title is quite literal, as a nefarious spirit named Yasunori Katō appears. Katō - a demon whose mystical powers are born of his rage at the annihilation of Japan's local tribes - desires vengeance against the modern Japanese for their actions against the yōkai.[11] To carry out his revenge, Katō allies himself with a yōkai named Agi, summoning a fiery spirit called Yomotsumono: a creature composed of the resentment carried by the multitudinous things mankind has discarded. Katō feeds yokai into Yomotsumono's flames, fusing them with the numerous discarded tools and items to form kikai. These kikai - under Katō's control - capture other yōkai to build their numbers while killing humans. One such yokai, a sunekosuri[c] escapes and befriends Tadashi who attempts to obtain the Daitenguken[d] from the mountain as a right of passage for the role of Kirin Rider.

Scared by the tales told of the mountain, Tadashi falters upon his arrival at the mountain and tries to flee. However, tricked by the sea spirit Shōjō,[e] who picked Tadashi out, he manages to overcome a test to prove his worth. Accompanied by Shōjō, Kawahime,[f] and Kawatarō,[g] Tadashi makes his way to the Daitengu[h] who gives him the sword before being taken away by the kikai. In spite of Tadashi's attempts, the sword is broken as Agi takes the sunekosuri as her captive before the boy is knocked unconscious.

When Tadashi comes to his senses, he finds himself among yōkai as they discuss how to fix the sword; they ultimately decide to request the aid of the blacksmith Ippondatara.[i] Upon learning that Ippondatara was also captured, General Nurarihyon[j] and his group leave. Kawataro restrains an ittan-momen,[k] praising the bumbling Azukiarai,[l] unaware that he only remained behind due to his foot getting numb.

When Katō's industrial fortress takes flight towards Tokyo, Tadashi and company pursue it. They arrive shortly after the fortress ingests Tokyo's Shinjuku Capital Building, finding Ippondatara who reforges the sword. Ippondatara refuses to talk about how he escaped, ashamed that the sunekosuri took his place in becoming a kikai. Donning new attire, Tadashi and company go into battle. They are greatly outnumbered until they receive unlikely aid from thousands of yōkai who believe they are coming to a party; their festival brawl with the kikai allows Tadashi and Kawahime to enter the fortress safely, followed by a yōkai-obsessed reporter named Sata whom Kawahime saved in the past.

Tadashi is forced to slay the kikai that the sunekosuri became, restoring it to its original form yet leaving it gravely injured. In a rage, Tadashi battles Agi before she is called back by Katō to begin the final phase by joining with Yomotsumono. Despite Tadashi's attempts, Katō outmatches him. Kawahime attempts to protect the boy, stating that while she hates humans due to them abandoning her, she has no desire for revenge as she considers it a human emotion. Unfazed, Katō takes the two out as Azukiarai awkwardly arrives.

Katō calls Agi to join him. However, her love for him is a hindrance to the process, so Katō kills her instead before entering the oven to become one with Yomotsumono. However, due to Sata's actions, one of Azukiarai's adzuki beans ends up in the mix with Katō, causing a chain reaction of positive emotion that destroys Yomotsumono.

After the yokai take their leave, Tadashi and Sata find themselves on the street and the boy tells his first white lie to the reporter about Kawahime's feelings towards him. Years later, Tadashi is a grown man who has lost the ability to see yokai, even the sunekosuri. The film ends with the sunekosuri being confronted by an Azuki-pupiled Katō.

Cast

edit| Role | Actor |

|---|---|

| Tadashi Ino | Ryunosuke Kamiki |

| Sata | Hiroyuki Miyasako |

| Kawahime | Mai Takahashi |

| Shōjō | Masaomi Kondo |

| Kawataro | Sadao Abe |

| Azukiarai | Takashi Okamura |

| Ippon-datara | Hiromasa Taguchi |

| Yasunori Katō | Etsushi Toyokawa |

| Agi, The Bird-Catching Sprite | Chiaki Kuriyama |

| Shuntaro Ino | Bunta Sugawara |

| Youko Ino | Kaho Minami |

| Tataru Ino | Riko Narumi |

| General Nurarihyon | Kiyoshiro Imawano |

| Abura-sumashi | Naoto Takenaka |

| Oh Tengu | Kenichi Endō |

| Great Yōkai Elder (cameo) | Shigeru Mizuki |

Featured yōkai

editNotes

edit- ^ For instance, a witness called the monstrous flying creature "Yomotsumono" as "Gamera" when it flew by a castle.

- ^ 麒麟, usually translated as "unicorn"

- ^ 脛擦り, lit. "shin rubber"

- ^ 大天狗剣, lit. "great Tengu sword"

- ^ 猩々, lit. "heavy drinker" or "orangutan"

- ^ 川姫, lit. "river princess"

- ^ 川太郎, lit. "river-boy"

- ^ 大天狗, lit. "great Tengu"

- ^ 一本踏鞴, lit. "one-legged bellows"

- ^ 滑瓢, lit. "slippery gourd"

- ^ 一反木綿, lit. "one tan (a unit of measurement) of cotton"

- ^ 小豆洗い, lit. "bean washer"

References

edit- ^ http://www.eiren.org/toukei/img/eiren_kosyu/data_2005.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Suzuki 2011, p. 232.

- ^ Shamoon 2013, p. 277.

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 233.

- ^ 甦れ!妖怪映画大集合!! 2005, p.97, p.116-119, Takeshobo

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 227.

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 230.

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 233-234.

- ^ Papp 2009, p. 234.

- ^ Foster 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b Lukas & Marmysz 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Foster 2009, p. 173-174.

Bibliography

edit- Foster, Michael Dylan (2008-11-05). "The Otherworlds of Mizuki Shigeru". Mechademia. 3: 8–28. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0097. JSTOR 41510900. S2CID 123250950.

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2009-11-11). "Haunted Travelogue: Hometowns, Ghost Towns, and Memories of War". Mechademia. 4: 164–181. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0026. JSTOR 41510934. S2CID 119839953.

- Lukas, Scott A.; Marmysz, John (2010). Fear, Cultural Anxiety, and Transformation: Horror, Science Fiction, and Fantasy Films Remade. Plymouth: Lexington Books. p. 139. ISBN 9780739124895.

- Papp, Zília (2009). "Monsters at War: The Great Yōkai Wars, 1968–2005". Mechademia. 4 (1): 225–239. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0073. ISSN 2152-6648.

- Shamoon, Deborah (2013). "The Yōkai in the Database: Supernatural Creatures and Folklore in Manga and Anime". Marvels & Tales. 27 (2): 276–289. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276. ISSN 1536-1802. JSTOR 10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276. S2CID 161932208.

- Suzuki, CJ (Shige) (2011). "Learning from Monsters: Mizuki Shigeru's Yōkai and War Manga". Image & Narrative. 12 (1): 229–244. ISSN 1780-678X.[permanent dead link]