Enslaved labor on United States military installations was a common sight in the first half of the 19th century, for agencies and departments of the federal government were deeply involved in the use of enslaved blacks.[1] In fact, the United States military was the largest federal employer of rented or leased slaves throughout the antebellum period.[2][3] In 1816, a visitor to the Washington Navy Yard wrote that master blacksmith, Benjamin King, estimated daily expense for a slave as twenty-seven cents and noted how lucrative the business had become. According to King, Navy was paying eighty cents per day for black workers while white blacksmiths were paid $1.81 per diem.[4] Further south on April 27, 1830 at Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard, civil engineer Loammni Baldwin, transmitted a detailed report showing the "great economy of employing slaves" on the new dry dock. Baldwin by comparing the average cost of free white, stone masons with enslaved black hammers, lauded the saving gained by having blacks perform the work at 72 cents per day in comparison to white stone mason's paid 2.00 per day.[5] An English visitor and author, Lady Emmeline Stuart-Wortley, writing in the late 1840s, noted the prevalence of slave labor at the Washington Navy Yard: "We saw a sadder sight after that, a large number of slaves, who seemed to be forging their own chains, but they were making chains, anchors, &c., for the United States Navy."[6]

George Teamoh (1818 to after 1887), a former enslaved laborer, ship caulker and carpenter toiled at the Norfolk Navy Yard and Fort Monroe in the 1830s and 1840s.[7]

Teamoh later wrote of his years of unrequited labor at federal shipyards and forts: "The government has patronized, and given encouragement to Slavery to a greater extent than the great majority of the country has been aware. It had in its service hundreds if not thousands of slaves employed on government works."[8]

Today, the history of the United States government's rental of slaves on federal installations still attracts "less scholastic analysis than other aspects of slavery."[9] Indeed, historians have primarily focused their research on the labor and intensive plantation economy of the South.[10] In the formative years of the nineteenth century however, the federal use of enslaved labor was often the subject of public attention, discussion and commentary, with both slaveholders and critics voicing strong opinions. Recent scholarship has confirmed that blacks, both enslaved and free, comprised a significant and vital source of labor for military, installations.[11][12][13][14][15]

Early federal use of slave labor

editFederal employment practices mirrored society, most especially in the slave holding Southern states and territories.[16] The patterns for the federal use of enslaved labor were set early. The prevalence of slavery in the new federal city of Washington, where in 1800, nearly forty percent of white householders were slaveholders, was remarked on by many early visitors such as Massachusetts Congressman Thomas Dwight (politician). Dwight writing in 1803 complained, there was "no one thing of which the people universally in this part of the Country are so fond of as owing slaves." He marveled that even the poor, invested in slaves, but noted, they recouped their money by "hiring out".[17] In the new District of Columbia, hiring out was a tradition older than the city, beginning in 1792, the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners, charged with overseeing the construction of the first public buildings, began hiring construction workers; they also quickly made the decision to hire enslaved laborers.[18] On average, the Commissioners hired 50 to 100 slaves each year.[19] The Commissioners, composed solely of slaveholders, conceived of enslaved labor as "a very useful check & kept our Affairs Cool"; a useful check, that is, on the wage demands of free laborers.[20] In the 1790s, District owners were paid $60 to $70 a year for the rental of their bondsmen, the same wage paid unskilled white laborers. The Commissioners' decision to hire blacks caused no public comment in 1792, for enslaved labor was a legally recognized and sanctioned institution.[21] This pattern continued with the establishment of new federal naval shipyards such as the Washington Navy Yard in 1799, Norfolk Navy Yard in 1801 and Pensacola Navy Yard in 1826.As construction of the White House slowed, prominent slaveholders like James Clagett, George Clark, Samuel N. Smallwood and William B. Magruder began to supply their enslaved craftsman and laborers to the Washington Navy Yard.[22][23] Similar utilization of enslaved labor has also been discerned in United States Army installations such as Fort Zachary Taylor 1845 and Fort Jefferson 1846.[24][25]

Nature of the documents

editDemographic data for civilian employment in military installations situated in the middle and southern states is often incomplete, confusing and difficult to locate. In addition, the federal government did not with rare exceptions own slave's, they instead, leased or hired bondsmen from local slaveholders. Consequently, as one distinguished historian of slavery has cautioned slave "hiring practices were not based upon open contractual negotiations but unwritten gentleman's agreements which have only been discovered by searching for those little incidents or small moments where explanation in writing was demanded."[26] Searching for enslaved and free blacks, in federal military and civilian personnel data can be daunting.[27]

First most early employee records such as musters and payrolls were created solely for financial purposes and rarely identify race or enslaved status.[28] For a good example of one that does see thumbnail of 1829 payroll for Pensacola Navy Yard. Most of these records, still must be viewed at the National Archives Washington D.C. as they have yet to be digitized or transcribed. There are large gaps in the documentation for instance payrolls for the Washington Navy Yard prior to 1840 are only available for the years 1808, 1811, 1819, and 1829 and just the 1808, 1811, and 1829 rolls explicitly list some employees as enslaved and slaveholders.[29] As one expert on slavery in early Washington D.C. succinctly put it, the District's first leaders had "a knack for ignoring slaves in their correspondence."[30] The surviving payroll and muster documents for Norfolk Navy Yard are even more meager with one roll from 1819 and a few separate payroll sheets from the 1840s, due to the destruction of early payroll and muster records in the Civil War.[31] Second the majority of naval and army musters and payrolls have not survived, many sadly falling victim to time, neglect and fire. Third as criticism and objections to enslaved labor mounted, particularity after 1820, military officers and senior civilians who were slaveholders took full advantage of so-called "gentleman's agreements" in naval shipyards and army installations, by entering enslaved individuals (e.g. Michael Shiner, see Jan 1827 Washington Navy Yard muster of the ordinary, in thumbnail below.) on to military muster rolls as "ordinary seamen" or "common laborer" to avoid congressional oversight.[32][33] Most record keepers at these federal installations as slaveholders were not neutral.[34] Another source of documentary evidence are the letters from installations commanders written specifically in response to inquiries from the Secretaries of the Army and Navy on questions of black employment for example, see 1808 letter of Commodore Thomas Tingey to Secretary of the Navy in thumbnail below and 1845 letter of Commodore Jesse Williamson to Secretary of the Navy, regarding enslaved labor at Norfolk Navy Yard.[35] Lastly, there are autobiographical accounts of Charles Ball, Michael Shiner, George Teamoh, and Thomas Smallwood that chronicle what life was like for those enslaved on federal military installations.

Because of the problems with the data mentioned above and the large gaps in the documentation, the exact number of slaves working on military installations will probably never be fully known. However, the following short overviews of slavery at the five selected military installations below provide some indication of the current state of knowledge and approximate size and nature of the enslaved workforce at the respective installations. This is concluded with brief history of the evolution of federal and military policies and practices which governed the administration of enslaved labor.

Washington Navy Yard

editEstablished in 1799, Washington Navy Yard was the first federal naval yard to use enslaved labor. This shipyard was where many of the Department of the Navy labor policies and practices regarding black employment were first instituted. Some of the same slaveholders who had supplied bondsmen to District of Columbia Commissioners, later hired their enslaved laborers to the new federal shipyard.[36][37] These policies and practices later became models for other federal shipyards and military installations. For the first thirty years of the 19th century, it was the District of Columbia's principal employer of enslaved African Americans. Their numbers rose rapidly and, by 1808, made up one-third of the workforce. The navy had quickly come to rely on enslaved labor. On 18 May 1808, Captain John Cassin wrote the Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith to plea for the retention of slaves.[38]

Understanding it is the intention of the Secretary of the Navy to discharge all Slaves employed in this Yard I beg leave to show there are but very few white men in this Neighborhood that can be found to fill the places even for one fourth higher wages, We have also in the Black Smith Shops thirteen firemen consequently they require higher Thirteen independent of the Anchor Shops which also require Six Blowers at 85 cents per day should these men now employed be discharged we should compelled to bank off six fires and turn these six firemen as strikers from 1.50 to 1.70 two White men left the Shop last week on account of the wages they received 100 D per day and were not satisfied is also necessary we have from three to five Laborers to attend the Calkers (Caulkers) one to attend the stuff the others to clean before the Calkers and whose wages have not exceeded one half the Calkers the former belonging to the men in the City but unfortunately free to say no.

Cassin's reluctance to curtail the use of enslaved labor reflects the prevalence of the rental of bondsmen in the various shops and aboard naval ships in ordinary as seamen, cooks, and laborers. The creation of the navy yard combined with employment precedents set by the District Commissioners; may well have inspired many small slaveholders to purchase additional slaves. The WNY 1808 muster illustrates that slave rentals were lucrative; allowing naval officers to supplement their pay by drawing the wages and rations of their enslaved "servants". Commodore Thomas Tingey endorsed this practice and pleaded with the Secretary Smith, to continue "this customary indulgence".[39] During this era the navy yard was "a favorite place to rent out slaves," and to sell them; but also became a recognized center of resistance.[40]

As early as 1815 the Board of Navy Commissioners (BNC) complained of "maimed & unmanageable slaves". Among these "unmanageable" were numerous navy yard runaways.[41] In 1812, one young navy blacksmith helper David Davis, made his second bid for freedom by running for Baltimore.[42] Likewise another "servant" John Howard, enslaved to Commandant, Thomas Tingey, fled north to Boston on 28 December 1819 where he was seized by slave catchers. In dramatic armed response, a group of African Americans, attempted to secure his freedom.[43] Some years later in 1825 Nathan Brown, a young navy yard anchor smith, ran away to the new black Republic of Haiti.[44] Due to its proximity to a large population of free blacks, and a few sympathetic whites, some enslaved workers like Michael Shiner at Washington Navy Yard were able to utilize the constrained legal system to contest their enslaved status.[45][46] A benchmark case was that of Joe Thompson vs Walter Clark 1818. Joe Thompson a WNY blacksmith striker who through his attorney Francis Scott Key won a protracted battle for freedom for himself and his family in 1818.[47][48] Concerned about the growing problems associated with naval officers and senior civilians employing their slaves at naval installations, the Board of Navy Commissioners on 17 March 1817 issued a circular to all naval shipyards banning employment of all enslaved and free blacks. "Abuses having existed in some of the Navy yards by the introduction of improper Characters for improper purposes, The Board of Navy Commissioners have deemed it necessary to direct that no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard in the United States, & in no case without the authority from the Board of Navy Commissioners."[49] The same day Board President Commodore, John Rodgers sent a letter to Commodore Thomas Tingey reminding him only white employees were to be employed to replace the now banished black employees. "All Slaves & Blacks are to be discharged from the Navy Yard & none are to be employed in future, except under extraordinary Circumstances - & even then, they are not to be so employed except by the authority of the Navy Commissioners. Efficient white mechanics & Laborers are to employed to supply the places of those discharged under this order."[50] Characteristically such orders restricting black employment were followed by a period of waivers and exceptions as officers, senior civilian employees and slaveholders lobbied and pressed the Secretary and the Board to make accommodation for slave labor.

Commodore Isaac Hull upon assuming command of the Washington Navy Yard in 1829, found enslaved labor still entrenched. Hull a native of Connecticut, discovered that whites in this southern society would not perform so called "menial tasks" and that officers "servants" were black and consequently he purchased an enslaved man John Ambler,who was subsequently placed on the navy yard payroll. When Hull was later informed that by regulation slaves belonging to naval officers of the yard were not to be employed except as servants. Hull responded "I fear we could not find a set of men white or black, or even slaves belonging to the poor people outside the yard to do the work now done in the anchor shop... I have considered them the hardest-working men in the yard."[51] Yet in 1830, only three of the sixteen black workers listed on the payroll by Isaac Hull were counted as free. The rest of the African American workers were enslaved, mostly by none other than the officers and high-ranking civilians of the Yard itself.[52]

The 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike revealed the long simmering racial tensions on shipyard. "Competition for jobs on the navy yard was constant...white workers feared that competition from enslaved and even free blacks dragged down the wage scale."[53][54] The strike which rapidly morphed into the Snow Riot showed racism and slavery had seriously weakened the already tenuous nature of the workers bargaining situation. As day labor the striking workers found in a protracted dispute, absent effective organization and financial resources they inevitably suffered. Most of all their strike and subsequent riot revealed the corrosive effects of racism on the workforce as white workers sought to blame their own precarious economic situation on free and enslaved African Americans. Further, the strike left as part of its legacy a deep and abiding racial mistrust, which would linger. For next century, the history of the Washington Navy Yard strike of 1835 and Snow race riot remained an embarrassment to be glossed over and disassociated from the District of Columbia and Washington Navy Yard's official histories.

The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years, though free and some enslaved African Americans remained a vital presence.[55] There is documentation for enslaved labor euphemistically called "servants" still working in the blacksmith shop as late as August 1861.[56] One distinct difference between the Washington Navy Yard and other military installations was that many of the slaveholders were senior naval officers and civilians employed at the yard. While the majority of blacks at the navy yard were enslaved; a few free blacks, especially in the early years, received journeymen-level wages.[57]

Norfolk Navy Yard

editThe federal government purchased the Norfolk Navy Yard from Virginia in 1801. The new federal shipyard was, in reality, the successor to the former State of Virginia Naval Yard, where enslaved labor was a common place, and these practices continued until the Civil War.[58] Norfolk Navy Yard employed many slaves and these enslaved laborers provided their owners with a steady income.[59] On occasion slaveholders dropped all subterfuge as they blatantly placed their enslaved workers on the federal payroll. A glaring example, is found in 1830 when Navy Yard Commandant, Commodore James Barron, placed two enslaved women Lucy Henley and Rachel Barron on the shipyard payroll, as "ordinary seamen" and signed for their wages, see thumbnail.[60] Some idea of the human scale can be found in this exert from a 12 October 1831 letter of Commodore Lewis Warrington to the Board of Navy Commissioners in response to various petitions by white workers.[61] His letter attempts both to reassure the Board, in light of the recent slave rebellion led by Nat Turner, which occurred on 22 August 1831, and to serve as a reply to the dry dock's stonemasons who had quit their positions and accused the project chief engineer, Loammi Baldwin, of the unfair hiring of enslaved labor in their stead.

There are about two hundred and forty six blacks employed in the Yard and Dock altogether; of whom one hundred and thirty six are in the former and one hundred ten in the latter – We shall in the Course of this day or tomorrow discharge twenty which will leave but one hundred and twenty six on our roll – The evil of employing blacks, if it be one, is in a fair and rapid course of diminution, as our whole number, after the timber, now in the water is stowed, will not exceed sixty; and those employed at the Dock will be discharged from time to time, as their services can be dispensed with – when it is finished, there will be no, occasion for the employment of any.[62]

On 30 March 1839 Secretary of the Navy James K. Paulding, directed the Commandant of Norfolk Navy Yard, Lewis Warrington, to discharge all enslaved workers who belonged to "officers of the Navy, Marines & to persons holding appointments or employment under the Department of the Navy."[63] "What Secretary Paulding and his successors found to their dismay; was that this lucrative practice had become a feature of the Southern economy and had the tacit if not the willing participation many officers and senior civilians."[64] Just how pervasive and reliant on enslaved labor the shipyards had become, can be seen in Commodore Warrington's response of 21 June 1839, "I beg leave to state, that no Slave employed in this Yard, is owned by a commissioned officer, but that many are owed by the Master Mechanicks & workmen of the Yard -" He then went on explain,

"no Slave is allowed to perform any mechanical work in the Yard, all such being necessarily reserved for the whites; this keeping up the proper distinction between the white men & slave - If slaves are to be discharged for want of work, the discharge takes place from the lowest part of the roll, to the requisite number , by which favoritism is avoided- If work is to be suspended temporarily, as is sometime the case, for want of materials &c those who work with the mechanicks so situated are suspended – If Slaves are to be taken in, application to me is at all times indispensable & regular examination insures, as to strength, etc."

This same correspondence, contained a petition, signed by 39 master mechanics and journeymen slaveholders, endorsed by Warrington, that, 'Having hired these labourers for the year, they are [now] bound by the usual obligation to pay for them – If they are discharged , the only resort would be to hire them to persons out of the Yard & not in the employ of the government, at a great loss; had the individuals thus hiring them, will in all probability, reenter them & enjoy a profit for their services, increased by the loss which the undersigned must necessarily sustain – It is proper here to add that a number of the labourers of this description in the Yard, are owned by the Mechanics here who entered them, and the difficulty of hiring them out, if discharged, at this advanced period of the year is obvious."[66][67]

George Teamoh who as an enslaved man worked on the famous Norfolk Navy Yard, Dry Dock number 1, wrote" I was for sometime water bearer in the above Dock while it was in building. Helped dock the first ship that berthed there [USS Delaware], I have worked in every Department in the Navy Yard as a laborer, and this during very many long years of unrequited toil, and the same might be said of vast numbers, reaching to thousands of slaves who were worked, lashed and bruised by the United States Government..."[68] Teamoh recalled while at Norfolk Navy Yard in the 1840s the danger for any enslaved worker speaking to whites, "Slavery was so interwoven at that time in the very ligaments of the government that to assail it from any quarter was not only a herculean task, but one requiring great consideration, caution and comprehensiveness."[69]

A decade later despite the alienated voices of white mechanics complaining about the employment of blacks, the Norfolk Navy Yard continued to hire large numbers of bondsmen; by 1848 almost one third of the 300 of the workers at Norfolk Navy Yard were hired slaves. Many of these men worked as laborers and artisans".[70][71] U.S. Navy Yard Gosport daily station log entries for the year 1850, reflect, blacks solely utilized as laborers, in work groups, under white overseers.[72]

Norfolk Naval Hospital

editThrough the early nineteenth century, the Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Hospital extensively utilized enslaved labor. Enslaved blacks worked at the hospital as attendants, nurses, cooks and washers(laundresses)and gravediggers.[73][74]“References to slaves in the hospital case files and letters are frequent and signaled by the exclusive use of the familiar or occupational names such as "Capt. Warrington's (Serv.) Henry," "Commodore Barron's servant "Fanny the washerwoman", "washerwoman Isabella", "the washerwoman" or just the "washerwoman's child." Enslaved women and children were housed "fixed in an outbuilding" on the hospital grounds see Commodore Lewis Warrington letter (thumbnail) of 5 January 1832. Occasionally the status of these men and women is made explicit as in the Norfolk (Gosport) Naval Hospital Case file of 4 September 1825, where an enslaved washerwoman Fanny Ballott (see thumbnail) is "discharged from the Hospital and send to her owner."

Pensacola Navy Yard

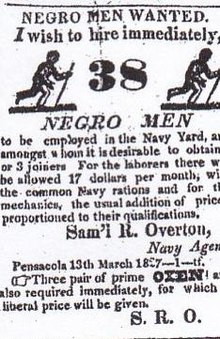

editPensacola Navy Yard was established in April 1826 because of its excellent harbor, the large timber reserves nearby for shipbuilding and its location which gave it proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean where the West India Squadron maintained a vigil to eradicate piracy and suppress the international slave trade. Ironically though this early navy yard was largely built and maintained by enslaved labor.[75] The Pensacola Navy Yard, the seventh federal shipyard, was built on the southern tip of Escambia County, Florida where the air station is today. Navy Captains William Bainbridge, Lewis Warrington, and James Biddle selected the site on Pensacola Bay. Pensacola lacked the manpower the navy needed to lay bricks, bend iron and haul lumber, therefore the government hired hundreds of bonds-people who they leased from local slave owners.[76] Even at an early date, the monthly "List of Mechanics, Laborers &C employed in the Navy Yard Pensacola" compiled by at the direction of the Navy Board of Commissioners and submitted in May 1829 shows over a third of the workforce was composed of enslaved labor. The list which reflects the names, occupations and wage rates of eighty-seven workers, enumerates thirty-seven slaves. This surviving early list is rare since it specifically notes the 37 laborers as "slave laborers".[77] Here as at other naval shipyards, civilian employees such as Navy Agent George Willis leased their slaves to the navy.[78]

To accommodate local slaveholders Pensacola Navy Yard hospital provided emergency medical care to enslaved laborers.[79] In 1838, Dr. Solomon Sharp USN, a slaveholder himself, took the unusual step of raising his objections to the free medical treatment provided enslaved navy yard workers and appealed directly to the Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson. Dickerson replied on 2 June 1838 "it is not deemed expedient to change the practice which prevails at the Navy Yard Pensacola..."[80] In addition to medical, the navy yard protected slaveholders from loss of their property, e.g.in 1838 navy yard endorsed three slaveholders claims for remuneration in the accidental death caused by drowning of enslaved employees[81]

Slavery remained integral to the Pensacola Navy Yard workforce throughout the antebellum period.[82] On 30 March 1839, Secretary of the Navy Paulding, specifically noted Pensacola has submitted to this Department from which it appears that slaves belonging to the officers of the Navy and Marine Corps and to other persons holding appointments or employment under this Department, are sometimes employed in the Navy - Yard of the United States."[83] As late as June 1855, the Pensacola Navy Yard payroll listed 155 enslaved employees.[84] Scholar Ernest Dibble concludes his study of the military presence in Pensacola with this coda "In Pensacola the military was not just the most important single force creating the local economy, but also the most important single influence to the spread of the slaveocracy in Pensacola."[85] Pensacola's location and comparative isolation, made escape for the enslaved extremely difficult and perilous. Historian Matthew J. Clavin noted that there is only one documented case of a fugitive slave, a twenty-one-year-old Pensacola Navy Yard blacksmith name Adam actually making a successful escape from antebellum Pensacola to the northern United States or Canada (see thumbnail).[86][87]

Fort Zachary Taylor

editThe U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of Fort Zachary Taylor in June 1845. The majority of artisans and mechanics were immigrant Irish and Germans recruited by the New York agency fresh upon their arrival from Europe. The backbreaking labor, however, was furnished by Key West slaves hired out under contract by their masters. Angela Mallory, whose husband Stephen Mallory was later the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, was among the local citizens who found such an arrangement profitable.[88] Slave hiring at Fort Taylor was typically part-time with approximately two-thirds of the 414 slaves working there for twelve months or less.[89] A recent study of slave hiring by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers concluded slave hiring for the period 1845–1860, was strengthened, "and all of this came about because of the involvement and support of the federal government and its agents the engineers."[90]

Fort Jefferson

editConstruction of Fort Jefferson, named after President Thomas Jefferson, was begun on Garden Key in December 1846. The Army employed civilian carpenters, masons, general laborers, and Key West slaves to help construct the fort. By August 1855, 233 white contract laborers were employed, but the slaves "were the backbone of the labor gang" according to Albert Manucy.[91] The labor force during the early years was made up predominantly of slaves from Key West. The Fort Jefferson slave rolls from October 1860 to June 1861 enumerate 16-36 slaves working as laborers, masons and cooks at a total cost of $4,877.00.[92] Although construction of the fort continued for 30 years it was never completed, largely due to changes in weapon technology, which rendered it obsolete by 1862.[93]

Federal policies and enslaved labor

editMilitary policies regarding enslaved labor were haphazard, more a mix of differing plans and ideas than a coherent program. Typically these policies followed those first utilized in 1792, by the District of Columbia Board of Commissioners, for the construction of the U.S. Capitol and the White House. In most all cases the federal government did not purchase slaves but instead leased or rented enslaved labor from private individuals in local communities surrounding forts and naval shipyards. Most of these agreements between military officials and slaveholders, which " propelled the slave system" were verbal, so called "gentleman's agreements".[94] Those committed to writing are rare and with the exception of the wages due the slaveholder are often short and vague, although some specified a period of time. These agreements were the chief means to obscure slave rentals and avoid public scrutiny.[95]

One example from the Department of the Navy is an 1824 note to Commodore Thomas Tingey that confirms a local slaveholder, sending his bondsman to the Washington Navy Yard, directly, to ask master blacksmith Benjamin King for work. "Sir, John B. Forrest having sent his black man Jos Smoot [See 1808 list of slaves for Joe Smoot] to my department for employment, I beg leave to observe that the work which I now have on hand does require more helpers, and I hope it will meet your approbation for him to be employed."[96] John B. Forrest was related to Thomas Tingey's second wife Ann Bladen Dulany.

There are two surviving agreements for enslaved labor both from the Army Corps of Engineers, dated 12 May 1829 and 25 March 1830. The 1830 agreement between the Corps and a local slaveholder is for his force of slave mechanics and laborers to be used in masonry and excavation. The agreement states, "Memorandum of a verbal agreement made between Capt. Wm. H. Chase on the part the Engineer department and Jasper Strong, surviving partner of Underhill and Strong in which Jasper agreed to perform or cause to be performed all the Brick Masonry that may be required in the construction of the Fortification at St. Rosa Island under the appropriation for 1830."[97]

To allay slaveholders fears of injury to their "property" in 1813 the Secretary of the Navy made a significant concession to those with slaves at the Washington Navy Yard. This was to include enslaved workers in the emergency medical care provided at the Washington Naval Hospital and later extended to other naval hospitals. "It is however to be understood that if any Master or Laboring Mechanics or common laborers employed in the Navy Yard shall receive any sudden wound or injury, while so employed in the Navy Yard, he shall be entitled to temporary relief. But if the person sustaining such injury be a Slave, his master shall allow out of his wages a reasonable compensation for such medical and hospital and as he may receive and if the injury of disability shall be likely to continue, the master shall cause such Slave to be removed from the public hospital Stores."[98][99] Here the shipyard followed precedent established by the District of Columbia, Board of Commissioners, when in 1792, they provided medical aide to enslaved laborers at work on the Capitol.[100] Naval hospitals treated a wide variety of maladies. Records from the Washington Navy Yard reflect that enslaved workers were treated for injuries and illnesses such as rheumatism, colic, cynanche, peritonitis, various venereal diseases, and fever. While race is rarely specified, both white and black patients were apparently housed in the same facility. Known enslaved workers such as diarist Michael Shiner and Commodore Thomas Tingey's two enslaved "servant[s]" Henry Carroll and Charles Lancaster were enumerated as patients at the naval hospital for parts of 1814, 1815 and 1829 respectively.[101] Navy later extended this important concession to slaveholders in Norfolk and Pensacola shipyards.[102] Three, the military never owned bondsmen but instead rented or leased slaves for use on forts and shipyards from local slaveholders. The military therefore enjoyed all the benefits of slave rentals with few disadvantages. Absent any formal contract military officers or senior civilian employees provided on site control discipline and direction. Slaveholders in contrast remained responsible should the slave suffer serious injury or death and in the event of a slave running away, were left to track the runaway or absorb the loss. Lastly the use of this system provided the military with an efficient, mobile and competent labor.[103]

Modern historians have examined the larger questions of whether slavery was economically viable and did slavery lower the wages of free workers, with differing results.[104][105][106][107][108] During the antebellum period, the economic argument for slave labor on federal shipyards and military installations, enjoyed de facto and occasionally open support. At the Washington Navy Yard slaveholder and master blacksmith, Benjamin King writing in 1809 to Commodore Thomas Tingey made the case for enslaved labor explicit "Experience has pointed out the utility of employing for Strikers Black Men in preference to white & of them Slaves before Freemen – The Strict distinction necessary to be kept up in the shop is more easily enforced – The liberty the men take of going & coming is avoided the Master of slaves for their own interests keep them to work. The Habits of Labor they are Inured to & their ability to stay at it are strikingly Obvious – It also takes some time to learn their Business & the time a White Man learns, he quits & the trouble is to be renewed."[109] In 1817, master plumber John Davis of Abel, bluntly made the case for the employment of enslaved× labor: "we found by long experience that Blacks have made the best Strikers in the execution of heavy work & are easily subjected to the Discipline of the Shop - & less able to leave us on any change of wages."[110] While rarely stated so bluntly the economics of slave hire at United States military installations were important to Army Corps of Engineers and the Board of Navy Commissioners. This support though was challenged by white mechanics who frequently expressed fear of economic competition from enslaved labor and by those abolitionists who saw slavery as a moral abomination. Most critics of enslaved hire on federal installations cited economic reasons. One writer condemned the BNC as "Unfeeling men! You have reduced the wages of this yard. What an abominable act of tyranny!"[111] A local annalist, writing in 1825, expressed the same concern, "There is a general disposition to reduce the pay of laborers to a small pittance, and to introduction and employment of non – resident slaves a policy which is injurious to the interest of the city."[112]

After examining federal shipyard wages, historian Linda Maloney, noted white worker fears while certainly misdirected had some rational economic basis that is the so-called "cooling" effects of enslaved labor on free wages had a harsh reality. Maloney found laborers at the mostly all-white, Massachusetts, Charlestown Naval Yard received wages of $1.00 a day and sometimes more, while those at the Washington Navy Yard, both white and black, earned but $0.72.[113] On 21 November 1846, the Commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard, Charles W. Skinner responded to the Secretary of the Navy John Mason, that wages at Baltimore were $1.75 per for a skilled carpenter while at Norfolk they were $1.50 which he attributed to very few tradesmen in the area and "the work being generally performed by Negros."[114] and We are fortunate to possess some specific wage data. Responding to a BNC request, in 1821, Commodore Thomas Tingey supplied data on scale of wages for various shipyard occupations from 1801–1820. Tingey's submission has one serious omission, no data for slaves. While most of the data covers the decade 1810–1820, there is sufficient evidence to reveal a significant drop in workers income. For example, in 1801, a painter's per diem wage was set at $1.56; in 1820 a painter's daily wages were but $1.52–1.32. Far worst were the wage rates for ship caulkers. Tingey reported they were paid $1.81 in 1810, but, their wages declined to $1.44 by 1820. Shipyard laborers, who occupied the lowest rung in the hierarchy, were paid $0.85–0.75 in 1810, a decade later saw their wages declining to $0.80–0.68 in 1820. Ship caulkers and laborers, two occupations with large numbers of blacks, saw considerable decline.[115] As these figures represent wages paid to free labor we may surmise the wages for enslaved labor was substantially lower.

Similarly historian Robert Starobin 's study of the Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard reflects "The labor rolls of the Gosport Navy Yard reveal that in the 1830s slaves produced as much as white workers for two thirds the cost..." He reports that blacksmith strikers pay during this period ranged from 72 to 83 cents per day, averaging close to 72 cents. Whereas the daily wages of white workers ranged from $1.68 to $1.73, he found that even adding a hypothetical 30 cent per day for the enslaved workers maintenance, still left a large wage disparity.[116]

However competition from slaves was not the determinant factor in the flatness of wages in Washington or Norfolk; wages were low because there was a surplus of low-end white workers and those workers had little political leverage in the District or elsewhere because craft workers saw them as competitors rather than allies, and thus excluded them from their organizations.[117] While enslaved labor declined after the 1835 strike at the Washington Navy Yard; in Florida and Virginia the use of slave labor became the norm because it was profitable to both the government and the slave owners.[118][119][120]

Public outcry and petitions

editIn the late 1820s public complaints and petitions to end enslaved labor on federal installations increased dramatically. This was reflected in the growth of movements like the American Colonization Society and abolitionism. During this same period, broadsides condemning the sale and keeping of slaves in the District of Columbia begin to proliferate. At the same time, the campaign for the Congress to abolish slavery in the nations capital became widespread. Abolitionists' attempts to galvanize public opinion began with the promotion of narratives of enslavement and freedom by former slaves. One of the earliest, by Charles Ball, a former enslaved shipyard worker at the Washington Navy Yard, who fought with Commodore Barney's flotilla during the war of 1812, authored A Narrative of the life and adventures of Charles Ball, a Blackman, published in 1837.[121] Ball's story is one of the earliest and served as model for many others to follow.

The proliferation of enslaved labor quickly aroused the fear of white mechanics and laborers. At the Washington Navy Yard and Norfolk Navy Yard mechanic's bitterly resented any hint of the admission of blacks as apprentices in the skilled trades. Periodically, too public anger with naval officers and civilians renting their bondsmen to the Department came to the fore. One critic specifically complained, "Another officer hires a negro for 60 dollars per annum; and lets him to superior officer for one dollar per diem. A fine speculation; but public losses are private benefits." One District resident stated that the employ of slaves at the shipyard and other public installations prevents white men from accepting work amongst them as the "whites feel it to be a degradation"[122] White foremen and workers expected all blacks to be deferential, but over the time black workers began to speak out and to question the equity and fairness of their pay. In 1812, a petition to the Secretary of the Navy, from a group of white blacksmiths, stated their resentment of blacks they perceived as "insolent". They wrote:

Your petitioners further complain that they [ar] e now subjected to the insolence of negroes employed in the Navy Yard, altho' no redress is [suffic]iently provided for your petitioners, against the misconduct of blacks. That one of their body was lately threatened with being discharged for having struck a negro who had grossly misbehaved & they conceived that some provision ought to be made for the purpose of restraining the misconduct of blacks & of only employing such as are orderly & absolutely necessary.[123]

Fear of black employment pervaded all federal shipyards. In 1843, the Richmond Whig protested "the employment of slaves to the exclusion of white labor in the Norfolk Navy Yard,...the truth is, that slave labor ought never to be employed by the government at all except as a make shift - when white men cannot be obtained."[124] This is equally true of shipyards in the north. As late as 1862 Admiral Hiram Paulding responding to a rumor of the employment of free blacks, publicly confirmed in the New York Times, that to his knowledge no African American was ever employed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.[125] The majority of white mechanics and laborers saw free blacks as a direct threat to their livelihood and agitated for their exclusion from all skilled trades and supervisory positions. The notable exceptions took place at WNY in the first decades of the nineteen century, when slaveholders sought unsuccessfully to enter their slaves in skilled crafts such as shipwright, or carpenter. In each instance, these efforts were bitterly contested. For example, in March 1811 a committee of shipwrights wrote the command on behalf of themselves and the others trades. In their letter they remonstrated "against the practice of master workmen admitting black or colored slaves, as apprentices to the master workmen & those allowed the privilege of apprentices." They stressed they considered, "such practices as degrading to their profession, inasmuch as parents who may have children to put out will think it disreputable to bind free children in contract with Negro slaves."[126][127]

The BNC main concern appears to have been the number of officers and master mechanics who rented their slaves to the Navy. The Board of Navy Commissioners occasionally took drastic steps to limit the number blacks and on 17 March 1817, they issued a circular to all naval shipyards, banning employment of all blacks and seemingly questioning the activities of some whites.[128]

Abuses having existed in some of the Navy yards by the introduction of improper Characters for improper purposes, The Board of Navy Commissioners have deemed it necessary to direct that no Slaves or Negroes, except under extraordinary Circumstances, shall be employed in any navy yard in the United States, & in no case without the authority from the Board of Navy Commissioners.

The same day BNC President Commodore, John Rodgers sent a letter to Thomas Tingey reminding him only white employees were to be employed to replace the now banished black employees. "All Slaves & Blacks are to be discharged from the Navy Yard & none are to be employed in future, except under extraordinary Circumstances - & even then, they are not to be so employed except by the authority of the Navy Commissioners. Efficient white mechanics & Laborers are to employed to supply the places of those discharged under this order."[129] On 3 April 1817 a similar reminder was sent to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard directing the "employment of none but white men in the Yard, if they could be procured, if not he was directed to apprise the Board that means might be taken to send the requisite workmen".[130] Characteristically such orders restricting black employment were followed quickly by a period of waivers and exceptions as officers, senior civilian employees and slaveholders lobbied and pressed the Secretary and the Board to make accommodation for slave labor.[131]

"Gentleman's agreements"

editIn 1809, the United States Congress passed a law requiring bidding for contractual services and that the Government publicly announced what it wished to buy, and everyone was given an opportunity to bid on the work. Verbal contracts or "gentleman's agreements" were one means of getting around this barrier.[132]

The BNC directive was in part an attempt to adhere to this statute and to end the practices that naval officers and shipyard master mechanics used to employ enslaved labor. One of the most egregious methods was to place enslaved workers as seamen on the shipyard employment rolls of "the ordinary". The ordinary is where naval ships being refitted or taken out service were held in reserve. African Americans Charles Ball and Michael Shiner were some the many enslaved workers navy yard enumerated on the military muster as O.S. or Ordinary Seamen.[133]

On occasion and most likely inadvertently, this practice is unequivocal in official documents. This example was found in the Washington Navy Yard station-log for 29 June 1827. A lieutenant John Kelly was anxious to have his slave, Thomas Penn enrolled in the ordinary of the Washington Navy Yard so that he could draw his wages. "Sir, The term for which my man (Thos Penn) was shipped in the Navy in Ordinary, having nearly expired and being informed that you are about to enter men again in that service, may I solicit the favor of you to have Thos Penn entered again and oblige your Obt Servt."[134] Lt. Kelly was successful for Thomas Penn is again enumerated as "O.S." Ordinary Seaman, number 40 in the 1 January 1829 muster of the WNY ordinary, see thumbnail image.

This particular subterfuge was wide spread, see Washington Navy Yard 1826 muster thumbnail. Similarly at Norfolk Navy Yard, former slave George Teamoh wrote, "I was again hired by the U.S. Government to work in its ordinary service. - was there some two years [1843-1844] on board Ship USS Constitution lying in ordinary off Norfolk Navy Yard..."[135] Teamoh was even issued a discharge dated 10 September 1845, certifying that George Teamoh Ordinary Seaman was "regularly discharged from the United States Ship Constitution in Ordinary at Navy Yard Norfolk, and from the sea service of the United States." Teamoh was not fooled, "that branch of the U.S service, so far as hirelings were concerned, was but little different from letting out to a building contractor, varying only in point of punishment - whipping post and cow hide - gang-way and cat-o.nine tails. Lawfully these now constitute no part of American institutions."[136] Enslaved workers at Norfolk Navy Yard were frequently designated as "Landsmen" and "Ordinary Seamen" on the payrolls of "the Ordinary". On 6 December 1845, Commodore Jesse Wilkinson confirmed Teamoh's assertions that this was a long-standing practice at the Norfolk Navy Yard to the Secretary of the Navy. Wilkinson wrote "that a majority of them [blacks] are negro slaves, and that a large portion of those employed in the Ordinary for many years, have been of that description, but by what authority I am unable to say as nothing can be found in the records of my office on the subject – These men have been examined by the Surgeon of the Yard and regularly Shipped [enlisted] for twelve months"[137][138][139] In yet another instance of apparent subterfuge, two enslaved females (see thumbnail), were both listed on the 1830 muster rolls of the naval shipyard as OS 2c or Ordinary Seamen 2nd class and their wages signed for by Commodore James Barron.

Discipline and control

editPunishment for slaves on federal military installations, varied widely and was never systematic. Legally enslaved workers, remained the property of the slaveholders; who normally administered discipline themselves. However, on a day-to-day basis, the surviving records reflect, when hired to the military, slaveholders generally delegated military officers and senior civilians wide discretion. Punishments ran the gamut from verbal reprimands, threats to inform the slaveholder of an infraction, hits with a boatswains starter (a piece of rope, dipped in tar), whippings administered with a cat of nine tails this was a multi tailed whip, the "Cat" was made up of nine knotted thongs of cotton cord, about 2½ feet or 76 cm long), designed to lacerate the skin and cause intense pain, and lastly, removal from the Yard rolls.[140] The evidence for such actions against slaves is rarely reported officially, the following examples are from the Washington Navy Yard

In 1810, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, engineer and architect, wrote in a letter to a friend:

"Ben. King [WNY master blacksmith], is forging the Crank. He has thought proper to alter his opinion and is making it the most tremendous lump of Iron, the Necks 4 inches in diameter, the squares 5 inches. He now thinks it too weak. He has been swearing and whipping his black Strikers at a terrible rate these two days past ..."[141] Latrobe had come to hold King in low regard but there is no reason to think he is speaking metaphorically. Michael Shiner writing a few years later recounted how similar infractions were handled. Speaking back to an officer, overstaying leave, fighting, or getting drunk could result in "a starting" that is being hit with the boatswains starter; for more serious offenses, blacks were whipped with the cat of nine tails. Shiner recollected, Tingey's footman taken to the Rigging Loft for punishment. "At the same time [spelling as per original] they wher a lad comerder tinsay foot man had been cuting some of his shines at the house on the 4 and they taking him down to the rigin loft that it give him a starting and they wher going to give me starting two. In January 1827, he wrote of John Thompson's, alleged disrespect to Sailing Master, Edward Barry, for this offense he was taken to the Rigging Loft for punishment, "We all hands of the ordernary men Wher cauledup in to the rigin loft to giv an acount of our selves captin Booth Wher present in the loft first lieutenant thomas crab and Sailing master edwar Barry who had prefered the charge against thomas pen captin Booth sais now thomas pen you are brought befor me for using abusive and insultin language to an officer of this yard what have you got to say for your selve captin thee had kein a ben drinkin and if the said anything to Mr Barry out of the Way they are sorry for it and if thou pleases and if Mr Barry pleases to excuse the will never do so no more sire dont you no the danger of givin insolence to an officer Well tell the captin if thou please excuse me this time never do so no more sire Mr Barry reply i will excuse him this time captin now Thomas pen i will let you oft as Mr Barry has excuse you Now captin and Mr Barry the[y] is ten thousand times oblige to thou for letin [him] off captin Booth and first lieutenant crab sail Master edward Barry Boatswain David eaton turned their backs and laught and told Tom to go on now and behave your selves and never struck him a crack When pen got up to the ordernary house among the men are sais Tom pen by the powers of Mol kely didnt the(y) tell thou if ever thou let the[e] get into quaker sistom that thou would never Wip the[e] so Tom pen got clear of the cats [cat of nine tails] that day by talkin quaker to captin Booth and the rest of the officers."[142]

For the enslaved workers punishment might occur irregularly, and whippings infrequently, but such brutal actions need not have been numerous to inspire fear. Michael Shiner relates how enslaved "ordinary seaman" John Thompson anticipating a whipping, managed to mollify the anger of the Sailing Master Barry, by "talkin quaker", that is, being publicly humble and deferential to his accuser. Shiner himself was punished for returning late and being drunk, by being placed in double irons, hand and foot, and then placed in the guard house for twenty four hours.[143]

At Norfolk Navy Yard George Teamoh describes, that whipping and even a murder were part of the regime, "He writes [2nd Engineer Thomas Symington] stated I had "ruined the U.S. Government property and the Dry-Dock in particular, and that no one could or ought to live who had been so neglectful of their duty..." "I knew full well too, that he had on several occasions, previously whipped me unmercifully for the merest fault, such as being late at work not making steam within the same time out of wet sappy wood as of dry heart &c.&c."[144] For the enslaved Teamoh recalled, the navy yard "was but little different from letting out to a building contractor, varying only in point of punishment - whipping post and cow hide - gang-way and cat-o.nine tails."[145]

Despite such hardship Charles Ball, Michael Shiner and thousands of other slaves, working on federal military installations and shipyards, knew, there were worst horrors. The enslaved were aware any disgruntled slaveholder could simply "sell them South", which meant the breakup of their families, their friendships and their hopes to a life of brutal plantation labor.[146] Teamoh recalling his years at Norfolk Navy Yard, confirms, " I was, occasionally at work in the Navy Yard, and with the hundreds of others in my condition felt to remain there rather than being worst situated, or sold."[147]

Over time the Navy Department became increasingly concerned with security, and keeping track of enslaved "servants" became a regular function of the Washington Navy Yard guard force. During the antebellum era "servant" was the favorite euphemism for enslaved labor in official correspondence. The continuing use of blacks, free and enslaved as drivers of private carriages and as servants in officers' quarters remained a subject of official concern into the 1850s. The following extract from navy yard regulations, provide some idea of this surveillance: "Officers Servants are to be passed in and out by the Watchman at the Flagstaff; and each Servant is to be furnished (and none passed out without it) with a permit by his Master, or a pass, which in going out he is to leave with the Watchmen Aforesaid, to be returned by him next morning, or by his relief to the Officer whose name is on it. -- The Servant is not to take it with him out of the yard-- neither is it to be given back to him when he returns-- it is to be kept by the Watchman. The passes to be written on a piece of paper, & that pasted to a small board, which the Watchman can hang up in his box."[148]

At the Washington Navy Yard, the daily station logs reveal watch officers were on occasion directed, to keep an eye out on a particular slave's movements. For example, from an entry on 18 May 1828 "This day fresh breezes from the N.W. and fair weather Teppit has not made his appearance." This entry is most likely for Thomas Teppit. Teppit an enslaved man had been placed on the muster rolls as Ordinary Seaman from September 19, 1827. Most likely Teppit overstayed his pass or ran for freedom. There are two comparable entries for diarist Michael Shiner. For Saturday, 27 December 1828, the officer of the watch recorded, "Michl Shiner who had liberty out from Wednesday in till Friday morning has not came in yet." On Sunday, 28 December 1828: Shiner returned, "This day pleasant airs from the SW and fair weather. Michael Shiner got home this evening." How pervasive this type of day to day scrutiny was, is difficult to ascertain; Shiner and Teppit are the only other names mentioned in surviving logs but the regulations quoted suggest that the actual monitoring of the activities of "servants" became a fixture of gate guard duty.[149][150]

Resistance and end of slavery

editOn 23 January 1830, a petition, from white workmen in Gosport (Norfolk) Navy Yard complained to the Navy Department of the shipyard use of slaves as stonemasons. "On application severally by us for employment we were refused, in consequence of the subordinate officers hiring negros by the year..." Comparable petitions continued throughout the antebellum era. In 1839, William Mc Nally, an ex-Navy gunner, published his expose of the naval and merchant service. Among his charges, were that naval officer countenanced and profited from slaves employed on naval vessels and in the navy yards as laborers "to the exclusion of white people and free persons of color."[151]

Another writer noted that the employment of slaves at the naval yards had become a source of great complaint, "but it is of no use; corruption in this government, at the present moment, is the order of the day."[152] In response to such criticism beginning in 1839, the active naval service began to take steps to limit the number of black seamen to five percent and stressed that under no circumstances were slaves to be entered. Stung by many critiques the federal government, with reluctance, dissociated itself from the practice of employing slaves on public projects. Congressional oversight grew and in 1842, the Congress, "compelled government agencies to report the number of slaves they were hiring".[153] The Secretary of the Navy, Abel P. Upshur, in reply to a question from the Speaker of the House of Representatives, stated; "There are no slaves in the Navy, except only a few cases in which officers have been permitted to take their personal servants instead of employing them from crews.[154] There is a regulation of the Department against employment of slaves in the general service. Upshur went on to carefully note, "neither regulations nor usage excludes them as mechanics, laborers, or servants in any branches of the service where such a force is required."[155] One scholar reviewing Secretary Upshur's 1842 statement with the employment records of the Pensacola Navy Yard for the same period, stated, "For whatever reason, Upshur provides Congress with patently false information about the navy's use of slave labor in his 1842 report."[156]

The decades of the 1820s through 1850s saw growing African American opposition to enslavement. The narratives of two former Washington D.C. residents Charles Ball and Thomas Smallwood provide vivid accounts of bondage and resistance in the nation's capital. Charles Ball, who, worked at the Washington Navy Yard for two years as a cook and after several escapes and recaptures made his way to freedom; in 1837, wrote his autobiography.[157] In his account, Ball wrote his life as an enslaved laborer was, "one long waste, barren desert, of cheerless, hopeless, lifeless slavery; to be varied only by the pangs of hunger, and the stings of the lash." Thomas Smallwood, author of the Narrative of Thomas Smallwood, Colored Man, Giving an Account of His Birth – The Period He was Held in Slavery – His Release - and Removal to Canada, Etc.: Together with An Account of the Underground Railroad, grew up in the District of Columbia, and worked at the navy yard in the 1840s.[158][159][160] During his years in the District of Columbia, Smallwood operated a small shoe repair business directly across from the navy yard gate.Though he was remembered with the impressive moniker "Smallwood of the Yard" surviving muster and payroll records do not show him, directly employed by the navy. [161]Secretly he served as an agent of the clandestine Underground Railroad, where he claimed to have led as many as 150 escapees to freedom.[162] In his narrative, Smallwood declared; "[slaveholders] should also remember that justice has two sides, or in other words, a black side as well as a white side, and if it is just for slaveholders to compel men and women to work for them without pay, because they are black, and they have the power to do so; then it is equally just for them, or their friends, to deprive their masters of such labor without pay." In 1848, two Washington Navy Yard blacksmiths Daniel Bell and Anthony Blow helped plan one of the largest and most daring mass slave escapes of the era.[163][164]

As historian Peter H. Wood stressed, "No single act of self – assertion was more significant among slaves or more disconcerting among [southern] whites than that of running away." Slaves were valuable property and slaveholders frequently went to great lengths to recover fugitives including offering rewards for capture and return.[165] Runaways with marketable talents such as blacksmiths and ship caulkers were valuable hence slaveholders were often desperate to reclaim their lucrative possessions. One such runaway was the daring and resourceful David 'Davy" Davis. Davis repeatedly attempted to escape enslavement, and even to wrest his freedom in court. As a blacksmith striker at the Washington Navy Yard, Davis worked six days a week, twelve hours a day. Davis with Jim, another blacksmith, sought freedom and escaped on 14 June 1809.[166] A reward notice ran on 16 June 1809 proclaiming a $100.00 (~$1,948 in 2023) reward for Davis and Jim. James Cassin labeled the two men "old runaways" implying they had made previous attempts to find freedom.

He also stated they "will try to pass for freeman" perhaps presenting forged freedom papers with the implication that one or both may have been literate. By 17 June 1809, Davis was captured and held in the District of Columbia Jail. Somehow Davis was able get an attorney to file a petition on his behalf in the District of Columbia Circuit stating that he was illegally held in bondage and that slaveholder James Cassin sought to remove him from the District and take him to lucrative slave market of New Orleans for sale.

"The humble Petition of Davy Davis, humbly sheweth, that your Petitioner is detained in slavery by James Cassin — and as he is born free he prays that process may be awarded to compel the appearance of the said James Cassin to answer his complaint." Davis suit was of no avail Cassin reclaimed him and again rented him to the navy yard.[167] The July 1811 WNY payroll reflects David Davis was again working at the navy yard, that month for 18 ¼ days @ 85 cents per day. The same document shows James Cassin slaveholder signed for and collected Davis monthly pay of $15.54.[168]

Davis was determined to escape enslavement and make a life for himself and in 1812, he made yet another flight to freedom, this time apparently successful.

Thirty Dollars Reward,

Ranaway from the Navy Yard on Monday the 26th of May, a Negro man the property of the subscriber, known by the name of DAVID DAVIS; he has been working for the last three years as a helper in the blacksmith's shop; he is about 25 years of age, and 5 feet 10 to 5 feet 11 inches height; some time ago he had his left arm broke a, and lost his fore finger. I will give $ 20 for the apprehending him if taken in the district, or 30 if out of it and lodging him in jail. He was bought of Ed. H. Calvert in Prince George's county, where he has some friends, and it is probable he will stay about there; he has been in Baltimore jail where I bought him out. All persons are forbid harboring him under a penalty.

J. Cassin

P.S. Should he voluntarily return to his master, he promises to forgive him.

Georgetown, June 2 –[169]

Cassin's appeal "Should he voluntarily return to his master he promises to forgive him" is a common plea in the reward notices of desperate masters hoping to cajole a runaway slave into voluntarily return.

While there is considerable evidence that public outcry and black resistance greatly diminished the use of enslaved labor on the Washington Navy Yard. This is not true of Norfolk and Pensacola navy yards where enslaved labor enjoyed greater support in the white community and caused less turmoil. Nor was this true of U.S. Army installations such as Fort Jefferson, Fort Zachary Taylor and others where Corps of Engineers continued to use slave labor almost until the Emancipation Proclamation.[170] Former Norfolk navy yard slave, George Teamoh, knew firsthand "slavery was so interwoven at that time in the very ligaments of government that to assail it from any quarter was not only a herculean task, but one requiring great consideration, caution and comprehensiveness."[171]

Despite Secretary Upshur protestations, there were still slaves in the Navy. In the summer of 1844 seven slaves from Pensacola Navy Yard aided by Jonathan Walker a sympathetic white shipwright made a daring, albeit failed effort to gain their freedom. The subsequent imprisonment and trial of Walker brought increased public attention and made national headlines.[172][173] The seven slaves were brutally beaten and returned to the slaveholders. Walker for his part spent months in jail and was later sentenced to be branded on his hand with the letters "S S" for slave stealer.[citation needed] In April 1848, Washington Navy Yard blacksmiths Daniel Bell and Anthony Blow helped plan one of the largest and most daring slave escapes of the era. Their plan involved seventy seven fugitives and a daring 225-mile voyage to freedom. This dramatic escape failed but the shear scope and audacity of the effort greatly alarmed slaveholders and the federal government.[174][175][176][177]

The Civil War though ultimately forced the end of slavery. In Washington D.C. while the majority of naval officers and a few white employees went south, including the last antebellum Commandant, Commodore Franklin Buchanan, black employees remained steadfast supporters of the Union cause and showed no equivocation. In 1861, Michael Shiner who had spent over a decade as a slave in the Washington Navy Yard; in his diary conveys the enthusiasm of an African American for the Union and the war "On the first Day of June 1861 on Saturday Justice Clark was sent Down to the Washington navy yard For to administer the oath of allegiance to the mechanics and the Laboring Class of working men Without Distinction of Color for them to Stand by the Stars and Stripes and defend for the union and Captain Dahlgren Present and I believe at that time I Michael Shiner was the first Colored man that had taken the oath in Washington DC and that oath Still Remains in my heart"[178][179]

In summary, the introduction of slave labor on navy yards and army installations grew out of local practices, mirroring those established in the surrounding communities and those first used by the new federal government in the construction of the United States Capitol and President's House after 1814, the White House. The simultaneous employment of white, free black and slave labor had long precedents reaching back into the colonial era at Norfolk. Slave rentals and leasing by the army and navy expanded slavery especially in Florida where the construction and maintenance of military installations "was the primary source for the expansion of slavery" and provided a ready market for slaveholders to rent their bondsmen.[180] Opposition to slave labor on military installations, was always sporadic, but gathered increased strength and momentum with each decade. Black resistance and white fear of an expanding population of free blacks led to calls for congressional oversight and a more accurate accounting of slaves on military installations.[181]

The District of Columbia Emancipation Act signed on 16 April 1862, ended slavery forever in the nation's capital. In his entry for that day, Michael Shiner, wrote a brief account of the Act concluding with the words: "Thanks Be to the Almighty."[182] The final death of slavery was signaled when on 1 January 1863; President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamtion into law; while the Civil War would continue for two more bloody years there was to be no turning back. Shiner copied the proclamation carefully into his diary and later, reflecting on his freedom, emphatically stated, "The only master I have now is the Constitution."[183]

References

edit- ^ Starobin, Robert S. Industrial Slavery in the Old South Oxford University Press: New York, 1975, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F. Slave Rentals to the Military: Pensacola and the Gulf Coast Civil War History Volume 23, Number 2, June 1977 pp. 101–113

- ^ Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791-1861 (University of Kansas:Lawrence Kansas 2011), p. 135.

- ^ Warden, D. B. A Chorographical and Statistical Description of the District of Columbia, the Seat of the Government of the United States. Paris: Smith and Co., 1816, pp. 46 and 64

- ^ Tomlins, Christopher, In the Matter of Nat Turner A Speculative History, (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2020) pp. 157-158

- ^ Wortley, Emmeline Stuart, Travels in the United States, etc., during 1849 and 1850 New York: Harper and Brothers, 1851, p. 85.

- ^ Gottlieb, M. S., & the Dictionary of Virginia Biography. George Teamoh (1818 – after 1887). (2015, November 30). In Encyclopedia Virginia http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Teamoh_George_1818-after_1887.

- ^ Teamoth, George God Made Man Man Made the Slave The Autobiography of George Teamoh editors F. N. Boney, Richard L. Hume and Rafia Zafar Mercer University Press: Macon 1990, p. 83

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 497–539, p. 499.

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 497–539.

- ^ Sharp, John G., African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 - 1865 Hannah Morgan Press: Concord, 2011, p. 6.,http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/wny2.html

- ^ Smith, Mark A. Engineering Slavery The U.S.Army Corps of Engineers and Slavery at Key West Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2008),497–539.

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 497–539

- ^ Clavin, Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers Harvard University Press:Cambridge 2015,

- ^ Hamdani, Yoav (2022). The Slaveholding Army: Enslaved Servitude in the United States Military, 1797-1861 (Thesis). Columbia University. doi:10.7916/7b3r-y514.

- ^ Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791-1861 University of Kansas: Lawrence Kansas 2011,136.

- ^ Adam Costanzo George Washington's Washington Visions for the National Capital in the Early Republic (University of Georgia Press: Athens Ga. 2018), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Thomas Johnson, David Stuart, and Daniel Carroll, Commissioners to Thomas Jefferson, 5 January 1793 Commissioners Letter book Vol. I, 1791--1793, NARA

- ^ Allen William C. History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 2005

- ^ Allen, William C. p.5

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob Use of Slaves to Build and Capitol and White House 1791-1801, chapter three, accessed Oct 31, 2017 http://bobarnebeck.com/slavespt4.html.

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob, Slave Labor in the Capital: Building Washington's Iconic Federal Landmarks, (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2014), p. 32.

- ^ Sharp, John G. African Americans, Enslaved & Free, at Washington Navy Yard http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/wny2.html

- ^ Smith, Mark A. Engineering Slavery The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Slavery at Key WestFlorida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2008), 497–539, pp. 514–515

- ^ Clavin, Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers Harvard University Press:Cambridge 2015.

- ^ Dibble, Ernest E. Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence Pensacola News Journal: Pensacola 1974, p. 62.

- ^ John G. Sharp Researchers and Family Historians Guide to Documents Reflecting African Americans in Slavery and Freedom in the District of Columbia 2010. Accessed 30 November 2017 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/slavery/slaveryintro.html

- ^ Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791-1861 (University of Kansas: Lawrence Kansas 2011), 256n132, 266n152.

- ^ John G.Sharp Washington Navy Yard an Introduction for Researchers 2010 accessed 29 November 2017 http://www.genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/wnyintro.html

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob. Use of Slaves to Build and Capitol and White House 1791-1801, chapter three, http://bobarnebeck.com/slavespt4.html, accessed 12 Nov 2017

- ^ John G. Sharp EARLY GOSPORT DOCUMENTS Gosport Navy Yard Employees, Occupation & Per Diem Pay Rates accessed 30 November 2017 http://usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp4.html

- ^ Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard Washington City, from 18 May 1815 to 1 November 1817 edited and transcribed by John G. Sharp 2011 accessed 4 Dec 2017 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/1815musterbook.html and Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard Washington City, 1 January to 31 December 1826 edited and transcribed by John G. Sharp 2011 accessed 4 Dec 2017, www.historicwashington.org/docs/WNY1826MusterreMichaelShiner.doc

- ^ Smith, Mark A. Engineering Slavery pp. 515–516

- ^ Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791 -1861(University of Kansas Press: Lawrence Kansas 2011), 136.

- ^ Wilkinson to Bancroft, 6 December 1845, letter 84, volume 325, 1 Nov 1845-31 Dec 1845, RG 260, M125 "Captains Letters" National Archives and Records, Washington D.C.

- ^ Arnebeck, Bob, Slave Labor in the Capitol Building Washington's Iconic Federal Landmarks, History Press: Charleston, 2014, Appendix. List of Masters and Their Slaves

- ^ John G. Sharp Washington Navy Yard 1808 Reduction in Force, Genealogytrails.com, 2008, accessed 18 Nov 2017 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/wny1808rif.html

- ^ John Cassin to Secretary of the Navy Smith 18 May 1808, RG45/M125 NARA.

- ^ John G. Sharp 1808 Muster of the Washington Navy Yard Prepared for Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith Genealogytrails, 2008 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/wny1808ordmuster.html

- ^ Pacheco, Josephine E. The Pearl, A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005, p. 20.

- ^ Nathaniel Haraden to Board of Navy Commissioners 11 May 1815 NARA RG45 E307 v. 1.

- ^ Daily National Intelligencer, 2 June 1812

- ^ Boston Patriot & Daily Chronicle 19 January 1820, p. 3.

- ^ Daily National Intelligencer 2 March 1825

- ^ "Introduction". NHHC. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Thomas III, William G., Kaci Nash, Laura Weakly, Karin Dalziel, and Jessica Dussault. O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed 22 Nov 2017 http://earlywashingtondc.org

- ^ Leepson, Marc What So Proudly We Hailed, Francis Scott key A Life Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2014, p.26.

- ^ Joe Thompson, Nelly Thompson, & Sarah Anne Thompson v. Walter Clarke Reports of Cases Civil and Criminal in the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, from 1801 to 1841 accessed 22 Nov 2017 http://earlywashingtondc.org/cases/oscys.case.0036.005

- ^ BNC Circular to Commandants of Naval Shipyards, 17 March 1817, RG 45, NARA

- ^ Commodore John Rodgers to Thomas Tingey 17 March 1817, RG45 NARA.

- ^ Maloney, Linda M.,The Captain from Connecticut: The Life and Naval Times of Isaac Hull. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986, p. 421.

- ^ "Riot Acts: "Rereading the Riot Acts"". www.riotacts.org. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Brown, Gordon S. The Captain Who Burned His Ships Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750-1829 Naval Institute Press: Annapolis 2011, p. 147.

- ^ John G. Sharp Washington Navy Yard Payroll April 1829 Genealogy Trails http://www.genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/wny1829aprlemployees.html

- ^ "Introduction". NHHC. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ "Navy-Yard, Washington, History by Hibben". NHHC. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ John G. Sharp 1808 Muster of the Washington Navy Yard Prepared for Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith Genealogytrails, 2008 http://genealogytrails.com/washdc/WNY/wny1808ordmuster.html

- ^ Christopher Tomlins, In the Matter of Nat Turner A Speculative History (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2020) 154

- ^ Collison, Gary, Shadrack Minkins from Fugitive Slave to Citizen (Harvard University Press: Cambridge 1997), 25

- ^ Miscellaneous Records of the Secretary of the Navy, "Muster Rolls" 1830, p. 40, roll number 0183, RG 45, NARA Washington D.C. "Rachel Barron" enumerated as # 2, O.S. 2nd, wage $ 15.55 (~$445.00 in 2023) and "Lucy Henley" # 4, O.S. 2nd wage $15.55. Both women wages signed by James Barron.

- ^ Sharp, John G., Gosport Navy Yard, letter of Lewis Warrington to the BNC 12 Oct 1831 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp.html#enslaved

- ^ Louis Warrington to Board of Navy Commissioners 12 October 1831 NARA RG45 transcribed Sharp, John G. accessed 28 February 2019 http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/nnysharp.html#enslaved

- ^ Circular Letter, 30 March 1839, to Navy Yards Washington, Gosport (Norfolk) and Pensacola, Navy Department, Miscellaneous Records of the Navy Department, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of Naval Records and Library, 1803-1859, RG 45, Roll 0459, pp. 84-85

- ^ Sharp, John G. African Americans, Enslaved & Free, at Washington Navy Yard http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/wny3.html

- ^ Warrington to Paulding, 21 June 1839, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1 June 1839 - 30 June 1839, letter number 77, pp. 1–3, volume 254, RG260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

- ^ Warrington to Paulding, 21 June 1839, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy from Captains ("Captains Letters"), 1 June 1839 - 30 June 1839, letter number 77, pp. 2–3, volume 254, RG260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

- ^ Sharp, John G., A Norfolk Navy Yard Slaveholders Petition to the Secretary of the Navy, June 21, 1839, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/nnysharp6.html accessed 16 September 2021

- ^ Teamoh, 81.

- ^ Teamoh, 84-85.

- ^ Starobin, Robert S. Industrial Slavery in the Old South, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972) 32.

- ^ Christopher Tomlins,In the Matter of Nat Turner A Speculative History(New Jersey:Princeton University Press,2020),164

- ^ Sharp, John G., Station Log Entries for U.S. Navy Yard Gosport 1850, http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/gosportlog.html

- ^ "Captains Letters" Lewis Warrington to the Secretary of the Navy, dated 5 January 1832 NARA M125 RG260 Volume 166, letter number 25