The St. Kitts bullfinch (Melopyrrha grandis), known locally as the mountain blacksmith, is a possibly extinct songbird species of the genus Melopyrrha which was endemic to the island of Saint Kitts.

| St. Kitts bullfinch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Preserved specimen at Naturalis Biodiversity Center | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thraupidae |

| Genus: | Melopyrrha |

| Species: | M. grandis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Melopyrrha grandis (Lawrence, 1881)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Loxigilla portoricensis grandis | |

Taxonomy

editIt was previously considered conspecific with the Puerto Rican bullfinch (Melopyrrha portoricensis), from which it could be distinguished by its larger size, glossier feathers, and more extensive breast patch.[2][3]

Distribution

editIt is endemic to Saint Kitts, where it has a highly restricted range; it may have previously had a wider range, inhabiting at least Nevis and Sint Eustatius, which were both connected to Saint Kitts during the last glacial maximum, but no fossil specimens are known from there. It could have also inhabited Antigua and Barbuda, but no specimens are known from there either.[4]

Possible extinction

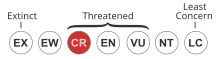

editBy 1880, it was only known from the montane forests of Mount Liamuiga (then Mount Misery), although it was reported to be "not uncommon" there. However, for many years, this report was known to be the last record of the species, as following the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane and Hurricane Four, there were no reports of the species, and it was thought to have been driven to extinction. However, a single specimen was collected in July 1929 by Paul Bartsch and preserved in the Smithsonian, with the specimen remaining overlooked until 1984, when it was described by Storrs L. Olson with the description published by David Steadman in 1997. Bartsch's collection of a specimen is unusual, as while the bird would have presumably remained extremely rare and hard to collect by this time, Bartsch's field notes indicated a brief and perfunctory visit to the island, which would likely be inadequate to collect such a rare species. No other confirmed sightings or specimen collections have been made since 1929, and the species is considered presumably extinct.[2][4] However, the IUCN Red List considers the bird Critically Endangered on the basis of "...unconfirmed records of the species within its presumed range, whilst sufficient analysis on recent sound recordings are yet to be conducted. As such, and in the absence of conclusive evidence for its disappearance, it is precautionarily assumed that a small population may persist..."[1]

The exact causes of its decline have been disputed. James Bond initially proposed that the species had been heavily reduced in number by the introduced vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus). However, this hypothesis was disputed, as its sympatric cousin, the Lesser Antillean bullfinch (Loxigilla noctis), which presumably had similar habitat requirements, survived disturbance by the same monkeys, and M. grandis is thought to have lived at higher altitudes where vervet monkeys were uncommon.[2]

An alternate theory, proposed in 1977, was that the decline was due to natural causes, with competitive exclusion by L. noctis forcing M. grandis to be limited to the restricted habitat at higher altitudes, thus leaving it at much bigger risk of being wiped out by the hurricanes of 1899; however, this account was made before the description of Bartsch's specimen. In contrast, Olson proposed in 1984 that M. grandis formerly had a much wider range throughout the island, potentially even being adapted to drier lowland areas, and was forced into the suboptimal montane habitat by heavy habitat destruction for agriculture in the lowlands, with such activities being practiced for over 3 centuries by the time that the bird was last recorded. As the bird's habitat was not optimal, it was left at much greater risk of extinction from a variety of factors, although the exact factors have not been elucidated.[2][4]

Possible survival

editDespite the lack of reliable sightings for over a century, it is possible that the species may still be extant due to its elusive nature, as well as potential sightings in 1993, 2012, and 2021, which have been considered reliable by BirdsCaribbean.[5] Although several ornithological surveys were taken after Bartsch's sighting, with none finding the species, interviews with the surveyors found that most of the surveys were too short or performed in poor weather to be an adequate search for the bird.[6]

In 1993, a potential sighting of the species was recorded by Saint Kitts' most eminent naturalist, Campbell Evelyn. Evelyn and his wife, Joyce, were hiking near the Bloody River when they spotted a bird matching the description of the species, being almost entirely black with red on top of the head and on the throat below the chin. The bird was also much larger than the Lesser Antillean bullfinch, which they were both familiar with, and it thus could have been a St. Kitts bullfinch.[7] On November 16, 2012, coincidentally 1 day after Evelyn's passing, a Puerto Rican naturalist, Alejandro Sanchez, who was familiar with the Puerto Rican bullfinch, reported hearing a bird call similar to that of a Puerto Rican bullfinch high in the tree canopy of Mt. Liamuiga; however, despite cameras being at the ready, the bird did not show itself. The report of the bird's call was also confirmed by one of Sanchez's companions.[8] In 2021, a scientific experiment by Saint Kitts' Department of the Environment recorded a sonogram of a bird song that could potentially be that of M. grandis, which requires further investigation.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International. 2022. Melopyrrha grandis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T216918514A217577217. Accessed on 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Raffaele, H. (1977). "Comments on the extinction of Loxigilla portoricensis grandis in St. Kitts, Lesser Antilles" (PDF). Condor. 79 (3): 389–390. doi:10.2307/1368023. JSTOR 1368023.

- ^ Hume, Julian P.; Walters, Michael (2012), "Extinct Birds", Extinct Birds, Poyser, pp. 17–326, doi:10.5040/9781472597540.0007, ISBN 978-1-4725-9754-0

- ^ a b c Steadman, D. W. (1997). "The Birds of St. Kitts, Lesser Antilles" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 33 (1–2): 15–16. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

- ^ "The Caribbean has Two New Bird Species . . Sadly, They May Both be Extinct". www.birdscaribbean.org. 2021-07-08. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ Wiley, Orlando H. Garrido and James W. (2003). "The Taxonomic Status of the Puerto Rican Bullfinch (Loxigilla Portoricensis) (Emberizidae) in Puerto Rico and St. Kitts". Ornitologia Neotropical. 14 (1): 91–98.

- ^ Horwith, Bruce (1999). A biodiversity profile of St. Kitts and Nevis. Island Resources Foundation. OCLC 786005670.

- ^ "Is the St. Kitts Bullfinch Still Alive?". Birds of St Kitts Nevis. 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2021-07-29.

- ^ "St. Kitts Bullfinch Granted Full Specie Status—Although extinct for almost 100 years!!!". Birds of St Kitts Nevis. 2021-06-27. Retrieved 2021-07-29.