This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

Taenia pisiformis, commonly called the rabbit tapeworm, is an endoparasitic tapeworm which causes infection in lagomorphs, rodents, and carnivores. Adult T. pisiformis typically occur within the small intestines of the definitive hosts, the carnivores. Lagomorphs, the intermediate hosts, are infected by fecal contamination of grasses and other food sources by the definitive hosts. The larval stage is often referred to as Cysticercus pisiformis and is found on the livers and peritoneal cavities of the intermediate hosts.[2] T. pisiformis can be found worldwide.

| Taenia pisiformis | |

|---|---|

| |

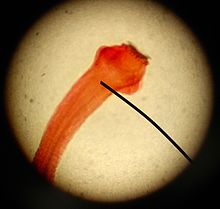

| Taenia pisiformis scolex | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Taeniidae |

| Genus: | Taenia |

| Species: | T. pisiformis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Taenia pisiformis Bloch 1780

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Taenia novella Nuemann, 1896 | |

Description

editT. pisiformis typically infect dogs and other carnivores such as coyotes and foxes. In rabbits, T. pisiformis larvae attach themselves to the liver and intestines, forming cysts 6–18 mm (0.24–0.71 in)[3] in diameter. This is referred to as cysticercosis.[4]

In adult T. pisiformis, the long hooks of the scolex are on average 239.9 μm (0.00944 in) and the short hooks are 140.1 μm (0.00552 in). The dimensions of the suckers are 322.3 μm × 288.1 μm (0.01269 in × 0.01134 in).[5] They can have from 34 to 38 hooks, which can be up to 234 μm (0.0092 in) in length.[6] Adult T. pisiformis can grow between 0.5 to 2 m (20 to 79 in).[6]

The intermediate host is represented by hares and rabbits, in which are found the mesacestoide (the larval stage) known as cysticercus pisiformis. This is found in the peritoneum of the intermediate host and can be ingested by the definite host when the dog or cat feeds on the viscera of such an infected intermediate.[citation needed]

Life cycle

editEggs are introduced into the environment through infected canine feces. In the feces are the gravid proglottids that house the T. pisiformis eggs that will eventually be released from the proglottid onto nearby vegetation. The eggs are then ingested by a rabbit or from any member of the Leporidae family. Once inside the rabbit's gut the larva or oncosphere phase will then penetrate into the intestinal wall until they reach the blood stream. When the worm reaches the liver the larva transforms into a cysticercus form. This cysticercus will stay in the liver for about two to four weeks, then move to the peritoneal cavity where it will wait for the definitive host to eat the rabbit. The definitive hosts are ether dogs or other members of the Canidae family. Once ingested the cysticercus finds its way into the intestine and attaches to the intestinal wall with hooks and suckers. After the worm has time to develop and grow in size, the gravid proglottids is released from the distal end of the parasite and passed in the feces to start a new cycle.[7]

Adult morphology

editThe adult stage consists of a scolex with four suckers and an armed rostellum, a short neck region, a series of immature proglottids with undeveloped reproductive organs, a series of mature proglottids with fully developed male and female reproductive organs, and a series of gravid proglottids with an expanded uterus filled with eggs.[8]

Pathology

editIn rabbits, there are not really defined clinical signs seen for any range of intensity except when there is an externally high intensity. In this case, rabbits look weak or ill. The major illness seen is signs of liver failure. In very few cases the cysts will migrate to the lungs or brain; these cases can cause breathing complication or seizures. In the most extreme cases, the rabbit will have sudden death.[9]

For dogs, there are normally no clinical signs seen for low to moderate infections. In highly infected cases the dog will experience blockage in the intestines.[8] In all cases the proglottids will be seen in the feces.

Diagnostics

editWhen looking for signs of infection in the intermediate host or definitive host, the signs are not very externally seen. For the intermediate host there will be between two and 20 pea-sized cysts found inside the liver.[4] The cysts that are found have one scolex inverted to the middle of the cyst. This shape is called a cysticercus, that is part of the metacestodes stage of life. The ones found in the liver form these bladders that are specifically called Cysticercus pisiformis for T. pisiformis.[9] These signs can only be seen when a necropsy is done to the rabbit. When looking for an infection in dogs there is a more straightforward method. There will be gravid proglottids with striated eggs seen in the feces. This can be found using a fecal float on a sample that can easily be done by a vet.

Treatment and prevention

editTaenis pisiformis infection is very hard to treat in wild rabbits and canines, but it is easier to control pet infections. One way to stop the infection is to prevent dogs from eating wild rabbits or rodents. If the infected rabbit is not eaten then the worm cannot finish its life cycle. Household rabbits usually do not get infected if they are strictly indoor pets, but infection can happen if they are let outside into open grasses.

If the infection is already present then use one of these drugs: Epsiprantel, Praziquantel, Mebendazole, Niclosamide, Bunamindine hydrochloride or Fenbendazole.[7] This will kill the adult stage but not the cyst or egg stage, so several treatments may be needed. Daily doses of Praziquantel for about one to two weeks' time will be effective against larval cysticercosis in rabbits. One dose of Niclosamide or Praziquantel can be very effective in dogs.[citation needed]

Gallery

edit-

Taenia pisiformis cross section

-

Taenia pisiformis egg

-

Cysticercus pisiformis - the larva found in intermediate hosts

-

Taenia pisiformis mature proglottid

References

edit- ^ Hall, M.C. (1920). "The adult taenioid cestodes of dogs and cats, and of related carnivores in North America". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 55 (2258): 1–94. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.55-2258.1.

- ^ Owiny, J.R. (March 2001). "Cysticercosis in laboratory rabbits". Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 40 (2): 45–48. PMID 11300689.

- ^ Darzi, M. M.; Mir, M. S.; Nashiruddullah, N.; Kamil, S. A. (2006-06-17). "Nocardiosis in domestic pigeons (Columba livia)". Veterinary Record. 158 (24): 834–836. doi:10.1136/vr.158.24.834. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 16782860. S2CID 40210192.

- ^ a b "Cysticercosis". Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Esch, G.W.; Self, J.T. (December 1965). "A critical study of the taxonomy of Taenia pisiformis Bloch, 1780; Multiceps multiceps (Leske, 1780); and Hydatigera taeniaeformis Batsch, 1786". Journal of Parasitology. 51 (6): 932–937. doi:10.2307/3275873. JSTOR 3275873. PMID 5848820.

- ^ a b Underhill, B.M. (1920). Parasites and parasitosis of the domestic animals. New York: Macmillan. p. 179.

- ^ a b Han, Jennifer. "Taenia Pisiformis". Taenia Pisiformis. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Taenia pisiformis: Tapeworm". Penn Veterinary Medicine D.V.E.I. Diagnosis of Veterinary Endoparasitic Infections. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ a b Praag, Ph.D., Esther van. "Taenia pisformis". Flat worms: rabbit as an intermediate host. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

Further reading

edit- Roberts, L.S.; Janovy, J. (2008). Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 347. ISBN 9780073028279.