Facial symmetry is one specific measure of bodily symmetry. Along with traits such as averageness and youthfulness, it influences judgments of aesthetic traits of physical attractiveness and beauty.[1] For instance, in mate selection, people have been shown to have a preference for symmetry.[2][3]

Facial bilateral symmetry is typically defined as fluctuating asymmetry of the face comparing random differences in facial features of the two sides of the face.[4] The human face also has systematic, directional asymmetry: on average, the face (mouth, nose and eyes) sits systematically to the left with respect to the axis through the ears, the so-called aurofacial asymmetry.[5]

Directional asymmetry

editDirectional asymmetry is systematic. The average across the population is not "symmetric", but statistically significantly biased on one direction. That means, that individuals of a species can be symmetric, or even asymmetric to the opposite side (see, e.g., handedness), but most individuals are asymmetric to the same side. The relation between directional and fluctuating asymmetry is comparable to the concepts of accuracy and precision in empirical measurements.

There are examples from the brain (Yakovlevian torque) and spine,[6] and inner organs (see axial twist theory), but also from various animals (see Symmetry in biology).

Aurofacial asymmetry

editAurofacial asymmetry (from Latin auris 'ear' and facies 'face') is an example of directed asymmetry of the face. It refers to the left-sided offset of the face (i.e. eyes, nose, and mouth) with respect to the ears. On average, the face's offset is slightly to the left, meaning that the right side of the face appears larger than the left side. The offset is larger in newborns and reduces gradually during growth.[8][9]

Anatomy and definition

editIn contrast to fluctuating asymmetry, directional asymmetry is systematic, i.e. across the population it is systematically more often in one direction than in the other. It means that across the population a deviation is more often to one direction than to the other, i.e., there is a statistically significant bias to one direction. In case of directional asymmetry, most individuals of a species are asymmetric to the same side, even though some individuals can be symmetric, or even asymmetric to the opposite side (cf., e.g., handedness). The relation between directional and fluctuating asymmetry is comparable to the concepts of accuracy and precision in empirical measurements.

The aurofacial asymmetry is defined as the position of the face (mouth, nose and eyes) with respect to the mid plane of the axis through the ears. The asymmetry is expressed as an angle (degrees), i.e. by how many degrees facial landmarks (e.g. tip of the nose) or pairs of landmarks (e.g. inner corners of the eyes (endocanthions are rotated away from the mid plane between the ears.[8]

Magnitude across the face and development

editOn average, the aurofacial asymmetry is slightly larger for the eyes than for the nose, as shown by the figure.

In humans asymmetric growth leads to a gradual reduction of the aurofacial asymmetry.[8] As shown in the graph, the asymmetry decreases from about 2° at birth to about 0.5° in adults.

Theory and evolution

editThe aurofacial asymmetry was discovered[8] after it was predicted by the axial twist theory.[7] According to the theory the facial asymmetry is related to the Yakovlevian torque of the cerebrum, asymmetric heart and bowels and the spine. It is predicted to be common in vertebrates, but this has never been tested.

The axial twist occurs in the early embryo. Shortly after the neurulation, the anterior head region makes a half-turn around the body axis in anti-clockwise direction (looking from tail to head), whereas the rest of the body (except heart and bowels) make a half-turn in clockwise direction. Since the axial twist is located between the ear-region and the forebrain-face-region, it is predicted that the face grows from the left to the midline, as is indeed the case.

Fluctuating asymmetry

editFluctuating asymmetry is the non-systematic variation of individual facial landmarks with respect to the facial midline, i.e., the line perpendicular to the line through the eyes, which crosses the tip of the nose and the chin.

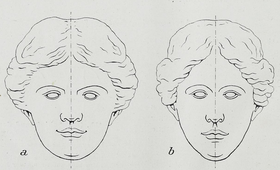

A wide variety of methods have been used to examine the claim that facial symmetry plays a role in judgments of beauty. Blending of multiple faces to create a composite[1][13][14] and face-half mirroring[15] have been among the techniques used.

-

2 right sides

-

Original

-

2 left sides

Conclusions derived from face mirroring, however, have been called into question, because it has been shown that mirroring face-halves creates artificial features. For example, if the nose of an individual is slightly bent to the right side, then mirroring the right side of the face will lead to an over-sized nose, while mirroring the left side will lead to an unnaturally small nose.[16]

Attractiveness

editFacial symmetry has been found to increase ratings of attractiveness in human faces.[1][3] More symmetrical faces are perceived as more attractive in both males and females, although facial symmetry plays a larger role in judgments of attractiveness concerning female faces.[17] Studies have shown that nearly symmetrical faces are considered highly attractive as compared to asymmetrical ones.[9]

Dynamic asymmetries

editHighly conspicuous directional asymmetries can be temporary ones.[18] For example, during speech, most people (76%) tend to express greater amplitude of movement on the right side of their mouth. This is most likely caused by the uneven strengths of contralateral neural connections between the left hemisphere of the brain (linguistic localization) and the right side of the face.[16]

Facial averageness vs. symmetry

editExperiments suggest that symmetry and averageness make independent contributions to attractiveness.[19][20]

Aging

editFacial symmetry is also a valid marker of cognitive aging.[21] Progressive changes occurring throughout life in the soft tissues of the face will cause more prominent facial asymmetry in older faces.[16] Therefore, symmetrical transformation of older faces generally increases their attractiveness while symmetrical transformation in young adults and children will decrease their attractiveness.[16]

Physiognomy

editPhysiognomy or face reading is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. Physiognomy as a practice meets the contemporary definition of pseudoscience and is regarded as such by academics because of its unsupported claims.[22][23][24][self-published source] Nevertheless, the subject is topic of serious scientific research. Statistical correlations does not inform anout possible causal dependence, so if observers judge the personality of (pictures of) symmetric faces differently than asymmetric ones, this might be due to cultural prejudice.

Research indicates that a correlation exists between facial symmetry and the 'big-five' model of personality. The five factors are:[25]

- Openness to experience (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious)

- Conscientiousness (efficient/organized vs. easy-going/careless)

- Extraversion (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved)

- Agreeableness (friendly/compassionate vs. challenging/detached)

- Neuroticism (sensitive/nervous vs. secure/confident)

Accordingly, a positive correlation was found between facial symmetry and extraversion, as judged by others from photographs,[26] as well as by the subjects themselves.[27][28] More symmetrical faces are also judged to be lower on neuroticism but higher on conscientiousness and agreeableness (asymmetrical faces were rated as less agreeable than normal ones, but the more symmetrical were again rated as somewhat less agreeable than the normal).[29] More symmetrical faces are also more likely to have more desirable social attributes assigned to them, such as sociable, intelligent or lively.[26]

The correlation of facial symmetry and neuroticism, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness has remained unclear. Openness and agreeableness appear to be significantly negatively correlated to facial symmetry, while neuroticism and conscientiousness do not seem to be correlated to facial symmetry.[27] With respect to trustworthiness it has been found that the facial muscles become imbalanced when lying.[30]

Evolution and sexual selection

editSexual selection is a theoretical construct within evolution theory. According to sexual selection, mate choice can have profound influence on the preferred features. Sexual selection can only influence features that potential mates can perceive, such as smell, audition (e.g. song) and vision. Such features might be reliable indicators of hidden fitness parameters such as a good immune system or developmental stability.

It has been argued that more symmetric faces are preferred because symmetry might be a reliable sign of such hidden fitness parameters.[31] However it is possible that high facial symmetry in an individual is not due to their superior genetics but due to a lack of exposure to stressors, such as alcohol, during prenatal development.[12]

It has been found that more symmetrical faces are rated as healthier than less symmetrical faces.[3][17] Indeed, facial symmetry was found to be positively associated with the perceived healthiness of the facial skin.[32] Also, facial asymmetry was found to be correlated with physiological, psychological and emotional distress.[33]

Some evidence suggests that face preferences in adults might be correlated to infections in childhood.[34]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Grammer, K.; Thornhill, R. (October 1994). "Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: the role of symmetry and averageness". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 108 (3): 233–42. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.108.3.233. PMID 7924253. S2CID 1205083. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ Rhodes, Gillian; Zebrowitz, Leslie A. (2002). Facial Attractiveness: Evolutionary, Cognitive, and Social Perspectives. Ablex. ISBN 978-1-56750-636-5.

- ^ a b c Jones, B. C.; Little, A. C.; Penton-Voak, I. S.; Tiddeman, B. P.; Burt, D. M.; Perrett, D. I. (November 2001). "Facial symmetry and judgements of apparent health". Evolution and Human Behavior. 22 (6): 417–429. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(01)00083-6.

- ^ Penton-Voak, I. S.; Jones, B. C.; Little; Baker, S.; Tiddeman, B.; Burt, D. M.; Perrett, D. I. (2001). "Symmetry, sexual dimorphism in facial proportions and male facial attractiveness". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 268 (1476): 1617–1623. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1703. PMC 1088785. PMID 11487409.

- ^ de Lussanet, M. H. E. (2019). "Opposite asymmetries of face and trunk and of kissing and hugging, as predicted by the axial twist hypothesis". PeerJ. 7: e7096. doi:10.7717/peerj.7096. PMC 6557252. PMID 31211022.

- ^ Kouwenhoven, Jan-Willem; Vincken, Koen L.; Bartels, Lambertus W.; Castelein, Rene M. (2006). "Analysis of preexistent vertebral rotation in the normal spine". Spine. 31 (13): 1467–1472. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000219938.14686.b3. PMID 16741456. S2CID 2401041.

- ^ a b de Lussanet, Marc H. E.; Osse, Jan W. M. (2012). "An ancestral axial twist explains the contralateral forebrain and the optic chiasm in vertebrates". Animal Biology. 62 (2): 193–216. arXiv:1003.1872. doi:10.1163/157075611X617102. S2CID 7399128.

- ^ a b c d e f de Lussanet, M. H. E. (2019). "Opposite asymmetries of face and trunk and of kissing and hugging, as predicted by the axial twist hypothesis". PeerJ. 7: e7096. doi:10.7717/peerj.7096. PMC 6557252. PMID 31211022.

- ^ a b "Ariadne". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 July 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Blanz, V.; Vetter, T. (1999). "A morphable model for the synthesis of 3D faces". Proceedings of the 26th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques – SIGGRAPH '99. Vol. 7. pp. 187–194. doi:10.1145/311535.311556. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-E751-6. ISBN 0-201-48560-5.

- ^ Troje, N. F.; Bülthoff, H. H. (1996). "Face recognition under varying poses: The role of texture and shape". Vision Research. 36 (12): 1761–1771. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(95)00230-8. PMID 8759445.

- ^ a b Klingenberg, C. P.; Wetherill, L.; Rogers, J.; Moore, E.; Ward, R.; Autti-Rämö, I.; Fagerlund, A. A.; Jacobson, S. W.; Robinson, L. K.; Hoyme, H. E.; Mattson, S. N.; Li, T. K.; Riley, E. P.; Foroud, T. (2010). "Prenatal alcohol exposure alters the patterns of facial asymmetry". Alcohol. 44 (7): 649–657. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.016. PMC 2891212. PMID 20060678.

- ^ Troje, N. F.; Bülthoff, H. H. (1996). "Face recognition under varying poses: The role of texture and shape". Vision Research. 36 (12): 1761–1771. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(95)00230-8. PMID 8759445. S2CID 13115909.

- ^ Blanz, V.; Vetter, T. (1999). "A morphable model for the synthesis of 3D faces". Proceedings of the 26th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '99. pp. 187–194. doi:10.1145/311535.311556. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-E751-6. ISBN 0201485605. S2CID 207637109.

- ^ Kowner, R. (1996). "Facial asymmetry and attractiveness judgment in developmental perspective". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 22 (3): 662–675. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.22.3.662. PMID 8666958.

- ^ a b c d Perrett, D. I.; Burt, D. M.; Penton-Voak, I. S.; Lee, K. J.; Rowland; Edwards, R. (1999). "Symmetry and Human Facial Attractiveness". Evolution and Human Behavior. 20 (5): 295–307. Bibcode:1999EHumB..20..295P. doi:10.1016/s1090-5138(99)00014-8. S2CID 18270137.

- ^ a b Rhodes, G.; Proffitt, F.; Grady, J. M.; Sumich, A. (1998). "Facial symmetry and the perception of beauty". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 5 (4): 659–669. doi:10.3758/bf03208842.

- ^ Kim, Jung-Sik; Shin, Il-Kyu; Soo-Mi, Choi (2010). "Symmetric shape deformation considering facial features and attractiveness improvement". Computer Science and Engineering. 16 (2): 29–37. doi:10.15701/kcgs.2010.16.2.29.

- ^ Rhodes, Gillian; Sumich, Alex; Byatt, Graham (January 1999). "Are Average Facial Configurations Attractive Only Because of Their Symmetry?". Psychological Science. 10 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00106. S2CID 53638699.

- ^ Grammer, Karl; Thornhill, Randy (1994). "Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: The role of symmetry and averageness". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 108 (3): 233–242. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.108.3.233. PMID 7924253. S2CID 1205083.

- ^ Penke, L.; Bates, T. C.; Gow, A. J.; Pattie, A.; Starr, J. M.; Jones, B. C.; Perrett, D. I.; et al. (2009). "Symmetric faces are a sign of successful cognitive aging". Evolution and Human Behavior. 30 (6): 429–437. Bibcode:2009EHumB..30..429P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.727.1978. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.06.001.

- ^ Porter, Roy (2003). "Marginalized practices". The Cambridge History of Science: Eighteenth-century science. Vol. 4 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 495–497. ISBN 978-0-521-57243-9.

Although we bracket physiognomy with Mesmerism as discredited or laughable belief, many eighteenth-century writers referred to it as a useful science with a long history ... Although many modern historians belittle physiognomy as a pseudoscience, at the end of the eighteenth century, it was not merely a popular fad, but also the subject of intense academic debate about the promises it held for progress.

- ^ "physiognomy". The Skeptic's Dictionary. 2013.

- ^ Jaeger, Bastian (June 26, 2020). "Lay beliefs in physiognomy explain overreliance on facial impressions". PsyArXiv.

- ^ Roccas, Sonia; Sagiv, Lilach; Schwartz, Shalom H.; Knafo, Ariel (2002). "The Big Five Personality Factors and Personal Values". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28 (6): 789–801. doi:10.1177/0146167202289008. S2CID 144611052.

- ^ a b Fink, B.; Neave, N.; Manning, J. T.; Grammer, K. (2006). "Facial symmetry and judgements of attractiveness, health and personality". Personality and Individual Differences. 41 (3): 491–499. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.01.017.

- ^ a b Fink, B.; Neave, N.; Manning, J. T.; Grammer, K. (2005). "Facial symmetry and the 'big-five' personality factors". Personality and Individual Differences. 39 (3): 523–529. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.002.

- ^ Pound, N.; Penton-Voak, I. S.; Brown, W. M. (2007). "Facial symmetry is positively associated with self-reported extraversion". Personality and Individual Differences. 43 (6): 1572–1582. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.014.

- ^ Noor, F.; Evans, D. C. (2003). "The effect of facial symmetry on perceptions of personality and attractiveness". Journal of Research in Personality. 37 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1016/s0092-6566(03)00022-9.

- ^ Zaidel, D. W.; Bava, S.; Reis, V. A. (2003). "Relationship between facial asymmetry and judging trustworthiness in faces". Laterality. 8 (3): 225–232. doi:10.1080/13576500244000120. PMID 15513223. S2CID 42358591.

- ^ Scheib, J. E.; Gangestad, S. W.; Thornhill, R. (1999). "Facial attractiveness, symmetry and cues of good genes". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 266 (1431): 1913–1917. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0866. PMC 1690211. PMID 10535106.

- ^ Jones, B. C.; Little, A. C.; Feinberg, D. R.; Penton-Voak, I. S.; Tiddeman, B. P.; Perrett, D. I. (2004). "The relationship between shape symmetry and perceived skin condition in male facial attractiveness". Evolution and Human Behavior. 25 (1): 24–30. Bibcode:2004EHumB..25...24J. doi:10.1016/s1090-5138(03)00080-1.

- ^ Shackelford, T. K.; Larsen, R. J. (1997). "Facial asymmetry as an indicator of psychological, emotional, and physiological distress" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 72 (2): 456–466. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.456. PMID 9107011.

- ^ de Barra, Mícheál; DeBruine, Lisa M.; Jones, Benedict C.; Mahmud, Zahid Hayat; Curtis, Valerie A. (November 2013). "Illness in childhood predicts face preferences in adulthood". Evolution and Human Behavior. 34 (6): 384–389. Bibcode:2013EHumB..34..384D. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.07.001.

External links

edit- FaceResearch – Online studies on facial symmetry by researchers affiliated with University of Aberdeen (Scotland) School of Psychology, and University of St. Andrews (Scotland).

- "A facial symmetry plugin for the GIMP Archived 2019-04-05 at the Wayback Machine"—Try experimenting with facial symmetry, using open source software.

- "Psychological Image Collection at Stirling (PICS) Free Database of pictures of faces

- "FaceBase An interdisciplinary research consortium for facial symmetry

- "Tübinger Face Database An open research database of 200 merged 3-D faces

- "A facial symmetry app for iPhone Experiment with facial symmetry, using a free iPhone app.