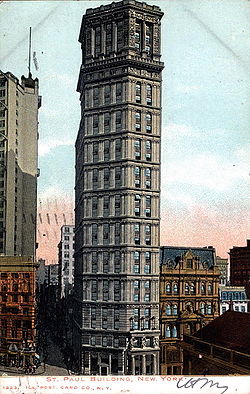

The St. Paul Building was an early skyscraper at 220 Broadway, at the southeast corner with Ann Street, in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Designed by George B. Post and completed in 1898, it was one of the tallest skyscrapers in New York City upon its completion, at 26 stories and 315 feet (96 m).

| St. Paul Building | |

|---|---|

Seen in 1907 | |

| |

| Etymology | St. Paul's Chapel |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Location | 40°42′40″N 74°00′31″W / 40.71111°N 74.00861°W |

| Address | 220 Broadway |

| Town or city | New York City |

| Country | United States |

| Construction started | 1895 |

| Completed | 1898 |

| Demolished | 1958 |

| Cost | $40 million |

| Height | 315 feet (96 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 26 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | George B. Post |

The facade, cantilevered from the superstructure, contained several sets of double-height Ionic-style colonnades, as well as a group of three caryatids designed by Karl Bitter. The foundations were dug to the level of the underlying sand due to the depth of the bedrock below. The superstructure was designed to allow easy identification and replacement of the beams. The building was occupied mostly by offices, with six elevators inside.

The building site was purchased by the Havemeyer family in 1895. The St. Paul Building was named after St. Paul's Chapel, directly across Broadway to the west. It remained in the possession of the Havemeyer family until 1943, when it was sold to Webb and Knapp and then to Chase Bank. The St. Paul Building was demolished in 1958 in order to make way for the Western Electric Building. A part of the facade, including Bitter's sculptures, remains extant at Holliday Park in Indianapolis.

Architecture

editThe St. Paul Building had 26 stories and was 315 feet (96 m) tall.[1][2] It also contained two basement levels.[3] George B. Post was the architect, Robinson and Wallace was the general contractor J. B. & J.M. Cornell was the steel contractor.[2][4] Karl Bitter designed the sculptures above the building's entrance.[2][5]

The St. Paul Building filled a five-sided lot bounded by Broadway to the west, Park Row to the northwest, Ann Street to the north, and other buildings to the east and south.[1][2][a] The lot had dimensions of 28 feet (8.5 m) on Broadway, 39 feet (12 m) on Park Row, 83 feet (25 m) on Ann Street, 54 feet (16 m) on the east, and 104 feet (32 m) on the south.[7] It was at the southeast corner of the five-pointed intersection of Broadway, Park Row, and Ann Street, and was immediately east of St. Paul's Chapel, located across Broadway. The building's address was cited as 220 Broadway.[8]

Facade

editThe western, northwestern, and northern facades were made of limestone. The articulation of these facades consisted of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a four-story base, a 16-story shaft, and a five-story capital separated from the shaft by a transitional story. The eastern and southern facades were made of brick and not ornamented. The rear (eastern) portion of the building was 22 floors tall and set back by 20 feet (6.1 m) from the lot line on Ann Street.[9]

The first four stories comprised the "base" of the building, and had rusticated blocks, with cornices above the 1st, 2nd, and 4th floors.[10] On the Broadway side, above the 1st floor, were three sculptures by Karl Bitter, titled "Racial Unity.” The figures depicted three stone atlantes holding up parts of the building, namely a Black person, a white person, and a Chinese person.[5]

Between the 5th and 20th stories, the facade was split into eight double-story sections, with Ionic-style piers between the windows supporting cornices above every even-numbered story.[8][10] The 21st story, treated as a transitional story, had engraved panels between each window. A larger cornice projected above the 21st story. The top five stories comprised the "capital" of the building, with the 22nd through 25th floors being visible from the street. Pedestals outside the 22nd story supported either triple-height engraved panels at the building's corners, or triple-height columns separating the windows on each side. The spandrel panels in the building were also elaborate.[10] The 26th floor was hidden by the parapet at the top of the building, and lit by skylights.[3][9]

Foundation

editThe bedrock under the St. Paul Building was at a depth of 86.5 feet (26.4 m).[2][3][11] The ground above the bedrock was overlaid with extremely fine, compact, clean sand, and a well on the site demonstrated that pumping out the groundwater caused minimal disruption to the sand.[11] Instead of carrying the foundation of the St. Paul Building down to the underlying rock, as with the city's other skyscrapers, the builders only excavated to the layer of sand 31.5 feet (9.6 m) deep, where the subbasement floor was to be located.[12][13][14] Test loads of up to 13,000 pounds per square foot (620 kPa) were placed on the sand and left to sink 9 to 13 inches (230 to 330 mm), after which the ground was deemed stable.[3][11][13] This was covered with a 12-inch (300 mm) layer of concrete, spread out over the entire area of the base to evenly distribute the building's weight.[11][12][14] Installed above the concrete layer were pairs of steel bases that supported either grillage or short columns carrying the cantilever girders to shore up the party walls shared with other buildings.[11][12][13] The foundation did not use piles, as in the nearby Park Row Building and 150 Nassau Street, because the sand was already highly compacted.[3]

The original plans called for hydraulic jack screws to be installed at the bottom of the columns, which could raise the entire building's 15,000-short-ton (13,000-long-ton; 14,000 t) weight. The hydraulic jacks were to be installed because the designers and engineers wanted to prevent the building from settling.[2][8][12] There were also plans to construct a "joint foundation" on the southern property line, to be shared with the property to the south. When the southern property owner decided against developing their site, the southern wall was instead reinforced via cantilevers, thus keeping the St. Paul Building's foundations independent of those of other buildings.[2][15][16] The jacks had already been ordered, so they were installed anyway.[15][16]

Features

editThe facade was cantilevered from the superstructure.[1][2] Box columns were placed behind the vertical piers of the facade.[2][15] The masonry and windows in each of the bays were supported by parallel columns and perpendicular I-beams, which in turn were cantilevered at the ends of the girders underneath the floors. This allowed easy identification and repair of corroded beams; prevented water intrusion on the facade from damaging the superstructure; and protected the St. Paul Building from fires that started in other buildings. Portal-arch bracing was used to brace the structure against the wind.[2][4] The superstructure's steel beams were painted with a special mixture three times before installation: twice at the shops where they were made, and once more at the building site. The beams below ground level were coated with asphalt. The floors were made of tile arches.[4]

The St. Paul Building had a single stair on its far eastern end. A bank of six elevators was at its western end, arranged in a quarter-circle from east to south, with an open shaft southeast of the elevators to house their hoisting apparatuses.[15][17] Two elevators served all the floors from the lobby to the 8th story; another two ran express from the lobby to the 8th story, then served all floors through the 16th; and the final two ran express from the lobby to the 16th story, then served all floors to the 26th.[9] The offices faced outward from a corridor that ran west to east between the stairs and elevators, as well as outward from the elevator lobby.[17] There were two closets on each floor.[4]

The 26th floor was used as a utility floor.[2] This floor contained the building's water tank. The building's standpipe system used an extremely high pressure, so about 333 feet (101 m) of vertical piping was used.[9] The New York City Fire Department demonstrated the strength of the standpipe in an 1899 test where the pipe burst after four minutes of operation.[18][19]

History

editConstruction and use

editPrior to the St. Paul Building's construction, the site was occupied by Barnum's American Museum,[20][21] which burned down in 1865.[22] The site was then developed as the old headquarters of the New York Herald, which was placed for sale in 1894. The Herald building was purchased by the Havemeyer family for $950,000 in January 1895.[20] That May, demolition commenced on the Herald building.[23] Post was hired by a member of the Havemeyer family to design the St. Paul Building.[2] The builders conducted the foundation tests in early 1896, with Post subcontracting engineers to ensure the consistency of the soil.[11][14] During construction, in May 1896, a girder fell off the facade and killed a passerby.[24] The St. Paul Building was completed in 1898 at a cost of $1,089,826.10 (equivalent to $40 million in 2023[b]).[7] The building was one of New York City's tallest upon its completion; only the Park Row Building, completed in 1899, was taller.[25][26]

During the early 20th century, notable tenants at the St. Paul Building included The Outlook magazine,[27] where Theodore Roosevelt was an associate editor after he served as U.S. president.[28] As early as 1919, the Havemeyers were considering selling the St. Paul Building, valued at the time at $1.49 million.[29] However, the St. Paul Building remained in the possession of the Havemeyer family until April 1943, when it was acquired by Webb and Knapp.[30] In August 1943, the Chase National Bank bought the St. Paul Building for cash. At the time it was assessed at $1.154 million, with an annual rent income of $150,000.[8][31]

Demolition

editAT&T's Western Electric division outgrew the AT&T headquarters at 195 Broadway, immediately to the southwest, in the 1950s, having made significant profits during the Cold War.[32] In 1957, Western Electric started planning its own structure diagonally across Broadway and Fulton Street, at the site of the St. Paul Building.[33] By the time demolition was underway by 1959, it was the tallest voluntarily demolished building in the world.[34] The 31-story building at 222 Broadway, which replaced the St. Paul Building, was completed in 1962.[35][36] Western Electric put 222 Broadway for sale in October 1983,[37] and it was purchased by Swiss Bank Corporation in 1987.[38]

Preservation of facade

editThe Committee to Preserve American Art was formed in August 1958 to save works of art in buildings that were planned to be destroyed, particularly the St. Paul Building.[39] The building's sculptures were valued at $150,000,[5] and the committee offered to pay for the cost of removing the sculptures, which could run up to $50,000.[5] Several organizations and entities in the United States—including Columbia University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the United Nations, and the cities of Indianapolis, Indiana, and Rochester, New York—made requests for the sculptures.[39][40][41] Another proposal called for moving the sculptures to Bitter's home country of Austria.[42] Because of the great demand for the sculptures, Western Electric agreed to save them.[43]

Ultimately, Indianapolis won the sculptures in November 1958.[44] Elmer Taflinger, described as the "grand old man of Indiana art", had presented a plan to move the sculptures and part of the St. Paul Building's lower facade to Holliday Park. Before Indianapolis won the sculptures, Taflinger had proposed moving them to Indiana University Medical Center or to a bridge over the White River.[41] The statues were removed in early 1959.[45] After sitting in boxes for two years,[46] the sculptures were installed in Holliday Park in 1960, atop columns made specifically to house them, as part of a grouping called The Ruins.[47] However, the sculptures and facade then became dilapidated, and by 1970, Western Electric had expressed regret at the decision to give the sculptures and facade to Indianapolis.[46] The facade and the rest of The Ruins were cleaned up and formally dedicated in 1973. After another period of deterioration, the St. Paul Building facade was restored again in 2016.[41][46]

Critical reception

editReviews of the St. Paul Building were mostly negative.[9] One critic characterized it as having "perhaps the least attractive design of all New York's skyscrapers",[1][9][48] second only to the Shoe & Leather Bank Building at Broadway and Chambers Street.[48] The Real Estate Record and Guide stated in 1897 that "in execution it has the look of arbitrariness and caprice which is always unfortunate in a work of architecture, and which is, perhaps, especially injurious in a tall building".[49] Another critic for the Real Estate Record and Guide, writing in 1898, characterized the St. Paul and Park Row Buildings as "two domineering structures [that] swear at each other". The unnamed critic characterized the top stories of the St. Paul Building as well designed, compared to the Park Row Building's cupolas. However, the critic also lambasted the "impossible 'realism'" of Bitter's figures on the St. Paul Building's facade, as contrasted with J. Massey Rhind's sculptures on the Park Row Building's facade.[50][51] Critic Jean Schopfer called the St. Paul Building "mediocre", as compared with other skyscrapers like the "detestable" Park Row Building or the "interesting" American Surety Building.[52]

Post himself was opposed to skyscrapers of over 300 feet (91 m), even including the St. Paul Building, due to his concerns that wind and fire could overcome such tall structures.[53] As he told The New York Times, he ironically had been involved in two buildings that had introduced skyscraper innovations: the Equitable Life Building, the first to use elevators, and the New York Produce Exchange building, the first to use fireproof floors upon iron cages.[53] The Real Estate Record commented that the St. Paul Building had offered Post "the occasion to say 'I told you so' at his own expense".[54][21]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ Park Row forms a chamfer in the corner of Broadway and Ann Street. The chamfer is preserved in the lot line of the modern 222 Broadway.[6]

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

Citations

edit- ^ a b c d "St. Paul Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Landau & Condit 1996, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e Engineering News 1896, p. 310.

- ^ a b c d Engineering News 1896, p. 312.

- ^ a b c d "Everybody wants the statues". New York Daily News. October 26, 1958. p. 778. Retrieved August 8, 2020 – via newspapers.com .

- ^ "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, p. 426.

- ^ a b c d "26-Story Building in Downtown Sale; 220 Broadway Bought by Chase National Bank for Cash and 41 West 34th St". The New York Times. August 17, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 239.

- ^ a b c d e f "Preliminary Foundation Tests for the St. Paul Building". Engineering Record. 33: 388. May 2, 1896.

- ^ a b c d "Hydraulic Jacks as Part of a Permanent Foundation". American Architect. 52: 1–2. April 18, 1896.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 425.

- ^ a b c Engineering News 1896, pp. 310–311.

- ^ a b c d Engineering News 1896, p. 311.

- ^ a b Real Estate Record 1897, p. 963.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, p. 240.

- ^ "Fire Test on a Sky Scraper; Stand Pipe in the St. Paul Building Burst After Stream Had Been Operating Four Minutes". The New York Times. March 13, 1899. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Stand-pipe Bursts: a Fire-fighting Test at the St. Paul Building Spoiled". New-York Tribune. March 13, 1899. p. 5. Retrieved August 4, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "The Real Estate Field; Why Record Statistics Are Without Value". The New York Times. January 6, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Real Estate Record 1897, p. 962.

- ^ "Disastrous Fire; Total Destruction of Barnum's American Museum. Nine Other Buildings Burned to the Ground". The New York Times. July 14, 1865. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Must Be Quickly Razed; Seventy Days for Destruction of the Old Herald Building". The New York Times. May 1, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Killed at the St. Paul Building". The New York Times. May 23, 1896. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020 – via newspapers.com .

- ^ "The Tallest of Modern Office Buildings". Scientific American. 79 (24): 410. December 24, 1898.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Park Row Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 16, 2005. p. 6. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Steel Inquiry to-day in Outlook Office; Special Session of Government Quest for a Trust to be Held to Examine Roosevelt". The New York Times. January 22, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1909). Alfred Emanuel Smith (ed.). New Outlook. Outlook Publishing Company, Inc.

- ^ "Havemeyers Ready To Sell Valuable Realty Holdings: St. Paul Building on Broadway and Block on Prince Street Said To Be Under Sale Negotiations". New-York Tribune. October 8, 1919. p. 23. Retrieved August 6, 2020 – via newspapers.com .

- ^ "Havemeyer Estate Sells 3 Holdings; Webb & Knapp Buy Buildings on Lower Broadway, Fifth Ave. and Liberty St". The New York Times. April 1, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Webb & Knapp Sell Broadway Corner Holding: Chase Bank Buys 26-Story St. Paul Building, Rounding Out Blockfront Site". New York Herald-Tribune. August 17, 1943. p. 26A. Retrieved August 4, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "American Telephone and Telegraph Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 25, 2006. p. 8. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ "Bell System Unit Plans Own Home; Western Electric Co. Takes Options on Blockfront on Broadway at Fulton". The New York Times. September 18, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ Saffron, Paul (June 11, 1959). "Smashingest Hit in Town: Boom in House Wrecking". New York Daily News. p. 738. Retrieved August 8, 2020 – via newspapers.com .

- ^ "New Western Electric Building Blends With Diverse Neighbors; New Building Is a Good Neighbor". The New York Times. August 26, 1962. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Western Electric Building". Emporis. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "A.T.& T.; Building". The New York Times. October 26, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Garbarine, Rachelle (April 8, 1992). "Real Estate; Downtown, New Offices Are Renting". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Knox, Sanka (August 10, 1958). "Threatened Art Finds a Champion; Committee Is Set Up Here -- St. Paul Building's Stone Figures Will Be Saved". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Knox, Sanka (November 8, 1958). "A City, 3 Colleges Ask for Statues; Seek Stone Figures to Be Salvaged From St. Paul Building on Broadway". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Dawn (January 25, 2019). "How 'The Ruins' at Holliday Park took decades to complete". Indianapolis Star. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Meyer (December 2, 1957). "About New York; Karl Bitter's Statuary on St. Paul Building May Be Offered Austria, Which Exiled Him". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Meyer (November 7, 1958). "About New York; The Future of Heroic Statues of '96 to Be Settled by Architecture Group Today". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Old Broadway Statues Will Go to Indianapolis". The New York Times. November 20, 1958. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Big Letdown". New York Daily News. March 6, 1959. p. 58. Retrieved August 8, 2020 – via newspapers.com .

- ^ a b c "Karl Bitter, Elmer Taflinger, and the Holliday Park Ruins - All Things Indianapolis History". Historic Indianapolis. May 20, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "The Ruins" (PDF). Friends of Holliday Park. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Tall Buildings of New York". Munsey's Magazine. 18: 841. March 1898.

- ^ Real Estate Record 1897, p. 964.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 256.

- ^ "The Park Row" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 62 (1589): 287. August 27, 1898 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Schopfer, Jean (1900). "American Architecture from a Foreign Point of View: New York City". Architectural Review. 7: 30.

- ^ a b "Limit of High Buildings; Views of Mr. Post, Personally Opposed to Sky-Scraping Structures". The New York Times. July 14, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 241–242.

Sources

edit- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- "The Most Modern Instance" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 59 (1025): 962–964. June 5, 1897 – via columbia.edu.

- "The St. Paul Building, New York City". Engineering News. 35: 310–312. May 7, 1896.

External links

edit- Media related to St. Paul Building at Wikimedia Commons