Simon the Zealot (Acts 1:13, Luke 6:15), also the Canaanite or the Canaanean (Matthew 10:4, Mark 3:18; Ancient Greek: Σίμων ὁ Κανανίτης; Coptic: ⲥⲓⲙⲱⲛ ⲡⲓ-ⲕⲁⲛⲁⲛⲉⲟⲥ; Classical Syriac: ܫܡܥܘܢ ܩܢܢܝܐ)[3] was one of the apostles of Jesus. A few pseudepigraphical writings were connected to him, but Jerome does not include him in De viris illustribus written between 392 and 393 AD.[4]

Simon the Zealot | |

|---|---|

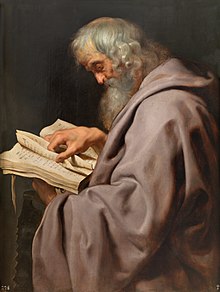

St. Simon, by Peter Paul Rubens (c. 1611), from his Twelve Apostles series at the Museo del Prado, Madrid | |

| Apostle, Preacher, Martyr | |

| Born | 1st century AD Cana, Galilee, Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Died | ~65[1] numerous versions, including Province of Britain, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations that venerate saints |

| Major shrine | relics claimed by many places, including Toulouse; Saint Peter's Basilica[2] |

| Feast | October 28 (Western Christianity) May 10 (Byzantine Christianity) Pashons 15 (Coptic Christianity) ግንቦት 15 (Ethiopian Christianity) July 1 (medieval Hispanic liturgy as attested by sources of the time, such as the Antiphonary of León) |

| Attributes | boat; cross and saw; fish (or two fish); lance; man being sawn in two longitudinally; oar[2] |

| Patronage | curriers; sawyers; tanners[2] |

Identity

editGospel-based traditions

editThe name Simon occurs in all of the Synoptic Gospels and the Book of Acts each time there is a list of apostles, without further details:

Simon, (whom he also named Peter), and Andrew his brother, James and John, Philip and Bartholomew, Matthew and Thomas, James the son of Alphaeus, and Simon called Zelotes, and Judas the brother of James, and Judas Iscariot, which also was the traitor.[5]

To distinguish him from Simon Peter, he is given a surname in all three of the Synoptic Gospels where he is mentioned. Simon is called "Zelotes" in Luke and Acts (Luke 6:15 Acts 1:13). For this reason, it is generally assumed that Simon was a former member of the political party, the Zealots. In Matthew and Mark, however, he is called "Kananites" in the Byzantine majority and "Kananaios" in the Alexandrian manuscripts and the Textus Receptus (Matthew 10:4 Mark 3:18). Both Kananaios and Kananites derive from the Hebrew word קנאי qanai, meaning zealous, so most scholars today generally translate the two words to mean "Zealot". However, Jerome and others, such as Bede, suggested that the word "Kananaios" or "Kananite" should be translated as "Canaanean" or "Canaanite", meaning that Simon was from the town of קנה Cana in Galilee.[6] If this is the case, his epithet would have been "Kanaios".

Robert Eisenman has argued that contemporary talmudic references to Zealots refer to them as kanna'im "but not really as a group—rather as avenging priests in the Temple".[7] Eisenman's broader conclusions, that the zealot element in the original apostle group was disguised and overwritten to make it support the assimilative Pauline Christianity of the Gentiles, are more controversial. John P. Meier argues that the term "Zealot" is a mistranslation and in the context of the Gospels means "zealous" or "religious" (in this case, for keeping the Law of Moses), as the Zealot movement apparently did not exist until 30 to 40 years after the events of the Gospels.[8] However, neither Brandon[9] nor Hengel[10] support this view.

Other identifications

editIn the gospels Simon the Zealot is not directly identified with Simon the brother of Jesus mentioned in Mark 6:3:

"Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?" And they took offense at him.

The Catholic Encyclopedia suggests that Simon the Zealot may be the same person as Simeon of Jerusalem or Simon the brother of Jesus or both. He would then be the cousin of Jesus or a son of Joseph from a previous marriage.[11] Another tradition holds that this is the Simeon of Jerusalem who became the second bishop of Jerusalem, although he was born in Galilee.[12][13]

Later tradition (apocrypha and medieval)

editThe apicriphal second-century Epistle of the Apostles (Epistula Apostolorum),[14] a polemic against gnostics, lists him among the apostles purported to be writing the letter (who include Thomas) as Judas Zelotes. Certain Old Latin translations of the Gospel of Matthew substitute "Judas the Zealot" for Thaddeus/Lebbaeus in Matthew 10:3. To some readers, this suggests that he may be identical with the "Judas not Iscariot" mentioned in John 14:22: "Judas saith unto him, not Iscariot, Our Lord, how is it that thou wilt manifest thyself unto us, and not unto the world?" As it has been suggested that Jude is identical with the Apostle Thomas (see Jude Thomas), an identification of "Simon Zelotes" with Thomas is also possible. Barbara Thiering identified Simon Zelotes with Simon Magus; however, this view has received no serious acceptance. The New Testament records nothing more of Simon, aside from this multitude of possible but unlikely pseudonyms.

In the apocryphal Arabic Infancy Gospel a fact related to this apostle is mentioned. A boy named Simon is bitten by a snake in his hand; he is healed by Jesus, who told the child "you shall be my disciple". The mention ends with the phrase "this is Simon the Cananite, of whom mention is made in the Gospel."[15]

Isidore of Seville drew together the accumulated anecdotes of Simon in De Vita et Morte.

According to the Golden Legend, which is a collection of hagiographies, compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the thirteenth century, "Simon the Cananaean and Judas Thaddeus were brethren of James the Less and sons of Mary Cleophas, who was married to Alpheus."[16][17]

In later tradition, Simon is often associated with Jude the Apostle as an evangelizing team; in Western Christianity, they share their feast day on 28 October. The most widespread tradition is that after evangelizing in Egypt, Simon joined Jude in Persia and Armenia or Beirut in today's Lebanon, where both were martyred in 65. This version is the one found in the Golden Legend. He may have suffered crucifixion as the Bishop of Jerusalem. According to an Eastern tradition, Simon travelled to Georgia on a missionary trip, died in Abkhazia and was buried in Nicopsia, a not yet identified site on the Black Sea coast. His remains were later transferred to Anakopia in today's Abkhazia.[18]

Another tradition states that he traveled in the Middle East and Africa. Christian Ethiopians claim that he was crucified in Samaria, while Justus Lipsius writes that he was sawn in half at Suanir, Persia.[17] However, Moses of Chorene writes that he was martyred at Weriosphora in Caucasian Iberia.[17] Tradition also claims he died peacefully at Edessa.[19][20]

Yet another tradition says he visited Roman Britain. In this account, in his second mission to Britain, he arrived during the year 60, the first of Boadicea's rebellion. He was crucified 10 May 61 by the Roman Catus Decianus, at Caistor, modern-day Lincolnshire in England.[21] According to Caesar Baronius and Hippolytus of Rome, Simon's first arrival in Britain was in the year 44, during the Roman conquest.[21] Nikephoros I of Constantinople writes:

Simon born in Cana of Galilee who for his fervent affection for his Master and great zeal that he showed by all means to the Gospel, was surnamed Zelotes, having received the Holy Ghost from above, travelled through Egypt, and Africa, then through Mauretania and all Libya, preaching the Gospel. And the same doctrine he taught to the Occidental Sea, and the Isles called Britanniae.

Another tradition, doubtless inspired by his title "the Zealot", states that he was involved in the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 AD).[9][10]

Sainthood

editSimon, like the other Apostles, is regarded as a saint by the Catholic Church, including the Eastern Catholic Churches, as also by the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, Lutheran Church and the churches of the Anglican Communion. In the Church of England he is remembered (with Jude) with a Festival on 28 October.[23]

In Christian art

editIn art, Simon has the identifying attribute of a saw because according to tradition he was martyred by being sawn in half.[12]

Gallery

edit-

Simon the Zealot by Caravaggio

-

Statue of Saint Simon (1708-09) by Francesco Moratti in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran

-

Simon Zelotes, 16th-century fresco, eastern wall of the Evangelical church of Leihgestern

-

Statue of Simon the Zealot by Hermann Schievelbein at the roof of the Helsinki Cathedral

-

The Apostle Simon the Zealot by Georg Gsell

-

Saint Simon by James Tissot, Brooklyn Museum

In Islam

editIn Islam, Muslim exegesis and Quran commentary name the twelve apostles and include Simon amongst the disciples. Muslim tradition says that Simon was sent to preach the faith of God to the Berbers, outside North Africa.[24]

References

edit- ^ "St. Simon the Apostle" (in Italian). Blessed Saints and Witnesses. 2005-03-15. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Jones, Terry H (6 January 2009). "Saint Simon the Apostle". Saints.SQPN.com. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Saint Simon". st-takla.org (in Arabic).

- ^ Booth, A.D. (1981). "The Chronology of Jerome's Early Years". Phoenix. 35 (3). Classical Association of Canada: 241. doi:10.2307/1087656. JSTOR 1087656.

This work [De viris illustribus], as he reveals at its start and finish, was completed in the fourteenth year of Theodosius, that is, between 19 January 392 and 18 January 393.

- ^ Luke 6:14–16

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2023-04-01. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Eisenman, Robert (1997). James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Viking Penguin. pp. 33–34.

- ^ Meier, John (2001). A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus Volume 3: Companions and Competitors. Yale University. pp. 132–135. ISBN 978-0-300-14032-3.

- ^ a b Brandon, S.G.F. (1967). Jesus and the Zealots: A Study of the Political Factor in Primitive Christianity. Manchester University Press.

- ^ a b Hengel, M. (1989). The Zealots: Investigations into the Jewish Freedom Movement in the Period from Herod I Until 70 A.D. Translated by Dr David Smith. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-29372-5.

- ^ Bechtel, Florentine Stanislaus (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Löffler, Klemens (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Appendix to the Works of Hippolytus 49.11

- ^ "Epistula Apostolorum". Early Christian Writings. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ The Arabic Gospel of the Infancy of the Saviour.

- ^ de Voragine, Jacobus (1275). The Golden Legend or Lives Of The Saints. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Stracke, Richard. Golden Legend: Life of SS. Simon and Jude. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ McDowell, Sean (2016). The Fate of the Apostles: Examining the Martyrdom Accounts of the Closest Followers of Jesus. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 9781317031895.

- ^ "St. Simon of Zealot". Catholic Online. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "St. Jude Thaddeus and St. Simon the Zealot, Apostles". Catholic News Agency. Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Jowett, G.F. (1961). The Drama of the Lost Disciples. Covenant Publishing Company. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-85205-008-8.

- ^ Cornelius a Lapide, Argumentus Epistoloe St. Pauli di Romanos, ch. 16.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ^ Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brandon M. (2003). Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press (Rowman & Littlefield). p. 86. ISBN 978-0810843059.

Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon

External links

edit- All appearances of "Simon" in the New Testament (mostly referring to Simon Peter)

- Legenda Aurea: Lives of Saints Simon and Jude

- "St. Simon the Apostle" in the Catholic Encyclopedia via newadvent.org

- "Ὁ Ἅγιος Σίμων ὁ Ἀπόστολος ὁ Ζηλωτής". Megas Synaxaristis (in Greek).