The cerebrum (pl.: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain[1] is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfactory bulb. In the human brain, the cerebrum is the uppermost region of the central nervous system. The cerebrum develops prenatally from the forebrain (prosencephalon). In mammals, the dorsal telencephalon, or pallium, develops into the cerebral cortex, and the ventral telencephalon, or subpallium, becomes the basal ganglia. The cerebrum is also divided into approximately symmetric left and right cerebral hemispheres.

| Cerebrum | |

|---|---|

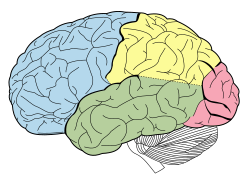

The lobes of the cerebral cortex include the frontal (blue), temporal (green), occipital (red), and parietal (yellow) lobes. The cerebellum (unlabeled) is not part of the telencephalon. | |

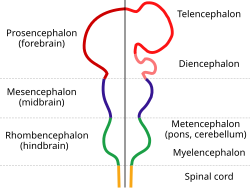

Diagram depicting the main subdivisions of the embryonic vertebrate brain. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɛrɪbrəm/, /sɪˈriːbrəm/ |

| Artery | Anterior cerebral, middle cerebral, posterior cerebral |

| Vein | Cerebral veins |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cerebrum |

| MeSH | D054022 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1042 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.008 A14.1.09.001 |

| TA2 | 5416 |

| TH | H3.11.03.6.00001 |

| TE | E5.14.1.0.2.0.12 |

| FMA | 62000 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

With the assistance of the cerebellum, the cerebrum controls all voluntary actions in the human body.

Structure

editThe cerebrum is the largest part of the brain. Depending upon the position of the animal, it lies either in front or on top of the brainstem. In humans, the cerebrum is the largest and best-developed of the five major divisions of the brain.

The cerebrum is made up of the two cerebral hemispheres and their cerebral cortices (the outer layers of grey matter), and the underlying regions of white matter.[2] Its subcortical structures include the hippocampus, basal ganglia and olfactory bulb. The cerebrum consists of two C-shaped cerebral hemispheres, separated from each other by a deep fissure called the longitudinal fissure.

Cerebral cortex

editThe cerebral cortex, the outer layer of grey matter of the cerebrum, is found only in mammals. In larger mammals, including humans, the surface of the cerebral cortex folds to create gyri (ridges) and sulci (furrows) which increase the surface area.[3]

The cerebral cortex is generally classified into four lobes: the frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal lobes. The lobes are classified based on their overlying neurocranial bones.[4] A smaller lobe is the insular lobe, a part of the cerebral cortex folded deep within the lateral sulcus that separates the temporal lobe from the parietal and frontal lobes, is located within each hemisphere of the mammalian brain.

Cerebral hemispheres

editThe cerebrum is divided by the medial longitudinal fissure into two cerebral hemispheres, the right and the left. The cerebrum is contralaterally organized, i.e., the right hemisphere controls and processes signals (predominantly) from the left side of the body, while the left hemisphere controls and processes signals (predominantly) from the right side of the body.[4] According to current knowledge, this is due to an axial twist that occurs in the early embryo.[5] There is a strong but not complete bilateral symmetry between the hemispheres, while lateralization tends to increase with increasing brain size.[6] The lateralization of brain function looks at the known and possible differences between the two.

Development

editIn the developing vertebrate embryo, the neural tube is subdivided into four unseparated sections which then develop further into distinct regions of the central nervous system; these are the prosencephalon (forebrain), the mesencephalon (midbrain) the rhombencephalon (hindbrain) and the spinal cord.[7] The prosencephalon develops further into the telencephalon and the diencephalon. The dorsal telencephalon gives rise to the pallium (cerebral cortex in mammals and reptiles) and the ventral telencephalon generates the basal ganglia. The diencephalon develops into the thalamus and hypothalamus, including the optic vesicles (future retina).[8] The dorsal telencephalon then forms two lateral telencephalic vesicles, separated by the midline, which develop into the left and right cerebral hemispheres. Birds and fish have a dorsal telencephalon, like all vertebrates, but it is generally unlayered and therefore not considered a cerebral cortex. Only a layered cytoarchitecture can be considered a cortex.

Functions

editNote: As the cerebrum is a gross division with many subdivisions and sub-regions, it is important to state that this section lists only functions that the cerebrum as a whole serves. (See main articles on cerebral cortex and basal ganglia for more information.) The cerebrum is a major part of the brain, controlling emotions, hearing, vision, personality and much more. It controls all precision of voluntary actions, and it functions as the center of sensory perception, memory, thoughts and judgement; the cerebrum also functions as the center of voluntary motor activities.

Motor functions

editUpper motor neurons in the primary motor cortex send their axons to the brainstem and spinal cord to synapse on the lower motor neurons, which innervate the muscles. Damage to motor areas of the cortex can lead to certain types of motor neuron disease. This kind of damage results in loss of muscular power and precision rather than total paralysis.

Sensory processing

editThe primary sensory areas of the cerebral cortex receive and process visual, auditory, somatosensory, gustatory, and olfactory information. Together with association cortical areas, these brain regions synthesize sensory information into our perceptions of the world.

Olfaction

editThe olfactory bulb, responsible for the sense of smell, takes up a large area of the cerebrum in most vertebrates. However, in humans, this part of the brain is much smaller and lies underneath the frontal lobe. The olfactory sensory system is unique since the neurons in the olfactory bulb send their axons directly to the olfactory cortex, rather than to the thalamus first. Olfaction is also the only sense that is represented by the ipsilateral side of the brain. Damage to the olfactory bulb results in a loss of olfaction (the sense of smell).

Language and communication

editSpeech and language are mainly attributed to parts of the cerebral cortex. Motor portions of language are attributed to Broca's area within the frontal lobe. Speech comprehension is attributed to Wernicke's area, at the temporal-parietal lobe junction. These two regions are interconnected by a large white matter tract, the arcuate fasciculus. Damage to the Broca's area results in expressive aphasia (non-fluent aphasia) while damage to Wernicke's area results in receptive aphasia (also called fluent aphasia).

Learning and memory

editExplicit or declarative (factual) memory formation is attributed to the hippocampus and associated regions of the medial temporal lobe. This association was originally described after a patient known as HM had both his left and right hippocampus surgically removed to treat chronic [temporal lobe epilepsy]. After surgery, HM had anterograde amnesia, or the inability to form new memories.

Implicit or procedural memory, such as complex motor behaviors, involves the basal ganglia.

Short-term or working memory involves association areas of the cortex, especially the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, as well as the hippocampus.

Other animals

editIn the most primitive vertebrates, the hagfishes and lampreys, the cerebrum is a relatively simple structure receiving nerve impulses from the olfactory bulb. In cartilaginous and lobe-finned fishes and also in amphibians, a more complex structure is present, with the cerebrum being divided into three distinct regions. The lowermost (or ventral) region forms the basal nuclei, and contains fibres connecting the rest of the cerebrum to the thalamus. Above this, and forming the lateral part of the cerebrum, is the paleopallium, while the uppermost (or dorsal) part is referred to as the archipallium. The cerebrum remains largely devoted to olfactory sensation in these animals, in contrast to its much wider range of functions in amniotes.[9]

In ray-finned fishes, the structure is somewhat different. The inner surfaces of the lateral and ventral regions of the cerebrum bulge up into the ventricles; these include both the basal nuclei and the various parts of the pallium and may be complex in structure, especially in teleosts. The dorsal surface of the cerebrum is membranous, and does not contain any nervous tissue.[9]

In the amniotes, the cerebrum becomes increasingly large and complex. In reptiles, the paleopallium is much larger than in amphibians and its growth has pushed the basal nuclei into the central regions of the cerebrum. As in the lower vertebrates, the grey matter is generally located beneath the white matter, but in some reptiles, it spreads out to the surface to form a primitive cortex, especially in the anterior part of the brain.[9]

In mammals, this development proceeds further, so that the cortex covers almost the whole of the cerebral hemispheres, especially in more developed species, such as the primates. The paleopallium is pushed to the ventral surface of the brain, where it becomes the olfactory lobes, while the archipallium becomes rolled over at the medial dorsal edge to form the hippocampus. In placental mammals, a corpus callosum also develops, further connecting the two hemispheres. The complex convolutions of the cerebral surface (see gyrus, gyrification) are also found only in higher mammals.[9] Although some large mammals (such as elephants) have particularly large cerebra, dolphins are the only species (other than humans) to have cerebra accounting for as much as 2 percent of their body weight.[10]

The cerebra of birds are similarly enlarged to those of mammals, by comparison with reptiles. The increased size of bird brains was classically attributed to enlarged basal ganglia, with the other areas remaining primitive, but this view has been largely abandoned.[11] Birds appear to have undergone an alternate process of encephalization,[12] as they diverged from the other archosaurs, with few clear parallels to that experienced by mammals and their therapsid ancestors.

Additional images

edit-

Cerebrum. Lateral face. Deep dissection.

-

Cerebrum. Medial face. Deep dissection.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "BrainInfo". braininfo.rprc.washington.edu.

- ^ Arnould-Taylor, William (1998). A Textbook of Anatomy and Physiology. Nelson Thornes. p. 52. ISBN 9780748736348. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Angevine, J.; Cotman, C. (1981). Principles of Neuroanatomy. NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195028850. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ a b Rosdahl, Caroline; Kowalski, Mary (2008). Textbook of Basic Nursing (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 189. ISBN 9780781765213. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ de Lussanet, M.H.E.; Osse, J.W.M. (2012). "An ancestral axial twist explains the contralateral forebain and the optic chiasm in vertebrates". Animal Biology. 62 (2): 193–216. arXiv:1003.1872. doi:10.1163/157075611X617102. S2CID 7399128.

- ^ Ebbesson, Sven O. E.; Ito, Hironobu (1980). "Bilateral retinal projections in the black piranah (Serrasalmus niger)". Cell Tissue Res. 213 (3): 483–495. doi:10.1007/BF00237893. PMID 7448850. S2CID 2406618.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2014). Developmental biology (10th ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. ISBN 978-0-87893-978-7.

- ^ Kandel, Eric R., ed. (2006). Principles of neural science (5th ed.). Appleton and Lange: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ a b c d Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 536–543. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ T.L. Brink (2008). "Unit 4: The Nervous System.". Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach (PDF). p. 62.

- ^ Jarvis ED, Güntürkün O, Bruce L, et al. (2005). "Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate brain evolution". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 (2): 151–9. doi:10.1038/nrn1606. PMC 2507884. PMID 15685220.

- ^ Emery NJ (2006-01-29). "Cognitive ornithology: the evolution of avian intelligence". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361 (1465): 23–43. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1736. PMC 1626540. PMID 16553307.