Saint Brandon (French: Saint-Brandon), also known as the Cargados Carajos Shoals, is a southwest Indian Ocean archipelago of sand banks, shoals and islets belonging to the Republic of Mauritius. It lies about 430 km (270 mi) northeast of the island of Mauritius. It consists of five island groups, with about 28-40 islands and islets in total, depending on seasonal storms and related sand movements.[1]

Native name: Cargados Carajos | |

|---|---|

| Geography | |

| Location | Indian Ocean |

| Coordinates | 16°35′S 59°37′E / 16.583°S 59.617°E |

| Archipelago | Cargados Carajos |

| Total islands | 22 |

| Major islands | Albatross Island, Raphaël, Avocaré Island, L'Île Coco and L'île du Sud |

| Area | 1.3 km2 (0.50 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

Mauritius | |

| Largest settlement | Île Raphaël (pop. 30) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 40 (2022) |

| Pop. density | 48/km2 (124/sq mi) |

The archipelago is low-lying and is prone to substantial submersion in severe weather, but also by annual tropical cyclones in the Mascarene Islands. It has an aggregate land area estimated variously at 1.3 km2 (0.50 sq mi) and 200 ha (500 acres).[1] The islands have a small resident population of around 60 fishermen working for the Raphael Fishing Company.[2] The bulk of this population, approximately 40 people, reside on Île Raphael, with smaller settlements existing on Avocaré Island, L'Île Coco, and L'île du Sud.

In the early 19th century, most of the islands were used as fishing stations. Today, only one resident fishing company operates on the archipelago with three fishing stations and accommodation for fly fishermen on L'île du Sud, Île Raphael and L'Île Coco. The isolated Albatross Island reverted to the State of Mauritius in May 1992 and has since been abandoned.[3] Thirteen of the thirty islands were subject to a legal challenge from 1995 until 2008 between a certain Mr. Talbot (acting with the government) and the Raphael Fishing Company, this being resolved by Mauritius's highest Court of Appeal in 2008[4] which converted the erstwhile permanent lease into a permanent grant for the resident fishing company.[5]

As is common amongst small, remote islands, the fauna and flora display a high degree of endemism which attracts visitors and international conservationists because of the critical role these remote islands play in the conservation of endangered species. The endangered green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) nests here as does the critically endangered Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) which may be unique to the extent that they are eventually confirmed as being genetically different from those further north in the Chagos islands and the Seychelles.

The islands, designated a Key Biodiversity Area under CEPF, are also instrumental in the preservation of many bird species that are either vulnerable or near-threatened and were recommended as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) by the World Bank (1998). The World Bank's management plan was accepted, with a few changes, at Mauritian ministry level in its "Blue Print for the Management of St. Brandon" in 2002 and thereafter approved by the government of Mauritius in 2004.[6]

Etymology

editIn the early 1500s, the Portuguese labelled the islands Cargados Carajos on charts such as the Cantino Planisphere of 1502, which identified them as baixos ("low-lying"), with a surround of crosses to identify the danger to shipping.[citation needed]

Various explanations have been given for the islands having subsequently been named Saint Brandon. One of these is that it is an anglicized name of the French town of Saint-Brandan, possibly given by French sailors and corsairs that sailed to and from Brittany.[7]

Another explanation is that the name derived from the mythical Saint Brendan's Island that goes back to Saint Brendan of Clonfert, Brendan the Navigator, because French sailors associated the atoll with the patron saint of sailors.[citation needed]

The name Cargados Carajos, which refers to the "loaded crow's nest" of a Portuguese caravel that was required to successfully sail through the dangerous atoll, remains in use as well.[citation needed]

Climate

edit| Climate data for Saint Brandon (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.6 (96.1) |

35.1 (95.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

33.8 (92.8) |

34.3 (93.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.4 (88.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 28.4 (83.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.6 (63.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 141.5 (5.57) |

184.7 (7.27) |

140.0 (5.51) |

125.5 (4.94) |

71.2 (2.80) |

46.1 (1.81) |

47.5 (1.87) |

46.6 (1.83) |

29.3 (1.15) |

27.2 (1.07) |

36.9 (1.45) |

77.6 (3.06) |

974.1 (38.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.3 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 11.4 | 9.2 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 114.6 |

| Source: NOAA[8] | |||||||||||||

Geography

editGeographically, the archipelago is part of the Mascarene Islands and is situated on the Mascarene Plateau formed by the separation of the Mauritia microcontinent during the separation of India and Madagascar around 60 million years ago from what is today the African continent.

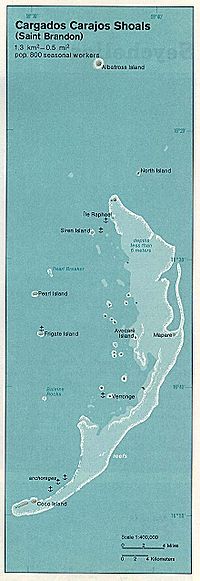

The reef measures more than 50 km (31 mi) from north to south and is 5 km (3.1 mi) wide, cut by three passes. The reef area is 190 km2 (73 sq mi). The total number of islands on the reef varies but usually number around 40. Siren Island, L'île du Sud, Pearl Island, and Frigate Island are west of the reef, while North Island is about 4 km (2.5 mi) northeast of the northern tip of the reef. Albatross Island, about 18 km (11 mi) north, is geographically a separate single coral island.

Albatross Island is the highest point at 6 m (20 ft) above sea level and the largest of the islands in the group, with an area of 1.01 km2 (0.39 sq mi), followed by Raphaël, Tortue, Avocaré Island, L'Île Coco and L'île du Sud.

Temperatures range from 23–26 °C (73–79 °F), with rainfall of 1,050 mm (41 in) a year, most falling in January to April. The climate is dominated by the south-east trades. Cyclones can cause considerable damage. In 1948, Il aux Fous disappeared and Avoquer was submerged by two meters of water. Petit ile Longue was swept away in a later cyclone, but is now reappearing. The South Equatorial Current is dominant.[9]

List of named islands

editEcology

editReefs

editSt. Brandon comprises about 190 km2 (73 sq mi) of reefs. It has one of the longest algal ridges in the Indian Ocean. Coconut trees can be found on a few islands as well as a variety of bushes and grass. The islands are covered with white granular sand from eroded coral, and a thick layer of guano can be found on some islands.

The western part of the bay has a coral bank and a fringing reef, dominated by staghorn Acropora, with an irregular front which merges with the coral banks; the reef flat has appreciable coral cover. North of this, or deeper into the bay, are several isolated patches of coral growing in deeper water.

The eastern border has reefs with a greater diversity of corals, in particular, enormous hillocks of Pavona spp. with Mycedium tenuicostatum which is unusual in Mauritius. On the sandy substrate, Goniopora and Pontes provide hard substrate for several other species, notably Acropora and Pavona. Large tabular 'Acropora corals are also conspicuous, and when dead or overturned, provide substrate for other colonizers. These patches have expanded and fused to provide the numerous, large coral banks found in the Bay. Only twenty-eight coral species have been recorded which is probably due to the uniform habitat. Further offshore lies a peripheral fringing reef.

This complex of low islands, coral reefs and sand banks arises from a vast shallow submarine platform. The main structure is a large, 100 km (62 mi) long crescent-shaped reef whose convex side faces towards the south-east trades and the South Equatorial Current. The reef front of the main reef recurves inwards at both ends and is cut by two or three passes.

The main reef has a very broad reef flat, extending up to several hundred metres across in parts. Together with much of the broad reef flat it is emergent at low tides. Apart from calcareous red algae it supports a few pocilloporoid corals. Down to at least 20 m (66 ft) depth the substrate is swept clear of attached biota, although on the sides of spurs or buttresses a few corals exist. Underwater photographs of some of the numerous knolls and banks behind the reef show that the density of corals and soft corals is typical of many very sedimented areas and shallow lagoons in the Indian Ocean.

The islands are home to at least 26 species of seabirds such as Red-footed booby, sooty terns, and white terns. Endangered Green turtles and Critically Endangered hawksbill turtles nest on the islands.

Given the total isolation of the atoll and the low level of investment and scientific research carried out to date, there is the possibility of the discovery of new species. In May 2013, Novaculops alvheimia, a new species of labrid fish, was discovered on the St Brandon atoll.[10][11]

Molluscs

editAmong molluscs found in Saint Brandon, Ophioglossolambis violacea is famous for its violet hue. It is a very rare species of large sea snail (a marine gastropod mollusc in the Strombidae family) endemic to Saint Brandon. It is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, which is an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological species. Below is a selection of other molluscs from Saint Brandon.

-

Tridacna_lorenzi_(MNHN-IM-2000-30800)_003

-

Conus_lecourtorum_(MNHN-IM-2000-24257)

-

Bistolida_piae_(MNHN-IM-2000-9546)

-

Ficus_dandrimonti_(MNHN-IM-2000-25145)

-

Chicoreus_janae_(MNHN-IM-2000-26871)

-

Turbo_lorenzi_(MNHN-IM-2000-27219)

-

Tridacna_lorenzi_(MNHN-IM-2000-30800)_001

-

Bistolida_nanostraca_(MNHN-IM-2000-24515)

International launch of the Saint Brandon Conservation Trust

editAt the Corporate Council on Africa US Africa Business Summit in Dallas on 8 May 2024,[12] The Saint Brandon Conservation Trust presented Saving Africa's Rarest Species[13] and the panel session explored Mauritius as a model for African ecosystem conservation and the importance of critical relationships with global NGOs to help unite common environmental interests across the generational, cultural and geographical boundaries. The panel discussed the success story of the Mauritian Kestrel, highlighting the Kestrel's current status as the national bird. The session also included a case study on the rescue and rehabilitation of three rare reptile species following the Wakashio oil spill in July 2020. The session concluded with an insight into an independent NGO: the Saint Brandon Conservation Trust. The session lasted for one hour and included three videos, graphics and photography used by the presenters and concluded with an interactive Q+A session with delegates from the audience which were moderated. The event was conceived and sponsored by the vice-chairman of Corporate Council on Africa as a prime mover in the creation of America's governing law on trade with Africa (AGOA), supporting and lobbying for Africa and for his homeland, Mauritius. The Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) was enacted in 2000 and, after completing its initial 15-year period of validity, the AGOA legislation was extended, on June 29, 2015, by a further 10 years, to 2025.

Case Study 1, The Mauritian Kestrel: A Successful African Conservation Story: The Mauritius kestrel (Falco punctatus), originally from the adjoining deep valleys of the Bambous Mountain Range, was saved from almost certain extinction by Professor Carl Jones, Chief Scientist of the Durrell Conservation Trust, through hand-rearing the last breeding pair in existence and releasing their chicks into the safety of Kestrel Valley sanctuary. Starting in 1994, 331 birds were released into the wild in Mauritius. Monitoring and protection of the Mauritius Kestrel are ongoing at Kestrel Valley with and active contribution to the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation.

History

editBecause all Portuguese maps of discovery were destroyed by the 1 November 1755 Lisbon Earthquake,[14] there is no way of knowing for certain, but hearsay suggests that Saint Brandon was discovered around 975 A.D. by Arabian sailors along with Dina Arobi ("Abandoned Island"), now known as the island of Mauritius. It can also be found listed as Baixos on the 1502 Cantino Planisphere map, which was an illegal copy of a Portuguese map that documented the Arab discoveries and was smuggled to Italy and, for this reason, survived.

It was named Cargados Carajos in 1506 by Portuguese sailors who went ashore for provisioning after having been blown off course from their attempted passage through the Mozambique Channel (the shortest and safest route) on their way to India. Pirates and French corsairs have also used the islands as a refuge.

In 1598, the Dutch occupied the islands.

On 12 February 1662, the East India Ship Arnhem ran aground on the Saint Brandon Rocks.[15] Volkert Evertsz, the captain, and other survivors of the wreck survived by piloting a small boat to Mauritius, and are thought to have been the last humans to see living dodos.[16][17] They survived the three months until their rescue by hunting "goats, birds, tortoises and pigs".[18] Evertsz was rescued by the English ship Truroe in May 1662.[18][19] Seven of the survivors chose not to return with the first rescue ship.[20]

Mauritius and its associated islands were colonised by the French some time around 1715, granted by the King of France to the Compagnie des Indes in 1726 but retroceded to the French Crown in 1765. Saint Brandon was referred to as Cargados in Samuel Dunn's world map of 1794.

On 9 June 1806, the French general Charles Decaen ordered the corsair Charles Nicolas Mariette to send a spying mission to Saint Brandon and to leave six men on the most prominent island and, on his return trip to Mauritius, to ascertain once and for all that Cargados Carajos and Saint Brandon were the same shoal. The frigate Piemontaise under the command of Louis Jacques Eperon le Jeune departed on 11 June 1806.[21]

In 1810, the islands were taken by force by Britain, becoming a British crown colony.

From October to November 1917, the Saint Brandon Islands and, in particular, the lagoon of L'Île Coco, were used as a base by the German raiding vessel Wolf, commanded by Karl August Nerger.[22] On the island, Wolf transferred stoking coal and stores from the captured Japanese ship Hitachi Maru which took three weeks. The coal was necessary for the raider's return to Germany. To do so, Wolf had to run a gauntlet of Allied warships from near the Cape of the Good Hope to the North Atlantic. On 7 November 1917, the Germans scuttled Hitachi Maru 26 km (16 mi) off shore and Wolf departed.[23]

The most common employment on St. Brandon in 1922 was agriculture, with a manager, assistant manager and eleven labourers. Only two young men were recorded as working as fishermen. Three men worked as carpenters, one as a mason, one as a shoemaker and another as a domestic servant. There was no indication that the guano mines were operating.[24] The islands were later mined for phosphates derived from guano until mining activities ceased in the mid-20th century.

Amateur radio operators have occasionally conducted DXpeditions on Saint Brandon. In February and March 2023, the 3B7M expedition made more than 120,000 radio contacts.[25]

Shipwrecks

editShipwrecks on the low-lying, rocky reefs of Saint Brandon have been recorded since as early as 1591.

- In 1591, the Portuguese ship 'Bom Jesus' sank in Saint Brandon. Its exact whereabouts are not known.[26]

- On 12 February 1662, the Dutch East Indiaman sailing ship Arnhem wrecked itself on the rocks at Saint Brandon.[27][28][29]

- 1780s - The English ship, the Hawk, foundered on Saint Brandon on her return to Europe from Surat.[30]

- On 25 October 1795, a vessel called l'Euphrasie arrived in Port Louis with five survivors from a shipwreck in St. Brandon related to a corsair ship called La Revanche. A certain crewman called Landier is described as leading this group of survivors. The other eight crew members perished.[31]

- On 7 July 1818, the sailing vessel Cabalva, built by Wells, Wigram & Green in 1811 and owned by the East India Company, struck the reef at St. Brandon on its way to China and was destroyed. Captain James Dalrymple and several other lost their lives.[32][33]

- On 15 September 1845, the sailing ship Letitia ran aground on the Frigate islet. Captain Malcolm drowned.[34]

- On 16 November 1850, the barque 'Mary' also foundered on Frigate island in Saint Brandon, probably for a similar reason, namely a navigational confusion (using Horsburg's Charts) of St. 'Brandon Rocks' with the reefs of Cargados Carajos when they should be considered as one and the same group of isles, islands and reefs.[33][clarification needed]

- In 1850, the sailboat 'Indian' also sank on the Saint Brandon shoals. Not much is on record about this shipwreck.[33]

- On 3 October 1969, the Russian tugboat Argus wrecked itself on the reef at Saint Brandon. A total of 38 men were rescued.[35][36]

- In 2012, a tuna longliner ran aground on the reef crest of Saint Brandon's atoll. It broke into three pieces which was moved by currents and storms into the lagoon.[37]

- On 29 November 2014, during the second leg of the 2014–15 Volvo Ocean Race, the sailing boat Team Vestas Wind ran aground on Saint Brandon.[38]

- On 1 February 2015, the fishing vessel Kha Yang, with 250,000 liters of fuel in its tanks, ran aground on the reef of Saint Brandon.[39] Its crew of 20 were rescued shortly after its grounding, and a salvage operation pumped the fuel from its tanks a few weeks later.[40][41]

- On 2 February 2017, the long bulk carrier Alam Manis ran aground on its way to Pipavav from Richards Bay.[42]

- On 5 June 2021, the FV Sea Master belonging to the Mauritian company Hassen Taher was shipwrecked on Albatross Island.[43]

- On 5 December 2022, the Taiwanese fishing vessel FV Yu Feng 67 ran aground off L'île du Sud.[44] The twenty crew were saved by Raphaël Fishing Company vessels at the direct request of the Government at crisis meetings held in Port Louis. Seventy tonnes of diesel and around twenty tonnes of rotting bait fish gradually flowed into the lagoon and poisoned flora and fauna.[45]

Demographics

editThe main settlement and the administrative centre of Saint Brandon is Île Raphaël and can have up to 35 resident employees, a coast guard outpost and meteorological station (with eight residents in 1996). Smaller settlements exist on Avocaré Island, L'Île Coco, and L'île du Sud. The settlement on Albatross was abandoned in 1988.

Historical population

editThe Saint Brandon archipelago was surveyed by British colonial authorities on 31 March 1911 as part of the Census of Mauritius. They found a total population of 110, made up of 97 men (86 non-Indian and 11 Indian) and 13 women (10 non-Indian and 3 Indian).[46] While the archipelago likely had a resident population at this point, as indicated by the 8 children under the age of 15 and the 5 people over the age of 60, there was also likely a seasonal component, with the largest population segment being men between 20 and 35.[47] 73 men worked in fishing, 11 at the guano mines and 4 were ship's carpenters.[48] Only one (male) person was recorded as having been born on Saint Brandon.[49]

In the 1921 census, the population had plummeted to just 22. There were 21 men (ages 19–48) and just one woman, a married Catholic, aged 31. A further 14 people were identified as part of the "general population", with 11 of them born on Mauritius, one on Rodrigues and two in the Seychelles. In addition, there were 3 Indo-Mauritians and 5 "other Indians" from Madras, Calcutta and Colombo.[50]

| Year | Resident | Transient | Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 35 | All were men.[51][52] | ||

| 1871 | 9 | All were men.[51][53][52] | ||

| 1881 | 6 | All were men.[51][52] | ||

| 1891 | 0 | [54][55] | ||

| 1901 | 87 | 85 men and 2 women. 54 men and one woman were from the "general population"; 29 men were Indo-Mauritians, and two men and one woman were "other Indians"[55] | ||

| 1911 | 110 | [56] | ||

| 1921 | 22 | 14 people were identified as part of the "general population", with 3 Indo-Mauritians and 5 "other Indians". 21 were men and just one was a woman.[57] | ||

| 1931 | 61 | All were men, of whom nine were married and one was an ethnic Indian. Fishing was the occupation of 59 of the men, while two were domestic servants. Most were Catholics, but one Muslim lived on the island.[58] | ||

| 1944 | 93 | All were men, two of them ethnic Indians, and the remainder of the "general population".[59] | ||

| 1952 | 136 | 124 men (one of whom was ethnically Chinese) and 12 women.[60] | ||

| 1962 | 90 | [61] | ||

| 1972 | 128 | [62] | ||

| 1983 | 137 | [63] | ||

| 2000 | 0 | 63 | 63 | No permanent residents. Only transient population.[64] |

| 2011 | 0 | No permanent residents. Transient population not reported.[65] |

See also

edit- Albatross Island, St. Brandon

- Avocaré Island

- Carl G. Jones

- Constitution of Mauritius

- Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas

- Emphyteutic lease

- France Staub

- Geography of Mauritius

- Gerald Durrell

- History of Mauritius

- Île Verronge

- Islets of Mauritius

- L'île du Gouvernement

- L'île du Sud

- List of mammals of Mauritius

- List of marine fishes of Mauritius

- List of national parks of Mauritius

- Mascarene Islands

- Mauritian Wildlife Foundation

- Nature conservation

- Outer Islands of Mauritius

- Permanent grant

- Saint Brandon Conservation Trust

- Wildlife of Mauritius

References

edit- ^ a b PRB: OIDC.

- ^ "Introduction". Central Statistics Office, Mauritius. 2001. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ "The lease of 15 of these islets expired in May 1992 and have not been renewed since then. The 15 islets are now under the direct control of the Outer Islands Development Corporation (OIDC)". oidc.govmu.org. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "The Raphael Fishing Company Ltd v The State of Mauritius and Another (Mauritius)". vLex. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "The Raphael Fishing Company Ltd v. The State of Mauritius & Anor (Mauritius) [2008] UKPC 43 (30 July 2008)". www.saflii.org. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Ministry of Environment & Sustainable Development Mauritius Environment Outlook Report 2011 (PDF). 2011. p. 223.

Blue Print for the Management of St. Brandon : A Blue Print on future economic development for St. Brandon was prepared in 2002 so as to manage and develop the islets with better land use, improvement in services, environmental protection, fisheries management, tourism development and diversification of the economy. The Blueprint has been approved by Government in 2004 and needs to be implemented. The salient issues in the Blue Print which are based on recommendations made in the World Bank Report 2001 are as follows: Declaration of St. Brandon as a Marine Protected Area. Division of the Archipelago into five distinct zones with specific recommendations for the sound management of each zone. No major economic activities to be carried out on the Archipelago except fishing within the sustainable limits of 680 tons of fish per year. No resort or hotel accommodation or supporting infrastructure such as harbours and runways to be set anywhere in St. Brandon. The Fisheries Division and the National Parks and Conservation Service to monitor at least once every year the populations of birds, turtles and fish. Restoration of the native fauna through eradication of introduced animals. Reinforcement of the Coast Guard Service on St. Brandon by the provision of patrol vessels and through training of officers.

- ^ Jean-Marie Chelin (2010). "Annee 1796". Histoire Maritime de L'Ile Maurice 1791 -1815 (in French). Tamarin. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-99949-32-71-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Plaine Magnien". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ Coral Reefs of the World Volume 2 IUCN and UNEP. UNEP. 1988. p. 212. ISBN 2-88032-944-2.

- ^ "Novaculops alvheimi Randall, 2013 - St. Brandon's sandy". fishbase.

- ^ Randall, John E. (2013). "Seven new species of labrid fishes (Coris, Iniistius, Macropharyngodon, Novaculops, and Pteragogus) from the Western Indian Ocean". Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation. 7: 1–43. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1041964. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "2024 U.S-Africa Biz Summit Takes Place in Dallas, Texas, May 6-9". allafrica.com. 5 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Saving Africa's Rarest Species at the Corporate Council on Africa". www.usafricabizsummit.com. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "1755 The Great Lisbon Earthquake and Tsunami, Portugal". www.sms-tsunami-warning.com. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "Arnhem (+1662)". Wrecksite. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Roberts DL, Solow AR (November 2003). "Flightless birds: when did the dodo become extinct?". Nature. 426 (6964): 245. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..245R. doi:10.1038/426245a. PMID 14628039. S2CID 4347830.

- ^ Anthony Cheke; Julian P. Hume (30 June 2010). Lost Land of the Dodo: The Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-4081-3305-7.

- ^ a b Jolyon C. Parish (2013). The Dodo and the Solitaire: A Natural History. Indiana University Press. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-253-00099-6.

- ^ Rijks geschiedkundige publicatiën: Grote serie. Martinus Nijhoff. 1979. ISBN 978-90-247-2282-2.

- ^ Megan Vaughan (1 February 2005). Creating the Creole Island: Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Mauritius. Duke University Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 0-8223-3399-6.

- ^ Jean Marie, Chelin (2010). Histoire Maritime de L'Ile Maurice 1791 -1815 (vol. 2 ed.). Tamarin, Mauritius. pp. 188, 189, 190. ISBN 978-99949-32-71-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "'The German Cruiser "The Wolf" Uses Saint Brandon as a transhipment point for the cargo of captured allied ships in 1917". Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (1974). Raider Wolf: the voyage of Captain Nerger, 1916-1918 by Edwin P Hoyt P150-P157. P. S. Eriksson. ISBN 978-0-8397-7067-1. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ 1921 Census, pp. cciii–ccvii.

- ^ "Saint Brandon expedition 3B7M". 3b7m.com. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Denis Piat (26 January 2024). Pirates and Pirateers in Mauritius. Editions Didier Millet. p. 130. ISBN 978-981-4385-66-4.

- ^ J. R. Bruijn; F. S. Gaastra; Ivo Schöffer (1979). Dutch-Asiatic Shipping in the 17th and 18th Centuries: Outward-bound voyages from the Netherlands to Asia and the Cape (1595-1794). Nijhoff. ISBN 978-90-247-2270-9.

- ^ Perry J. Moree (January 1998). A Concise History of Dutch Mauritius, 1598-1710: A Fruitful and Healthy Land. Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0609-8.

- ^ Anthony S. Cheke; Julian Pender Hume (2008). Lost Land of the Dodo: An Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14186-3.

- ^ "The history of Mauritius, or the Isle of France, and the neighbouring islands; from their first discovery to the present time; Page 320 by Charles Grant". Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Jean-Marie Chelin (2010). "Année 1795". Histoire Maritime de L'Ile Maurice 1791 -1815 (in French). Jean-Marie Chelin. p. 69. ISBN 978-99949-32-71-9.

- ^ "Cabalva (+1818)".

- ^ a b c The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle for 1851. Cambridge University Press. 26 January 2024. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-108-05443-0.

- ^ Various (28 February 2013). The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle for 1846. Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-1-108-05434-8.

- ^ "MV Argus 1969". wrecksite. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Norman Hooke (1989). Modern shipping disasters, 1963-1987. Lloyd's of London Press. ISBN 978-1-85044-211-0.

- ^ "longliner ran aground on the reef crest of St Brandon's Atoll". 20 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Grounded". Volvo Ocean Race official website. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ "Échouage d'un bateau de pêche: une catastrophe écologique menace Saint Brandon". 6 February 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "AU LARGE DE SAINT-BRANDON : Naufrage d'un bateau de pêche - Le Mauricien". www.lemauricien.com. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "f/v Kha Yang aground, salvage under way". FleetMon.com. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ "Alam Manis Runs aground in St Brandon". Shipwreck Log. 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Hassen Taher Seafoods". defimedia. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "LEE TSANG FISHERY CO LTD, Kaohsiung City, Chinese Taipei (Taiwan) | World Shipping Register". world-ships.com. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ "aiwanese Longliner Goes Aground on Mauritius' Saint Brandon Shoal". oceancrew.org. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ 1911 Census, p. iv, Abstracts iv.

- ^ 1911 Census, p. Abstracts xcvi, xcviii.

- ^ 1911 Census, p. Abstracts cxii.

- ^ 1911 Census, p. Abstracts cxvii.

- ^ 1921 Census, pp. 13, 15, 16, cciii–ccvii.

- ^ a b c 1901 Census, p. 168.

- ^ a b c 1881 Census, pp. 481–482.

- ^ 1871 Census, Part 2, p.2.

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1 April 1892, pp. 38, 41

- ^ a b Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 21 March 1902, p. 168

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1912, p. iv

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1921, p. 13,15,16

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1931, p. lxii–lxiii

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1944, p. 3

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1 June 1953, p. 6

- ^ Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 1962, pp. 42–43

- ^ Preliminary Results of the 1983 Population Census (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Central Statistical Office, January 1984, p. 1

- ^ 1983 Housing and Population Census of Mauritius (PDF), vol. 1, Port Louis, Mauritius: Central Statistical Office, October 1984, p. 1

- ^ Population Tables: 2000 Housing and Population Census, Port Louis, Mauritius: Central Statistical Office, November 2001

- ^ Census 2011 Atlas (PDF), Port Louis, Mauritius: Central Statistical Office, 2011, p. 1

Further reading

edit- Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 27 December 1871

- Census of Mauritius and its Dependencies (PDF), Mauritius: Census Commission for Mauritius and its Dependencies, 6 December 1881

- "Pay Research Bureau: Outer Islands Development Corporation". Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "Ministry of Local Government and Outer Islands - St Brandon". Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

External links

edit- Media related to Cargados Carajos Shoals at Wikimedia Commons

- Map of Mauritius

- Media related to Cargados Carajos Shoals at Wikimedia Commons

- Marine Protected Areas by Project Regeneration

- Marine Protection Atlas - an online tool from the Marine Conservation Institute that provides information on the world's protected areas and global MPA campaigns. Information comes from a variety of sources, including the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), and many regional and national databases.

- Marine protected areas - viewable via Protected Planet, an online interactive search engine hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC).