Taruga is an archeological site in Nigeria famous for the artifacts of the Nok culture that have been discovered there, some dating to 600 BC, and for evidence of very early iron working.[1] The site is 60 km southeast of Abuja, in the Middle Belt.[2]

Background

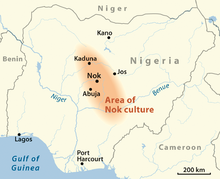

editTaruga is just one of the sites in central Nigeria where artifacts from the Nok culture have been excavated. Since 1945, similar figurines and pottery have been found in many other locations in the area, often uncovered accidentally by modern tin miners, and dating from before 500 BC to 200 AD.[3] The region was probably moister and more heavily wooded during this period than it is today, but was still north of the zone of dense forests. The people would have subsisted by farming and cattle raising. As the climate gradually became drier, they would have drifted south, so the Nok people may have been the ancestors of people such as the Igala, Nupe, Yoruba and Ibo, whose artwork shows similarities to the earlier Nok artifacts.[4]

Clay figurines and pottery

editEarly terracotta figurines from Taruga are decorated with bands of oblique comb stamping, parallel grooving, false relief chevron and incised hatched triangles. These designs appear to have influenced subsequent Ife traditions. Later styles are similar to findings from the Neolithic and Iron Age at Rim in Upper Volta, with decorations such as twisted and carved roulettes.[5] Many of the heads or busts that have been found may once have been part of complete figures.[6] The figurines probably represented tribal heroes and ancestors, and would have been housed in shrines in permanent village compounds.[4]

Pottery is typically decorated with raised dots made by a carved roulette, which may cover most of the body of the pot. Often the dots are combined with grooved lines, and may make a net-like pattern over the body of the pot. Both the figurines and the pottery were baked at low temperature, and are therefore fragile.[3]

Iron working

editBernard Fagg undertook a controlled evacuation of Taruga in the 1960s, finding both terracotta figurines and iron slag with radiocarbon dates from about the fourth and third centuries BC.[4][7] Iron working at the site has now been firmly dated to 600 BC, two hundred years before it began in Katsina-Ala, another Nok center.[8] This is the earliest known date for iron working in Sub-Saharan Africa.[9] It has been speculated that iron smelting technology was introduced to the region from North Africa, perhaps via Meroe, but it may well have developed indigenously, building on earlier copper-smelting technology in which iron ore was used as a flux.[10] The beehive and cylindrical furnaces of West Africa are quite different in form from those of North Africa and Mesopotamia.[11] The iron workers at Taruga certainly seem to have developed the innovation of pre-heating the air entering the furnace so as to obtain higher temperatures.[10]

A short blade found at Taruga dating to around the fourth century BC was probably made from smaller pieces of metal forged together by a "piling" technique. The fragments obtained by smelting would have been wrapped in clay, heated to 1200 °C, then taken from the fire and forged to weld them into a single piece.[12] This approach is sophisticated, since it prevented excessive oxidization during the long period of heating. The metal is extraordinarily free of impurities.[13]

Today

editAs of October 2007, the Federal Government was being asked to protect and rehabilitate the site in view of its tourist potential. However, the site was threatened by illegal miners looking to develop the mineral resources.[14]

References

edit- ^ Toyin Falola, Matthew M. Heaton (2008). A history of Nigeria. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-521-68157-X.

- ^ J. Desmond Clark; J. D.. Fage; Roland Oliver; Richard Gray; John E.. Flint; G. N.. Sanderson; A. D.. Roberts; Michael Crowder. The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 330. ISBN 0-521-21592-7.

- ^ a b Nicole Rupp, James Ameje & Peter Breunig (2005). "NEW STUDIES ON THE NOK CULTURE OF CENTRAL NIGERIA" (PDF). Journal of African Archaeology. 3 (2): 283–290. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ a b c Roland Anthony Oliver, Brian M. Fagan (1975). Africa in the Iron Age, c500 B.C. to A.D. 1400, Part 1400. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-521-09900-5.

- ^ G. Mokhtar (1981). Ancient civilizations of Africa. University of California Press. p. 611. ISBN 0-435-94805-9.

- ^ John Onians (2004). "Africa 500 BC-AD 600". Atlas of world art. Laurence King Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 1-85669-377-5.

- ^ Nicole Rupp, Peter Breunig & Stefanie Kahlheber (June 2008). "Exploring the Nok enigma". Antiquity. 82 (316). Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ^ Elizabeth Allo Isichei (1997). A history of African societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-521-45599-5.

- ^ Muḥammad Fāsī (1988). Africa from the seventh to the eleventh century. UNESCO. pp. 467–468. ISBN 92-3-101709-8.

- ^ a b Thurstan Shaw (1995). The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. Routledge. p. 433ff. ISBN 0-415-11585-X.

- ^ Robert O. Collins, James McDonald Burns. A history of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press, 2007. p. 62. ISBN 0-521-86746-0.

- ^ H. M. FRIEDE (June 1977). "Iron Age metal working in the Magaliesberg area" (PDF). Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ H. M. FRIEDE (August 1979). "Iron-smelting furnaces and metallurgical traditions of the South African Iron Age" (PDF). Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Golu Timothy (15 October 2007). "Awolowo Inspects Taruga Tourist Site". Leadership. Retrieved 2011-01-09.