The Deer Hunter is a 1978 American epic war drama film co-written and directed by Michael Cimino about a trio of Slavic-American[3][4][5] steelworkers whose lives are upended after fighting in the Vietnam War. The three soldiers are played by Robert De Niro, Christopher Walken and John Savage, with John Cazale (in his final role), Meryl Streep and George Dzundza in supporting roles. The story takes place in Clairton, Pennsylvania, a working-class town on the Monongahela River south of Pittsburgh, and in Vietnam.

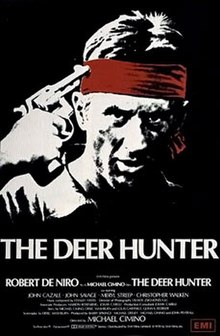

| The Deer Hunter | |

|---|---|

UK cinema release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Cimino |

| Screenplay by | Deric Washburn Michael Cimino (uncredited) |

| Story by | Deric Washburn Michael Cimino Louis A. Garfinkle Quinn K. Redeker |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Vilmos Zsigmond |

| Edited by | Peter Zinner Michael Cimino (uncredited) |

| Music by | Stanley Myers |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 184 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English Russian Vietnamese French |

| Budget | $15 million[2] |

| Box office | $49 million[2] |

The film was based in part on an unproduced screenplay called The Man Who Came to Play by Louis A. Garfinkle and Quinn K. Redeker about Las Vegas and Russian roulette. Producer Michael Deeley, who bought the script, hired Cimino who, with Deric Washburn, rewrote the script, taking the Russian roulette element and placing it in the Vietnam War. The film went over-budget and over-schedule, costing $15 million. Its producers EMI Films released it internationally, while Universal Pictures handled its North American distribution.

The Deer Hunter received acclaim from critics and audiences, with praise for Cimino's direction, the performances of its cast, its screenplay, realistic themes and tones, and cinematography. It was also successful at the box office, grossing $49 million. At the 51st Academy Awards, it was nominated for nine Academy Awards, and won five: Best Picture, Best Director for Cimino, Best Supporting Actor for Walken, Best Sound, and Best Film Editing. It was Meryl Streep's first Academy Award nomination (for Best Supporting Actress).

The Deer Hunter has been included on lists of the best films ever made, including being named the 53rd-greatest American film of all time by the American Film Institute in 2007 in their 10th Anniversary Edition of the AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies list. It was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 1996, as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[6][7]

Plot

editIn 1968, three friends in a tight-knit Slavic American[3][a] community in Western Pennsylvania—Mike Vronsky, Steven Pushkov, and Nikanor "Nick" Chevotarevich—work in a steel mill and hunt deer with their co-workers Stanley ("Stan") and Peter "Axel" Axelrod, along with friend and bartender John Welsh. Mike, Steven, and Nick are preparing to leave for military service in Vietnam. Steven is engaged to Angela Ludhjduravic, who was secretly impregnated by another man. Mike and Nick are close friends who live together and both love Linda, who will be moving into their home to escape from her alcoholic father. While dancing at Steven and Angela's wedding, Linda accepts Nick's spontaneous marriage proposal. Nick implores Mike to ensure he returns from Vietnam. Mike, Nick, and their friends go on a final hunting trip. Mike kills a deer with a single shot.

In 1969 in Vietnam, Mike, now a Green Beret, happens upon Nick and Steven, who land in a village during an Air Assault mission. The three are soon imprisoned by the Viet Cong in a cage along a river and forced to participate in games of Russian roulette while the jailers bet. Steven fires his round at the ceiling and is forced into a cage with rats and previous victims of the jailers. Mike convinces his captors to put three bullets into the revolver's cylinder. Mike kills two captors as he and Nick overpower their captors, however, Nick is wounded in the leg. They quickly escape, rescuing Steven in the process.

The trio floats down the river on a felled tree trunk, but Nick and Steven are weak from their wounds. They are rescued by an American helicopter, but Steven falls back into the river while trying to grab onto the helicopter skids. Nick boards, however, Mike drops down to help Steven, whose legs are broken in the fall. Mike carries him until they meet refugees and a South Vietnamese Army convoy fleeing to Saigon.

Nick is treated at a U.S. military hospital. Once released, Nick, now suffering from PTSD, wanders into a gambling den. French businessman Julien Grinda persuades him to come inside. Upset, Nick interrupts a game of Russian roulette, pulling the trigger on himself. Mike happens to be present as a spectator, but Nick and Julien hurriedly leave.

Sometime later, Mike returns home, but cannot integrate into civilian life. He avoids a welcome-home party, opting to stay alone in a hotel. He visits Linda and learns that Nick has deserted. Mike then visits Angela, who is now a mother, but has slipped into catatonia following the return of Steven, who has lost both of his legs in the war. Stan, Axel, and John understand nothing of war or what Mike has experienced. Linda and Mike find comfort in each other's company. During a hunting trip, Mike stops himself from shooting a deer and returns to the cabin where he finds Stan cavalierly threatening Axel with his pistol. Mike takes it, chambering a single round, and triggers an empty chamber at Stan's head.

Mike visits Steven at a veterans' hospital; both of Steven's legs have been amputated, and he has lost the use of an arm. Steven refuses to come home, saying he no longer fits in. He tells Mike that he has been regularly receiving large sums of money from Vietnam. Mike intuits that Nick is the source of these payments, and forces Steven to return home to Angela. Mike returns to Vietnam in search of Nick. Wandering around Saigon, which is now in a state of chaos shortly before its fall, Mike finds Julien and persuades him to take him to the gambling den. Mike finds himself facing Nick, who has become a professional in the macabre game and fails to recognize Mike. Mike attempts to bring Nick back to reason by invoking memories of their hunting trips back home, but Nick maintains his indifference. However, during a game of Russian roulette between Mike and Nick, Nick recalls Mike's "one shot" method and smiles before pulling the trigger and killing himself.

Mike and his friends attend Nick's funeral, and the atmosphere at their local bar is dim and silent. Moved by emotion, John begins to sing "God Bless America" in honor of Nick, as everyone joins in.

Cast

edit- Robert De Niro as Staff Sergeant Mikhail Vronsky ("Mike"). After Roy Scheider withdrew from the cast two weeks before the start of filming over creative differences, producer Michael Deeley pursued De Niro, who was paid one million dollars for the role,[8] in search of star power to sell a film with a "gruesome-sounding storyline and a barely known director."[9] De Niro later said: "I liked the script, and [Cimino] had done a lot of prep. I was impressed."[10] He prepared by socializing with steelworkers in local bars and by visiting their homes.[11] De Niro claimed this was his most physically exhausting film and that the sequence in which Mike visits Steven in the hospital was the most emotional scene of his career.[12]

- Christopher Walken as Corporal Nikanor Chevotarevich ("Nick"). His performance won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

- John Savage as Corporal Steven Pushkov

- John Cazale as Stanley ("Stan"/"Stosh"). All scenes involving Cazale, who had terminal cancer, were filmed first. Because of his illness, the studio wanted to dismiss him, but Streep, with whom he was in a romantic relationship, and Cimino threatened to withdraw from the project if Cazale was released.[13][14] He was also uninsurable, and according to Streep, De Niro paid for his insurance because he wanted Cazale in the film. This was Cazale's last film, as he died shortly after filming wrapped. Cazale never saw the finished film.[13][15]

- Meryl Streep as Linda. In the screenplay, Streep's role was negligible, but Cimino explained the role to her and suggested that she write her own lines.[16]

- George Dzundza as John Welsh

- Pierre Segui as Julien Grinda

- Shirley Stoler as Steven's mother

- Chuck Aspegren[17][18] as Peter Axelrod ("Axel"). Aspegren was not an actor; he was the foreman at an East Chicago steel factory visited early in preproduction by De Niro and Cimino. They were so impressed with him that they offered him the role. He was the second person to be cast in the film after De Niro.[11]

- Rutanya Alda as Angela Ludhjduravic-Pushkov

- Paul D'Amato as Sergeant

- Amy Wright as Bridesmaid

- Joe Grifasi as Bandleader

- John F. Buchmelter III as a bar patron. Buchmelter was a steel worker whom Cimino wanted in order to lend the film a sense of authenticity.

While Deeley was pleased with the revised script, he was still concerned about being able to sell the film. He later wrote: "We still had to get millions out of a major studio, as well as convince our markets around the world that they should buy it before it was finished. I needed someone with the caliber of Robert De Niro."[19] Deeley felt that De Niro was "the right age, apparently tough as hell, and immensely talented."[9]

De Niro, who knew many actors in New York, brought Streep and Cazale to the attention of Cimino and Deeley.[20] De Niro also accompanied Cimino to scout locations for the steel mill sequence and rehearsed with the actors to use the workshops as a bonding process.[21]

Each of the six principal male characters carried a photo in his back pocket depicting them all together as children in order to enhance the sense of camaraderie among them. Cimino instructed the props department to fashion complete photo IDs for each of them, including driver licenses and medical cards, to enhance each actor's sense of his character.[22]

Production

editPreproduction

editThere has been considerable debate and controversy about how The Deer Hunter was initially developed and written.[10] Director and cowriter Michael Cimino, writer Deric Washburn and producers Barry Spikings and Michael Deeley all have different versions of how the film came to be.

Development

editIn 1968, record company EMI formed a new company, EMI Films, headed by producers Barry Spikings and Deeley.[10] Deeley purchased the first draft of a spec script called The Man Who Came to Play, written by Louis A. Garfinkle and Quinn K. Redeker, for $19,000.[23] It was about people who go to Las Vegas to play Russian roulette.[10] Deeley later wrote: "The screenplay had struck me as brilliant, but it wasn't complete. The trick would be to find a way to turn a very clever piece of writing into a practical, realizable film."[24] When the film was being planned during the mid-1970s, the Vietnam War was still a taboo subject with all major Hollywood studios.[23] According to Deeley, the standard response was that "no American would want to see a picture about Vietnam."[23]

After consulting various Hollywood agents, Deeley found Cimino[24] and was impressed by Cimino's television commercial work and crime film Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974).[24][25] Cimino was confident that he could further develop the principal characters of The Man Who Came to Play without losing the essence of the original. According to Deeley, Cimino questioned the need for the Russian roulette element of the script, but Redeker fervently fought to preserve it. Cimino and Deeley discussed the work needed in the first part of the script, and Cimino believed that he could develop the stories of the main characters in the film's first 20 minutes.[25]

Screenplay

editCimino worked for six weeks with Deric Washburn on the script.[11] Cimino and Washburn had previously collaborated with Steven Bochco on the screenplay for Silent Running (1972). According to producer Barry Spikings, Cimino said that he wanted to work again with Washburn.[10] According to Deeley, he only heard from an office rumor that Washburn was contracted by Cimino to work on the script. "Whether Cimino hired Washburn as his sub-contractor or as a co-writer was constantly being obfuscated," wrote Deeley, "and there were some harsh words between them later on, or so I was told."[25]

Cimino's claim

editAccording to Cimino, he would call Washburn while on the road scouting for locations and feed him notes on dialogue and story. Upon reviewing Washburn's draft, Cimino said, "I came back and read it and I just could not believe what I read. It was like it was written by somebody who was ... mentally deranged." Cimino confronted Washburn at the Sunset Marquis in LA about the draft, and Washburn supposedly replied that he couldn't take the pressure and had to go home. Cimino then fired Washburn. Cimino later claimed to have written the entire screenplay himself.[11] Washburn's response to Cimino's comments was, "It's all nonsense. It's lies. I didn't have a single drink the entire time I was working on the script."[10]

Washburn's claim

editAccording to Washburn, he and Cimino spent three days together in Los Angeles at the Sunset Marquis, hammering out the plot. The script eventually went through several drafts, evolving into a story with three distinct acts. Washburn did not interview any veterans to write The Deer Hunter; nor did he do any research. "I had a month, that was it," he explains. "The clock was ticking. Write the fucking script! But all I had to do was watch TV. Those combat cameramen in Vietnam were out there in the field with the guys. I mean, they had stuff that you wouldn't dream of seeing about Iraq." When Washburn was finished, he says, Cimino and Joann Carelli, an associate producer on The Deer Hunter who went on to produce two more of Cimino's later films, took him to dinner at a cheap restaurant off the Sunset Strip. He recalls, "We finished, and Joann looks at me across the table, and she says, 'Well, Deric, it's fuck-off time.' I was fired. It was a classic case: you get a dummy, get him to write the goddamn thing, tell him to go fuck himself, put your name on the thing, and he'll go away. I was so tired, I didn't care. I'd been working 20 hours a day for a month. I got on the plane the next day, and I went back to Manhattan and my carpenter job."[10]

Deeley's reaction to the revised script

editDeeley felt the revised script, now called The Deer Hunter, broke fresh ground for the project. The protagonist in the Redeker/Garfinkle script, Merle, was an individual who sustained a bad injury in active service and was damaged psychologically by his violent experiences, but was nevertheless a tough character with strong nerves and guts. Cimino and Washburn's revised script distilled the three aspects of Merle's personality and separated them out into three distinct characters. They became three old friends who grew up in the same small industrial town and worked in the same steel mill, and in due course were drafted together to Vietnam.[26] In the original script, the roles of Merle (later renamed Mike) and Nick were reversed in the last half of the film. Nick returns home to Linda, while Mike remains in Vietnam, sends money home to help Steven, and meets his tragic fate at the Russian roulette table.[27]

A Writers' Guild arbitration process awarded Washburn sole "Screenplay by" credit.[10] Garfinkle and Redeker were given a shared "Story by" credit with Cimino and Washburn. Deeley felt the story credits for Garfinkle and Redeker "did them less than justice."[25] Cimino contested the results of the arbitration. "In their Nazi wisdom," added Cimino, "[they] didn't give me the credit because I would be producer, director and writer."[28] All four writers—Cimino, Washburn, Garfinkle, and Redeker—received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay for the film.[29]

Filming

editThe Deer Hunter began principal photography on June 20, 1977.[10] It was the first feature film depicting the Vietnam War to be filmed in Thailand. All scenes were shot on location (no sound stages). "There was discussion about shooting the film on a back lot, but the material demanded more realism," says Spikings.[10] The cast and crew watched large amounts of news footage from the war to ensure authenticity. The film was shot over six months. The scenes of the Clairton, Pennsylvania comprise footage shot in eight different towns in three states: West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.[30][10] The film's initial budget was $8.5 million.[21]

Meryl Streep accepted the role of the "vague, stock girlfriend" to remain for the duration of filming with John Cazale, who had been diagnosed with lung cancer.[31] De Niro had spotted Streep in her stage production of The Cherry Orchard and suggested she play his girlfriend Linda.[32] Meryl Streep wrote all of her lines.[33] Streep is said to have accepted the role, primarily, to be with Cazale.[34]

Before the beginning of principal photography, Deeley met with the film's appointed line producer, Robert Relyea, whom Deeley hired after meeting him on the set of Bullitt (1968) and being impressed with his experience. However, Relyea declined the job, refusing to disclose his reason why.[21] Deeley suspected that Relyea sensed in director Cimino something that would have made production difficult. As a result, Cimino was acting without the day-to-day supervision of a producer.[35]

Because Deeley was busy overseeing the production of Sam Peckinpah's Convoy (1978), he hired John Peverall to oversee Cimino's shoot. Peverall's expertise with budgeting and scheduling made him a natural successor to Relyea, and Peverall knew enough about the picture to be elevated to producer status. "John is a straightforward Cornishman who had worked his way up to become a production supervisor," wrote Deeley, "and we employed him as EMI's watchman on certain pictures."[35]

The wedding scenes

editThe wedding scenes were filmed at historic St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral in the Tremont neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio.[36][10] They took five days to film. St. Theodosius' Father Stephen Kopestonsky was cast as the priest.[22] The reception scene was filmed at nearby Lemko Association[37] Hall. The amateur extras cast for the crowded wedding-dance sequences drank real liquor and beer.[38] The scenes were filmed in the summer, in 95 °F (35 °C) weather,[39] but were set in the fall.[22] To accomplish a fall look, individual leaves were removed from deciduous trees.[39][40][41] Zsigmond also had to desaturate the colors of the exterior shots, partly in camera and partly in laboratory processing.[41][42]

The production manager asked each of the extras portraying Russian immigrants to bring to the location a gift-wrapped box to double for wedding presents. The manager figured that if the extras did this, not only would the production save time and money, but the gifts would look more authentic. Once the unit unwrapped and the extras disappeared, the crew discovered to their amusement that the boxes weren't empty but filled with real presents, from china to silverware. "Who got to keep all these wonderful offerings," wrote Deeley, "is a mystery I never quite fathomed."[38]

Cimino originally claimed that the wedding scene would take up 21 minutes of screen time; in the end, it took 51 minutes. Deeley believes that Cimino always planned to make this prologue last for an hour, and "the plan was to be advanced by stealth rather than straight dealing."[43]

At this point in the production, nearly halfway through principal photography, Cimino was already over-budget, and producer Spikings could tell from the script that shooting the extended scene could sink the project.[10]

The bar and the steel mill

editThe bar was specially constructed in an empty storefront in Mingo Junction, Ohio for $25,000; it later became an actual saloon for local steel mill workers.[22] U.S. Steel allowed filming inside its Cleveland mill, including placing the actors around the furnace floor, only after securing a $5 million insurance policy.[16][22] Other filming took place in Pittsburgh.[44]

Hunting the deer

editThe first deer to be shot was depicted in a "gruesome close-up", although he was hit only with a tranquilizer dart.[38][43] This was not a whitetail buck, which is native to Pennsylvania, but a red deer native to Eurasia. The stag that Michael lets escape was the same one later used on TV commercials for The Hartford.[38]

Vietnam and the Russian roulette scenes

editThe Viet Cong Russian roulette scenes were shot with real rats and mosquitoes, as the three principals (De Niro, Walken, and Savage) were tied up in bamboo cages erected along the River Kwai. The woman who was given the task of casting extras in Thailand had much difficulty finding a local to play the vicious-looking individual who runs the game. The first actor hired turned out to be incapable of slapping De Niro in the face. The casting agent then found a local Thai man, Somsak Sengvilai, who held a particular dislike of Americans, and so cast him. De Niro suggested that Walken be slapped by one of the guards without any warning, and Walken's reaction was genuine. Producer Deeley has said that Cimino shot the brutal Vietcong Russian roulette scenes brilliantly and more efficiently than any other part of the film.[38][45]

De Niro and Savage performed their own stunts in the fall into the river, filming the 30 feet (9.1 m) drop 15 times in two days. During the helicopter stunt, the skids caught on the rope bridge as the helicopter rose, threatening to seriously injure De Niro and Savage. The actors gestured and shouted to the crew in the helicopter to warn them. Footage of this is included in the film.[46]

According to Cimino, De Niro requested a live cartridge in the revolver for the scene in which he subjects John Cazale's character to an impromptu game of Russian roulette, to heighten the intensity of the situation. Cazale agreed without protest,[11] but obsessively rechecked the gun before each take to be sure that the live round was not in the next chamber.[22]

While appearing later in the film, the first scenes shot on arrival in Thailand were the hospital sequences between Walken and the military doctor. Deeley believed that this scene was "the spur that would earn him an Academy Award".[47][b]

In the final scene in the gambling den between Mike and Nick, Cimino had Walken and De Niro improvise in one take. His direction to his actors: "You put the gun to your head, Chris, you shoot, you fall over and Bobby cradles your head."[41]

Filming locations

editThailand

- Patpong, Bangkok, the area used to represent Saigon's red light district.[49]

- Sai Yok, Kanchanaburi Province[50]

- River Kwai, prison camp and initial Russian roulette scene.[51]

US

- St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral, in the Tremont neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio. The name plaque is clearly visible in one scene.[52]

- Lemko Association[37] Hall,[53] Cleveland, Ohio. Also located in Tremont, the wedding banquet was filmed here. The name is clearly visible in one scene.[54]

- U.S. Steel Central Furnaces in Cleveland, Ohio. Opening sequence steel mill scenes.[52]

- Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest and Nooksack Falls in the North Cascades range of Washington, deer hunting scenes.[55][56]

Also North Cascades Highway (SR 20), Diablo Lake - Steubenville, Ohio, for some mill and neighborhood shots.[57]

- Struthers, Ohio, for external house and long-range road shots. Also including, the town's bowling alley is the Bowladrome Lanes, located at 56 State Street, Struthers, Ohio.[58][59]

- Weirton, West Virginia, for mill and trailer shots.[60]

Post-production

editBy this point, The Deer Hunter had cost $13 million and the film still had to go through an arduous post-production.[42] Film editor Peter Zinner was given 600,000 feet (110 mi; 180 km) of printed film to edit, a monumental task at the time.[61] Producers Spikings and Deeley were pleased with the first cut, which ran for three and a half hours. "We were thrilled by what we saw," wrote Deeley, "and knew that within the three and a half hours we watched there was a riveting film."[62]

Executives from Universal, including Lew Wasserman and Sid Sheinberg, were not very enthusiastic.[10][62] "I think they were shocked," recalled Spikings. "What really upset them was 'God Bless America'. Sheinberg thought it was anti-American. He was vehement. He said something like 'You're poking a stick in the eye of America.' They really didn't like the movie. And they certainly didn't like it at three hours and two minutes."[10] Deeley was not surprised by the Universal response: "The Deer Hunter was a United Artists sort of picture, whereas Convoy was more in the style of Universal. I'd muddled and sold the wrong picture to each studio."[62] Deeley did agree with Universal that the film needed to be shorter, not just because of pacing but also to ensure commercial success.[63] "A picture under two and a half hours can scrape three shows a day," wrote Deeley, "but at three hours you've lost one third of your screenings and one third of your income for the cinemas, distributors, and profit participants."[63]

Universal president Thom Mount said: "This was just a... continuing nightmare from the day Michael finished the picture to the day we released it. That was simply because he was wedded to everything he shot. The movie was endless. It was The Deer Hunter and the Hunter and the Hunter. The wedding sequence was a cinematic event all unto its own."[10] Mount says he turned to Verna Fields, Universal's head of post-production. "I sicced[clarification needed] Verna on Cimino," Mount says. "Verna was no slouch. She started to turn the heat up on Michael, and he started screeching and yelling."[10]

Zinner eventually cut the film to 18,000 feet (3.4 mi; 5.5 km).[61] Cimino later fired Zinner when he discovered that Zinner was editing the wedding scenes.[40][64] Zinner eventually won the Best Editing Oscar for The Deer Hunter. Regarding his clashes with Cimino, Zinner stated: "Michael Cimino and I had our differences at the end, but he kissed me when we both got Academy Awards."[61] Cimino later commented in The New York Observer, "[Zinner] was a moron ... I cut Deer Hunter myself."[28]

Sound design

editThe Deer Hunter was Cimino's first film to use the Dolby noise-reduction system. "What Dolby does," replied Cimino, "is to give you the ability to create a density of detail of sound—a richness so you can demolish the wall separating the viewer from the film. You can come close to demolishing the screen." It took five months to mix the soundtrack. One short battle sequence—200 feet of film in the final cut—took five days to dub. Another sequence recreated the 1975 American evacuation of Saigon; Cimino brought the film's composer, Stanley Myers, out to the location to listen to the auto, tank, and jeep horns as the sequence was being photographed. The result, according to Cimino: Myers composed the music for that scene in the same key as the horn sounds, so the music and the sound effects would blend with the images to create one jarring, desolate experience.[65]

Previews

editBoth the long and short versions were previewed to Midwestern audiences, although there are differing accounts among Cimino, Deeley, and Spikings as to how the previews panned out.[10] Director Cimino claims he bribed the projectionist to interrupt the shorter version, in order to obtain better reviews of the longer one.[11] According to producer Spikings, Wasserman let EMI's CEO Bernard Delfont decide between the two and chose Cimino's longer cut.[10] Deeley claims that the two-and-a-half-hour version tested had a better response.[66]

Soundtrack

edit| The Deer Hunter | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1990 |

| Recorded | 1978 |

| Genre | Film score |

| Label | Capitol |

The soundtrack to The Deer Hunter was released on audio CD on October 25, 1990.[67]

Selected tracks

edit- Stanley Myers' "Cavatina" (also known as "He Was Beautiful"), performed by classical guitarist John Williams, is commonly known as "The Theme from The Deer Hunter". According to producer Deeley, he discovered that the piece was originally written for a film called The Walking Stick (1970) and, as a result, had to pay the original purchaser an undisclosed sum.[68]

- "Can't Take My Eyes Off You", a 1967 hit song, sung by Frankie Valli.[c] It is played in John's bar when all of the friends sing along and at the wedding reception. According to Cimino, the actors sang along to a recording of the song as it was played instead of singing to a beat track, a standard filmmaking practice. Cimino felt that would make the sing-along seem more real.[22]

- During the wedding ceremonies and party, the Russian Orthodox songs such as "Slava", and Russian folk songs such as "Korobushka" and "Katyusha", are played.

- The final passage from Kamarinskaya by Mikhail Glinka is heard briefly when the men are driving through the mountains. Also, a part of the opening section of the same work is heard during the second hunt when Michael is about to shoot the stag.

- Russian Orthodox funeral music is also employed during Nick's funeral scene, mainly "Vechnaya Pamyat", which means "eternal memory".[69]

Theatrical release

editThe producer Allan Carr took over its marketing and convinced the studio to allow the film to be played on the Z Channel before theatrical release.[70]

The Deer Hunter debuted at one theater each in New York and Los Angeles for a week on December 8, 1978.[10][71] The release strategy was to qualify the film for Oscar consideration and close after a week to build interest.[72][70]

After the Oscar nominations, Universal widened the distribution to include major cities, building up to a full-scale release on February 23, 1979, just following the Oscars.[72] This film pioneered a new release pattern for so-called prestige pictures that screen only at the end of the year to qualify for Academy Award recognition.[73] The film eventually grossed $48.9 million at the US box office.[2]

CBS paid $3.5 million for three runs of the film. The network later cancelled the acquisition on the contractually permitted grounds of the film containing too much violence for US network transmission,[74] the Russian Roulette scene was deemed controversial.[70]

Home media

editThe Deer Hunter has twice been released on DVD in America. The first 1998 issue was by Universal, with no extra features and a non-anamorphic transfer, and has since been discontinued.[75] A second version, part of the "Legacy Series", was released as a two-disc set on September 6, 2005, with an anamorphic transfer of the film. The set features a cinematographer's commentary by Vilmos Zsigmond, deleted and extended scenes, and production notes.[76]

The Region 2 version of The Deer Hunter, released in the UK and Japan, features a commentary track from director Michael Cimino.[77]

The film was released on HD DVD on December 26, 2006.[78]

StudioCanal released the film on the Blu-ray format in countries other than the United States on March 11, 2009.[79] It was released on Blu-ray in the U.S. on March 6, 2012.[80]

On May 26, 2020, Shout! Factory released the film on Ultra HD Blu-ray featuring a new Dolby Vision transfer.[81]

Analysis

editControversy over Russian roulette

editOne of the most talked-about sequences in the film, the Viet Cong's use of Russian roulette with POWs, was criticized as being contrived and unrealistic since there were no documented cases of Russian roulette in the Vietnam War.[10][82][83] Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the war, wrote in the Los Angeles Times, "In its 20 years of war, there was not a single recorded case of Russian roulette ... The central metaphor of the movie is simply a bloody lie."[10]

Cimino countered that his film was not political, polemical, literally accurate, or posturing for any particular point of view.[82] Nevertheless, he also claimed he had news clippings from Singapore that confirm Russian roulette was used during the war, without specifying which article.[11]

Critics' response

editIn his review, Roger Ebert defended the artistic license of Russian roulette, arguing "it is the organizing symbol of the film: Anything you can believe about the game, about its deliberately random violence, about how it touches the sanity of men forced to play it, will apply to the war as a whole. It is a brilliant symbol because, in the context of this story, it makes any ideological statement about the war superfluous."[84]

Film critic and biographer David Thomson also agrees that the film works despite the controversy: "There were complaints that the North Vietnamese had not employed Russian roulette. It was said that the scenes in Saigon were fanciful or imagined. It was also suggested that De Niro, Christopher Walken, and John Savage were too old to have enlisted for Vietnam (Savage, the youngest of the three, was thirty). Three decades later [written in 2008], 'imagination' seems to have stilled those worries ... and The Deer Hunter is one of the great American films."[85]

In her review, Pauline Kael wrote "The Vietcong are treated in the standard inscrutable-evil Oriental style of the Japanese in the Second World War movies ... The impression a viewer gets is that if we did some bad things there we did them ruthlessly but impersonally; the Vietcong were cruel and sadistic."[10]

In his Vanity Fair article "The Vietnam Oscars", Peter Biskind wrote that the political agenda of The Deer Hunter was something of a mystery: "It may have been more a by-product of Hollywood myopia, the demands of the war-film genre, garden-variety American parochialism, and simple ignorance than it was the pre-meditated right-wing road map it seemed to many."[10]

Cast and crew response

editAccording to Christopher Walken, the historical context was not paramount: "In the making of it, I don't remember anyone ever mentioning Vietnam!" De Niro added to this sentiment: "Whether [the film's vision of the war] actually happened or not, it's something you could imagine very easily happening. Maybe it did. I don't know. All's fair in love and war." Producer Spikings, while proud of the film, regrets the way the Vietnamese were portrayed. "I don't think any of us meant it to be exploitive," Spikings said. "But I think we were ... ignorant. I can't think of a better word for it. I didn't realize how badly we'd behaved to the Vietnamese people ..."[10]

Producer Deeley, on the other hand, was quick to defend Cimino's comments on the nature and motives of the film: "The Deer Hunter wasn't really 'about' Vietnam. It was something very different. It wasn't about drugs or the collapse of the morale of the soldiers. It was about how individuals respond to pressure: different men reacting quite differently. The film was about three steel workers in extraordinary circumstances. Apocalypse Now is surreal. The Deer Hunter is a parable ... Men who fight and lose an unworthy war ,face some obvious and unpalatable choices. They can blame their leaders.. or they can blame themselves. Self-blame has been a great burden for many war veterans. So how does a soldier come to terms with his defeat and yet still retain his self-respect? One way is to present the conquering enemy as so inhuman, and the battle between the good guys (us) and the bad guys (them) so uneven, as to render defeat irrelevant. Inhumanity was the theme of The Deer Hunter's portrayal of the North Vietnamese prison guards forcing American POWs to play Russian roulette. The audience's sympathy with prisoners who (quite understandably) cracked thus completes the chain. Accordingly, some veterans who suffered in that war found the Russian roulette a valid allegory."[86]

Director Cimino's autobiographical intent

editCimino frequently referred to The Deer Hunter as a "personal" and "autobiographical" film, although later investigation by journalists like Tom Buckley of Harper's revealed inaccuracies in Cimino's accounts and reported background.[87]

Male friendship

editAFI Movie Club// says "the film portrays male friendship in an atypical way for the time" and asks: "how does the friendship of the characters played by Robert De Niro, John Savage, Christopher Walken and John Cazale evolve throughout the film?"[70]

Coda of "God Bless America"

editThe final scene in which all the main characters gather and sing "God Bless America" became a subject of heated debate among critics when the film was released. It raised the question of whether this conclusion was meant ironically or not – "as a critique of patriotism or a paean to it".[10] Cimino later spoke of his intentions for the scene:

"The ending is really, not meant to be so much a statement of patriotism, but a statement of communion. When people are in trouble, as they are when they're very troubled and sick inside, spiritually very sick, they need, sometimes to do something together. In this case it's make a sound. And they sing that song because it's a song that every American child knows by heart, because you're taught it in school. Everybody knows the words of "God Bless America", and so it's a communal sound, and they begin to sing the one song they all know from grade school on. And you never forget those words as long as you live. And so they sing... the one song they happen to know happens to be "God Bless America", and it reunites them as a family. It becomes a family communion. Instead of a Last Supper, it becomes a first breakfast, if you will, of a new family. It is breakfast that they're eating. It's not the Last Supper, it's the first breakfast."[88]

Reception

editCritical response

editUpon its release, The Deer Hunter received acclaim from critics, who considered it the best American epic since Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather.[48][87][89] The film was praised for its depiction of realistic working-class settings and environment; Cimino's direction; the performances of De Niro, Walken, Streep, Savage, Dzundza and Cazale; the symphonic shifts of tone and pacing in moving from America to Vietnam; the tension during the Russian roulette scenes; and the themes of American disillusionment.[90] The film holds an approval rating of 86% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 132 reviews, with an average score of 8.60/10. The consensus reads: "Its greatness is blunted by its length and one-sided point of view, but the film's weaknesses are overpowered by Michael Cimino's sympathetic direction and a series of heartbreaking performances from Robert De Niro, Meryl Streep, and Christopher Walken".[91] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 90 out of 100 based on reviews from 18 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[92]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars and called it "one of the most emotionally shattering films ever made."[84] Gene Siskel from the Chicago Tribune praised the film, saying, "This is a big film, dealing with big issues, made on a grand scale. Much of it, including some casting decisions, suggest inspiration by The Godfather."[93] Leonard Maltin also gave the film four stars, calling it a "sensitive, painful, evocative work".[94] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called The Deer Hunter "a big, awkward, crazily ambitious motion picture that comes as close to being a popular epic as any movie about this country since The Godfather. Its vision is that of an original, major new filmmaker."[89] David Denby of New York called it "an epic" with "qualities that we almost never see any more—range and power and breadth of experience."[95][96] Jack Kroll of Time asserted it put director Cimino "right at the center of film culture."[96] Stephen Farber pronounced the film in New West magazine as "the greatest anti-war movie since La Grande Illusion."[96]

However, The Deer Hunter was not without critical backlash. Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote a positive review with some reservations: "[It is] a small minded film with greatness in it ... with an enraptured view of common life ... [but] enraging, because, despite its ambitiousness and scale, it has no more moral intelligence than the Eastwood action pictures."[96] William Goldman, in his book Adventures in the Screen Trade, described The Deer Hunter as a "well-disguised comic-book movie". He wrote, "I enjoyed it every bit as I used to be enthralled by Batman having it out with the Penguin — and precisely on that level."[97]

Andrew Sarris wrote that the film was "massively vague, tediously elliptical, and mysteriously hysterical ... It is perhaps significant that the actors remain more interesting than the characters they play."[10] Jonathan Rosenbaum disparaged The Deer Hunter as an "Oscar-laden weepie about macho buddies" and "a disgusting account of what the evil Vietnamese did to poor, innocent Americans".[98] John Simon of New York wrote: "For all its pretensions to something newer and better, this film is only an extension of the old Hollywood war-movie lie. The enemy is still bestial and stupid, and no match for our purity and heroism; only we no longer wipe up the floor with him—rather, we litter it with his guts."[99] In a review of The Deer Hunter for Chicago magazine, Studs Terkel wrote that he was "appalled by its shameless dishonesty," and that "not since The Birth of a Nation has a non-Caucasian people been portrayed in so barbaric a fashion." Cimino's dishonesty "was to project a sadistic psyche not only onto 'Charlie' but to all the Vietnamese portrayed."[100]

Author Karina Longworth notes that Streep "made a case for female empowerment by playing a woman to whom empowerment was a foreign concept—a normal lady from an average American small town, for whom subservience was the only thing she knew".[101] She states that The Deer Hunter "evokes a version of dominant masculinity in which male friendship is a powerful force". It has a "credibly humanist message", and that the "slow study of the men in blissfully ignorant homeland machismo is crucial to it".[32]

Despite its critical acclaim and awards, some critics derided what they considered the film's simplistic, bigoted, and historically inaccurate depictions of the Viet Cong and America's position in the Vietnam War.[102] The central theme of the Viet Cong forcing American captives to play Russian roulette has been widely criticized as having no historical basis, a claim Cimino denied but did not refute with evidence.[citation needed]

During the 29th Berlin International Film Festival in 1979, the Soviet delegation expressed its indignation with the film which, in their opinion, insulted the Vietnamese people in numerous scenes.[103] Other communist states also voiced their solidarity with the "heroic people of Vietnam". They protested against the screening of the film and insisted that it violated the statutes of the festival because it in no way contributed to the "improvement of mutual understanding between the peoples of the world". The ensuing domino effect led to the walk-outs of the Cubans, East Germans, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Poles and Czechoslovakians, and two members of the jury resigned in sympathy.[104]

Top-ten lists

edit- 3rd—Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times.[105] Ebert also placed Deer Hunter on his list of the best films of the 1970s.[106]

- 3rd—Gene Siskel, Chicago Tribune[107]

Academy Award-winning film director Miloš Forman and Academy Award-nominated actor Mickey Rourke consider The Deer Hunter to be one of the greatest films of all time.[108][109]

Revisionism following Heaven's Gate

editCimino's next film, Heaven's Gate (1980), debuted to lacerating reviews and took in only $3 million in ticket sales, effectively leaving United Artists bankrupt. The failure of Heaven's Gate led several critics to revise their positions on The Deer Hunter. Canby said in his famous review of Heaven's Gate, "[The film] fails so completely that you might suspect Mr. Cimino sold his soul to the Devil to obtain the success of The Deer Hunter, and the Devil has just come around to collect."[110] Andrew Sarris wrote in his review of Heaven's Gate, "I'm a little surprised that many of the same critics who lionized Cimino for The Deer Hunter have now thrown him to the wolves with equal enthusiasm."[111] Sarris added, "I was never taken in ... Hence, the stupidity and incoherence in Heaven's Gate came as no surprise since very much the same stupidity and incoherence had been amply evident in The Deer Hunter."[111] In his book Final Cut: Dreams and Disaster in the Making of Heaven's Gate, Steven Bach wrote, "critics seemed to feel obliged to go on the record about The Deer Hunter, to demonstrate that their critical credentials were un-besmirched by having been, as Andrew Sarris put it, 'taken in.'"[111] Film critic Mark Kermode described Deer Hunter as "a genuinely terrible film".[112]

However, many critics, including David Thomson[90] and A. O. Scott,[113] maintain that The Deer Hunter is still a great film, the power of which has not diminished.

Awards

edit| Academy Awards record | |

|---|---|

| 1. Best Actor in a Supporting Role, Christopher Walken | |

| 2. Best Director, Michael Cimino | |

| 3. Best Film Editing, Peter Zinner | |

| 4. Best Picture, Barry Spikings, Michael Deeley, Michael Cimino, John Peverall | |

| 5. Best Sound, Richard Portman, William L. McCaughey, Aaron Rochin, C. Darin Knight | |

| Golden Globe Awards record | |

| 1. Best Director – Motion Picture, Michael Cimino | |

| BAFTA Awards record | |

| 1. Best Film Cinematography, Vilmos Zsigmond | |

| 2. Best Film Editing, Peter Zinner | |

Lead-up to awards season

editFilm producer and "old-fashioned mogul" Allan Carr used his networking abilities to promote The Deer Hunter. "Exactly how Allan Carr came into The Deer Hunter's orbit I can no longer remember," recalled producer Deeley, "but the picture became a crusade to him. He nagged, charmed, threw parties, he created word-of-mouth – everything that could be done in Hollywood to promote a project. Because he had no apparent motive for this promotion, it had an added power and legitimacy and it finally did start to penetrate the minds of the Universal's sales people that they actually had in their hands something a bit more significant than the usual."[68] Deeley added that Carr's promotion of the film was influential in positioning The Deer Hunter for Oscar nominations.[72]

On the Sneak Previews special "Oscar Preview for 1978", Roger Ebert correctly predicted that The Deer Hunter would win for Best Picture while Gene Siskel predicted that Coming Home would win. However, Ebert incorrectly guessed that Robert De Niro would win for Best Actor for Deer Hunter and Jill Clayburgh would win for Best Actress for An Unmarried Woman while Siskel called the wins for Jon Voight as Best Actor and Jane Fonda as Best Actress, both for Coming Home. Both Ebert and Siskel correctly predicted the win for Christopher Walken receiving the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.[48]

According to producer Deeley, orchestrated lobbying against The Deer Hunter was led by Warren Beatty, whose own picture Heaven Can Wait had multiple nominations.[114] Beatty also used ex-girlfriends in his campaign: Julie Christie, serving on the jury at the Berlin Film Festival where Deer Hunter was screened, joined the walkout of the film by the Russian jury members. Jane Fonda also criticized The Deer Hunter in public. Deeley suggested that her criticisms partly stemmed from the competition between her film Coming Home vying with The Deer Hunter for Best Picture. According to Deeley, he planted a friend of his in the Oscar press area behind the stage to ask Fonda if she had seen The Deer Hunter.[64] Fonda replied she had not seen the film, and to this day she still has not.[10][64]

As the Oscars drew near, the backlash against The Deer Hunter gathered strength. When the limos pulled up to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on April 9, 1979, they were met by demonstrators, mostly from the Los Angeles chapter of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. The demonstrators waved placards covered with slogans that read "No Oscars for racism" and "The Deer Hunter a bloody lie" and thrust pamphlets berating Deer Hunter into long lines of limousine windows.[10][64] Washburn, nominated for Best Original Screenplay, claims his limousine was pelted with stones. According to Variety, "Police and The Deer Hunter protesters clashed in a brief but bloody battle that resulted in 13 arrests."[10]

De Niro was so anxious that he did not attend the Oscars ceremony. He asked the Academy to allow him to sit out the show backstage, but when the Academy refused, De Niro stayed home in New York.[115] Producer Deeley made a deal with fellow producer David Puttnam, whose film Midnight Express was nominated, that each would take $500 to the ceremony so if one of them won, the winner would give the loser the $500 to "drown his sorrows in style."[114]

Complete list of awards

editLegacy

editThe Deer Hunter was among the early, and most controversial, major theatrical films to be critical of the American involvement in Vietnam following 1975 when the war officially ended. While the film opened the same year as Hal Ashby's Coming Home, Sidney Furie's The Boys in Company C, and Ted Post's Go Tell the Spartans, it was the first film about Vietnam to reach a wide audience and critical acclaim, culminating in the winning of the Oscar for Best Picture. Other films released later that illustrated the 'hellish', futile conditions of bloody Vietnam War combat included:[82]

- Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979)

- Oliver Stone's Platoon (1986)

- Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket (1987)

- Brian De Palma's Casualties of War (1989)

- Oliver Stone's Born on the Fourth of July (1989)

David Thomson wrote in an article titled "The Deer Hunter: Story of a scene" that the film changed the way war-time battles were portrayed on film: "The terror and the blast of firepower changed the war film, even if it only used a revolver. More or less before the late 1970s, the movies had lived by a Second World War code in which battle scenes might be fierce but always rigorously controlled. The Deer Hunter unleashed a new, raw dynamic in combat and action, paving the way for Platoon, Saving Private Ryan and Clint Eastwood's Iwo Jima films."[122]

In a 2011 interview with Rotten Tomatoes, actor William Fichtner retrospectively stated that he and his partner were silenced after seeing the film, stating that "the human experience was just so pointed; their journeys were so difficult, as life is sometimes. I remember after seeing it, walking down the street — I actually went with a girl on a date and saw The Deer Hunter, and we left the theater and walked for like an hour and nobody said anything; we were just kind of stunned about that."[123]

The deaths of approximately 25 people who died playing Russian roulette were reported as having been influenced by scenes in the movie.[124]

Honors and recognition

editIn 1996, The Deer Hunter was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[119]

American Film Institute included the film as #79 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies,[125] #30 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills,[126] and #53 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition).[127]

The film ranks 467th in the Empire magazine's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time,[128] noting:

Cimino's bold, powerful 'Nam epic goes from blue-collar macho rituals to a fiery, South East Asian hell and back to a ragged singalong of America the Beautiful [sic]. De Niro holds it together, but Christopher Walken, Meryl Streep and John Savage are unforgettable.[128]

The New York Times placed the film on its Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[129]

Jan Scruggs, a Vietnam veteran who became a counselor with the U.S. Department of Labor, thought of the idea of building a National Memorial for Viet Nam Veterans after seeing a screening of the film in March 1979, and he established and operated the memorial fund which paid for it.[130] Director Cimino was invited to the memorial's opening.[11]

See also

edit- The Deer Hunter (novel) (1978)

- The Last Hunter (1980), an Italian film originally made as an unofficial sequel

Notes

edit- ^ The characters' precise ethnic affiliation (i.e. whether they are Russian Americans,[4][5] Ukrainian Americans,[4][5] Rusyn Americans,[5] etc. or any combination thereof) is left open to interpretation.

- ^ A clip from the scene between Walken and the military doctor was shown on a Sneak Previews special "Oscar Preview for 1978," in which critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert correctly predicted that Walken would win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.[48]

- ^ While featured prominently in the film, "Can't Take My Eyes Off You" does not appear on The Deer Hunter's soundtrack.[67]

- ^ Tied with An Unmarried Woman

References

edit- ^ a b "THE DEER HUNTER (X)". British Board of Film Classification. November 15, 1978. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Deer Hunter (1978)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b George Morris, "Ready, Aim... Click", Texas Monthly, Vol. 7, No. 3 (March 1979), page 142: "The film attempts to portray the effect of the Vietnam war on three Slavic American steelworkers from a small town in Pennsylvania who volunteer for the war."

- ^ a b c Sylvia Shin Huey Chong, "Restaging the War: 'The Deer Hunter' and the Primal Scene of Violence"[dead link] (PDF at Academia.edu), Cinema Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Winter, 2005), p. 103: "It is interesting to contrast Nguyen's narrative of failed assimilation with The Deer Hunter's consolidation of white ethnics (Russian or Ukrainian Americans) into the American body politic through their participation in the Vietnam War."

- ^ a b c d Steven Biel, "The Deer Hunter Debate", Bright Lights Film Journal (ISSN 0147-4049), July 7, 2016: "The first sixty-eight minutes of the three-hour film establish their friendships within Clairton's traditional, patriotic Russian Orthodox community. (The characters' ethnicity isn't actually specified in the screenplay. Viewers have variously identified them as Russian, Slovak, Carpatho-Russian, Ukrainian, Rusyn, Polish, and Belarusian. Pittsburgh native Andy Warhol, who saw a preview of the film in New York in late November 1978, wrote in his diary that the movie's setting was 'where all my cousins are from' and 'was really Czechoslovakian.')"

- ^ Stern, Christopher (December 2, 1996). "National Film Registry taps 25 more pix". Variety. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Robert de Niro : l'interview "1ère fois" de Thierry Ardisson / Archive INA on YouTube, Double Jeu, Antenne 2, May 2, 1992.

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 168

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Biskind, Peter (February 19, 2008). "The Vietnam Oscars". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Realizing The Deer Hunter: An Interview with Michael Cimino. Blue Underground. Interview on The Deer Hunter UK Region 2 DVD and the StudioCanal Blu-Ray. First half of video on YouTube

- ^ De Niro, Robert (actor) (June 12, 2003). AFI Life Achievement Award: A Tribute to Robert De Niro. [Television Production] American Film Institute.

- ^ a b Parker, p. 129

- ^ "Richard Shepard Talks John Cazale Doc, Plus The Trailer For 'I Knew It Was You'". The Playlist. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ Swerling, Gabriella (December 7, 2019). "De Niro saved the Deer Hunter by paying for co-star's medical insurance when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Parker, p. 128

- ^ "Chuck Aspegren". Getty Images. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Addison, Paul. "Chuck Aspegren (Deceased), Hobart, IN Indiana". Hobart Alumni .org. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Deeley, p. 167

- ^ Deeley, p. 170

- ^ a b c Deeley, p. 171

- ^ a b c d e f g DVD commentary by director Michael Cimino and film critic F. X. Feeney. Included on The Deer Hunter UK region 2 DVD release and the StudioCanal Blu-ray.

- ^ a b c Deeley, p. 2

- ^ a b c Deeley, p. 163

- ^ a b c d Deeley, p. 164

- ^ Deeley, p. 166

- ^ Washburn, Deric. "The Deer Hunter script". DailyScript.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Griffin, Nancy (February 10, 2002). "Last Typhoon Cimino Is Back". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "The 51st Academy Awards - 1979". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter (1978)". Movie Locations. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

The town, however, is an amalgamation of eight separate locales. Three are in Pennsylvania...Clairton; McKeesport...and Pittsburgh. ...Weirton and Follansbee, in...West Virginia. And...in Ohio State: Steubenville and Mingo Junction...and Struthers...

- ^ Longworth 2013, pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Longworth 2013, p. 21.

- ^ "Meryl Streep Guest of honour at the opening ceremony of the 77th Festival de Cannes". FloridaNationalNews.com. May 17, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ "A heartbreaking loss led Meryl Streep to Don Gummer". honey.nine.com.au. October 22, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 172

- ^ "The Deer Hunter Locations". latlong.net. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "About Us". The Lemko Association. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Deeley, p. 174

- ^ a b Boyle, Janet (July 25, 1977). "Filming of The Deer Hunter: Theaters Pushing for 'Deer' Premiere". Wheeling Intelligencer. Retrieved September 13, 2024 – via archive.wvculture.org.

- ^ a b Shooting The Deer Hunter: An interview with Vilmos Zsigmond. Blue Underground. Interview with the cinematographer, located on The Deer Hunter UK Region 2 DVD and StudioCanal Blu-Ray. First half of video on YouTube.

- ^ a b c Deeley, p. 177

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 178

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 173

- ^ "City Lands Good Share of Movies". The Vindicator. Youngstown. Associated Press. December 10, 1995. p. B5. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Deeley, p. 175

- ^ Playing The Deer Hunter: An interview with John Savage. Blue Underground. Interview with the actor Savage, located on the UK Region 2 DVD and StudioCanal Blu-Ray. First half of video on YouTube

- ^ Deeley, p. 176

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger & Siskel, Gene (hosts); Flaum, Thea & Solley, Ray (producers); Denny, Patterson (director). (1979). Sneak Previews: Oscar Preview for 1978. [Television Production]. Chicago, IL: WTTW.

- ^ "7 Movie Locations in Bangkok - Bangkok.com Magazine". Bangkok.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Nam, Suzanne (2012). Moon Thailand. Avalon Travel. p. 320. ISBN 9781598809695.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Deer Hunter film locations". The Worldwide Guide To Movie Locations. September 7, 2015. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "ST. THEODOSIUS RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CATHEDRAL". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Rotman, Michael. "Lemko Hall". Cleveland Historical. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ "Lemko Hall". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. May 24, 2002. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Krause, Mariella (2013). Lonely Planet Pacific Northwest's Best Trips. Lonely Planet. p. 118. ISBN 978-1741798159. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter film locations (1978)". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Randy Fox Writer and photographer (May 5, 2012). "'The Deer Hunter' And 'Reckless': Hollywood Briefly Comes To The Factory Valleys (PHOTOS)". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ "History - Struthers, Ohio". Strutherscommunity.weebly.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ "Youngstown News, Bowladrome Lanes owners reflect on 40 years in the business". Vindy.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Sterling, Joe (July 5, 1077). ""Deer Hunter" Filming Under Way". Weirton Daily Times. West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c McLellan, Dennis (November 16, 2007). "Peter Zinner, 88; film editor won Oscar for 'The Deer Hunter'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c Deeley, p. 179

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 192

- ^ a b c d Deeley, p. 4

- ^ Schreger, Charles (April 15, 1985). "Altman, Dolby, and the Second Sound Revolution". In Belton, John; Weis, Elisabeth (eds.). Film Sound: Theory and Practice (Paperback ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-231-05637-0.

- ^ Deeley, p. 193

- ^ a b "The Deer Hunter: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack" Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Amazon.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 195

- ^ "An Eastern Orthodox Approach to the Brothers Karamazov by Donald Sheehan" Archived September 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Dartmouth.edu. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "AFI Movie Club: THE DEER HUNTER". American Film Institute. September 13, 2024. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Bach, p. 166

- ^ a b c Deeley, p. 196

- ^ Chaffin-Quiray, Garrett (writer); Schnider, Steven Jay (general editor) (2003). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (2003 ed.). London, England: Quintet Publishing. p. 642. ISBN 0-7641-5701-9.

- ^ Deeley, p. 181

- ^ "The Deer Hunter (1978)—DVD details" Archived October 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. IMDb. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter (Universal Legacy Series)" Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Amazon.com. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "View topic—The Deer Hunter (DVD vs. BD — Scandinavia) ADDED" Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Rewind Forums. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter HD-DVD" Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Amazon.com. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ "Achetez le Blu-Ray Voyage au bout de l'enfer" (in French). StudioCanal.com. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter Blu-ray" Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Amazon.com. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ^ The Deer Hunter 4K Blu-ray Release Date May 26, 2020, archived from the original on June 4, 2020, retrieved May 17, 2020

- ^ a b c Dirks, Tim. "The Deer Hunter (1978)" Archived July 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Greatest Films. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ Auster, Albert; Quart, Leonard (2002). "The seventies". American film and society since 1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 120–1. ISBN 978-0-275-96742-0.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (March 9, 1979). "The Deer Hunter". Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

- ^ Thomson, David (October 14, 2008). "Have You Seen ... ?": A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films. New York, NY: Random House. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-307-26461-9.

- ^ Deeley, p. 198

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 197

- ^ "Michael Cimino: I'm probably not so different than Visconti or Ford (2007)". YouTube. August 18, 2022. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ a b Vincent, Canby (December 15, 1978). "Movie Review: The Deer Hunter (1978)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Thomson, David (October 26, 2010). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Fifth Edition, Completely Updated and Expanded (Hardcover ed.). Alfred A. Knopf. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-307-27174-7.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter (1978)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ The Deer Hunter (1978), archived from the original on June 17, 2018, retrieved March 28, 2024

- ^ Siskel, Gene (March 9, 1979). "The Deer Hunter". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (August 2008). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. New York, NY: Penguin Group. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ Bach, p. 167

- ^ a b c d Bach, p. 168

- ^ Goldman, Goldman (1983). Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting. New York: Warner Books. p. 154. ISBN 0446512737.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "The Deer Hunter". The Reader. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ Simon, John (February 16, 1979). New York. Anthologized in the collection Reverse Angle (1982).

- ^ Terkel, Studs (1999). The spectator : talk about movies and plays with the people who make them. New York: The New Press. ISBN 1-56584-553-6. OCLC 40683723. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Longworth 2013, p. 19.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (April 26, 1979). "Oscar-Winning 'Deer Hunter' is Under Attack as 'Racist' Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (March 1, 2024). "The Deer Hunter reviewed: 'more a romantic melodrama than a realist document' – archive, 1979". The Guardian. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "29th Berlin International Film Festival (February 20 - March 3, 1979)". Berlin International Film Festival. Archived from the original on August 21, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 15, 2004). "Ebert's 10 Best Lists: 1967-present". Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (host); Gene (host), Siskel (December 20, 1979). "Sneak Previews: Best Films of the 1970s". Archived from the original on November 6, 2014.

- ^ "Siskel and Ebert Top Ten Lists (1969–1998)". Innermind.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Top Ten Poll 2002—Milos Forman". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010.

- ^ Presentation of the film by Mickey Rourke. Video located on The Deer Hunter Blu-ray.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 19, 1980). "'Heaven's Gate,' A Western by Cimino". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c Bach, p. 370

- ^ "Mark Kermode". Twitter. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Critics' Picks: The Deer Hunter on YouTube by The New York Times film critic A. O. Scott on YouTube.

- ^ a b Deeley, p. 3

- ^ Deeley, p. 1

- ^ "Film in 1980". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "31st Annual DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 1979". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b "Films Selected to The National Film Registry 1989–2008" Archived May 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Library of Congress. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (January 4, 1979). "Critics Cite 'Get Out Your Handkerchiefs'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 21, 1978). "Miss Bergman, Jon Voight And 'Deer Hunter' Cited". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Thomson, David (October 19, 2010). "The Deer Hunter: Story of a scene". The Guardian. Guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ Goodsell, Luke (February 25, 2011). "Five Favorite Films with William Fichtner". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "The Deer Hunter and Suicides". Snopes.com. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies" Archived October 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute. "79. The Deer Hunter 1978". Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Thrills" Archived June 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute. "30. The Deer Hunter 1978". Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "AFI'S 100 Years ... 100 Movies—10th Anniversary Edition" Archived August 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. American Film Institute. "53. The Deer Hunter 1978". Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time" Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Empire. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made. The New York Times via Internet Archive. Published April 29, 2003. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Scruggs, Jan C.; Swerdlow, Joel L. (April 1985). To Heal a Nation: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial. New York, NY: Harpercollins. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-06-015404-2.

Further reading

edit- Bach, Steven (September 1, 1999). Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film That Sank United Artists (Updated 1999 ed.). New York, NY: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-374-4.

- Deeley, Michael (April 7, 2009). Blade Runners, Deer Hunters, & Blowing the Bloody Doors Off: My Life in Cult Movies (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-60598-038-6.

- Kachmar, Diane C. (2002). Roy Scheider: a film biography. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1201-1.

- Longworth, Karina (2013). Meryl Streep: Anatomy of an Actor. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-6669-7.

- Parker, John (2009). Robert De Niro: Portrait of a Legend. London, England: John Blake Publishing ISBN 978-1-84454-639-8.

- McKee, Bruce (1997). Story (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 126, 296-7, 308. ISBN 0-06-039168-5.

- Mitchell, Robert (writer); Magill, Frank N. (editor) (1980). "The Deer Hunter". Magill's Survey of Cinema: A-Eas. 1. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Salem Press pp. 427–431. ISBN 0-89356-226-2.

- Raimondi, Antonio; Raimondi, Rocco. (2021) "Robert De Niro and the Vietnam War". Italy. ISBN 979-8590066575.

External links

editInterviews

- Michael Cimino on 'The Deer Hunter' (1978) #01 on YouTube

- Michael Cimino on 'The Deer Hunter' (1978) #02 on YouTube

Texts

- Original script (PDF) at Scripts.com

- In which Michael is called Merle and stays in Saigon while Nick returns to Linda.

- Film dialogs (English, Spanish, Portuguese) at Kino

Metadata