Starvation of a civilian population is a war crime, a crime against humanity, and an act of genocide according to modern international criminal law.[1][2][3] Starvation has not always been illegal according to international law; the starvation of civilians during the siege of Leningrad was ruled to be not criminal by a United States military court, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, though imposing limits, "accepted the legality of starvation as a weapon of war in principle".[4] Historically, the development of laws against starvation has been hampered by the Western powers who wish to use blockades against their enemies; however, it was banned in 1977 by Protocol I and Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions and criminalized by the Rome Statute. Prosecutions for starvation have been rare.

Purpose and causes

editBridget Conley and Alex de Waal enumerate several reasons why a perpetrator might choose to employ starvation: "(i) extermination or genocide; (ii) control through weakening a population; (iii) gaining territorial control; (iv) flushing out a population; (v) punishment; (vi) material extraction or theft; (vii) extreme exploitation; (viii) war provisioning; and (ix) comprehensive societal transformation".[3] There are no systematic studies of the perpetration of starvation crimes.[5]

Victims

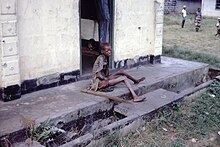

editDuring starvation events, most deaths occur to young children and the elderly, as well as pregnant and lactating mothers. Survivors can face lifelong health impairments.[3]

War crime

editStarvation has been extensively used as a method of warfare throughout history and into the twenty-first century. For most of this time, it was not considered a criminal act.[7][8] From the mid-nineteenth century to World War I, legal attempts to limit blockades were largely successful at preventing starvation in European wars, but not famine in colonial empires.[9] Historians Nicholas Mulder and Boyd van Dijk argue that it took a long time for starvation to be recognized as criminal because it is important to blockade tactics implemented in war, widely employed by the Western powers such as the United Kingdom and France that played a major role in the development of international law.[10]

Starvation was employed by the Allies during and after World War I,[11] by all powers during World War II,[12] and was not prohibited by the 1948 Genocide Convention or the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.[13] While the Soviet Union and Switzerland tried to limit the use of blockade in the 1949 Geneva Convention, the NATO block watered these provisions down because it wanted to preserve blockade as a weapon against communism. The final draft "accepted the legality of starvation as a weapon of war in principle".[4]

The blockade of Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War was the most well-known example during the next decades of starvation employed during a war.[14] The International Committee of the Red Cross recognized that the failure of its relief effort was due in part to the blockade law endorsed by the Western powers, and increased its efforts to secure stronger legal protections for civilians.[15] According to the 1977 Protocol II, "objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population" are protected and attacks against them are prohibited.[3]

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court includes starvation as a war crime when committed within an international armed conflict. In 2018, Switzerland proposed extending this provision to non-international armed conflict (NIAC).[6] This proposal was accepted by all of the states parties to the Rome Statute and ratified by eleven states.[16] Nevertheless, many experts argue that starvation in NIAC is already criminalized in international customary law, and prosecutions have already taken place.[6]

Legal scholar Tom Dannenbaum argues that blockade-induced starvation should be considered a form of torture and prohibited on this basis.[17]

Crimes against humanity

editAccording to the Rome Statute, crimes against humanity does not have an explicit provision for starvation, however, starvation would satisfy the requirements of some of the enumerated crimes against humanity. One of these provisions is "other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health".[1][18] This provision does not require deliberate intent to cause starvation, only "knowledge of the likelihood of the relevant injury".[1] Starvation could also be prosecuted as torture, although depending on the legal forum, prosecutors might need to prove a specific purpose of the starvation or that the victims were under the control of the perpetrator.[1] If the starvation results in death, murder is also a crime against humanity. In the Karadžić case, the ICTY convicted Radovan Karadžić of the crime against humanity of murder for the starvation of prisoners. For murder to be charged, the accused's act or omission must have been made with intent to kill, inflict grievous bodily harm, or knowledge that death would occur.[1] The crime against humanity of extermination includes "the intentional infliction of conditions of life, inter alia the deprivation of access to food and medicine, calculated to bring about the destruction of part of a population".[18] Unlike murder, it excludes dolus eventualis, and according to Ventura, "the accused must act with the intent to kill on a massive scale or to systematically subject a large number of people to conditions that would lead to their death."[1]

Genocide

editIf committed with the intent to fully or partly destroy a protected group, starvation could be prosecuted as an act of genocide.[1]

International human rights law

editStarvation also violates the right to food.[3]

Case law

editUnlike direct killing, there is a degree of distance between the perpetrator's actions in a starvation crime and the resulting effect on the victims. This aspect makes it more difficult to prosecute.[3][19] Historically, prosecutions for starvation have been rare.[7]

The judges at the High Command trial—a United States military court convened to judge German war crimes—the judge ruled that "the cutting off every source of sustenance from without is deemed legitimate. ... We might wish the law were otherwise, but we must administer it as we find it".[7][20] Even such actions as killing civilians fleeing a siege was ruled to be legal during the trial.[14] Blockade causing starvation—including the siege of Leningrad where it killed hundreds of thousands of Soviet civilians—was deemed legal by Allied judges.[5]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Ventura, Manuel JB (2019). "Prosecuting Starvation under International Criminal Law". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 17 (4): 781–814. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqz043.

- ^ Luciano, Simone Antonio (2023). "Starvation at the International Criminal Court: Reflections on the Available Options for the Prosecution of the Crime of Starvation". International Criminal Law Review. 23 (2): 284–320. doi:10.1163/15718123-bja10149. ISSN 1571-8123.

- ^ a b c d e f Conley, Bridget; de Waal, Alex (2019). "The Purposes of Starvation". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 17 (4): 699–722. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqz054.

- ^ a b Mulder & van Dijk 2021, pp. 383–384.

- ^ a b Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 371.

- ^ a b c D’Alessandra, Federica; Gillett, Matthew (2019). "The War Crime of Starvation in Non-International Armed Conflict". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 17 (4): 815–847. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqz042.

- ^ a b c Jordash, Wayne; Murdoch, Catriona; Holmes, Joe (1 September 2019). "Strategies for Prosecuting Mass Starvation". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 17 (4): 849–879. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqz044.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 370.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 372.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 374.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 377.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 378.

- ^ a b Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 384.

- ^ Mulder & van Dijk 2021, p. 385.

- ^ Kersten, Mark (16 January 2023). "Fair Labelling the Crime of Starvation: Why Ratifying the War Crime of Starvation Matters". Justice in Conflict. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Dannenbaum, Tom (2021–2022). "Siege Starvation: A War Crime of Societal Torture". Chicago Journal of International Law. 22: 368.

- ^ a b Rome Statute article 7

- ^ Dannenbaum, Tom (2022). "Criminalizing Starvation in an Age of Mass Deprivation in War: Intent, Method, Form, and Consequence". Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law. 55: 681.

- ^ Marcus, David (2003). "Famine Crimes in International Law". The American Journal of International Law. 97 (2): 245–281. doi:10.2307/3100102. ISSN 0002-9300.

Further reading

edit- Conley, Bridget; de Waal, Alex; Jordash, Wayne; Murdoch, Catriona (2022). Accountability for Mass Starvation: Testing the Limits of the Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286473-4.

- Mulder, Nicholas; van Dijk, Boyd (2021). "Why Did Starvation Not Become the Paradigmatic War Crime in International Law?". Contingency in International Law: On the Possibility of Different Legal Histories. Oxford University Press. pp. 370–. ISBN 9780192898036.