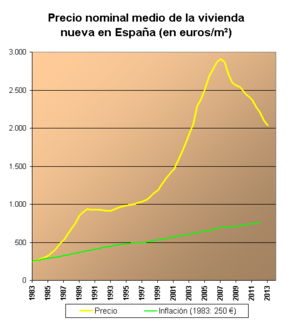

The Spanish property bubble is the collapsed overshooting part of a long-term price increase of Spanish real estate prices. This long-term price increase has happened in various stages from 1985 up to 2008.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] The housing bubble can be clearly divided in three periods: 1985–1991, in which the price nearly tripled; 1992–1996, in which the price remained somewhat stable; and 1996–2008, in which prices grew astonishingly again. The 2008–2014 Spanish real estate crisis caused prices to fall. In 2013, Raj Badiani, an economist at IHS Global Insight in London, estimated that the value of residential real estate has dropped more than 30 percent since 2007 and that house prices would fall at least 50 percent from the peak by 2015.[10] Alcidi and Gros note; “If construction were to continue at the still relatively high rate of today, the process of absorption of the bubble would take more than 30 years”.[11]

Existence of the bubble

editThis article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2023) |

Although there is not an exact definition of a speculative bubble, in the case of the Spanish bubble, differences between the average increase of the CPI and wages of 3% and the annual increases of the price of living up to 17% were evident indicating the price of housing increased 6 times more quickly than wages and the average CPI.[citation needed]

In August 2007, the U.S. real estate bubble burst, following the subprime mortgage or junk mortgage crisis. A little after[when?] the Spanish National Institute of Statistics announced the strong decrease of buying and selling of housing (27% in the first trimester of 2008) and the contraction of mortgages (25% in January 2008), this is considered the moment the Spanish bubble popped.[citation needed]

Construction companies, the main beneficiaries of the increase in prices, used to deny the existence of the bubble, clarifying the interested "myth", as well as other sectors directly tied to the construction business, for which a bubble did not exist, but was simply a "real estate boom". On their behalf, the sectors in disagreement with the economic situation, more connected to the consumers, mainly affected by the increase of prices and the difficulties of access to housing, insisted in valuing the same data in the opposite sense, the same that other groups framed as a social critique and the Green Movement.

The future evolution of a market influences the real behavior of an individual. If many potential buyers estimate that a future fall in prices is nearing, they can opt to wait for this to occur in order to buy. This provokes that the current demand decreases and, therefore, the real prices fall. The same procedure would take place in the inverse if people were waiting for an increase.

On the other hand, the lack of transparency that characterizes the housing market in Spain impeded making exact evaluations of the situation: while one entity sent calm and alarming messages at the same time, the statistics never were systematic and were characterized by dispersion, when they were not simply contradictory, but remaining part of the hidden tax real estate market, upon moving in part with black money or in a form of corruption. In that sense, some specialists denounced even a campaign of a lack of transparency and secrecy of the means of communication that, based in economic interests, would have avoided mentioning the true nature of the boom in housing costs.

In any case, in the first months of 2008 the strong deceleration of the Spanish housing market already permitted some economists like Alan Greenspan, the former chair of the Federal Reserve, to talk about a speculative bubble and its burst. In that same sense, in April 2008 construction companies and promoters themselves recognized that there had been a "large drop in prices and (...) exploded the consumers of the market", implicitly recognizing an overvaluation of real estate assets, forecasting a panoramic shadow both over the sector and the entire Spanish economic structure. In 2009, still nobody had doubted that an enormous speculative real estate bubble had exploded around the world, with particular virulence in Spain, which as a result saw an immersive deep economic recession.

According to a 2005 cable of the United States embassy in Madrid, the symptoms of a very considerable overvaluation could already be warned against, citing as its causes the nonexistence of a counterbalance of the rent market under an unfavorable legislation that was not likely to change under internal pressures in the main parties, according to the same cable. Also, it speculated success when the bubble exploded and the financial situation intensified, the government that would have been in power would have summoned early elections.

General evaluations of the situation

editIf the facts about the real estate market were already accepted, by the different actors, it would not always be in agreement with the evaluation that makes such data. The same Bank of Spain rejected the idea that would have revolved around a speculative bubble:

The results of the work carried out in the housing market did not support, according to the Bank of Spain, the hypothesis of equilibrium or a bubble, but rather reinforced the confusion that the situation of the Spanish real estate market was characterized at the end of 2004 by an over-valuation of suitable housing with a gradual uptake of the found discrepancy among the observed prices and the explained prices by its fundamental in the long term.[12]

However, the official reports of that entity also recognized the over-valuation of real estate assets, and already in the year 2002 alerted about a possible depreciation of housing. In 2003, García Montalvo published one of the first articles about the formation of a real estate bubble in Spain.

Those who denied the existence of a speculative bubble, and at most accepted a small over-valuation of assets, argued for the good state of the Spanish economy, the employment and sustained growth data, and very small default rates, attributing the growth of prices to a pressure of demand.

On the other extreme were the critiques of those who estimated that things were occurring before a real estate bubble of unpredictable consequences:

A colossal speculative [real estate] bubble has been developing for many years already, which has been characterized by the Economist (June 18, 2005) as a major speculative process in the history of capitalism.

In general, from the critical positions it was affirmed that the dependence of the Spanish economy on the construction industry, as well as excessive debt, could have provoked an economic recession in the long term, especially with the rise in interest rates, that eroded domestic consumption and raised the unemployment rate and the default levels, finally leading to a devaluation of real estate assets.

Dynamics

editHome ownership in Spain is above 80%. The desire to own one's own home was encouraged by governments in the 1960s and '70s, and has thus become part of the Spanish psyche. In addition, tax regulation encourages ownership: 15% of mortgage payments are deductible from personal income taxes. Furthermore, the oldest apartments are controlled by non-inflation-adjusted rent controls[13] and eviction is slow, thereby discouraging renting. Banks offered 40-year and, more recently, 50-year mortgages.

As feared, when the speculative bubble popped, Spain became one of the worst affected countries. According to Eurostat, over the June 2007-June 2008 period, Spain was the European country with the sharpest plunge in construction rates.[14] In 2008, new construction came virtually to a halt, but prices were initially relatively stable with sellers reluctant to offer large discounts. The national average price as of late 2008 was 2,095 euros/m2.[15][16] Actual sales over the July 2007-June 2008 period were down an average 25.3% (with the lion's share of the loss arguably happening in the 2008 tract of this period). Some regions have been more affected than others: Catalonia was ahead in this regard with a 42.2% sales plunge while sparsely populated regions like Extremadura were down a mere 1.7% over the same period.[17]

Unlike much of the United States, but like most European countries, Spain does not recognize mortgage loans as nonrecourse debt. Since property prices dropped enough for most foreclosures to only account for 60% of the loan, those evicted have large debts for property they no longer own.[18]

Figures

editPrices and number of houses built

editAccording to the reports of the Bank of Spain, between 1976 and 2003, the price of housing in Spain doubled in real terms, which means, in nominal terms, a multiplication of 16. In the period for 1997—2006, the price of housing in Spain had risen about 150% in nominal terms, equivalent to 100% growth in real terms. It is stated that from 2000 to 2009, 5 million new housing units had been added to the existing stock of 20 million.[19] In 2008, the real estate market started to drop fast, and house prices decreased dramatically by 8% in that year.[20] In the period for 2007-2013, Spanish house prices fell by 37%.[21] Each year almost a million homes were built in Spain, more than in Germany, France, and England combined.[22]

Real estate debt

editOne of the main effects of this situation is the growth of household debt. Since usually the purchase of housing, whether to live in or to invest, is financed with mortgage loans, the price increase implies an increase in debt. Spanish consumer debt tripled in less than ten years. In 1986, debt represented 34% of disposable income, in 1997 it rose to 52%, and in 2005 it came to 105%. In 2006, a quarter of the population was indebted with maturities of more than 15 years.[23] From 1990 to 2004, the average length of mortgages increased from 12 to 25 years.[24] The Bank of Spain reported that household savings in 2006 had been overwhelmed by debt.[25] In fact, the Bank of Spain has warned each year about the high rates of indebtedness of Spanish households,[26] which according to the institution was unsustainable. Private debt stood at 832.289 billion euros at the end of 2006, an increase of 18.53% year-on-year, and reached 1 trillion euros by the end of 2010.[27] The Bank of Spain also warned on the excessive indebtedness of the construction industry.[28]

The President of the Chambers of Commerce of Spain, Javier Gómez Navarro, said at an event organized by the Association of Financial Journalists, entities "never recover" 30% of the debt owed to the housing sector. According to the Bank of Spain, this debt amounted to 325,000 million euros; as of December 2009, it totaled 96.824 million in bad loans.[29] The president of the Chambers regretted that the Spanish financial system did not admit the impact of the crisis on their assets; the Bank of Spain affirmed that it was the responsibility of the whole financial sector: "In Spain, it was never wanted to recognize that the financial system was not in good shape, as this would have forced the banking sector to start re-capitalising policies. The goal of the state's policy has so far been to gain time, to start a mild bank recapitalisation, but time is now running out".[30]

According to R.R. de Acuna & Asociados, a real-estate consulting firm, more than half of the country’s 67,000 developers can be categorized as “zombies”, having liabilities that exceed their assets and only enough income to repay the interest on their loans.[31] According to the Bank of Spain, the rate of household loans in doubt among the total amount of credit increased from 0.8% in 2005 to 6.2% in 2011.

See also

editSpanish

edit- Great Recession in Spain

- Savings bank (Spain)

- Unemployment in Spain

- 2008–2014 Spanish real estate crisis

World

editReferences

edit- ^ La burbuja inmobiliario-financiera en la coyuntura económica reciente (1985-1995).ISBN 978-84-323-0913-7.

- ^ Azumendi, Eduardo (29 June 2009). "La otra burbuja inmobiliaria". El País (in Spanish). Grupo Prisa. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Rullan, Onofre; Artigues, Antoni A. (1 August 2008). "Estrategias para combatir el encarecimiento de la vivienda en España. ¿Construir más o intervenir en el parque existente?". Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish). XI (245). Universidad de Barcelona: 28. ISSN 1138-9788. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ invertia.com; Mapa de la sobrevaloración de la vivienda en España Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine - Invertia

- ^ Precios históricos vivienda España Archived 2011-04-18 at the Wayback Machine - Ecobolsa

- ^ La depresión industrial augura el fin de la burbuja en el sector servicios - Libertad Digital

- ^ La burbuja inmobiliaria ha inflado el precio de las viviendas un 40 por ciento - El Imparcial

- ^ Los precios de la vivienda y la burbuja inmobiliaria en España - Instituto Juan de Mariana

- ^ En los últimos 17 años el precio de la vivienda en España se ha multiplicado por cinco - Consumer

- ^ Smyth, Sharon; Urban, Rob (2013-03-20). "Spanish Banks Cut Developers as Zombies Dying: Mortgages". Bloomberg.

- ^ "The Spanish hangover". 15 April 2012.

- ^ elEconomista.es. "Economía/Vivienda.- El Banco de España vaticina una absorción gradual de la sobrevaloración en el mercado de vivienda - elEconomista.es". www.eleconomista.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ Expósito, Antonio A. (4 November 2005). "Todo lo que tienes que saber sobre los alquileres de renta antigua". jublio.es (in Spanish). Júbilo Comunicación, S.L. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Construction output down by 0.6% in the euro area" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ "Más de 900.000 viviendas construidas en los años del 'boom' inmobiliario están vacías - Cotizalia.com". www.elconfidencial.com. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ "Recent history of the Spanish residential property market". Global Property Guide. 5 February 2021.

- ^ "La venta de viviendas cae un 42% en Catalunya en un año, el mayor porcentaje del Estado". Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Hogan, Caelainn (14 November 2011). "Spanish property bubble fallout continues with evictions, debt and fear of homelessness". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Bardhan, A., Edelstein, R. & Kroll, C. (2011), "The Financial Crisis and Housing Markets Worldwide" in Global Housing Market: Crises, Policies, and Institutions

- ^ "Spain's Property Crash: Builders' Nightmare", 2008, The Economist

- ^ Karaian, J. 2013, The Pain in Spain, Quartz

- ^ "topspanishhomes.com". ww38.topspanishhomes.com. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ "El tsunami urbanizador", pág 24 y sig.

- ^ "Spain's Booming Housing Market And The Uncertain Future". Archived from the original on 2012-12-06. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- ^ Diario El Mundo: El pago de deudas se 'comió' en 2006 todo el nuevo ahorro de las familias españolas.

- ^ Año 2003: el Banco de España alerta..., Año 2004: el Banco de España alerta..., "Año 2006: el Banco de España alerta..." Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ El Periódico de Aragón. Archived 2010-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Alerta del Banco de España a las contructoras", El Confidencial

- ^ "La deuda del ladrillo castigará a la banca, según las Cámaras de Comercio", El País, March 10, 2010

- ^ "Gómez Navarro cree que los bancos pueden 'quedarse' con el dinero del ICO" Archived 2011-12-28 at the Wayback Machine Intereconomía

- ^ Smyth, Sharon; Urban, Rob (2013-03-20). "Spanish Banks Cut Developers as Zombies Dying: Mortgages". Bloomberg.