Sifting and winnowing is a metaphor for the academic pursuit of truth affiliated with the University of Wisconsin–Madison. It was coined by UW President Charles Kendall Adams in an 1894 final report from a committee exonerating economics professor Richard T. Ely of censurable charges from state education superintendent Oliver Elwin Wells. The phrase became a local byword for the tenet of academic freedom.

History

editIn the 1890s, University of Wisconsin economics professor Richard T. Ely's philosophy and radical practice came under fire from state education superintendent Oliver Elwin Wells.[1] Ely was known to be liberal and pro-union, having published a book on socialism.[1] Wells protested Ely's beliefs, teaching, and rhetoric, but UW president Charles Kendall Adams and the Board of Regents did not censure Ely.[1] A committee appointed to address the charges produced a report that exonerated Ely upon acceptance by the regents.[1] The report introduced the idea of "sifting and winnowing":[1]

As Regents of a university with over a hundred instructors supported by nearly two millions of people who hold a vast diversity of views regarding the great questions which at present agitate the human mind, we could not for a moment think of recommending the dismissal or even the criticism of a teacher even if some of his opinions should, in some quarters, be regarded as visionary. Such a course would be equivalent to saying that no professor should teach anything which is not accepted by everybody as true. This would cut our curriculum down to very small proportions. We cannot for a moment believe that knowledge has reached its final goal, or that the present condition of society is perfect. We must therefore welcome from our teachers such discussions as shall suggest the means and prepare the way by which knowledge may be extended, present evils be removed and others prevented. We feel that we would be unworthy of the position we hold if we did not believe in progress in all departments of knowledge. In all lines of academic investigation it is of the utmost importance that the investigator should be absolutely free to follow the indications of truth wherever they may lead. Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere we believe the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.

— 1894 Ely trial committee final report, via Herfurth's Sifting and Winnowing[2]

Ely later referred to the report as the "Wisconsin Magna Charta" for its guarantees of academic freedom in pursuit of truth.[3] In Decades of Chaos and Revolution, Stephen J. Nelson contends that UW's sentiment on academic freedom had been set "well before" the 1890s.[1] He added that the 1894 statement "sounds the trumpet of the fundamental principles of the academy: an unending, unlimited belief in the creed of academic freedom and inquiry."[1] Ely's hearing was later dramatized in a 1964 television episode of Profiles in Courage, featuring actors Dan O'Herlihy, Edward Asner, and Leonard Nimoy.[4]

The "sifting and winnowing" construction was coined by Adams, the UW president, who had defended Ely publicly and read his book.[3] It was later invoked by UW–Madison Chancellor Robben Wright Fleming when responding to protestors during his tenure.[5]

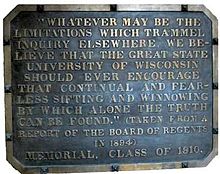

In a later incident, sociology professor Edward Alsworth Ross was censured upon inviting anarchist Emma Goldman to address his class.[6] He did not share her beliefs, but supported her free speech.[6] In memorial of the incident, the Class of 1910 created a commemorative "sifting and winnowing" plaque of the phrase in its context, which the regents rejected.[6] After the Class appealed to area newspapers, the regents relented.[6] The plaque was installed on Bascom Hall in 1915, where it remains.[6] It was rededicated in 1957.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Nelson 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Herfurth 1949, ch. 1.

- ^ a b Nelson 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Hansen 1998, p. 328.

- ^ Nelson 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f "Letters & Science 101 - Traditions: Sifting and Winnowing". University of Wisconsin–Madison College of Letters and Science. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

Bibliography

edit- Curti, Merle Eugene; Carstensen, Vernon Rosco; Cronon, Edmund David; Jenkins, John William (1949). The University of Wisconsin: 1848-1925. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-80572-2.

- Downs, Donald Alexander (October 16, 2006). Restoring Free Speech and Liberty on Campus. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68971-7.

- Grant, Carl A. (1975). Sifting and winnowing: an exploration of the relationship between multi-cultural education and CBTE. Teacher Corps Associates, Univ. of Wisconsin.

- Hansen, W. Lee (1998). Academic Freedom on Trial: 100 Years of Sifting and Winnowing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Madison: Office of University Pub., University of Wisconsin-Madison. ISBN 978-0-9658834-1-2.

- Herfurth, Theodore (1949). Sifting and Winnowing: A Chapter in the History of Academic Freedom at the University of Wisconsin. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- Nelson, Stephen J. (2012). Decades of Chaos and Revolution: Showdowns for College Presidents. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-1082-0.