The Golden Legend (Latin: Legenda aurea or Legenda sanctorum) is a collection of 153 hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine that was widely read in Europe during the Late Middle Ages. More than a thousand manuscripts of the text have survived.[1] It was probably compiled around 1259 to 1266, although the text was added to over the centuries.[2][3]

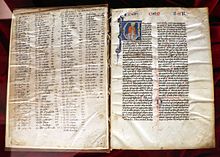

Legenda Aurea, c. 1290, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence | |

| Author | Jacobus de Voragine |

|---|---|

| Original title | Legenda aurea |

| Translator | William Caxton Frederick Startridge Ellis |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | hagiography |

Publication date | 1265 |

| Publication place | Genoa |

Published in English | 1483 |

| Media type | Manuscript |

| OCLC | 821918415 |

| 270.0922 | |

| LC Class | BX4654 .J334 |

Original text | Legenda aurea at Latin Wikisource |

| Translation | Golden Legend at Wikisource |

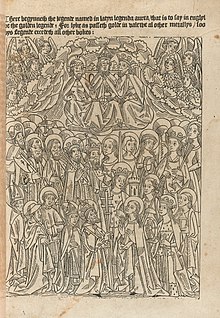

Initially entitled Legenda sanctorum (Readings of the Saints), it gained its popularity under the title by which it is best known. It overtook and eclipsed earlier compilations of abridged legendaria, the Abbreviatio in gestis et miraculis sanctorum attributed to the Dominican chronicler Jean de Mailly and the Epilogus in gestis sanctorum of the Dominican preacher Bartholomew of Trent. When printing was invented in the 1450s, editions appeared quickly, not only in Latin, but also in almost every major European language.[4] Among incunabula, printed before 1501, Legenda aurea was printed in more editions than the Bible[5] and was one of the most widely published books of the Middle Ages.[6] During the height of its popularity the book was so well known that the term "Golden Legend" was sometimes used generally to refer to any collection of stories about the saints.[7] It was one of the first books William Caxton printed in the English language; Caxton's version appeared in 1483 and his translation was reprinted, reaching a ninth edition in 1527.[8]

Written in simple, readable Latin, the book was read in its day for its stories. Each chapter is about a different saint or Christian festival. The book is considered the closest thing to an encyclopaedia of medieval saint lore that survives today; as such, it is invaluable to art historians and medievalists who seek to identify saints depicted in art by their deeds and attributes. Its repetitious nature is explained if Jacobus meant to write a compendium of saintly lore for sermons and preaching, not a work of popular entertainment.

Lives of the saints

editThe book sought to compile traditional lore about saints venerated at the time of its compilation, ordered according to their feast days. Jacobus de Voragine for the most part follows a template for each chapter: etymology of the saint's name, a narrative about their life, a list of miracles performed, and finally a list of citations where the information was found.[9]

Each chapter typically begins with an etymology for the saint's name, "often entirely fanciful".[10] An example (in Caxton's translation) shows his method:

Silvester is said of sile or sol which is light, and of terra the earth, as who saith the light of the earth, that is of the church. Or Silvester is said of silvas and of trahens, that is to say he was drawing wild men and hard unto the faith. Or as it is said in glossario, Silvester is to say green, that is to wit, green in contemplation of heavenly things, and a toiler in labouring himself; he was umbrous or shadowous. That is to say he was cold and refrigate from all concupiscence of the flesh, full of boughs among the trees of heaven.[11]

As a Latin author, Jacobus de Voragine must have known that Silvester, a relatively common Latin name, simply meant "from the forest". The correct derivation is alluded to in the text, but set out in parallel to fanciful ones that lexicographers would consider quite wide of the mark. Even the "correct" explanations (silvas, "forest", and the mention of green boughs) are used as the basis for an allegorical interpretation. Jacobus de Voragine's etymologies had different goals from modern etymologies, and cannot be judged by the same standards. Jacobus' etymologies have parallels in Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae, in which linguistically accurate derivations are set out beside allegorical and figurative explanations.

Jacobus de Voragine then moves on to the saint's life, compiled with reference to the readings from the Roman Catholic Church's liturgy commemorating that saint; then embellishes the biography with supernatural tales of incidents involving the saint's life.

Medieval view of Muhammad

editThe chapter "St Pelagius, Pope and the History of the Lombards" begins with the story of St Pelagius, then proceeds to touch upon events surrounding the origin and history of the Lombards in Europe leading up to the 7th century when the story of Muhammad begins.[12] The story then goes on to describe "Magumeth (Mahomet, Muhammad)" as "a false prophet and sorcerer", detailing his early life and travels as a merchant through his marriage to the widow Khadija, and goes on to suggest that his religious visions came as a result of epileptic seizures and the interventions of a renegade Nestorian monk named Sergius.[13] The chapter conveys the medieval Christian understanding of the beliefs of Saracens and other Muslims. It may be because of this long history that early copies of the entire work were sometimes referred to as Historia Lombardica.[14]

Miracle tales of relics

editMany of the stories also conclude with miracle tales and similar wonderlore from accounts of those who called upon that saint for aid or used the saint's relics. Such a tale is told of Saint Agatha; Jacobus da Varagine has pagans in Catania repairing to the relics of St. Agatha to supernaturally repel an eruption of Mount Etna:

And for to prove that she had prayed for the salvation of the country, at the beginning of February, the year after her martyrdom, there arose a great fire, and came from the mountain toward the city of Catania and burnt the earth and stones, it was so fervent. Then ran the paynims to the sepulchre of S. Agatha and took the cloth that lay upon her tomb, and held it abroad against the fire, and anon on the ninth day after, which was the day of her feast, ceased the fire as soon as it came to the cloth that they brought from her tomb, showing that our Lord kept the city from the said fire by the merits of S. Agatha.[16]

Mary Magdalene's sea voyage

editSources

editJacobus carefully lists many of the sources he used to collect his stories, with more than 120 total sources listed; among the three most important are Historia Ecclesiastica by Eusebius, Tripartite History by Cassiodorus, and Historia scholastica by Petrus Comestor.[18]

However, scholars have also identified other sources which Jacobus did not himself credit. A substantial portion of Jacobus' text was drawn from two epitomes of collected lives of the saints, both also arranged in the order of the liturgical year, written by members of his Dominican order: one is Jean de Mailly's lengthy Abbreviatio in gestis et miraculis sanctorum (Summary of the Deeds and Miracles of the Saints) and the other is Bartholomew of Trent's Epilogum in gesta sanctorum (Afterword on the Deeds of the Saints).[19] The many extended parallels to text found in Vincent de Beauvais' Speculum historiale, the main encyclopedia that was used in the Middle Ages, are attributed by modern scholars to the two authors' common compilation of identical sources, rather than to Jacobus' reading Vincent's encyclopedia.[20] More than 130 more distant sources have been identified for the tales related of the saints in the Golden Legend, few of which have a nucleus in the New Testament itself; these hagiographic sources include apocryphal texts such as the Gospel of Nicodemus, and the histories of Gregory of Tours and John Cassian. Many of his stories have no other known source. A typical example of the sort of story related, also involving St. Silvester, shows the saint receiving miraculous instruction from Saint Peter in a vision that enables him to exorcise a dragon:

In this time it happed that there was at Rome a dragon in a pit, which every day slew with his breath more than three hundred men. Then came the bishops of the idols unto the emperor and said unto him: O thou most holy emperor, sith the time that thou hast received Christian faith the dragon which is in yonder fosse or pit slayeth every day with his breath more than three hundred men. Then sent the emperor for S. Silvester and asked counsel of him of this matter. S. Silvester answered that by the might of God he promised to make him cease of his hurt and blessure of this people. Then S. Silvester put himself to prayer, and S. Peter appeared to him and said: "Go surely to the dragon and the two priests that be with thee take in thy company, and when thou shalt come to him thou shalt say to him in this manner: Our Lord Jesus Christ which was born of the Virgin Mary, crucified, buried and arose, and now sitteth on the right side of the Father, this is he that shall come to deem and judge the living and the dead, I commend thee Sathanas that thou abide him in this place till he come. Then thou shalt bind his mouth with a thread, and seal it with thy seal, wherein is the imprint of the cross. Then thou and the two priests shall come to me whole and safe, and such bread as I shall make ready for you ye shall eat.

Thus as S. Peter had said, S. Silvester did. And when he came to the pit, he descended down one hundred and fifty steps, bearing with him two lanterns, and found the dragon, and said the words that S. Peter had said to him, and bound his mouth with the thread, and sealed it, and after returned, and as he came upward again he met with two enchanters which followed him for to see if he descended, which were almost dead of the stench of the dragon, whom he brought with him whole and sound, which anon were baptized, with a great multitude of people with them. Thus was the city of Rome delivered from double death, that was from the culture and worshiping of false idols, and from the venom of the dragon.[21]

Jacobus describes the story of Saint Margaret of Antioch surviving being swallowed by a dragon as "apocryphal and not to be taken seriously" (trans. Ryan, 1.369).

Perception and legacy

editThe book was highly successful in its time, despite many other similar books that compiled legends of the saints. The reason it stood out against competing saint collections probably is that it offered the average reader the perfect balance of information. For example, compared to Jean de Mailly's work Summary of the Deeds and Miracles of the Saints, which The Golden Legend largely borrowed from, Jacobus added chapters about the major feast days and removed some of the saints' chapters, which might have been more useful to the medieval reader.[22]

Many different versions of the text exist, mostly due to copiers and printers adding additional content to it. Each time a new copy was made, it was common for that institution to add a chapter or two about their own local saints.[23] Today more than 1,000 original manuscripts have been found,[1] the earliest of which dates back to 1265.[24]

Contemporary influences and translations

editThe Golden Legend had a big influence on scholarship and literature of the Middle Ages. According to research by Manfred Görlach, it influenced the South English Legendary, which was still being written when Jacobus' text came out.[25] It was also a major source for John Mirk's Festial, Osbern Bokenam's Legends of Hooly Wummen, and the Scottish Legendary.[26]

By the end of the Middle Ages, The Golden Legend had been translated into almost every major European language.[27] The earliest surviving English translation is from 1438, and is cryptically signed by "a synfulle wrecche".[28] In 1483, the work was re-translated and printed by William Caxton under the name The Golden Legende, and subsequently reprinted many times due to the demand.[29]

16th-century rejection and 20th-century revival

editThe adverse reaction to Legenda aurea under critical scrutiny in the 16th century was led by scholars who reexamined the criteria for judging hagiographic sources and found Legenda aurea wanting; prominent among the humanists were two disciples of Erasmus, Georg Witzel, in the preface to his Hagiologium, and Juan Luis Vives in De disciplinis. Criticism of Jacobus's text was muted within the Dominican Order by the increasing reverence towards him as a Dominican and archbishop, which culminated in his beatification in 1815. The rehabilitation of Legenda aurea in the 20th century, now interpreted as a mirror of the heartfelt pieties of the 13th century, is attributed[30] to Téodor de Wyzewa, whose 1901 retranslation into French, and its preface, have been often reprinted.

Sherry Reames argues[31] that Jacobus' interpretation of his source material emphasized purity, detachment, great erudition and other rarified attributes of the saints; she contrasts this to the same saints as described in de Mailly's Abbreviatio, whose virtues are more relatable, such as charity, humility and trust in God.

Editions and translations

editThe critical edition of the Latin text has been edited by Giovanni Paolo Maggioni (Florence: SISMEL 1998). In 1900, the Caxton version was updated into more modern English by Frederick Startridge Ellis, and published in seven volumes. Jacobus de Voragine's original was translated into French around the same time by Téodor de Wyzewa. A modern English translation of the Golden Legend has been published by William Granger Ryan, ISBN 0-691-00153-7 and ISBN 0-691-00154-5 (2 volumes).

A modern translation of the Golden Legend is available from Fordham University's Medieval Sourcebook.[32]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Hilary Maddocks, "Pictures for aristocrats: the manuscripts of the Légende dorée", in Margaret M. Manion, Bernard James Muir, eds. Medieval texts and images: studies of manuscripts from the Middle Ages 1991:2; a study of the systemization of the Latin manuscripts of the Legenda aurea is B. Fleith, "Le classement des quelque 1000 manuscrits de la Legenda aurea latine en vue de l'éstablissement d'une histoire de la tradition" in Brenda Dunn-Lardeau, ed. Legenda Aurea: sept siècles de diffusion, 1986:19–24

- ^ An introduction to the Legenda, its great popular late medieval success and the collapse of its reputation in the 16th century, is Sherry L. Reames, The Legenda Aurea: a reexamination of its paradoxical history, University of Wisconsin, 1985.

- ^ Hamer 1998:x

- ^ Hamer 1998:xx

- ^ Reames 1985:4

- ^ Hamer 1998:ix

- ^ Hamer 1998:xvii

- ^ Jacobus (de Vorágine) (1973). The Golden Legend. CUP Archive. pp. 8–. GGKEY:DE1HSY5K6AF. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Hamer 1998:x

- ^ Hamer 1998:xi

- ^ "The Life of St. Sylvester." Archived 25 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine. Trans. William Caxton. Ed. F. S. Ellis. Reproduced at www.Aug.edu/augusta/iconography/goldenLegend, Augusta State University.

- ^ Voragine, Jacobus De (11 April 2018). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691154077. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Voragine, Jacobus De (11 April 2018). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691154077. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hamer 1998:x

- ^ "Heiligenlevens in het Middelnederlands[manuscript]". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "The Life of St. Agatha." Archived 1 August 2012 at archive.today The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine. Trans. William Caxton. Ed. F. S. Ellis. London: Temple Classics, 1900. Reproduced at www.Aug.edu/augusta/iconography/goldenLegend, Augusta State University.

- ^ "St Barbara Directing the Construction of a Third Window in Her Tower". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Hamer 1998:xii

- ^ Hilary Maddocks, "Pictures for aristocrats: the manuscripts of the Légende dorée", in Margaret M. Manion and Bernard James Muir, eds.,Medieval Texts and Images: studies of manuscripts from the Middle Ages 1991:2 note 4.

- ^ Christopher Stace, tr., The Golden Legend: selections (Penguin), "Introduction" pp. xii–xvi, reporting conclusions of K. Ernest Geith, (Geith, "Jacques de Varagine, auteur indépendant ou compilateur?" in Brenda Dunn-Lardeau, ed. Legenda aurea – 'La Légende dorée 1993:17–32) who printed the comparable texts side by side.

- ^ "The Life of St. Sylvester." Archived 25 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine. Trans. William Caxton. Ed. F. S. Ellis. London: Temple Classics, 1900. Reproduced at www.Aug.edu/augusta/iconography/goldenLegend, Augusta State University.

- ^ Hamer 1998:xvi

- ^ Hamer 1998:xx

- ^ Hamer 1998:xx

- ^ Hamer 1998:xxi

- ^ Hamer 1998:xxi–xxii

- ^ Hamer 1998:xx

- ^ Hamer 1998:xxii

- ^ Hamer 1998:xxii-xxiii

- ^ Reames 1985:18–

- ^ Reaves, 1985, pp 197-

- ^ The Golden Legend. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine. Trans. William Caxton. Ed. F. S. Ellis. London: Temple Classics, 1900. Reproduced in Medieval Sourcebook, Fordham University: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/index.asp

Works cited

edit- Hamer, Richard (1998). "Introduction". The Golden Legend: Selections. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140446486.

- Reames, Sherry L. (1985). The Legenda Aurea: A Reexamination of Its Paradoxical History. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299101509 – via GoogleBooks.

External links

edit- Works related to The Golden Legend at Wikisource, William Caxton's text with missing page from St. Paul supplied.

- Golden Legend at Hathi Trust

- The Golden Legend—William Caxton's Middle English version (not quite complete).

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Illustrations of The Golden Legend from the HM 3027 manuscript of Legenda Aurea from the Huntington Library (Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine)

- William Caxton's version (complete)