Surinamese Maroons (also Marrons, Businenge or Bushinengue, meaning black people of the forest) are the descendants of enslaved Africans that escaped from the plantations and settled in the inland of Suriname. The Surinamese Maroon culture is one of the best-preserved pieces of cultural heritage outside of Africa. Colonial warfare, land grabs, natural disasters and migration have marked Maroon history. In Suriname six Maroon groups — or tribes — can be distinguished from each other.

Maroon family in Suriname, c. 1900. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 117,567 (2012) 21.7% of Suriname's population[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Saramaccan, Aukan, Kwinti, Matawai, Sranan Tongo, Dutch | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Winti | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Afro-Surinamese |

Demographics

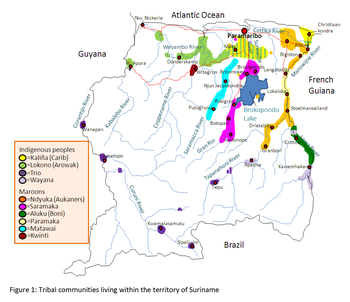

editThere are six major groups of Surinamese Maroons,[2] who settled along different river banks:

- Aluku (or Boni) at the Commewijne River later Marowijne River,

- Kwinti at the Coppename River,

- Matawai at the Saramacca River,

- Ndyuka (or Aukan) at the Marowijne and Commewijne Rivers

- Paamaka (Paramaccan) at the Marowijne River

- Saamaka (Saramaccan) at the Suriname River

Distribution

editLanguage

editThe sources of the Surinamese Maroon vocabulary are the English language, Portuguese, some Dutch and a variety of African languages. Between 5% and 20% of the vocabulary is of African origin. Its phonology is closest to that of African languages. The Surinamese Maroons have developed a system of meaning-distinctive intonation, as is common in Africa.

Religion

editThe traditional Surinamese Maroon religion is called Winti. It is a syncretization of different African religious beliefs and practices brought in mainly by the Akan and Fon enslaved peoples. Winti is typical for Suriname, where it originated. The religion has a pantheon of spirits called Winti. Ancestor veneration is central. It has no written sources, nor a central authority. Practising Winti was forbidden by law for nearly one hundred years. Since the 1970s, many Maroons have moved to urban areas and have become evangelical. After the turn of the millennium Winti gained momentum. It is becoming more popular, especially in the Maroon diaspora.[citation needed]

| Religion of Surinamese Maroons (2012)[3] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Religion | Number of adherents | % |

| Christianity | 74,392 | 63.3% |

| Catholic | 27,626 | 23.5% |

| Pentecostal | 21,746 | 18.5% |

| Moravian Church | 19,093 | 16.2% |

| Other christian | 5,927 | 5.1% |

| No religion | 25,270 | 21.5% |

| Winti | 9,657 | 8.2% |

| No answer | 5,116 | 4.4% |

| Other | 1,755 | 1.5% |

| Don't know | 1,377 | 1.2% |

| Total | 117,567 | 100.0% |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Censusstatistieken 2012" (PDF). Algemeen Bureau voor de Statistiek in Suriname (General Statistics Bureau of Suriname). p. 76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ Cf. Langues de Guyane, sous la direction de Odile RENAULT-LESCURE et Laurence GOURY, Montpellier, IRD, 2009.

- ^ Tabel 7.3. Totale bevolking naar geloofsovertuiging/godsdienst en etnische groep [1]. Gearchiveerd op 5 februari 2023.

Further reading

edit- Betian, Desmo; Betain, Wemo; Cockle, Anya (2000). Parlons saramaka. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7384-9835-9.

- Bindault, Michel (1993). Lexique français-bushi-nenge et bushi-nenge-français. Grand-Santi: Michel Bindault. OCLC 463856989. BnF 35706051m.[self-published source]

- Campbell, Corinna (2020). The cultural work: Maroon performance in Paramaribo, Suriname. Music/culture (First ed.). Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-7956-0.

- Campbell, Corinna (2012). Personalizing Tradition: Surinamese Maroon Music and Dance in Contemporary Urban Practice (PhD). Harvard University.

- Dakan, Philippe (2003). Napi tutu : l'enfant, la flûte et le diable : conte aluku : contes de tradition orale en Guyane. CRDP de Guyane. ISBN 978-2-908931-47-1.

- Godon, Élisabeth (2008). Les enfants du fleuve. Les écoles du fleuve en Guyane française: le parcours d'une psy (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-19243-0.

- Goury, Laurence (2003). Le ndyuka : une langue créole du Surinam et de Guyane française. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7475-4314-9.

- Goury, Laurence; Migge, Bettina (2003). Grammaire du nengee : introduction aux langues aluku, ndyuka et pamaka. Paris: IRD. ISBN 978-2-7099-1529-8.

- Les leçons d'Ananshi l'araignée, conte bushinengué (in French). SCEREN-CRDP de Guyane. 2007. ISBN 978-2-908931-83-9.

- Price, Richard (1991). First-time: the historical vision of an Afro-American people. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-2984-0.

- Price, Richard (1994). Les premiers temps : la conception de l'histoire des Marrons saramaka (in French). Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-014754-5.

- Van Lier, Willem F. (1939). Notes sur la vie spirituelle et sociale des Djuka (Noirs réfugiés Auca) au Surinam (in French). Translated by Kousbroek, H. R. Universiteit Leiden. hdl:1887.1/item:970471.

- Vernon, Diane (1992). Les représentations du corps chez les Noirs Marrons Ndjuka du Surinam et de la Guyane française (PDF). ORSTOM. ISBN 2-7099-1106-X.